Acts of Union 1800 Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the Acts of Union 1800 to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Personal union of England and Ireland

- Anglo-Irish relations in the 17th and 18th centuries

- Union of Great Britain and Ireland

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about the Acts of Union 1800!

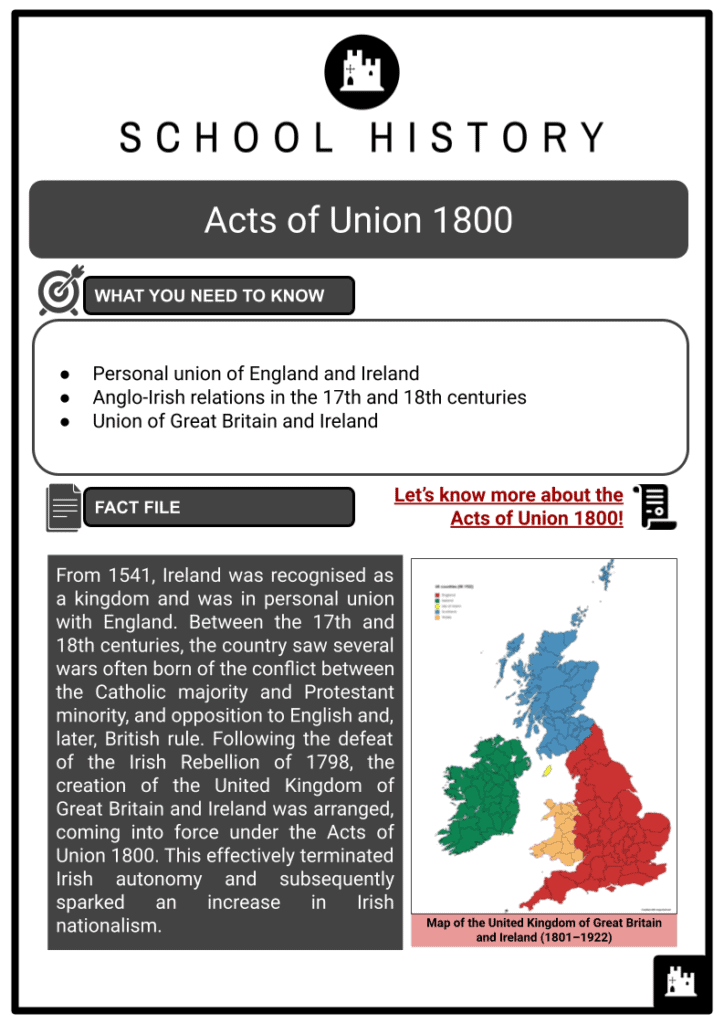

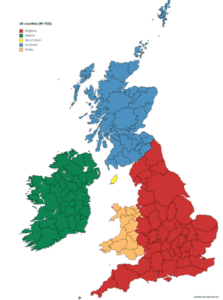

From 1541, Ireland was recognised as a kingdom and was in personal union with England. Between the 17th and 18th centuries, the country saw several wars often born of the conflict between the Catholic majority and Protestant minority, and opposition to English and, later, British rule. Following the defeat of the Irish Rebellion of 1798, the creation of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was arranged, coming into force under the Acts of Union 1800. This effectively terminated Irish autonomy and subsequently sparked an increase in Irish nationalism.

Personal union of England and Ireland

- The Norman invasion of Ireland in the 12th century led to a partial conquest of the island and signalled the beginning of more than 800 years of English political and military involvement in Ireland. This meant that the monarch of England was the overlord of the Lordship of Ireland.

- In the succeeding years, a Gaelic resurgence over most of the country emerged.

- By the end of the 15th century, the English Crown did not pursue the conquest of the island until after the end of the Wars of the Roses.

- During this period, central English authority in Ireland had all but gone.

- With Henry VIII of England’s desire to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, he broke with Rome and declared himself as head of the Church in England, a process that was completed in 1534.

- Two years later, the Irish Parliament in Dublin declared Henry VIII the head of the Church of Ireland and a royal commission ordered the shutting of Irish monasteries. This caused discontent among the Anglo-Irish and the Gaelic Irish alike.

- From 1536, the English King set about imposing a military solution in response to the resistance of the Irish people.

- Having put down this rebellion, he resolved to reconquer Ireland and bring it under Crown control so the island would not become a base for future rebellions or foreign invasions of England.

- In 1541, the status of Ireland was upgraded from a lordship to a full kingdom with the passage of the Crown of Ireland Act 1542 by the Irish Parliament.

- The act established the personal union of England and Ireland, as well as Henry VIII and his heirs and successors as kings of Ireland.

- The act aimed to restore the central English authority that had been lost in the previous centuries.

- The creation of the Kingdom of Ireland was to transform the character of the relationship that existed between Ireland and England.

A portrait of Henry VIII of England - Under the policy of surrender and regrant, Gaelic leadership assimilated into the new structure of the government of the Kingdom of Ireland and the Church of England under Henry VIII.

- English law, culture, language and religion were imposed on Ireland.

- The English Reformation, however, failed to take hold in most of the country and had no significant influence on the Irish Parliament.

- Various English administrations either negotiated or fought with the independent Irish and Old English lords.

- The Tudor conquest of Ireland was completed during the reign of Elizabeth I in 1603 with the surrender of the Irish earls and tolerance of, if not submission to, Protestantism on the island.

- After this point, the English authorities in Dublin instituted a centralised government to the entire island and successfully disarmed the native lordships.

- However, the English were not successful in converting the Catholic Irish to the Protestant religion.

- On the contrary, English rule was further resented in the country due to the harsh methods used by the Crown authority to bring Ireland under English control.

Anglo-Irish relations in the 17th and 18th centuries

- From 1603, the dispossession of large holdings belonging to several hundred native Catholic nobility and other landowners in the country continued. The introduction of Protestant settlers from England and Scotland also emerged from 1609. The desire of Catholic landowners to recover lost estates thus contributed heavily to the outbreak of war in the early 1640s.

- The Irish Confederate Wars took place in Ireland between 1641 and 1653 and were fought over governance, land ownership, religious freedom and religious discrimination.

- The main issues of the conflict were whether Irish Catholics or British Protestants possessed most political power and owned most of the land, and whether Ireland would be a self-governing kingdom under Charles I or subordinate to the Parliament in England.

- When the war concluded, Ireland was occupied and annexed by the English Commonwealth.

- The repression of Catholicism continued and most Catholic-owned land was confiscated.

- Moreover, tens of thousands of Irish rebels were sent to the Caribbean or Virginia as indentured servants or joined Catholic armies in Europe.

- The year 1689 saw the outbreak of another conflict known as the Williamite War in Ireland.

- Fought between the supporters of the deposed English Catholic monarch, James II, and the supporters of his Protestant successor, William III, the Protestant forces defeated the Catholic resistance at Boyne (1690) and Aughrim (1691).

A depiction of the Battle of the Boyne (1690) between James II and William III - This marked the beginning of the so-called Protestant Ascendancy.

- Much Irish land was confiscated by the Crown from the Catholic aristocrats and then sold to people who were considered loyal, most of whom were English and Protestant.

- As a result, a minority of landowners, Protestant clergy, members of the professions, and all members of the Anglican Church became the new ruling class in the country.

- The process of Protestant Ascendancy was facilitated by the passing of various Penal Laws, which discriminated against Catholics in religion, education and politics.

- In 1707, the Acts of Union were passed, uniting England and Scotland by the name of Great Britain. This meant that the Irish Parliament was now subordinate to the Parliament of Great Britain.

- The last quarter of the 18th century saw a transformation in Irish society and politics as the English attitudes towards Catholicism relaxed.

- Irish Catholics were granted some property rights, the right to vote in elections provided they owned property, and a measure of political participation.

- In 1782–83, Ireland gained effective legislative independence from Great Britain through the Constitution of 1782.

- In accordance with the Constitution of 1782, Great Britain renounced all rights to legislate for Ireland, and declared that no appeal from the decision of any court in Ireland could be heard in any court in Great Britain.

- Global events such as the American and French Revolutions inspired the formation of an indigenous nationalist movement in Ireland.

- A major uprising against British rule, known as the Irish Rebellion of 1798, broke out.

- The rebellion had initial successes but was ultimately crushed by the government. Moreover, it jeopardised the constitutional arrangements that were established in 1782–83.

Union of Great Britain and Ireland

- Following the suppression of the armed rebellion against British rule in Ireland, Irish nationalists started to consider other paths to self-government. Anglo-Irish leaders also felt threatened that political instability and rising nationalism might result in a Catholic-dominated Irish Parliament. Meanwhile, the British government became increasingly concerned over the state of constitutional relations between Great Britain and Ireland, and began to examine how a union might be made to work.

- In early 1799, the initial proposals for the parliamentary union of Great Britain and Ireland were discussed in Dublin and received heavy opposition in the Irish Commons.

- The bill was thus delayed to the succeeding session.

- Meanwhile, at Westminster, the British cabinet during the first Pitt ministry also proposed a merger of the kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland and their parliaments.

- The British elites thought that the proposed union was desirable as it would reduce the threat of Ireland breaking away from Britain and forming an alliance with the French.

- Negotiations and parliamentary proceedings at Westminster and in Dublin finally resulted in an agreement on a legislative union.

A portrait of George III - This was achieved by an enormous programme of persuasion, where significant bribery and corruption were deployed.

- Passed in 1800 and entered into force on 1 January 1801, the Acts of Union comprised of:

- Union with Ireland Act 1800. An Act of the Parliament of Great Britain, passed on 2 July 1800

- Act of Union (Ireland) 1800. An Act of the Parliament of Ireland, passed on 1 August 1800

Articles of the Acts of Union 1800

The Parliaments of England and Ireland agreed upon the following articles:

- That Great Britain and Ireland shall upon 1 January 1801 be united into one kingdom; and that the titles appertaining to the Crown shall be such as his Majesty shall be pleased to appoint.

- That the succession to the Crown shall continue limited and settled as at present.

- That the United Kingdom be represented in one Parliament.

- That such Act as shall be passed in Ireland to regulate the mode of summoning and returning the lords and commoners to serve in the united Parliament of the United Kingdom shall be considered as part of the treaty of union.

- The churches of England and Ireland to be united into one Protestant Episcopal Church, and the doctrine of the Church of Scotland to remain as now established.

- The subjects of Great Britain and Ireland shall be on the same footing in respect of trade and navigation, and in all treaties with foreign powers the subjects of Ireland shall have the same privileges as the British subjects.

- That Ireland would have to contribute two-seventeenths towards the expenditure of the United Kingdom.

- All laws in force at the union, and all courts of jurisdiction within the respective kingdoms, shall remain, subject to such alterations as may appear proper to the united Parliament.

- Under the ensuing legislation, the Irish Members of Parliament and peers joined the 18th Parliament of Great Britain, in what now became the first parliament of the United Kingdom held on 22 January 1801.

- As a consequence of the union, the Union Flag was created, combining the flags of the St George’s Cross and the St Andrew’s Saltire of Scotland with the St Patrick’s Saltire to represent Ireland.

- At the same time, the fleur-de-lis were removed from the Royal Standard of the United Kingdom as the weakening English claims to the French throne were soon abandoned.

- Prime Minister Pitt intended to follow the acts with more far-reaching reforms such as the Catholic emancipation, which he viewed as an essential element of the union.

- This attempt was thwarted by George III, who apparently had no inkling of Pitt’s plan.

- These differences between the King and the prime minister ended in the resignation of Pitt in March 1801.

- The abolition of the Irish Parliament effectively ended Irish autonomy and was followed by economic decline in Ireland as members of the ruling class emigrated to the new centre of power in London. The Acts of Union also fuelled another increase in Irish nationalism and provoked a campaign for Catholic emancipation in the succeeding decades.

Image Sources

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d4/United_Kingdom_of_Great_Britain_and_Ireland.png/446px-United_Kingdom_of_Great_Britain_and_Ireland.png?20210330055316

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f9/After_Hans_Holbein_the_Younger_-_Portrait_of_Henry_VIII_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg/800px-After_Hans_Holbein_the_Younger_-_Portrait_of_Henry_VIII_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/83/Jan_van_Huchtenburg_-_De_slag_aan_de_Boyne.jpg/1024px-Jan_van_Huchtenburg_-_De_slag_aan_de_Boyne.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f2/King_George_III_of_England_by_Johann_Zoffany.jpg/800px-King_George_III_of_England_by_Johann_Zoffany.jpg