Download the Agricultural Revolution Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the Agricultural Revolution to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Table of Contents

Add a header to begin generating the table of contents

Summary

- Crop Rotation

- Mechanisation

- The Enclosure

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about the Agricultural Revolution!

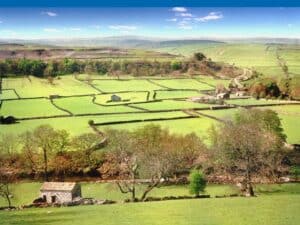

- The agricultural revolution, which began in Britain in the 18th century, was a progressive modification of the conventional agricultural system. The reallocation of land ownership to make farms more compact and increased investment in technical improvements, such as new machinery, better drainage, scientific breeding methods and experimentation with new crops and crop rotation systems, were all part of this complex transformation, which took until the 19th century to complete.

CROP ROTATION

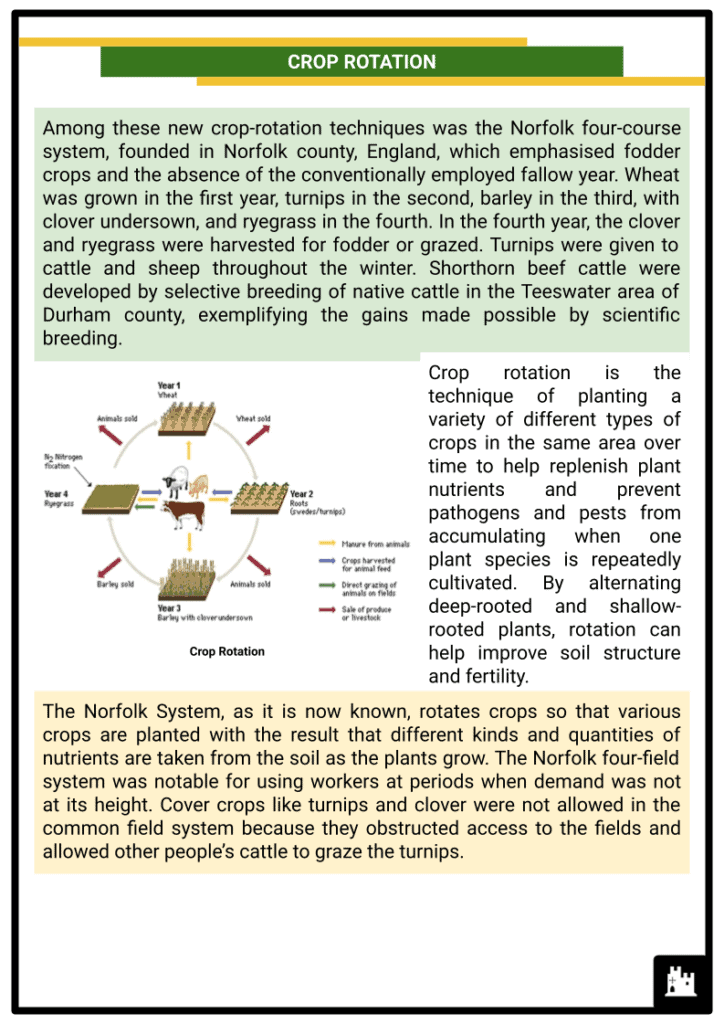

- Among these new crop-rotation techniques was the Norfolk four-course system, founded in Norfolk county, England, which emphasised fodder crops and the absence of the conventionally employed fallow year. Wheat was grown in the first year, turnips in the second, barley in the third, with clover undersown, and ryegrass in the fourth. In the fourth year, the clover and ryegrass were harvested for fodder or grazed. Turnips were given to cattle and sheep throughout the winter. Shorthorn beef cattle were developed by selective breeding of native cattle in the Teeswater area of Durham county, exemplifying the gains made possible by scientific breeding.

- Crop rotation is the technique of planting a variety of different types of crops in the same area over time to help replenish plant nutrients and prevent pathogens and pests from accumulating when one plant species is repeatedly cultivated. By alternating deep-rooted and shallow-rooted plants, rotation can help improve soil structure and fertility.

- The Norfolk System, as it is now known, rotates crops so that various crops are planted with the result that different kinds and quantities of nutrients are taken from the soil as the plants grow. The Norfolk four-field system was notable for using workers at periods when demand was not at its height. Cover crops like turnips and clover were not allowed in the common field system because they obstructed access to the fields and allowed other people’s cattle to graze the turnips.

- During the Middle Ages, the open field system featured a two-field crop rotation system, with one field being left fallow or turned into pasture for a period of time in order to recover part of the plant nutrients. Later, a three-year three-field crop rotation cycle was used, with a different crop in each of two fields (e.g., oats, rye, wheat and barley), a legume like peas or beans in the second field, and the third field fallow.

- In a three-crop rotation system, 10-30% of the arable land is usually fallow. About every year, each field was planted with a different crop. Over the next two centuries, consistent planting of legumes like peas and beans in previously fallow areas gradually restored the fertility of certain croplands.

- The capability of bacteria on legume roots to fix nitrogen from the air into the soil in a form that plants could use helped to improve plant growth in the empty field.

- Flax and mustard family members were other crops that were planted on occasion.

- Convertible husbandry, or the technique of switching a field from pasture to grain, incorporated grassland into the rotation.

- Ploughing grassland and planting cereals resulted in good yields for a few years because nitrogen builds up slowly in pasture.

- Convertible husbandry, on the other hand, had a significant disadvantage in terms of the amount of effort required to break up pastures and the difficulty in building them.

- Farmers in Flanders (parts of France and modern-day Belgium) developed a more efficient four-field crop rotation system, replacing the three-year crop rotation fallow year with turnips and clover (a legume) as forage crops. Farmers were able to recover soil fertility and some of the plant nutrients that had been lost due to crop rotation using the four-field rotation approach.

- Turnips first appear in English probate documents in 1638, although they were not frequently utilised until around 1750.

- Before turnips and clover were widely planted, fallow land made up around 20% of England's arable land in 1700.

MECHANISATION

- Since the introduction of guano and nitrates from South America in the mid-19th century, fallow has progressively diminished, reaching just approximately 4% in 1900.

- Wheat, barley, turnips and clover, in that sequence, would be grown in each field in subsequent years.

- Turnips were a good feed crop, as ruminant animals could consume their tops and roots for most of the summer and winter.

- Clover would return nitrates (nitrogen-containing salts) to the soil, therefore there was no need to leave the soil fallow.

- When ploughed under after one or two years, the clover formed excellent pasture and hay fields, as well as green manure.

- Clover and turnips allowed more animals to be retained through the winter, resulting in more milk, cheese, meat and manure, all of which helped to preserve soil fertility.

- The discovery of new, and improvement of existing equipment, such as the plough, seed drill and threshing machine, were major factors in the Agricultural Revolution, since they improved the efficiency of agricultural operations. The Agricultural Revolution was characterised by the mechanisation and rationalisation of agriculture. To increase the efficiency of various agricultural processes, new tools were devised and existing ones were refined.

- For a millennium, the basic plough with coulter, ploughshare and mouldboard remained in use. Major design modifications did not become frequent until the Age of Enlightenment, when technology advanced rapidly. In the early 17th century, the Dutch bought an iron-tipped, curved mouldboard, adjustable depth plough from the Chinese. It could be drawn by one or two oxen instead of the six or eight that the heavy-wheeled northern European plough required.

- In 1701, Jethro Tull improved it further in England. Prior to the invention of the seed drill, most seeds were planted by manually disseminating (evenly throwing) them across the prepared soil and then lightly harrowing the earth to cover the seed. Birds, insects and mice ate seeds that were left on the ground. Seeds were sown too close together and too far apart due to a lack of control over spacing. Alternatively, seeds might be planted one at a time with a hoe and/or a shovel.

- Cutting down on wasted seed was important because the yield of seeds harvested to seeds planted at that time was only around four or five.

- Tull’s drill was a mechanical seeder that effectively sowed at the proper depth and spacing, then covered the seed to allow it to flourish.

- Seed drills of this and subsequent sorts, on the other hand, were both costly and unreliable, as well as delicate.

- They were not widely used in Europe until the mid-19th century.

- Many early drills were small enough to be hauled by a single horse and were in use well into the 1930s.

- Tull recalled how disagreement with his servants prompted him to design the seed drill in his 1731 publication.

- He fought to impose his new ideas on them, partly because they resented the danger to their jobs as workers and ploughing skills.

- Around 1733, he also devised apparatus to help him carry out his drill husbandry technique.

- His first innovation was a drill plough for sowing wheat and turnip seed three rows at a time in drills.

- A threshing machine, also known as a thresher, is a piece of farm equipment that threshes grain by pounding the plant to make the seeds fall out of the stalks and husks. Threshing was done by hand with flails before such devices were created, and it was exceedingly hard and time-consuming, accounting for nearly a quarter of agricultural work by the 18th century. Farm work was relieved of a significant amount of drudgery when this procedure was mechanised.

- Andrew Meikle, a Scottish engineer, created the first threshing machine in 1786, and the following adoption of similar devices was one of the earliest examples of agricultural mechanisation.

THE ENCLOSURE

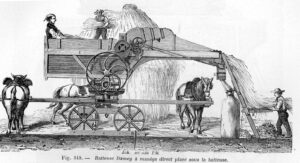

- Enclosure, or the practice of ending customary rights on common land previously held in the open field system and restricting land usage to the owner, was one of the causes of the Agricultural Revolution and a major factor in labour migration from rural areas to increasingly industrialised cities. Enclosure took away the majority of England's medieval common land.

- Enclosure or inclosure was a process in English social and economic history that abolished customary privileges such as mowing meadows for hay or grazing livestock on common land that was formerly held in the open field system.

- These uses of the property were prohibited to the owner once it was fenced, and the land was declared to be for the use of commoners.

- In England and Wales, the phrase also refers to the process that brought an end to the old practice of open-field arable farming.

- Such land was walled (enclosed) and deeded or claimed to one or more owners under enclosure.

- During the 16th century, the process of enclosure became a common aspect of the English agricultural landscape.

- Unenclosed commons were primarily limited to extensive stretches of harsh pasture in mountainous regions and relatively tiny residual pieces of land in the lowlands by the 19th century.

- Enclosure was accomplished by purchasing the ground rights and all common rights in order to obtain exclusive rights of use, increasing the value of the property. Another technique was to pass laws that caused or forced enclosure, such as parliamentary enclosure. Enclosure was occasionally accompanied by force, opposition and violence, and it is still one of the most controversial aspects of English agricultural and economic history.

- Large landowners benefited mostly from a gain in the value of their own land, rather than from expropriation.

- After the enclosure, smaller landowners may be able to sell their property to larger landowners for a better price.

- Protests against parliamentary enclosures persisted, sometimes in Parliament, often in the afflicted communities, and occasionally as organised mass revolts.

- Enclosed land was worth twice as much, a price supported by its greater production.

- While many villagers were given plots in the newly enclosed manor, this compensation was not necessarily enough to cover the expenses of enclosure and fencing for small landowners.

- Many historians believe that enclosure had a significant role in the decline of small landholders in England compared to the Continent, however others believe the trend began earlier.

- The consequences of enclosure on the household economies of smallholders and landless labourers sparked widespread opposition. Common rights previously included grazing rights for geese, foraging for pigs, gleaning, berrying and fuel collecting, in addition to cattle and sheep grazing. Agriculture employment did not decline throughout the time of legislative enclosures, but it did not keep pace with the expanding population. As a result, significant numbers of people moved from rural regions to cities, where they were employed as workers throughout the Industrial Revolution.

- The farmer had control over enclosed land and was able to use improved farming methods. In contemporaneous sources, there was universal consensus that enclosed property provided higher profit potential. Crop yields and livestock output grew after enclosure, while productivity improved to the point where there was a labour surplus. One of the things that aided the Industrial Revolution was the expanded labour supply.A