Download Charles I Worksheets

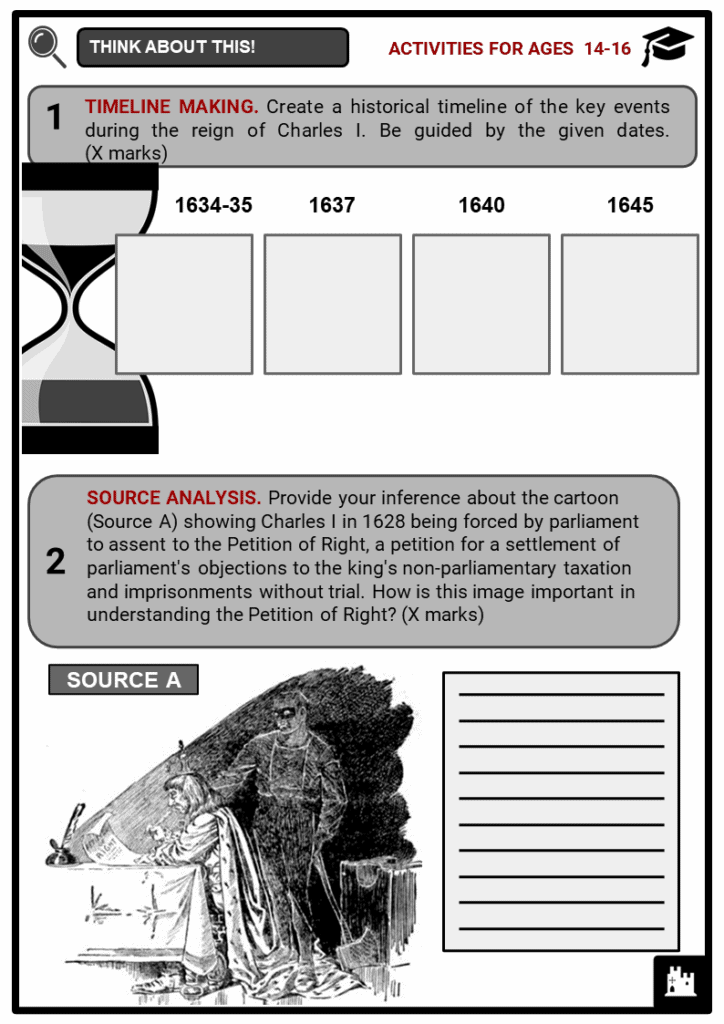

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach Charles I to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Table of Contents

Add a header to begin generating the table of contents

Summary

- Ascension of Charles I to the throne

- Foreign, fiscal, and religious policies under the rule of Charles I

- Problems encountered by Charles I with Parliament

- Summary of the English Civil War

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about Charles I

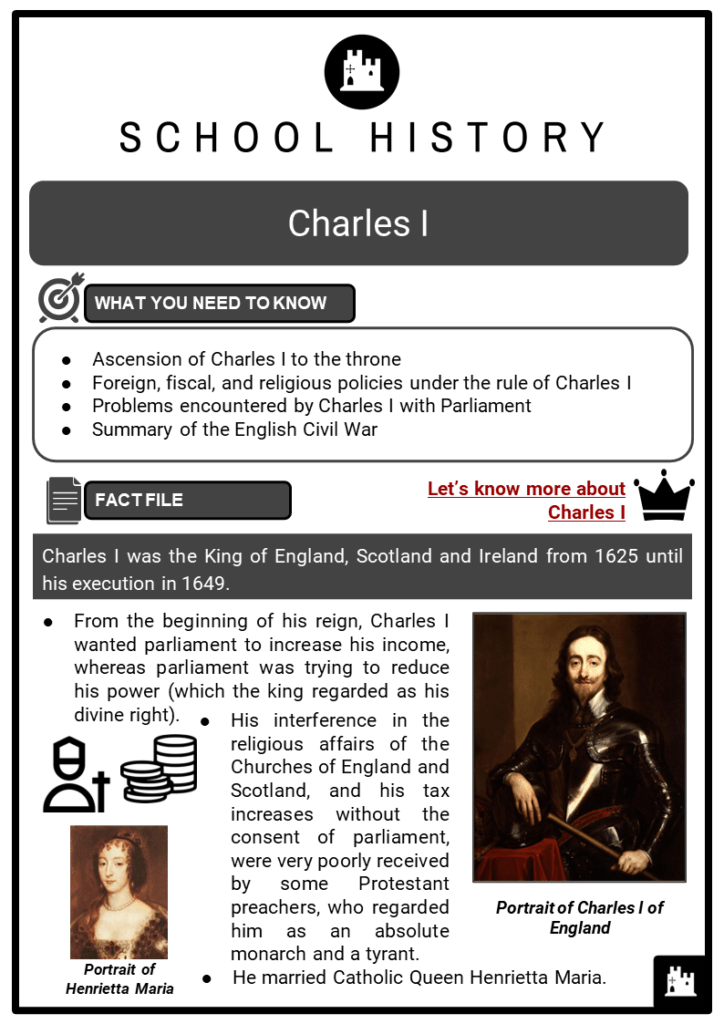

- Charles I was the King of England, Scotland and Ireland from 1625 until his execution in 1649.

- From the beginning of his reign, Charles I wanted parliament to increase his income, whereas parliament was trying to reduce his power (which the king regarded as his divine right).

- His interference in the religious affairs of the Churches of England and Scotland, and his tax increases without the consent of parliament, were very poorly received by some Protestant preachers, who regarded him as an absolute monarch and a tyrant.

- He married Catholic Queen Henrietta Maria.

Key Facts

- Charles I was also associated with controversial ecclesiastical figures, such as Richard Montagu and William Laud, whom he named Archbishop of Canterbury.

- Many subjects, including the Puritans, considered actions like these as bringing the Church of England too close to the Catholic Church.

- His attempts to impose religious reforms on Scotland strengthened the position of the English and Scottish Parliaments and precipitated the fall of the king.

Infancy and Youth

- Charles was the second son of James I Stuart and Anne of Denmark. He was born on November 19, 1600.

- Weak and sickly, at the age of three he was still unable to speak. When, after the death of Elizabeth I, James became King of England, the child was initially left in Scotland because of his health, and reached England only the following year. When he was entrusted to the care of Lady Carey and Lord Fyvie, he learned to walk and to talk. Nonetheless, he retained a certain hesitation in oral expression throughout his life.

- Unlike his older brother Henry, Prince of Wales, Charles was not well regarded, because of his rickets. He adored Henry and tried to emulate him. In 1605, he was named Duke of York. That same year, he was included as a knight in the Order of Bath and was entrusted to the tutelage of Scottish Presbyterian Thomas Murray, with whom Charles was able to deepen his knowledge of classical letters, languages, mathematics and religion.

- 1611 - He obtained the title of Knight of the Order of the Garter.

- 1612 - At the beginning of November 1612, his elder brother died of typhoid fever.

- Charles, who had turned twelve just two weeks earlier, suddenly became Crown Prince, assuming the title of Prince of Wales.

- 1616 - Charles became Count of Chester in November 1616.

The Prince of Wales’ ascension to the throne

- When his sister Elizabeth married Frederick V and moved to Heidelberg, Charles remained the only heir to the throne of England.

- The young prince was profoundly influenced by George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham, his father’s favourite courtier, who took Charles to Spain with him in 1623.

- Villiers was trying to arrange a marriage between Charles and the Infanta Maria Anna, daughter of King Philip III of Habsburg, with the intention of restoring peace to the continent.

- The mission ended in a stalemate, since the Spaniards, pressured by Pope Urban VIII, required the Prince of Wales to convert to Catholicism before asking for the infanta’s hand.

- Furthermore, a personal dispute erupted between the Duke of Buckingham and the Count of Olivares, the Spanish Prime Minister. Following their return from Spain, both Charles (although reluctant) and the Duke of Buckingham asked James I to declare war on Spain.

- With the encouragement of his Protestant advisers, James summoned parliament to request funding for the war and to obtain the approval for the marriage between Charles and Henrietta Maria of France, sister of King Louis XIII.

- Parliament voted on these decisions but expressed much criticism of the previous attempt to forge a marriage alliance with Spain. James was growing old, and controlling parliament proved particularly difficult. During the last year of his father’s life, Charles and the Duke of Buckingham held power.

Ascension to the throne and marriage with Henrietta Maria

- Charles ascended to the throne in March 1625, and on May 1 of the same year, he married Henrietta Maria by proxy. She was nine years his junior.

- Parliament was not in favour of his marriage to a Catholic princess since they feared that Charles would eliminate the severe limitations that Catholics were subjected to, and undermine Protestant power in the country.

- Although he had promised parliament that he would not mitigate the restrictive laws against Catholics, Charles had promised the exact opposite to the King of France in the secret marriage agreement.

- The couple married on June 13, 1625, in Canterbury, and Charles was crowned by Archbishop George Abbot on February 2, 1626, without the presence of his wife. The couple had nine children, of whom only three males and three females survived infancy.

Foreign Policy

- Charles’ main concern during his early years of government was foreign policy. His sister’s husband, Frederick V Wittelsbach, one of the protagonists of the first phase of the Thirty Years’ War, had lost his possession of Bohemia and the Palatinate.

- Frederick V Wittelsbach expected Charles to help him in a war against Spain. Charles announced to parliament that England would liberate the Palatinate by entering the war.

- In order to finance the war on the mainland, the king commissioned Buckingham, who had the title of Lord of the Admiralty, to intercept and capture Spanish ships laden with gold from the Indies.

- The House of Commons granted the king a substantial loan of £140,000. Moreover, the House of Commons granted the king the collection of some important taxes for one year.

- In such a way, the House of Commons hoped to be able to control Charles’ power by forcing him to renew the concession every year. Charles’ supporters in the House of Lords, led by Buckingham, refused to approve the provision, and so, although no official concession had been given to him, Charles continued to collect taxes.

- The war against Spain had a negative outcome due to the Duke of Buckingham’s lack of experience in conducting military operations. Despite parliament’s protests, Charles refused to expel his adviser and friend. Soon, the king provoked a new controversy by imposing a ‘forced loan’ without parliamentary consultation, to finance the war.

- Charles succeeded in collecting money, announcing that Spain could invade England at any time.

- The Duke and his fleet arrived on the Isle of Ré (in front of the French town of La Rochelle, which was under the control of the Huguenots at war against Cardinal Richelieu). From this location, Buckingham hoped to attack France and Spain.

- However, the promised support troops never arrived and Buckingham was forced to withdraw. On August 23, 1628, the Duke of Buckingham, who at this point was surrounded by enemies, was assassinated.

Charles’ Financial Hardship

- Having secured peace with France and Spain and having dissolved parliament, Charles devoted himself to fiscal consolidation. Since the increase of taxes had to be approved by parliament, the monarch had to find new ways to achieve his objective. He decided to support Richard Weston, 1st Earl of Portland, who was appointed Lord Treasurer.

- In 1634, the king imposed the collection of ship-money, a cash tax in favour of the navy for the defence of the coasts and merchant ships.

- Despite the fact that England was not at war, the establishment of an impressive and effective fleet was of primary importance: in those years, naval clashes between Holland and Spain were very frequent, as were pirate raids on the English coasts.

- As a result, the king ordered all port cities to provide a warship or to pay the corresponding amount in money. Although the king’s new law provoked much controversy, a large sum of money was collected and used for the expansion of the military fleet. Many complained that under the reigns of Edward I and Edward III, the tax had been applied only in cases of war.

Religious Policy

- Charles tried to bring the Church of England, predominantly Calvinist, towards a more traditional and sacramental version. This operation was joined by William Laud, who was appointed Archbishop of Canterbury in 1633.

- With the intention of bringing order, authority and prestige back to the Church, Laud promoted a series of reforms, which were largely unpopular.

- To achieve greater unity, Laud removed all non-conformist ecclesiastics and the last puritanical organisations.

- Furthermore, the archbishop was against the reformist spirit of the English and Scottish priests and believed that Calvinism should be completely abolished

in favour of Anglican liturgy. - Laud was also an active follower of the Armenian doctrine promoted by Jacobus Arminius.

- To punish those who opposed his decisions, Laud used two of the largest and most feared ecclesiastical bodies of the time: the Court of High Commission and the Court of Star Chamber, which had the task of gathering testimonies and punishing the guilty through torture. Sometimes, the Star Chamber was also given the opportunity to sentence and execute people.

- Many times, admissions of guilt had been extracted through torture. It was during Laud’s religious reorganisation that the first massive groups of settlers left for New England. The first years of Charles’ personal government were characterised by peace and an effective budget balance. However, there were numerous cases of people who rejected the laws imposed by the sovereign and Laud’s religious restrictions.

- In 1634, a ship named Griffin set off with religious dissidents, including the famous Puritan theologian Anne Hutchinson.

Policy in Scotland

- Charles and Laud encountered the most serious problems with religion in Scotland.

- When Charles left in 1633 for a trip to Scotland, where he was to be

crowned, Laud accompanied him. - The priests were culturally poor and the lands were often controlled by laypeople. Moreover, churches did not follow the same ceremonies during mass.

- Although James I had already intervened in numerous Scottish religious questions, he had not come to any resolutions. Thus, Charles and Laud tried to impose the episcopal structure of the Anglican Church. The opposition and discontent were considerable: all of Laud’s decisions were rejected.

- In 1637, a Presbyterian government was imposed: the king saw this decision as an affront to his authority. In Edinburgh, in fact, a group of aristocrats, traders, ecclesiastics, and members of the people formed a committee opposing the policy promoted by the king and Laud, which took

- the name of Covenant, stating that no change in the religious field could be accepted without the authorisation of parliament and the Presbyterian Kirks.

- The War of the Bishops was the first of the conflicts known collectively as the 1638 to 1651 Wars of the Three Kingdoms.

- When the War of the Bishops broke out in 1639, Charles tried to collect taxes and set up an army but did not obtain anything he had hoped for. The war ended with a humiliating signing of the Berwick agreement, whereby Scotland obtained civil and religious liberties.

Problems with Parliament

- Charles’ defeat in the military management of Scottish affairs led to a financial crisis, and the king could no longer impose his absolute rule. In 1640, Charles was forced to convene Parliament to try to get money.

- In November 1641, when the king returned to London from his trip to Scotland, the Chambers drew up the Grand Remonstrance.

- The Grand Remonstrance is a list of the unforgivable errors committed by Charles and his ministers and collaborators since the beginning of his reign.

- Parliament then split into two different factions... one in support of the king, one against the king.

- Soon after, the king hastily secured the royal family and left London. Meanwhile, the military situation on the Irish borders had become unbearable; it was necessary to quickly set up an army to silence the Irish revolt. However, it was decided not to entrust the command of the army to the king, who could have used it against parliament.

- When letters of Henrietta Maria, which suggested a possible alliance with the continent’s Catholic countries, were discovered, the Catholic queen was accused and arrested. Charles therefore entered parliament with a group of soldiers in order to arrest five involved members on January 4. The sovereign was forced to leave the capital and to go to the northern regions in order to gather an army, however. At the same time, the queen left for Paris.

Civil War and Charles’ Death

- Such happenings led to a division within the population: some supported parliament, while others supported the king. As a consequence, on June 14, 1645, the battle of Naseby took place, where the king’s troops were annihilated, and Charles was forced to flee to Oxford – which was subsequently besieged and conquered, forcing the king to flee again.

- Defeated, Charles decided to ask for the help of his old allies, the Scots. However, after some negotiations with parliament, the Scots stopped supporting the king. Charles was then escorted to the village of Oatlands and transferred to Hampton Court Palace in London.

- Due to his corruption and government, Charles was executed on January 30, 1649. It is said that on the day of his death, the king was wearing two cotton shirts in order to prevent people from seeing him trembling.

Image sources: