German Reformation Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the German Reformation to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Background of the Reformation

- Martin Luther and Indulgences

- Course of the German Reformation

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about the German Reformation!

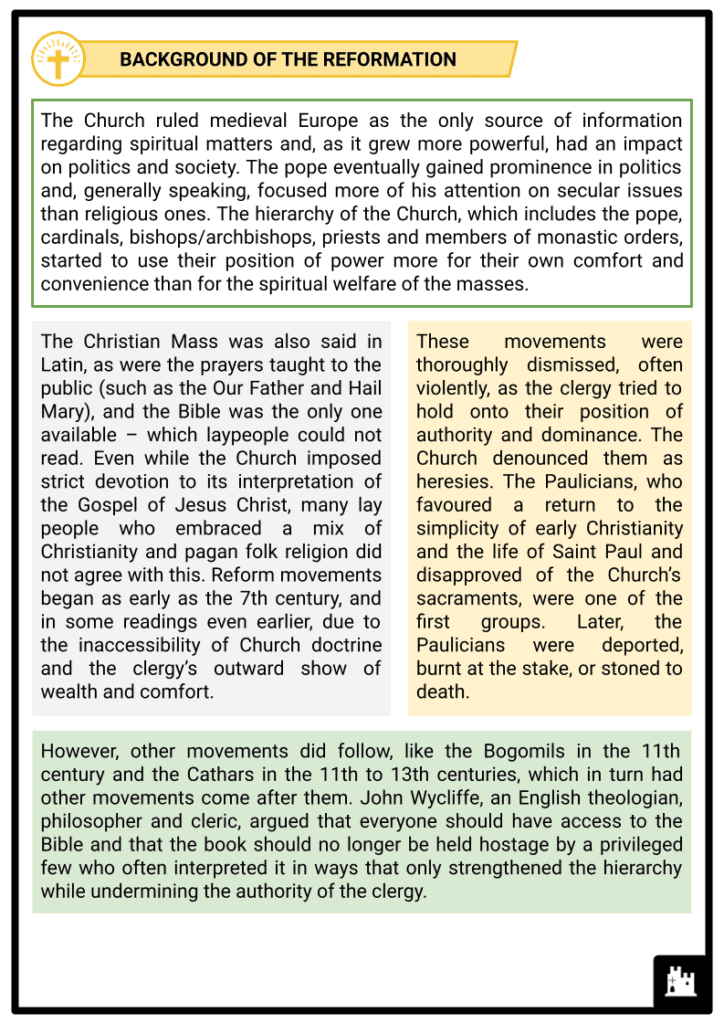

The 16th-century religious, cultural and social upheaval known as the Protestant Reformation saw the fall of the medieval Church, the emergence of unique interpretations of the Christian message, and the birth of contemporary nation-states. It is regarded as one of the important events in Western history. The Reformation was officially started in Germany on 31 October 1517, when Luther posted his famous theses to the church doors in Wittenberg.

BACKGROUND OF THE REFORMATION

- The Church ruled medieval Europe as the only source of information regarding spiritual matters and, as it grew more powerful, had an impact on politics and society. The pope eventually gained prominence in politics and, generally speaking, focused more of his attention on secular issues than religious ones. The hierarchy of the Church, which includes the pope, cardinals, bishops/archbishops, priests and members of monastic orders, started to use their position of power more for their own comfort and convenience than for the spiritual welfare of the masses.

- The Christian Mass was also said in Latin, as were the prayers taught to the public (such as the Our Father and Hail Mary), and the Bible was the only one available – which laypeople could not read. Even while the Church imposed strict devotion to its interpretation of the Gospel of Jesus Christ, many lay people who embraced a mix of Christianity and pagan folk religion did not agree with this. Reform movements began as early as the 7th century, and in some readings even earlier, due to the inaccessibility of Church doctrine and the clergy’s outward show of wealth and comfort.

- These movements were thoroughly dismissed, often violently, as the clergy tried to hold onto their position of authority and dominance. The Church denounced them as heresies. The Paulicians, who favoured a return to the simplicity of early Christianity and the life of Saint Paul and disapproved of the Church’s sacraments, were one of the first groups. Later, the Paulicians were deported, burnt at the stake, or stoned to death.

- However, other movements did follow, like the Bogomils in the 11th century and the Cathars in the 11th to 13th centuries, which in turn had other movements come after them. John Wycliffe, an English theologian, philosopher and cleric, argued that everyone should have access to the Bible and that the book should no longer be held hostage by a privileged few who often interpreted it in ways that only strengthened the hierarchy while undermining the authority of the clergy.

John Wycliffe - The Wycliffe Bible is a translation of the Bible from Latin to Middle English. More likely, Wycliffe guided his friends and companions in the translation. Wycliffe argued that the Church hierarchy, including the pope, was unbiblical and that the Bible alone was the only source of authority. He spread his ideas through lay preachers and xylography (woodblock printing) pamphlets, and by opposing the status quo, unintentionally contributing to the violent Peasants’ Revolt of 1381.

- Jan Hus, a philosopher, theologian and rector of the Charles University in Prague, was inspired by Wycliffe and worked for change while preserving Wycliffe’s writings.

- Just as Wycliffe had been, he was particularly critical of the Church’s practice of selling indulgences, which are writs that purportedly shortened ones stay in purgatory.

- His previous views were tolerated, but in 1415 he was imprisoned and beheaded for questioning the legitimacy of indulgences and the authority of the pope.

- His supporters persisted in their campaign for change before severing ties with the Church.

- Their activities helped to advance the Bohemian Reformation and ultimately resulted in the Hussite Wars, which were eventually won by Church loyalists.

MARTIN LUTHER AND INDULGENCES

- Although these reformers are seen as the forerunners of the Reformation today, there is little proof that they initially had any influence on Martin Luther, the main reformer and a German monk who also opposed the sale of indulgences. Regardless of when the Protestant Reformation began, Martin Luther is at its centre. His writings, charisma and intellect inspired a movement that he neither intended nor, doubtless, could have envisioned.

- The inability of the Church to address the suffering and causes of the Black Death pandemic of 1347–1352 dealt the Church’s power in the Middle Ages its biggest blow, not from any man or movement.

- Europe was destroyed by the plague, and the Church’s efforts to stop the spread and lessen suffering were ineffective.

- At the same time that they prayed to the Virgin Mary or the saints, people started to rely on traditional medicines and make supplications to spirits and ancestors.

- At the same time, the Holy Roman Catholic Church was the only source of spiritual authority.

- To escape hell and spend less time in purgatory, one had to put aside whatever doubts they might have had and follow the Church’s teachings.

Martin Luther - Heaven, purgatory and hell were all thought to be unquestionable realities.

- One of these teachings was the effectiveness of indulgences, which were bought to hasten one’s journey from purgatory to heaven. In 1516, when Dominican friar Johann Tetzel came to the region to provide indulgences in order to raise money for the restoration of St Peter’s Basilica in Rome, Martin Luther was already an ordained Augustinian monk, doctor of theology, and professor at the University of Wittenberg.

- Tetzel was a successful salesman who gained fame for his saying, “When the gold in the coffer rings, the rescued soul toward heaven springs,” which meant that as soon as one purchased a luxury, their loved one was delivered from purgatory fires. In general, Luther was against this practice, but Tetzel’s indulgence sales in his area were intolerable.

- Luther published his Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences, often known as his Ninety-Five Theses, on 31 October 1517.

- Tradition has it that Luther fastened these to the Wittenberg church door, but contemporary study has refuted this assertion.

- They were reproduced by Luther’s friends and allies, and thanks to the development of the printing press, whether he posted them at the church, mailed them to his bishop, or both.

- After going to other nations, such as England and France, in 1519, they rapidly expanded throughout Germany, where they had first appeared in 1440.

COURSE OF THE REFORMATION

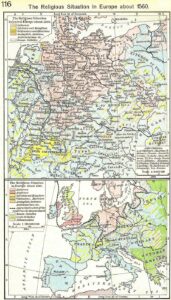

- The reform movement was started by Lutherans in a number of German imperial cities, including Ulm, Augsburg, Nuremberg, Nördlingen, Strasburg, Constance, Mainz, Erfurt, Zwickau, Magdeburg, Frankfort-on-the-Main and Bremen. On 4 May 1526, the Lutheran princes established the League of Torgau for their shared defence. By attending the Diet of Speyer in 1526, they were able to achieve the approval of the resolution stating that each person might take an attitude towards the Edict of Worms against Luther and his incorrect theology that would allow him to answer for it before God and the emperor.

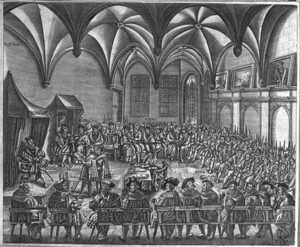

Diet of Augsburg - The territorial rulers were therefore given the freedom to spread the Reformation across their domains.

- While the Lutheran princes increased their demands, the Catholic estates grew dismayed.

- The Lutheran and Reformed estates objected to even the Diet of Speyer’s entirely moderate conclusions in 1529.

- Restoring religious unity was not going to happen, as evidenced by the talks at the Diet of Augsburg in 1530, where the estates rejecting the Catholic religion produced their confession (Augsburg Confession).

- Lutheranism and Zwinglianism were imported into various German regions as the Reformation spread ever-further.

- In addition to the aforementioned cities and principalities, by 1530 it had spread to Bayreuth, Ansbach, Anhalt and Brunswick-Lunenburg, and in the following years it reached Pomerania, Jülich-Cleve and Wurttemberg. Moreover, the Reformation made significant progress in Silesia and the duchy of Liegnitz. The Schmalkaldic League, an offensive and defensive coalition of the Protestant princes and cities, was established in 1531. Other cities and princes who had supported the Reformation joined this union, particularly following its revival in 1535.

- Count William of Nassau, Augsburg, Kempten, Hamburg, and the Count Palatine Rupert of Zweibrücken were the cities that joined the Schmalkaldic League. In an effort to end the schism, more conversations and negotiations between the religious parties were started, but they were unsuccessful. Ever more liberal use was one of the strategies the Protestants used to expand the Reformation force.

- As soon as the Diocese of Naumburg-Zeitz became vacant, Elector John Frederick of Saxony forcibly put Lutheran preacher Nicholas Amsdorf in the position and seized the secular administration. In 1542, the Reformation was forcibly imposed on Duke Henry of Brunswick Wolfenbuttel’s realms before he was exiled.

- The Reformation was almost imposed by force in Cologne itself. Some religious leaders showed delinquency by doing little to stop the innovations that were being propagated every day in larger circles.

- The Reformation gained entry into Pfalz-Neuburg and the cities of Halberstadt, Halle, etc.

- The Schmalkaldic League’s dissolution in 1547 somewhat slowed the progress of the Reformation: Hermann von Wied had to resign the Diocese of Cologne, where the Catholic Faith was thus preserved, Julius von Pflug was installed in his diocese of Naumburg, Duke Henry of Brunswick-Wolfenbuttel recovered his lands, and Hermann von Wied was forced to take up residence in the diocese of Wolfenbuttel.

- Although it was adopted in many Protestant regions, the unity formula proposed by the Diet of Augsburg in 1547–1548 (Augsburg Interim) failed to achieve its goal. The power of the emperor was shattered in the meantime by the treachery of Prince Moritz of Saxony, who made a covert agreement with Germany’s foe Henry II of France and joined forces with the Protestant princes William of Hesse, John Albert of Mecklenburg, and Albert of Brandenburg to wage war against the emperor and the empire.

- King Ferdinand called the Diet of Augsburg in 1555 at Charles’ recommendation, and it was there that the agreement known as the Religious Peace of Augsburg was reached after protracted talks. The 22 paragraphs of this accord comprised the following clauses:

- Peace and harmony were to be maintained between the Augsburg Confession and Catholic imperial estates;

- No estate of the empire was permitted to compel another estate or its citizens to alter their faith, and no estate was permitted to wage war on another estate because of religion;

- If an ecclesiastical dignitary agreed to the Augsburg Confession, he would lose his ecclesiastical rank and all associated positions and compensation; his honour and his property would be unaffected. The Lutheran estates objected to this ecclesiastical restriction:

- After 1555, neither party could seize anything from the other; the holders of the Augsburg Confession were to be allowed to retain ownership of any church property they had owned since the Reformation’s inception.

- If there is ever a dispute between the parties over land or rights, such a matter should first be adjudicated;

- No imperial estate was permitted to shield the citizens of another estate from the law;

- Without compromising the rights of the territorial lord over his peasantry, however, every citizen of the Empire had the freedom to choose one of the two authorised faiths and to practise it in another area without suffering loss of rights, honour or property;

- The free cities and knights of the empire were to be a part of this peace, and its terms were to be strictly followed by the imperial courts;

- Oaths may be given in the name of either God or His Holy Gospel.

- The religious division in the German Empire was finally cemented by this treaty; Catholic and Protestant estates are now at odds with one another. With the exception of the majority of the western portion, nearly all of Germany, from the Dutch border in the west to the Polish border in the east, the Teutonic Order’s domain in Prussia, Central Germany, Wurtemburg, Ansbach, Pfalz-Zweibrucken and other small domains with numerous free cities, had espoused the Lutheran faith. It also found more or less widespread support in the south and southeast, which remained predominantly Catholic. Calvinism also gained considerable ground.

- But the desired harmony was not established by the Peace of Augsburg. Before the start of the 17th century, a number of ecclesiastical principalities – including two archbishoprics, twelve bishoprics and countless abbeys – were reformed and secularised in violation of its explicit restrictions. To counter the Protestant Union and safeguard Catholic interests, the Catholic League was established. It was quickly followed by the Thirty Years’ War, which was extremely dangerous for Germany since it resulted in the country’s capitulation to its foes in the west and north as well as the destruction of the German Empire’s strength, riches and influence.

- The Peace of Westphalia, signed in 1648 at Munster and Osnabrück with France and Sweden respectively, established the status of the religious schism in Germany, put Calvinists and Reformed on an equal footing with the Lutherans, and granted the estates directly under the emperor the right to bring about the Reformation. Subject to the recognition of the independence of people who in 1624 possessed the ability to perform their own religious ceremonies, territorial sovereigns were afterwards permitted to compel their subjects to follow a particular religion. In Germany, state absolutism in religious subjects had now reached its peak.