Download William Harvey Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach William Harvey to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Table of Contents

Add a header to begin generating the table of contents

Summary

- William Harvey’s early life and family

- Harvey’s education

- Harvey’s association with Hieronymus Fabricius

- Harvey’s medical practice

- Harvey’s works, specifically on blood circulation

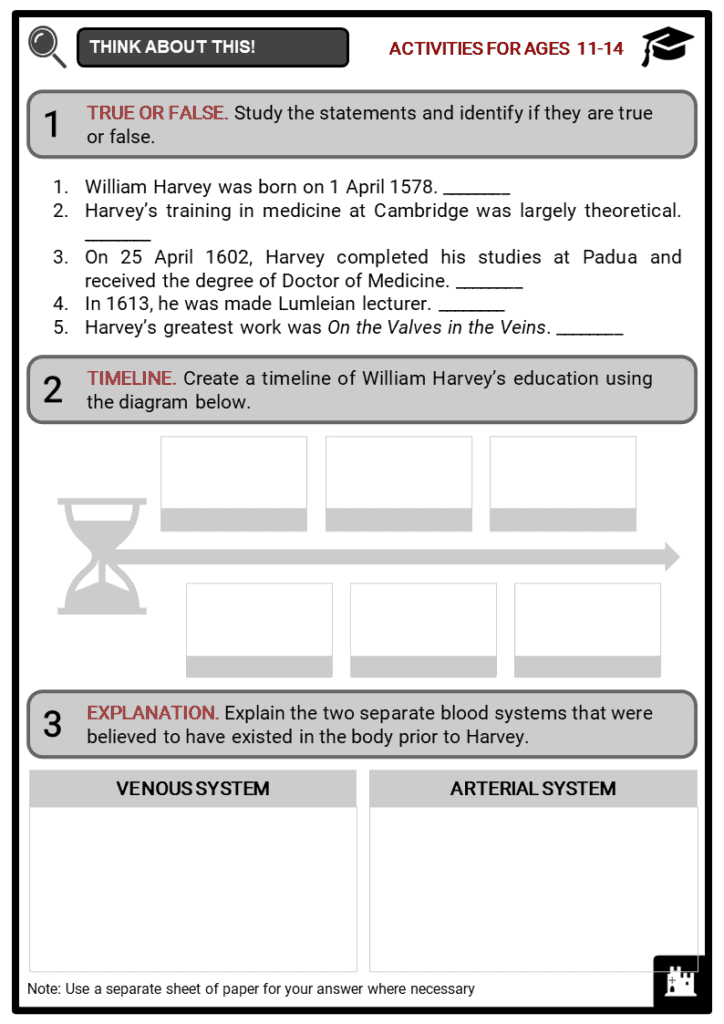

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about William Harvey!

- William Harvey was an English physician who was the first to accurately describe the human circulatory system and the manner in which the heart pumps blood throughout the body. Influenced by Italian anatomist and surgeon Hieronymus Fabricius of Aquapendente, Harvey’s greatest work was De Motu Cordis (Anatomical Account of the Motion of the Heart and Blood) in 1628.

Family

- William Harvey was born in Folkestone, Kent, on 1 April 1578. He was the eldest son of Joan and Thomas Harvey, later mayor of Folkestone.

- William had six brothers and two sisters. Of his brothers, five became successful London merchants who traded with Turkey and the Levant. One of them, Eliah, looked after William’s interests in later life and it was in his house that William died.

Education

- It seems probable that William was first sent to the local school in Folkestone, where he learnt to read and write.

- In 1588, he went to King’s School in Canterbury where he was taught Latin grammar.

- He was admitted to Caius College, University of Cambridge in May 1593, and a little later that same year he was awarded the special scholarship in medicine which had been founded in 1572 at the college by Matthew Parker, archbishop of Canterbury.

- Although Sir Charles Scarburgh, Harvey’s great friend at the end of his life, said that it was in Padua that Harvey first decided to make medicine his career, it would seem that his interest in that subject started at a much earlier age.

- From the details of the scholarship which he held for a period of six years, it is known that Harvey spent the first three years studying subjects useful to medicine: the classics, rhetoric, philosophy, and perhaps some mathematics.

- During the next three years, Harvey studied those subjects which make up the base of medicine itself. However, at Cambridge at this time these studies were limited to readings and discussions of writings of Hippocrates and Galen, and other medical textbooks.

- From time to time, Harvey may have seen an anatomical demonstration, for the Regius Professor of Physics was supposed to dissect a body each winter, and Caius College had a special arrangement by which it was allowed each year to dissect two bodies of executed criminals. Still, Harvey’s training in medicine at Cambridge was largely theoretical.

- For the real instruction in medicine and surgery, medical students back then had to go to schools in such cities as Padua, Verona, Montpellier and Paris on the European continent. Harvey took his B.A. degree in 1597 and finally left Cambridge in October 1599.

University of Padua and Association with Fabricius

- While still a student at Cambridge, it seems likely that Harvey travelled to France, Germany and Italy and probably decided to study at the University of Padua. The exact date of when he first went there is unknown, but during the year 1600 he was elected representative of the English nation by the English students at the university.

- The medical school at Padua was then at the height of its fame. Anatomical studies were flourishing under Hieronymus Fabricius of Aquapendente, who held first the chair of surgery and later those of anatomy and embryology.

- Fabricius was the pupil and successor of Gabriel Fallopius, who had carried on the great renaissance of anatomical studies begun in Padua by Vesalius.

- Although Galileo had been appointed to the chair of mathematics at Padua in 1592 and was teaching there in Harvey’s time, there is no indication in Harvey’s works that he knew anything of Galileo or of his teaching. Harvey’s chief debt in Padua was to his master and friend Fabricius.

- When Harvey came to Padua, Fabricius was an old man, and although many of his writings had not then been published, the work for most of them had already been done.

- His most important work, On the Valves in the Veins, appeared in Harvey’s first year at Padua, but Fabricius had demonstrated the existence of valves in his class as early as 1578.

- The influence of this work on Harvey is incontestable, for Fabricius showed that the valves were always placed so that their mouths were directed towards the heart. However, Fabricius did not see their relevance to blood circulation.

- Fabricius’ work in embryology had begun at least as early as 1589, although his book The Formed Foetus was not published until 1604. The Formation of the Egg and of the Chick did not appear until 1619. Both of these books were of capital importance in Harvey’s own work On the Generation of Living Creatures (1651).

- Fabricius’ work on the structure of muscle and its method of action was not published until 1614 (he died in November 1613), but it was used by Harvey in his notes for his unpublished treatise On the Local Movement of Animals.

- While at Padua, Harvey attended lectures in the anatomical theatre built in 1594. It still stands today. It is a small room, about twenty-five by thirty feet in size, and from an oval pit in the centre six galleries rise which provide cramped accommodation for about three hundred students.

- As the representative of the English Nation, Harvey had the right to stand in the first gallery.

- The only lighting was provided by candles and lamps.

- The professor sat at the dissecting table in the centre of the floor, while the demonstrator showed the students the various parts of the body as they were discussed.

- Around the table were a number of benches for various dignitaries of the universities and cities of Padua and Venice.

Medicine Practice

- On 25 April 1602, Harvey completed his studies at Padua and received the degree of Doctor of Medicine. On his return to England in the same year, he settled in London.

- However, his degree did not give him the right to practice medicine within the City. The licence to do this had to be granted by the College of Physicians, who were particularly concerned to prevent quacks from deceiving the public.

- In 1603, Harvey applied to the college as a candidate for admission.

- He was examined in the spring of that year and was given leave to practise until his next examination which was fixed for April of the following year. Harvey was finally admitted as a member of the college.

- In November, he married Elizabeth Browne who was the daughter of Dr Lancelot Browne, the physician to Queen Elizabeth I and to King James I. His wife died in 1645 and they had no children.

- In 1607, Harvey was admitted as a Fellow of the College of Physicians, and two years later asked to be appointed as a physician to the Hospital of St. Bartholomew. The governors of the hospital agreed to appoint him as soon as the existing physician died or retired.

- As this happened in August 1609, Harvey was called upon immediately to fill his place. His duties as a physician were to attend the hospital at least twice a week throughout the year and more often if necessary to examine the sick brought before him in the hall of the hospital, and to prescribe medicines for them.

- For twenty years after his appointment, Harvey regularly performed his duties as the hospital’s physician in spite of his increasing practice as a doctor in London, his work for the College of Physicians, and his own experimental observations.

- In 1613, Harvey was elected a censor of the College of Physicians. Two years later, he was made Lumleian lecturer.

Blood Circulation

- In 1628, Harvey’s greatest work, Anatomical Account of the Motion of the Heart and Blood (De Motu Cordis) was published in Frankfurt. In this work, he explained with exemplary clarity his observations of the movement of the heart and blood, his theory of blood circulation, and his experimental proofs of the validity of his theory.

- Through his work, Harvey was able to refute many of the standard beliefs of blood circulation. He established that:

- Blood in the arteries and the veins is all of the same origin, not manufactured in different parts of the body.

- The blood sent through the arteries to the tissues is not consumed there.

- The circulation mechanism is designed for movement of liquid, not air. The blood on the right side, although carrying air, is still blood.

- The heart, not the liver, is the source of blood movement.

- The heart contracts at the same time as a pulse is felt.

- The ventricles squeeze blood into the aorta and pulmonary artery.

- The pulse is not produced by the arteries pulling blood in, but by blood being pushed by the heart into the arteries, enlarging them.

- There are no vessels in the heart’s septum: all of the blood in the right ventricle goes to the lungs and then through the pulmonary veins to the left ventricle.

- Similarly, all of the blood in the left ventricle is sent into the arteries, round by the smaller veins into the venae cavae, and then to the right ventricle again. In this way, the circulation is complete. The blood has come back to where it began its circuit of the body.

- There is no to-and-fro movement of blood in the veins, but a constant flow of blood to the heart. (Famous Scientists 2015).

- He wrote that for nine years he had been working on this subject, slowly drawing the inevitable conclusions from his observations and experiments. By determining the correct path the blood took through the body, he concluded that the amount and rate of passage of blood from the heart necessitated that the blood return to the heart.

- Prior to Harvey, Galen had been an influential medical authority for many centuries. His studies say there were two separate blood systems in the body.

- One carried the venous blood that uses the veins to distribute nutrition from the liver to the rest of the body.

- The other carried the arterial blood that uses the arteries to distribute heat and life from the heart to all parts of the body.

- In present times, these two systems are now understood as oxygenated and deoxygenated blood.

- These existing beliefs made Harvey’s theory so revolutionary that there was little wonder that he met with some bitter opposition, especially since his claims were opposed to that of the great Galen’s.

- Some time at the beginning of 1631, Harvey became physician-in-ordinary to King Charles I.

- From then on, his fortunes were linked with those of the king and they became close personal friends. Charles was genuinely interested in Harvey’s work.

Image sources:

- https://todayinsci.com/H/Harvey_William/HarveyWilliam-Quotations.htm

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:The_Kings_School_Canterbury.jpg

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hieronymus_Fabricius