Battle of Trafalgar Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the Battle of Trafalgar to your students?

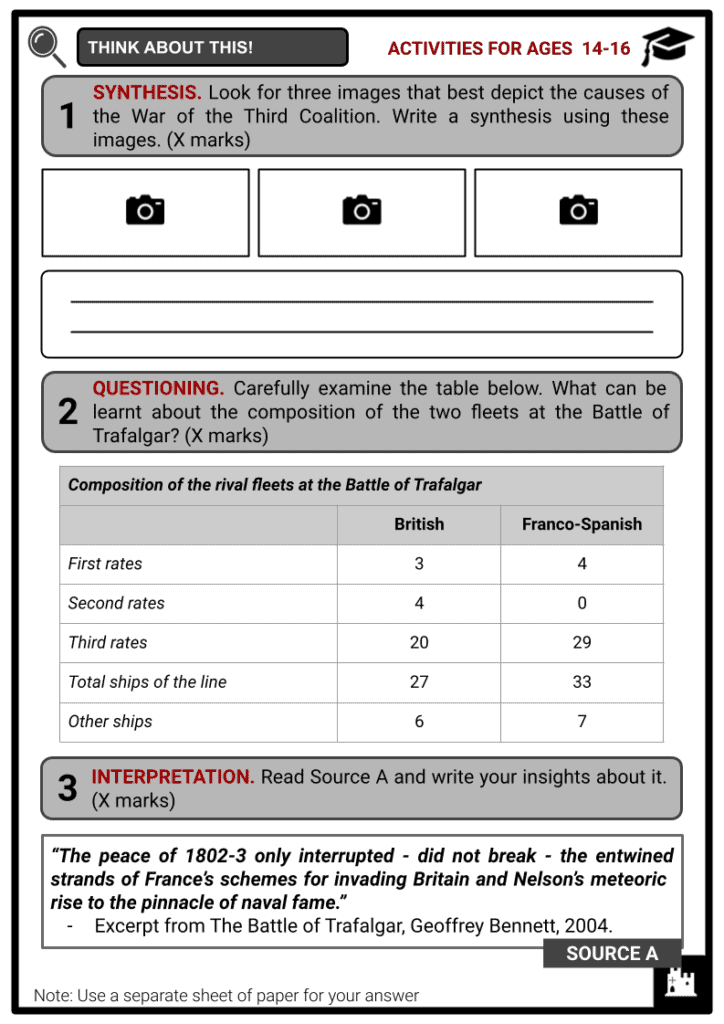

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Outbreak of the War of the Third Coalition

- Prelude to the battle

- Account of the battle

- Aftermath of the battle

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about the Battle of Trafalgar!

Fought on 21 October 1805 on the Spanish coast, the Battle of Trafalgar was a naval engagement between the British Royal Navy and the combined Franco-Spanish fleet during the War of the Third Coalition of the Napoleonic Wars. Despite the numerical advantage of the allied navies, Britain successfully overpowered its opponent, thereby reinforcing its naval supremacy. This British victory, however, failed to significantly impact the War of the Third Coalition.

Outbreak of the War of the Third Coalition

- Europe had been caught up in the French Revolutionary Wars since 1792. By 1797, the French Republic defeated the armies of the First Coalition that consisted of Britain, Russia, Prussia, Spain, Holland, and Austria. A Second Coalition, this time led by Britain, Austria and Russia, was formed in 1798. By 1801, this too was defeated leaving Britain the only opponent of the new French Consulate under the leadership of Napoleon Bonaparte.

- In March 1802, the Peace of Amiens was agreed to by France and Britain ending the hostilities between the two, albeit, temporarily.

- It was the first time in ten years that Europe was at peace. The terms of the peace agreement included Britain returning most of its recent conquests and the French withdrawal from Naples and Egypt,

- The implementation of the terms grew increasingly difficult as many issues arose between the two sides.

- Napoleon was angered by the failure of the British troops to evacuate the island of Malta.

- When he sent an expeditionary force to re-establish control over Haiti, tension further increased, setting the stage for the Napoleonic Wars.

A portrait of Napoleon in his coronation robes - This caused Britain to declare war on France in May 1803, which in turn stimulated Napoleon’s ambition of restoring the French Empire.

- In 1804, the British government attempted to remove Napoleon from power but this assassination plot was foiled.

- That same year, Napoleon was declared the Emperor of France, with the intention to discourage conspiracy against his life and to secure the Bonaparte dynasty after his death.

- From 1804 to 1805, Napoleon’s actions in Italy and Germany acted as a catalyst for the renewal of a coalition against the French Empire, known as the Third Coalition.

- Russia, Sweden and Austria joined Britain against France.

- The War of the Third Coalition had begun. It was the first of the Napoleonic Wars, and one of the most famous.

- Napoleon was keen to defeat the coalition and invade Britain. In fact, he had already assembled an invasion force meant to strike at England at Boulogne in northern France.

- This formed the core of La Grande Armée. By 1805, it had grown to a force of 350,000, was well-equipped and sufficiently trained.

- Furthermore, he organised a cavalry reserve to support the French army.

- For an invasion to happen, Napoleon had to neutralise Britain’s greatest strength, the Royal Navy.

- In contrast to Britain’s experienced and well-trained corps of naval officers, the French navy had lost some of the best officers during the early part of the French Revolution.

- The main French fleets were at Brest in Brittany and at Toulon on the Mediterranean coast whilst smaller squadrons were harboured at the ports on the French Atlantic coast. The French fleet was joined by the Spanish, so a fleet based in Cádiz and Ferrol was also available.

Prelude to the battle

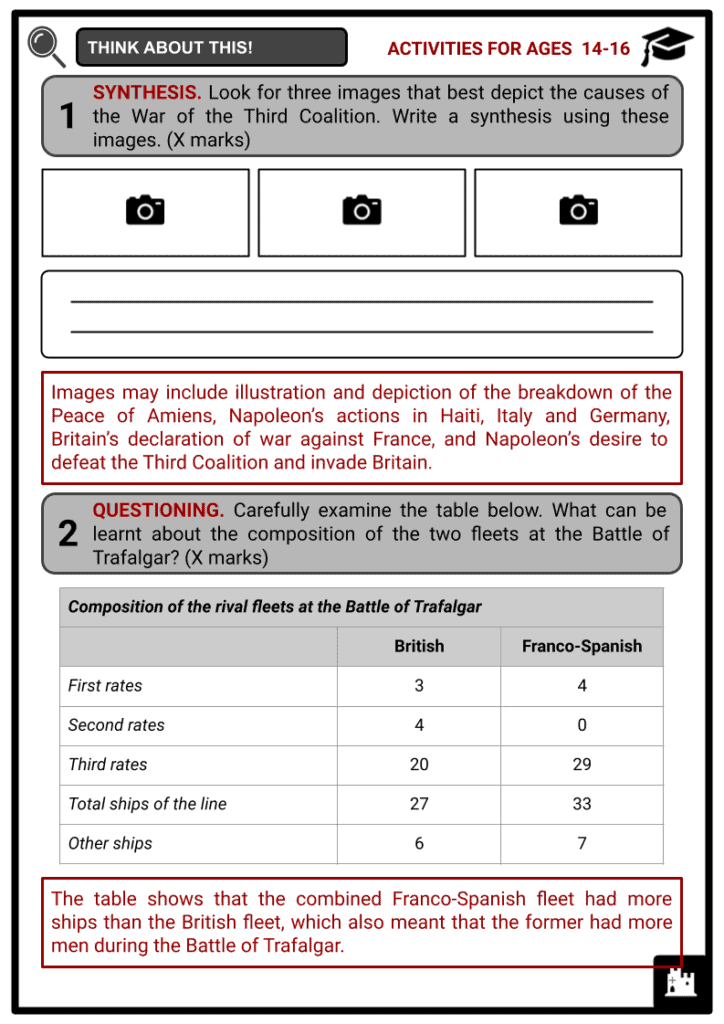

- The French Mediterranean fleet was under the command of Vice Admiral Pierre-Charles Villeneuve whilst the British fleet was headed by Vice Admiral Horatio Lord Nelson. Villeneuve’s fleet successfully evaded Nelson’s when the British were blown off station by storms. Thinking that the French intended to make for Egypt, Nelson commenced a search of the Mediterranean.

- Villeneuve instead took his fleet through the Strait of Gibraltar and met with the Spanish fleet in Cádiz, sailing as planned for the Caribbean.

- Once Nelson realised the route of the French, he set off in pursuit.

Scope of Nelson’s search in the Mediterranean - However, as a result of false information, Nelson missed the French fleet by just days in the West Indies.

- Villeneuve then returned from the Caribbean to Europe, with the goal of breaking the blockade at Brest.

- When the British spotted the French heading further north, Admiral William Cornwallis was immediately ordered to merge with Vice Admiral Sir Robert Calder’s fleet to block the French from entering the Channel.

- When Calder intercepted the French, the Battle of Cape Finisterre ensued fought between the rival fleets. It ended in British victory with two of the Spanish ships captured.

- The aftermath of the battle saw Villeneuve abandoning his plan and sailing back to Ferrol in northern Spain.

- He then received orders from Napoleon to sail northward toward Brest and follow the main plan.

- His force was to join Vice Admiral Ganteaume’s force at Brest, along with a squadron under Captain Allemand. This would have given Napoleon a combined force of 59 ships of the line.

- On 11 August 1805, Villeneuve, fearing the British were observing his manoeuvres, sailed southward instead toward Cádiz.

- With no sign of Villeneuve’s fleet by 25 August, the three French army corps’ invasion force near Boulogne broke camp and marched into Germany.

A depiction of Nelson - This meant that there was now no immediate threat of invasion.

- Meanwhile, when word reached Britain on 2 September about the Franco-Spanish fleet in Cádiz harbour, Nelson, who had returned home to Britain in August, had to wait for two weeks before his ship was ready to sail.

- A detached force of 20 ships that sailed southward to engage the enemy forces in Spain back in August formed the nucleus of the British fleet at Trafalgar.

- Nelson joined on 28 September and took command of the British fleet.

- At this point, Nelson’s fleet badly needed provisioning. As British ships continued to arrive, the fleet was up to full strength by 15 October.

- Villeneuve’s fleet at Cádiz also experienced serious supply shortage and his ships were ill-equipped. Additionally, most of the French crews lacked training and experience.

- The supply situation of the Franco-Spanish fleet began to improve in October.

- When Villeneuve heard the news of Nelson’s arrival, he was reluctant to leave port. After his captains held a vote on the matter, the Franco-Spanish fleet decided to stay in harbour, despite Napoleon’s earlier orders to put to sea at the first favourable opportunity in order to join with Spanish ships of the line at Cartagena and go to Naples.

Account of the battle

- The Franco-Spanish fleet under Villeneuve at Cádiz was in disarray as some French captains wanted to follow Napoleon’s orders. On 18 October, Villeneuve changed his mind and commanded his fleet to sail at once despite the light winds. This sudden decision was due to the news that he was to be replaced by Francois Rosily and intelligence that a detachment of a number of British ships had docked at Gibraltar. Thinking that the British fleet was now weak, Villeneuve made for the Channel.

- The calm weather slowed the progress of the Franco-Spanish fleet, which left the harbour in no particular formation. This was favourable to the British.

- In the evening of 20 October, a force of 18 British ships of the line in pursuit of Villeneuve’s fleet had been spotted, leading the latter to begin preparations for battle. The fleet then was ordered into a single line.

- On 21 October, Nelson’s fleet was once again spotted in pursuit from the northwest with the wind behind it. Villeneuve twice changed his orders regarding the formation, resulting in further disorder in his fleet.

- Villeneuve ordered his men to prepare for battle. At this point, his fleet was between the British and Cape Trafalgar. The British frigate continued to keep watch of the opponent. Meanwhile, Nelson’s fleet was still forming the lines in which it would attack.

- At 8 am, Villeneuve ordered his fleet to turn about and sail back to Cádiz. However, the very light wind made manoeuvring difficult. This again resulted in an uneven formation of the fleet.

- Nelson’s entire fleet was visible to Villeneuve by 11 am. As they drew closer, the irregular formation and the uneven space of the rival ships were revealed to them. However, it became evident that the combined fleet had more men and guns. Around noon, the Battle of Trafalgar opened.

- The British Fleet attacked in two squadrons in line ahead: one was headed by Nelson in Victory while another by Vice Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood in Royal Sovereign. Nelson intended to cut the opponent’s fleet at a point one third along the line, with Collingwood attacking the rear section. With the light wind, Villeneuve’s fleet would be unable to turn back and take part in the battle. This would leave a section of the Franco-spanish fleet heavily outnumbered.

- Collingwood sailed towards the opponent significantly ahead of Nelson. The light winds again made all the ships move extremely slowly, and the foremost British ships were heavily bombarded by the allied ships for almost an hour.

- Villeneuve then signalled to fire at Royal Sovereign as it approached the allied line. Despite being under fire, Collingwood was able to break the line just behind one of the Spanish warships. The British ships including the Victory remained to be engaged by the enemy. A number of the British crews were either killed or wounded.

- Victory cut the enemy line between Villeneuve’s flagship Bucentaure and Redoutable. It then engaged the Redoutable whilst Bucentaure was left to the next three ships of the British windward column such as Temeraire, Conqueror, and HMS Neptune.

- Skirmishes followed. The French crews gathered for an attempt to board and take Victory. Nelson was struck by a bullet in the left shoulder and was subsequently carried below decks.

- Victory’s gunners were called on deck to fight boarders but were forced back below decks by French grenades.

- Temeraire then fired on the exposed French crew aboard the Redoubtable, causing many casualties. As a result, the French captain of Redoubtable surrendered. Meanwhile, the other British ships engaged the isolated Bucentaure. Similarly, the Spanish Santísima Trinidad was isolated and overwhelmed, surrendering after three hours.

- As several British ships entered the battle, the ships of the Franco-Spanish fleet were eventually overpowered. Twenty-two vessels of the combined fleet were captured by the British. On the contrary, the British lost none. The relatively unengaged Franco-Spanish van, commanded by Rear Admiral Le Pelley, initially attempted to provide assistance but later sailed away from the fighting and returned to Cádiz.

- Nelson died three hours after being hit whilst Villeneuve was taken prisoner aboard his flagship.

Aftermath of the battle

- The French and Spanish suffered significant casualties at the Battle of Trafalgar, with more than 4,000 killed, 2,500 wounded and around 8,000 captured. British deaths amounted to 458 and 1,208 were wounded. Following the capture of a number of allied ships, a rescue mission was launched by the Franco-Spanish.

- The Franco-Spanish threat led Collingwood to summon his most battle-ready ships amidst the blowing storm.

- Due to the strong winds and heavy seas, most of the British prizes broke their tow-ropes.

- Collingwood ordered his men to cast off towing their prizes and proceeded to protect the remainder of the captured Franco-Spanish vessels.

A depiction of the gale after the Battle of Trafalgar - The numerically inferior Franco-Spanish squadron refused to approach and attack the British. Similarly, Collingwood decided against seeking action.

- The Franco-Spanish squadron managed to retake two Spanish ships of the line which had been abandoned by their British captors and took them in tow to Cádiz.

- The Battle of Trafalgar took place the day after the Battle of Ulm, in which the French were victorious against Britain’s ally, Austria. Napoleon did not learn about Trafalgar for weeks. And when he finally did, he censored the Franco-Spanish defeat for over a month. The British victory at Trafalgar ensured that Britain’s Royal Navy was never again seriously challenged by the French fleet in a large-scale engagement. Additionally, Napoleon’s plans of invading Britain were never revived. However, this battle failed to bring significant impact on the remainder of the War of the Third Coalition.

Image Sources

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/70/Battle_Of_Trafalgar_By_William_Lionel_Wyllie%2C_Juno_Tower%2C_CFB_Halifax_Nova_Scotia.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5e/Napoleon_in_Coronation_Robes_by_Fran%C3%A7ois_G%C3%A9rard.jpg/800px-Napoleon_in_Coronation_Robes_by_Fran%C3%A7ois_G%C3%A9rard.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4b/Nelson%27s_Search_in_the_Mediterranean.png/1280px-Nelson%27s_Search_in_the_Mediterranean.png

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/72/HoratioNelson1.jpg/800px-HoratioNelson1.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/thumb/e/e9/Trafalgar%2C_ships_scattered.jpg/1024px-Trafalgar%2C_ships_scattered.jpg