Download First Italian War of Independence Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach First Italian War of Independence to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Table of Contents

Add a header to begin generating the table of contents

Summary

- Italy before the revolutions

- The Revolutions of 1848

- Timeline of the First Italian War of Independence

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about The First Italian War of Independence!

- Italy was divided into several states and kingdoms under different rulers since the 6th century. The spread of revolutionary ideas in the early 19th century led to a growing movement that called for greater autonomy and power for the Italian states, which came to be known as Risorgimento.

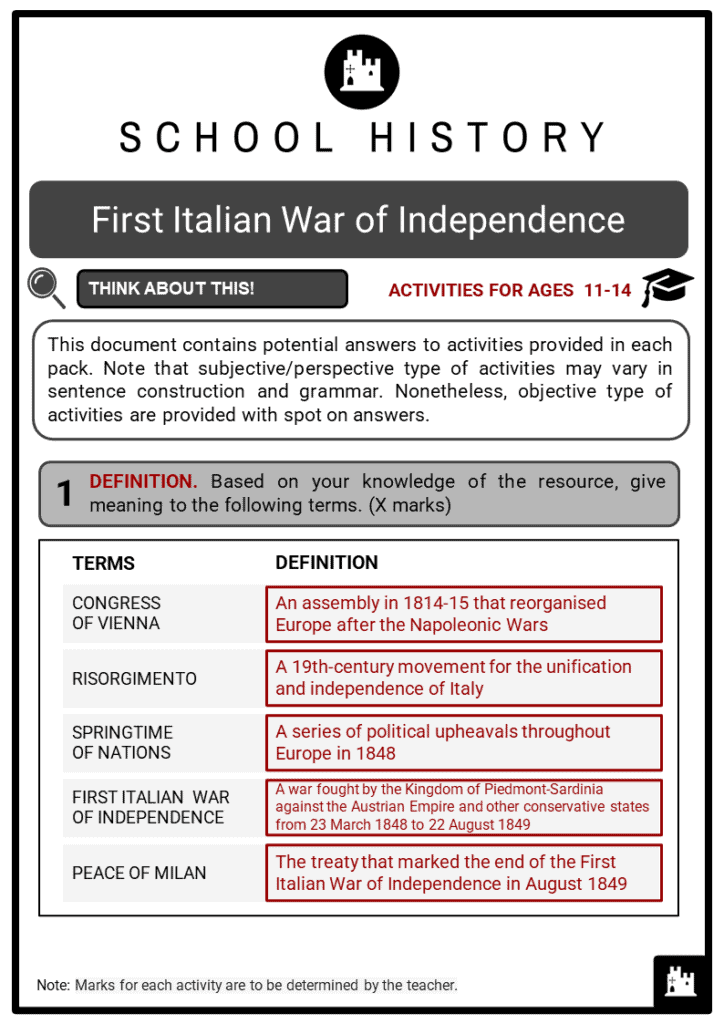

- Driven by this movement, the First Italian War of Independence began on 23 March 1848 when Charles Albert, king of Piedmont-Sardinia, declared war against the Austrian Empire. The Italians won a few victories until the tide turned in favour of the Austrians. The war officially ended with the abdication of Charles Albert in favour of his son, the signing of the Peace of Milan, and the fall of Venice in August 1849.

Italy before the revolutions

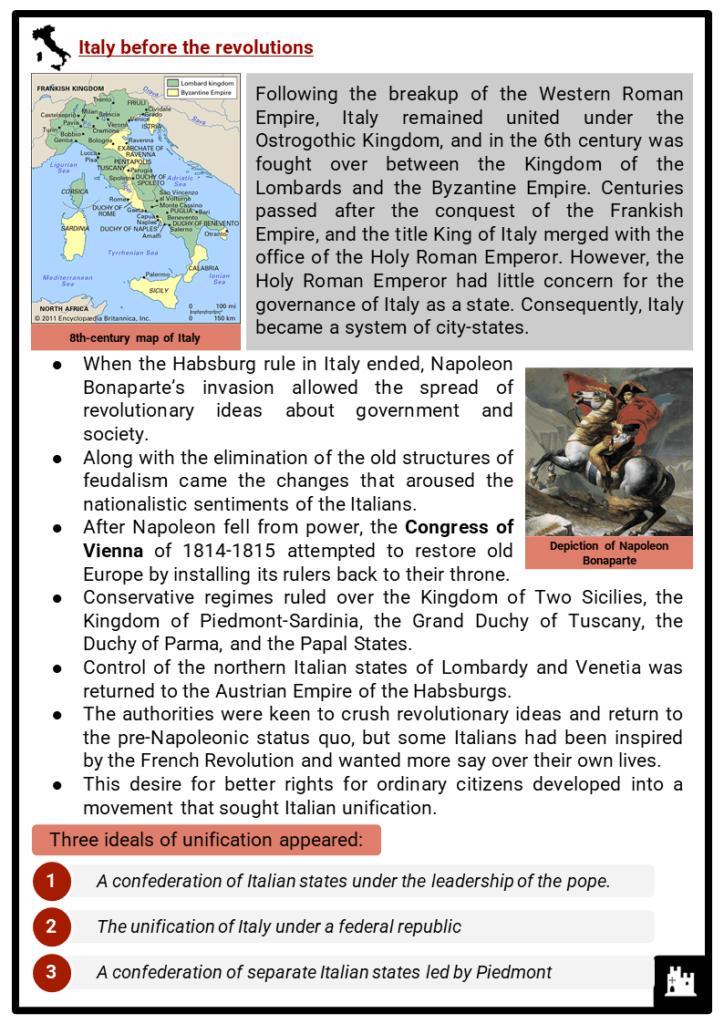

- Following the breakup of the Western Roman Empire, Italy remained united under the Ostrogothic Kingdom, and in the 6th century was fought over between the Kingdom of the Lombards and the Byzantine Empire. Centuries passed after the conquest of the Frankish Empire, and the title King of Italy merged with the office of the Holy Roman Emperor. However, the Holy Roman Emperor had little concern for the governance of Italy as a state. Consequently, Italy became a system of city-states.

- When the Habsburg rule in Italy ended, Napoleon Bonaparte’s invasion allowed the spread of revolutionary ideas about government and society.

- Along with the elimination of the old structures of feudalism came the changes that aroused the nationalistic sentiments of the Italians.

- After Napoleon fell from power, the Congress of Vienna of 1814-1815 attempted to restore old Europe by installing its rulers back to their throne.

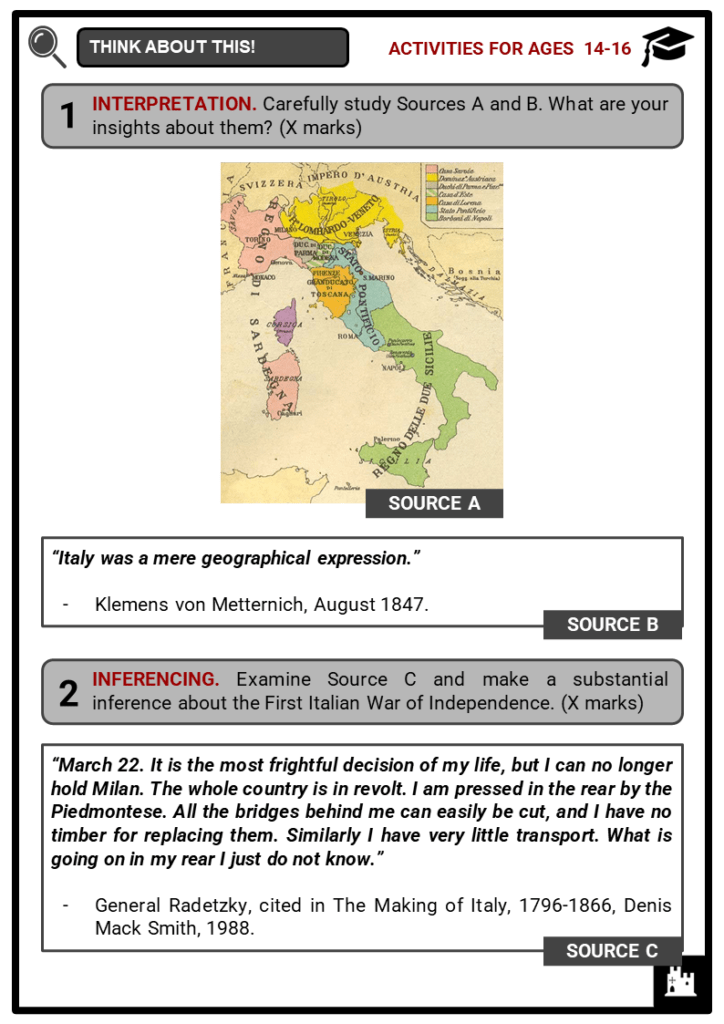

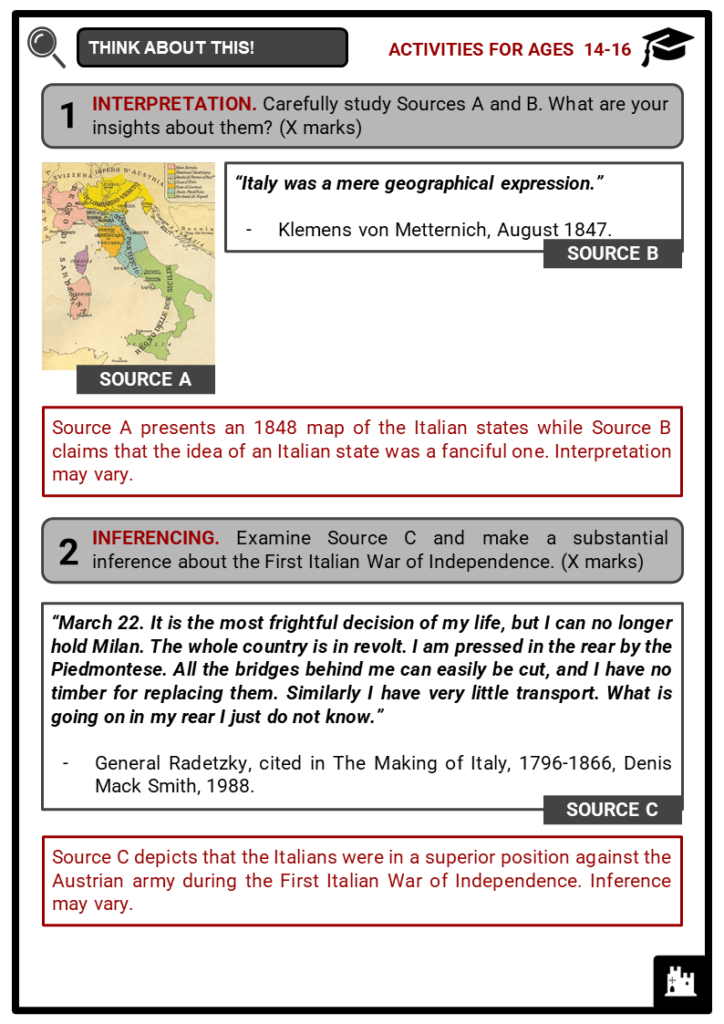

- Conservative regimes ruled over the Kingdom of Two Sicilies, the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia, the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, the Duchy of Parma, and the Papal States.

- Control of the northern Italian states of Lombardy and Venetia was returned to the Austrian Empire of the Habsburgs.

- The authorities were keen to crush revolutionary ideas and return to the pre-Napoleonic status quo, but some Italians had been inspired by the French Revolution and wanted more say over their own lives.

- This desire for better rights for ordinary citizens developed into a movement that sought Italian unification.

- Three ideals of unification appeared:

- A confederation of Italian states under the leadership of the pope.

- The unification of Italy under a federal republic

- A confederation of separate Italian states led by Piedmont

- The growing movement for greater autonomy and power for Italian states came to be known as Risorgimento. During the 1820s and 1830s, there were various attempted revolutions across Italy, but these were immediately suppressed by the authorities. As the Italian states remained fragmented, secret societies were formed to fight the old system of government. Members of these societies were given stiff penalties and some were forced into exile. Thus, many of the key intellectual and political leaders of Risorgimento operated from exile.

The Revolutions of 1848

- At the beginning of 1848, Europe witnessed its most widespread revolutionary wave, now often referred to as the Springtime of Nations or the Year of Revolution. The increasingly radical widespread protests affected more than fifty countries with France, the states of the German Confederation, the Italian states, and the Austrian Empire having the most important revolutions.

- Inspired by the liberal changes effected in Rome with the election of the new pope, the Revolutions of 1848 in Italy began in Sicily and affected other parts of Italy, particularly Lombardy-Venetia, Sardinia and the Papal States.

- On 12 January 1848, the people in Sicily demanded a provisional government that was independent of the mainland.

- The nobles called for the restoration of the constitution of 1812 including the principle of representative democracy and the centrality of parliament in the government of the state.

- These changes were initially resisted by Ferdinand II of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies but were instituted eventually when revolts erupted in Salerno and Naples.

- The king unwillingly granted a constitution that provided for an elected chamber of deputies, but placed no limits on the king’s power and authority.

- Whilst the idea of creating a confederation of all the states of Italy was put forward by the Sicilian parliament, it did not come to fruition.

- Meanwhile, in the Lombardy city of Milan, an anti-Austrian campaign was launched in early January but successfully dispersed by Austrian troops led by General Josef Radetzky.

- With harsher taxes in effect in the region, the protests resurfaced on 18 March when news of the uprising in Vienna and the fall of Klemens von Metternich reached the city. This became known as the Five Days of Milan.

- Backed by the clergymen, the people in the city took to the streets, raised barricades and urged the participation of the rural population. With the demonstration of Italian unity, a provisional government of Milan was formed.

- Prior to the revolts in Milan, rulers in other parts of Italy followed in the footsteps of Ferdinand II in granting a constitution. On the contrary, the Austrian Empire refused to give in to popular pressure and instead, suppressed the opposition in Venice and Milan, as well as the student demonstrations in the university cities of Padua and Pavia. However, the Radetzky-led Austrian army lost nearly all of Lombardy-Venetia a few days after the Five Days of Milan and retreated into the Quadrilateral fortress.

Timeline of the First Italian War of Independence

- Charles Albert grew popular as many regarded him as the liberal monarch willing to sacrifice power for the good of the people. Although it was a risky decision, he declared war on Austria on 23 March 1848. This started the First Italian War of Independence. The king saw this as an opportunity to increase his power by harnessing Risorgimento and placing himself at the head of the campaign to expand his own kingdom.

- Charles Albert gained more support from his fellow princes who pledged to send reinforcements. Leopold II, Pope Pius IX and Ferdinand II sent troops to aid the Piedmontese army. With many people on his side, Charles Albert led the attack on the Quadrilateral fortress from all sides.

- Over the next few days, the Italians reached and crossed the border into Lombardy. They then slowly advanced towards the Mincio River, which marked the border between Lombardy and Venetia, allowing the Austrians to carry out an orderly retreat to strong positions. The first military clashes of the war came at various crossings of the Mincio, where from 8 to 11 April the Austrian rearguard failed to prevent the Italians from moving into Venetia.

- Meanwhile, Austrian reinforcements were coming, marching into Venetia from the east. By 27 April, the Italians were besieging the Austrian-held fort at Peschiera, and three days later there was a clash at Pastrengo as they successfully forced the Austrians out of several strongholds in the vicinity.

- The support of the princes and the pope was instrumental in the Austrian defeat. A few victories were won by the Piedmontese until the tide turned in favour of the Austrians.

- Fearing a religious schism between Austria and Rome, the pope withdrew his troops from the war front. Tuscany and Naples followed suit. These damaged the position of the revolutionaries of Piedmont and Lombardy, as well as the popularity of the pope in the Papal States. Ignoring the wishes of the pope, the papal troops and their commander, Giovanni Durando, chose to remain and fight.

- The Battle of Santa Lucia on 6 May saw the Piedmontese army attack Austrian-held villages west of Verona. Although there was some success, the failure of attacks in other parts of the line led to the Italians abandoning the gains they had made rather than leaving their troops exposed.

- The Austrians were able to retake the villages without opposition, and the battle marked a turning point in the campaign, where the Italians lost the initiative they had held up until that point.

- Two days later, the other Austrian army, under General Laval Nugent, fought the papal troops at the Battle of Cornuda. When expected reinforcements failed to arrive, the Papal Army was forced to retreat. Ill health forced Nugent to hand command over to Georg Thurn, who marched the troops to link up with Radetzky’s Austrians at Verona.

- The aim of the Austrians was to break the siege of Peschiera, but an attempt to break through the Italian lines at Goito on 30 May failed, and on that very same day, the Austrians at Peschiera surrendered. Charles Albert was hailed by his victorious troops as the ‘King of Italy’. However, this would prove to be the high-water mark of Italian success. On 11 June, the papal troops in the east were forced to withdraw from the war after losing the battle for the city of Vicenza. Their departure weakened the Italian position in Venetia and allowed the Austrians to regain control of Padua, Trento and Palmanova.

- After several weeks of inactivity, troops from the Savoy region retook the town of Governolo from the Austrians. Although it was an impressive victory, the Italians were now overextended.

- The Battle of Custoza, playing out from 22-27 July, saw the two armies confront each other in almost equal numbers. At first, the Italians were able to repel Austrian attacks around Rivoli, but over the next few days the Austrians gained several crossings over the Mincio River.

- By 27 July, the Italians were falling back. Charles Albert wanted to negotiate a truce but, finding the Austrian demands excessive, decided instead to retreat to Milan. The city was still in the hands of a provisional government after ejecting the Austrian garrison earlier in the year, and Charles Albert hoped to gain control of it for Piedmont and the Sardinian crown.

- In Milan, the Italian soldiers found the citizens ready to resist the Austrian army to the death. However, Charles Albert was concerned at the lack of supplies and decided to abandon the city. He left under cover of darkness, protected by armed guards against any Milanese citizens who might take violent objection to his decision.

- On 6 August, Charles Albert’s armies had withdrawn into Piedmont, back inside the Sardinian territory. On 9 August, the Salasco armistice was signed with the Austrians. Although the fighting had officially stopped, Italy had not returned to the pre-1848 status quo. Venice was still in rebel hands and had agreed to be annexed by Sardinia.

- In the Papal States, Count Pellegrino Rossi was appointed by the pope in September to oversee the government. His biased reforms cost him his life in November. His death was celebrated by the people in Rome. The pope managed to flee to Gaeta in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. Without a local government in Rome, the leaders called for an assembly to be elected on universal manhood suffrage. One of the elected people, Giuseppe Mazzini seized upon the opportunity to help create a new Roman Republic and took the office that was offered him in February 1849.

- Under Mazzini’s influence, taxes were abolished throughout the Papal States, freedom of religion was established and a large contingent of troops were sent to aid Albert in his fight against the Austrian Empire. However, these actions turned out to be counterintuitive for the state: the major source of income was eliminated and Rome was left extremely vulnerable to attack with the lack of sufficient troops at home.

- In early March 1849, the Chamber of Deputies in the Kingdom of Sardinia voted to break the terms of the armistice and resume hostilities against Austria.

- Charles Albert officially declared war on 20 March, but the Austrians had not wasted those few weeks and were ready with a surprise invasion of Piedmont. On 23 March, the two armies met at the Battle of Novara.

- Although the attacking initiative changed hands several times over the course of the day, the end result was a heavy defeat for Piedmont. That night, Charles Albert announced that he would be abdicating as king of Sardinia in favour of his son and heir, Victor Emmanuel II. The new king’s first duty was to meet Radetzky to negotiate the terms of the armistice. The Italians were forced to allow the Austrians to keep garrisons in their territory, and to pay reparations. The armistice of Vignale was followed by the Peace of Milan, which officially came into force on 6 August.

- In the months following the Battle of Novara, other Italian states were gradually returned to their former rulers. The Papal States fell under the power of the French who aimed to restore the pope, effectively ending the Roman Republic. The last holdout was Venice, which finally surrendered to the Austrians on 22 August after being stricken with damages and famine. With the fall of Venice, the First Italian War of Independence was over.

- Although the spirit of Risorgimento seemed to have been extinguished, the desire for greater freedom and national unification in Italy would continue to grow.

Image sources: