Download The French Revolution Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach The French Revolution to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Table of Contents

Add a header to begin generating the table of contents

Summary

- The long term and short term causes of the French Revolution

- Changes brought by Constituent Assembly, Legislative Assembly and the National Convention

- Political groups of the French Revolution

- The nature of the Reign of Terror

- The Directory and First Consul

- Impact of the revolution in France

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about the French Revolution!

- The French Revolution was a revolutionary event in modern European history. It began in 1789 and ended in the late 1790s when Napoleon Bonaparte ascended to power. The event redesigned their political landscape, abolishing an absolute monarch and their feudal system. Despite not achieving all its goals, the French Revolution played a significant part in shaping modern nations through the inherent will of the people.

Causes of the French Revolution

Influence of the Age of Enlightenment

- Between 1685 and 1815, Europe experienced drastic changes in politics, philosophy, and science. This period is often referred to as the Age of Reason, or simply the Enlightenment. Thinkers from France and Britain began to question traditional authority, which was the Catholic Church, on beliefs about the existence of humanity.

- Amidst the long existence of the Enlightenment before the outbreak of the French Revolution, historians suggest that it was one of the major causes of the revolution.

- The emergence of the ideas of liberty, equality, and individual rights, which overthrew the reign of King Louis XVI, was influenced by published writings of Enlightenment thinkers.

- Enlightenment thinkers and writers greatly influenced revolutionaries to question how feudal society and authority in France worked.

- Out of intellectual, political, and social desire for progress, thinkers in the 1600s until the 18th century challenged the existing body of knowledge explaining humanity and the natural world.

- During this period, the use of scientific process, reasoning, and logic saw traditional knowledge replaced with skepticism. Moreover, inventions and discoveries struck Europe. At the same time, European domination in Asia and Africa were intensified following exploration and colonisation of the Americas.

- In France, Enlightenment thinkers condemned censorship. Liberal thought, which focused on democratic values, spread.

- Aside from its effects on politics, the Enlightenment era created religious conflict in Europe.

Involvement in the American War of Independence

- The American War of Independence was a political battle that took place between 1765 and 1783 during which colonists in the thirteen American colonies rejected the British monarchy and aristocracy, overthrew the authority of Great Britain, and founded the United States of America.

- On February 6, 1778, France made an alliance with the American revolutionaries. Through the Treaty of Amity and Commerce and the Treaty of Alliance signed in Paris, France began to send fleets and armies.

- Years after the victory of the American colonists they assisted, the French faced their own political struggle. Scholars suggest that the American Revolutionary War set the stage for the French uprising.

- Why did France participate in the American Revolutionary War?

- France was Britain’s colonial rival. After the defeat in the Seven Years’ War, France wanted to restore its reputation.

- French participation and effects of the war

- Between 1778 and 1783, the French supplied the colonists with arms, munitions, and supplies. Moreover, a number of French troops and ships were sent to the colonies.

- In 1776, diplomat Benjamin Franklin was able to secure a formal alliance with France.

- In October 1777, after the colonists’ victory at the Battle of Saratoga, French King Louis XVI approved Franklin’s request for financial assistance.

- At the course of the American Revolution, about 12,000 French soldiers and 32,000 sailors, including Marquis de Lafayette, arrived in America.

- Scholars suggest that the French alliance and assistance were crucial in the British defeat at Yorktown.

- In 1780, the French led by commander Rochambeau landed at Rhode Island. In the same year, the Franco-American alliance marched south and besieged British General Charles Cornwallis at Yorktown.

- Due to the assistance provided, the French government faced a financial crisis, which led to political and social unrest in France.

- In 1783, the Treaty of Paris formally ended the war between the American colonists and their allies, France and Spain, against Britain.

- As a result of supporting the war effort financially, France faced a debt disaster and in order to resolve this, the government raised taxes and used loans to pay off debts.

- During the war, trade diminished and was only revived in 1783.

The Three Estates

- CLERGY - Known as Le Premier Etats, they were religious leaders that made up about 1% of the population. Members were exempted from paying any taxes.

- NOBILITY - Composed of nobility and the elite, Le Deuxième Etats were about 4% of the population. A member had to be born into the aristocracy and was exempted from most taxes.

- COMMONER - Consisted of the peasantry, Le Troisieme Etats was 95% of the French population, which included the working class who were taxpayers.

- Th estates of the realm under the Ancien Regime was characterised by the burden of taxation. The king was not part of any estates. Under feudalism, the peasantry, who were members of the Third Estate, produced food and paid heavy taxes.

- Both peasants and nobles were required to pay tithe, or one-tenth of their income, to the Church. On the other hand, the Church was obliged to pay the crown tax known as “free gift.” Prior to the French Revolution, members of the peasantry were required to pay land tax to the state and 5% property tax. Royal obligations were paid through labour, in kind, and in coin (rare). Moreover, peasant farmers paid their landlords in cash.

- In addition to the tax burden, people from the Third Estate were forbidden from holding petty positions in the regime. Both Kings Louis XV and XIV attempted to impose taxes on the First and Second Estates, but failed.

King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette

- Born as Louis-Auguste, Louis XVI was the last king of France before the end of the monarchy in the French Revolution. Married to Marie Antoinette, Archduchess of Austria, daughter of Holy Roman Emperor Francis I, Louis XVI (and his wife) were convicted of high treason and were executed by guillotine on October 16, 1793.

- At the time of King Louis XVI, absolute monarchy ruled France. Monarchs enjoyed unlimited power and viewed themselves as representatives of God. With such high regard for themselves, many French monarchs, including Louis XVI and his wife, lived in luxury and extravagance in Versailles.

- By the time of Louis XVI’s ascension to the throne, France was under serious economic crisis. In 1774, the king appointed Turgot as finance minister. Expenditure of the royal court was reduced and more taxes were imposed. By 1776, Necker replaced Turgot and he published a report on the income and expenditure of the state.

- In 1783, Callone became the finance minister. He adapted the borrowing policy to compensate for the expenditure of the royal court, which resulted in huge national debt.

- When Louis XVI made an alliance with the American colonists during the American Revolution, he brought France to the verge of bankruptcy. Imposition of new taxes to cover national debt deeply enraged people in France, especially the members of the Third Estate. Moreover, when the price of bread reached its height, Louis XVI implemented deregulation of the grain market, which caused famine.

- On August 8, 1788, the king summoned the Estates-General in an attempt to solve the financial crisis.

- Absolute monarchy is a form of government in which a society is completely ruled by one monarch.

Assembly of Notables (1787)

- Due to extravagant spending of the royal court, insufficient revenue, and national debt, France experienced fiscal crisis and went on the brink of bankruptcy. In response, with the advice of financial advisor Charles Alexandre de Calonne, King Louis XVI called upon the Assembly of Notables.

- In February 1787, about 144 members composed of nobles, bishops, magistrates, deputies, and mayors gathered at Versailles and convened the Assembly of Notables. Calonne requested Louis XVI to convene the assembly to pass fiscal reforms without the debate of the parlement.

- Similar to the Estates-General, the Assembly of Notables was an ancient institution in France that was rarely used. At the king’s order, a council composed of clergymen and nobles formed an assembly to respond during a time of crisis and be the crown’s adviser. About three assemblies (1583, 1596, 1626) prior to 1787 were convened under a king’s order.

- The Assembly of Notables, as its name indicates, was a council composed of members from the First and Second Estates.

- The French parlement was then composed of high courts that often reject tax reforms as they would negatively affect them.

Policies of Calonne and Brienne

- Amidst having no independent legislative power, Calonne sought the formation of the Assembly of Notables in 1787 to put pressure on the parlement and support his fiscal reforms. However, members of the Notables did not support Calonne’s reform package. The assembly believed that any major reforms that would greatly affect the Three Estates should be approved by the Estates- General.

- Unitary land tax

- In contrast to vingtiémes, the new single land tax would be payable in kind, thus making it free from inflation. Moreover, it would affect all landowners regardless of social rank. Assessment would be according to property value and collection to be supervised by local intendant.

- Commutation of the corvée

- Corvée was a form of forced labour on public highways, which he proposed to be converted to monetary contribution to be spent in diverted purpose.

- Vingtiéme was a form of income tax in which nobles were usually exempted.

- Four major fiscal reforms proposed by Calonne

- Election of provincial assemblies

- Similar to Turgot, Calonne sought democratic reforms to free the provinces from corruption and buying of positions by the elite class.

- Abolition of internal tariff

- Calonne proposed complete freedom of grain trade and temporary suspension of export. Moreover, he suggested fairer tax collection through proportional taxation that did not exempt the elite.

- The formation of the Assembly of Notables did not help Calonne with his fiscal proposals. As another measure, he sought public support through publication of the French fiscal problems and his attempts to solve it.

- As a result, the public knew about the nation’s deficit of 110 million livres. By April 7, 1787, Calonne was dismissed by both the Notables and King Louis XVI and immediately replaced by Loménie de Brienne, Bishop of Toulouse.

- Like Calonne, Brienne pushed for the same fiscal policies. The difference they made, Brienne was a favourite of Marie Antoinette which made him an influential figure in the royal court. Moreover, he was a member of the Assembly of Notables prior to his appointment as fiscal director.

The Estates General (1789)

- États Généraux in French, the Estates General was a form of representative assembly similar to a congress or parliament. Members were representatives from all the Three Estates. Different to congress or parliament, French Estates General had no legislative power and did not meet regularly. Meetings were only held as summoned by the king, mostly in times of crisis or war.

- Ahead by three years, Louis XVI summoned the Estates General on August 8, 1788, after the notorious ‘Day of Tiles.’

- Both following Turgotian policies, Calonne and Brienne had very few fiscal reforms. Brienne proposed to increase tax contributions from the Church, however, both the parlements and the Assembly of Notables rejected the idea of imposing new land tax to the members of the First and Second Estate.

- With Brienne’s further attempts to impose Calonne’s reforms, he developed conflict with the parlements who insisted that only the Estates-General had the right and power to tax.

- In 1787, as Brienne proposed his fiscal reforms which included new taxes, the Paris parlement disagreed and demanded that the Three Estates combined had the power to approve such taxes. Tensions increased and triggered an eight-month conflict between the royal government and the parlements. In late 1787, in order to win over the Paris parlement, Louis XVI promised to convene the Estates General for 1792.

- Traditional voting procedure and composition of Estates General

- Traditionally, members of the assembly voted by order through each of the Three Estates separately before casting one vote. Through this process, the Third Estate, composed of commoners and majority of the French populace, was regularly outvoted by the two higher estates.

- In September 1788, the Paris parlement issued an edict for the Estates General to adopt the 1614 form and procedure, which condemned members of the parlements as servants of aristocrats.

- Louis XVI issued another edict for the instructions of electing deputies to the Estates General on January 24, 1789. For the First and Second Estate, deputies were elected through an electoral assembly which was attended by all clergymen and nobles.

- Composition of Estates General deputies

- Due to expensive travel and stay in Versailles, where the Estates General convened, deputies should be wealthy. As a result of this limitation, deputies of the Third Estate were mostly representatives of the bourgeoisie, not the working class.

- No peasants or artisans were elected as deputies. About 80 of them were business owners, while half were practicing lawyers.

- About 208 of the 296 deputies of the First Estate were parish priests, while the remaining number were bishops.

- About 70% of deputies from the Second Estate were serving or retired military officers. The remainder were aristocrats.

The Tennis Court Oath

- With long lists of grievances, hopes of political reforms, and expectations of being outvoted, the Third Estate declared itself the National Assembly on June 17, and took oath at a tennis court on June 20, 1789 to force King Louis XVI for a new constitution.

- By locking the hall, the Third Estate was excluded from the regular meeting. In response, they gathered in an indoor tennis court where they took oath.

Storming of the Bastille

- The Bastille served as a prison of political dissidents, including writers and philosophers. Today, the violent storming of the Bastille on July 14, 1789 is commemorated every year to remember the tyranny of the French monarchs, Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette.

- The Bastille was a military fortress built during the Hundred Years’ War in the 1300s to protect the eastern entrance of Paris against the English.

- Following their demands to increase voice in governance, members of the Third Estate worried that the French army would soon attack them. In hopes to arm themselves, Parisian revolutionaries took over the Hotel des Invalides in Paris where they seized muskets.

- At that time, aside from being a prison, Bastille was a military fortress filled with gunpowder and munitions. On July 14, the revolutionaries demanded that Governor de Launay of Bastille surrender, abandon the gunpowder, and free the prisoner. Launay initially refused.

- In the process of negotiations, the crowd became aggressive, Bastille was surrounded, fighting began, and the French soldiers soon sided with the revolutionaries.

- As more Parisians converged in Bastille, Launay raised a white flag. Along with few of his officers, he was taken at the Hotel de Ville and tried by a revolutionary council. However, he was pulled by a mob and killed.

- Generally, the event bolstered the political significance of the revolution. It demonstrated how the common French people wanted to end tyranny and feudalism.

Grande Peur

- Known as the Great Fear, a series of peasant riots occurred between July and August 1789 after rumours of brigands or outsiders rampaging the countryside. Rumours of violence invoked various responses from the peasantry.

- Many peasants responded to the rumours by:

- Arming themselves to defend their property from raids

- Looting chateaux of aristocrats

- Neglect and destroy of feudal contracts

- With such acts, the peasants became the brigands they had initially feared.

- Why did the peasants respond that way?

- When France suffered a food crisis in the spring of 1789, many peasants developed paranoia towards arriving outsiders. Most outsiders who traveled in the middle of the year were landless labourers, beggars, and vagrants. Peasants in the countryside feared that they were competitors for scarce labour, food, and charity.

- Moreover, peasant communities believed that the king hired brigands to suppress growing revolutionary sentiments in the countryside.

- During the Grande Peur, large groups of armed peasants searched for targets in villages. Targets were symbols of feudal authority, including contracts, obligations, land holdings, and private property. The seigneurs or landed aristocrats suffered worse.

- In late July, riots in Dauphine, in south-eastern France, were considered as the worst of the Great Fear. Peasants who formed gangs ransacked and burned many chateaux. Only those aristocrats who tried to resist were harmed. Some who refused to renounce their feudal rights were held for ransom.

- In response, some nobles gathered and established their own militia to protect their citizens, similar to the act of Baron de Drouhet and Baron de Belinay of Limousin.

- With unclear reasons behind the panic, scholars continued to research on its cause. In the late 1980s, Mary Matossian theorised that the riotous peasants may have eaten ergot contaminated wheat, which caused paranoid delusions.

The National Assembly

- Formally known as the National Constituent Assembly (Assemblée Nationale Constituante), the French National Assembly was formed in June 17, 1789 by delegates from the Third Estate as they split from the Estates General. Angered by their unheard voice in the government, the Third Estate delegates met and took oath in a nearby tennis court.

- With principles of establishing a new constitution, they formed the National Assembly, a new revolutionary government that lasted until 1791.

- As resentment towards King Louis XVI spread, a number of delegates from the First and Second Estates joined the National Assembly. By July 9th, the National Assembly formed into the National Constituent Assembly and remained until replaced by the Legislative Assembly in 1791.

- Following the storming of the Bastille, the National Assembly began to rule France in order. Forces of the Assembly, the conservatives (The Right), and the Monarchists (The Left) emerged.

Changes brought by the Constituent Assembly

- On July 9, 1789, the National Constituent Assembly, simply known as the Assembly became the new governing body of France. Originally, delegates from the Third Estate comprised the assembly and were later on joined by representatives from the First and Second Estates, mostly composed of clergymen and nobles.

- A number of special privileges among nobles were abolished, including hereditary titles of prince, baron, and duke.

- Under the Civil Constitution of the Clergy, the local people got to elect churchmen who were then paid by the state.

- Most church estates were sold to bidders. A few low cost lands were sold to peasants; the majority were bought by wealthy people.

- New paper money called assignats was introduced. However, due to continued financial crisis, it quickly lost its value.

- The most significant accomplishment of the Assembly was the abolition of feudalism, serfdom, and class privileges, which were the reasons behind peasant attacks against the nobilities.

- On August 27, the National Assembly passed the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizens that became a written document of Rousseau’s philosophy on natural rights - freedom and equality.

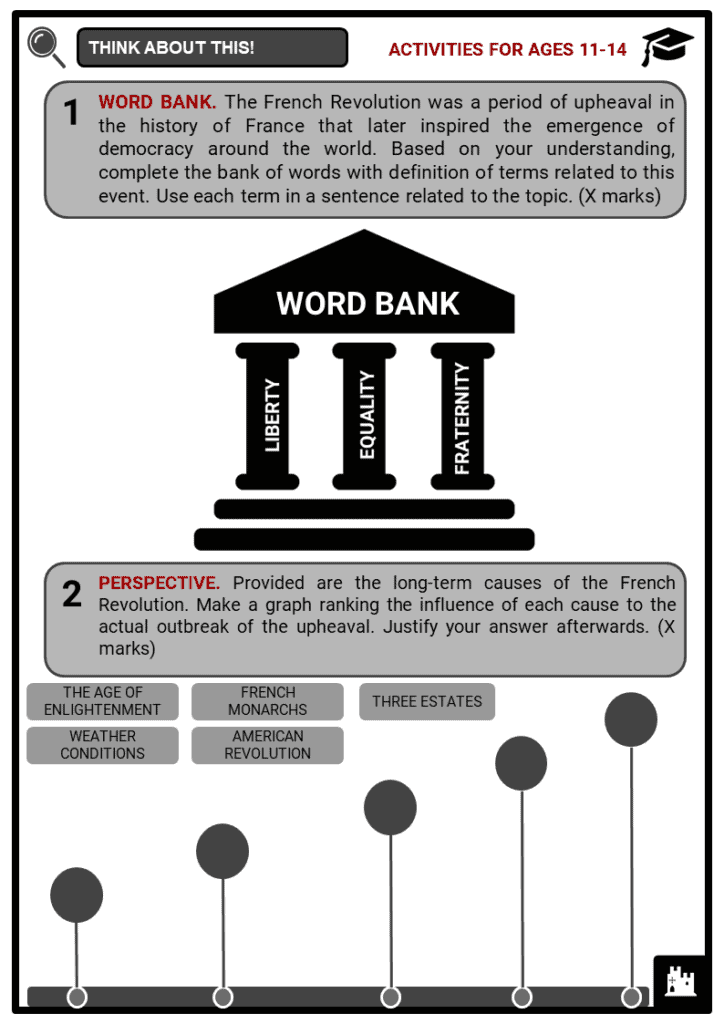

Groups of the French Revolution

- SANS CULOTTES

- The Sans Culottes was one of the many groups that drove the French Revolution. They were generally members of the lower middle-class, including apprentices, craftsmen, shopkeepers, and clerks. Given their number in Paris and provincial cities, the Sans Culottes were the strongest group in Paris. Willing to commit violence, they gathered a massive street army.

- The term Sans Culottes literally means ‘without.’ A culottes was a form of high knee clothing wore by members of the wealthy class.

- The Sans Culottes specifically aimed to achieve justice and equality. They demanded jobs and price fixing. Moreover, they were significant figures in implementing Terror, which condemned numerous aristocrats. However, their freeing goal of equality was immediately turned into a force of violence.

- Most of them were responsible for the storming of the Bastille and murder of its governor. In October 1789, sans culottes women participated in the march on Versailles that demanded the return of the royal family to Paris.

- Sans Culottes in Paris took over the Tuileries palace in August 1792. On the same day, they were also able to coerced the Legislative Assembly to suspend the monarchy.

- In September 1792, they raided a number of prisons in Paris and murdered counter-revolutionaries. Aside from their clothing and violent acts, historians characterised members of the San Culottes as class warriors and the backbone of the revolution.

- GIRONDINS

- Also called Brissotin, the Girondins was a group of republican politicians from the department of the Gironde of the Legislative Assembly. They were initially composed of lawyers, journalists, and intellectuals, and later joined by merchants and industrialists.

- Both Girondins and Jacobins fought in the French Revolution. Amidst their radical ideologies, the Girondins were labeled as the conservatives, while the Jacobins were called as the republicans.

- JACOBINS

- The Jacobins were radical revolutionaries who plotted the execution of King Louis XVI and establishment of the French Republic. They were known as the Initiator of Terror during the French Revolution. The Jacobins believed that all powers and rights resided in the people. In contrast to absolute monarchy, Jacobins proposed that the people were the true supervisor of their leaders.

- Members of the Jacobins included delegates from the elite class, artisans, and tradesmen. Among them was leader, Maximilien Robespierre, who infamously led the Reign of Terror.

- In 1792, the Jacobins stormed the Tuileries palace and seized the French royal family. In September of the same year, they led the abolition of monarchy and declaration of France as a Republic.

- Formally known as the Society of the Friends of the Constitution, the Jacobin Club was established in August 1789 and identified with the ideas of egalitarianism.

- The Reign of Terror in 1793 was characterised by intense violence involving execution of counter-revolutionaries through guillotine. Thousands of them were killed without trial or died in jail. Members of the Jacobins lived with the motto “Live free or die.”

The Legislative Assembly (1791-920 and the National Convention (1792)

- In October 1791, the Legislative Assembly replaced the National Constituent Assembly of France. Its members were elected a month before which included deputies who had record in public service either at provincial or municipal level. Many were new delegates were members of the Jacobin Club.

- Power of King Louis XVI over the Assembly

- Appointment of ministers

- Power of suspensive veto

- Given his power, the Legislative Assembly faced challenges and problems. The king appointed ministers based on his alliances and not of merit. Moreover, he used his veto power to block legislations. As a result of numerous royal veto, public protests against the monarch became uncontrollable.

- There were about 330 republican deputies, 165 constitutional monarchists, and 250 politically non aligned delegates.

- The Assembly also failed to solve French economic crisis. With ineffective constitutional monarchy, the Legislative Assembly struggled to pass reforms. Moreover, their involvement in external war worsened their financial status.

- In August 1792, the Assembly concluded that Frenchmen aged 21 above, a resident for a year with decent job had the right to vote in the national elections for a new legislature. The right to suffrage was not universal, it was denied to servants and women.

- In the first week of September 1792, the elections for the new National Convention was conducted. About 749 deputies with varied political affiliations were elected to the Convention.

- The Convention was formed after the storming of the Tuileries and suspension of the monarchy. The Legislative Assembly took over governance and functioned as the head of state.

- They captivated public support by replacing the ministers with more popular figures close to the people. Amidst the reforms provided by the Assembly, divided deputies led to the demise of the chamber.

- A total of 749 deputies of different political affiliations were elected by around a million abled Frenchmen over 21. On the second session, the Convention;s deputies passed the abolition of monarchy and turned France into a republic.

- As months passed by, the Convention was divided into factions. The Montagnards who occupied the upper seats to the left of the president were known radical democrats. Opposite to them were the Girondins, characterised as moderate republicans led by Jacques Brissot. Initially, most proceedings were dominated by the Girondins as they were manned with orators and lawmakers.

The Edict of Fraternity

- On November 19, 1792, the National Convention issued the Edict of Fraternity, which stated that the French were friends of the people, while all governments were their enemies. The Edict persuaded European people to rise against their respective monarchies and seek freedom to govern. It also promised material and moral support to those who would lead the uprisings.

- The French wanted to spread republicanism as a form of government replacing absolute monarchy. Through the revolutionary ideas of liberty, equality, and fraternity they believed to wipe out the ills common to societies governed by monarchs.

- As a result, most monarchical governments in Europe feared that the French revolutionary causes would spread and dethrone them. This fear destroyed the possible co-existence of France with the rest of Europe.

- With the possible dangers of the Edict of Fraternity, plus the the French expansion of its natural frontiers, the British condemned the French plans due to potential threat to their trade and security.

The trial and execution of King Louis XVI

- Deposed King Louis XVI was formally placed on trial by the National Convention in December 1792. Louis XVI was read with 33 charges that describe an act of betrayal and failure of leadership. After gaining 693 votes from the National Convention, the king was found guilty and sentenced to execution without any right for an appeal.

- Even prior to the trial, King Louis XVI’s fate was already decided after the August 10 storming of the Tuileries, when the royal family took refuge in the chamber of the Legislative Assembly, while the crowd was demanding for the abolition of the monarchy.

- With public demand, the Legislative Assembly ordered the suspension and arrest of Louis XVI. He and his family were stripped of royal and noble titles and rights amidst the existing Constitution of 1791.

- Initially, the National Convention spent almost a month debating on whether “Louis XVI ‘judgeable’ for the crimes he is imputed to have committed on the constitutional throne?”

- After presentation of arguments, the National Convention agreed that Louis XVI should be put on trial on December. After a week, the former king gathered the best French lawyers, including Raymond de Sèze, Francois Tronchet, and Guillaume Malesherbes to defend him.

- Louis XVI’s Defence

- Under the former king’s instruction, his lawyers questioned the legality of the trial under the existing constitution.

- The defence refuted the claims that the king was to blame for foreign aggression, military failures, and storming at the Tuileries.

- After short deliberation of the arguments, the National Convention voted and handed down a guilty verdict on January 15, 1793. Along with the crowd, mostly Parisian sections, and the Jacobins inside the Convention, they called for the king’s execution. On January 17, with 424 votes against 283, the Jacobins and the Plains defeated the motion of an appel au peuple, while 387 to 334 votes favoured Louis XVI’s execution.

- On January 20, the king’s death warrant was finalised by the Convention. The order also stated that his execution should be done within 24 hours.

- In response, Louis XVI appealed for three days to bid farewell to his family. On the evening of January 20, he was allowed to visit Marie Antoinette and their children, but the other request was rejected.

- The next day, a non-juring priest officiated a mass. He rode a carriage traversing the streets to Paris. By 10 o’clock in the morning, he arrived at the former Place de Louis XV.

- An estimated 100,000 people gathered in the square to witness the king’s execution.

- The executioner tied Louis XVI’s hand and then cut his hair. His body and head were taken to the parish cemetery and thrown into a pit.

- In London, the French king’s execution was seen as a descent of anarchy and act of regicide. They expelled the French ambassador, four days after Louis’ death. In response, France declared war against England. In Russia, Catherine the Great broke its relation with France, while Austria and Prussia heightened its war against them.

The Reign of Terror

- Between September 1793 and July 1794, the Committee of Public Safety ruled over France during the Reign of Terror. On April 6, 1793, this political body was formed while France was under the threat of foreign and civil war.

- Ideally, the committee was formed to secure the nation’s defense against foreign and domestic enemies. Moreover, it was designed to oversee the ruling of the executive government. Members were elected by the National Convention. By July, after the failure of the first set of committee, radical delegates replaced them, including Maximilien Robespierre.

- The Committee of Public Safety was able to dominate the national Convention through the support of the Jacobins. They implemented the following:

- Counter-revolutionaries were hunted down

- France turned into a war economy

- Mass conscription was imposed

- Despite the limitations provided, the Committee was dominated by radicals which resulted to dictatorship of the National Convention, instead of acting on its behalf. The CPS held secrecy and autonomy.

- Initially the Committee contained 9 seats, later extended to 10, then 12, which were replaced every month to prevent individuals from gaining excessive power.

- On December 4, 1793, the National convention passed the Law of 14 Frimaire that formalised the political power of the CPS. The law was later dubbed as the ‘Constitution of the Terror.’

- Unlike the Montagnards who supported the execution of Louis XVI, the Girondins believed that the penalty of death should be endorsed by the people. In addition to losing in the Convention’s vote, Parisian radicals labeled them as royalist sympathisers.

- In addition to conflict against the radicals of Paris, the Girondins’ investigation of the Paris Commune, and the arrest and murder of Jean-Paul Marat decreased their popularity.

- In December 1792, Girondin deputies lobbied for an ‘appeal to the people’ on whether the former king should be executed.

- The Girondins failed to effectively respond to the economic crisis in Paris. On the other hand, the Jacobins and their allies were able to establish a dictatorship.

- The Montagnards sought the support of the sans culottes which finally resulted in the expulsion of Girondin deputies from the national Convention on June 2, 1793. As a result, the radical gained full control of the Convention.

- The power struggle between the Jacobins and Girondins escalated after the king’s execution. Led by Robespierre, the Jacobins were able to exclude the Girondins and dominate the Convention and later the Committee of Public Safety.

- As an influential member of the CPS, Robespierre orchestrated the ‘Reign of Terror,’ which eliminated counter-revolutionaries. Also, initiated by him, the cult of the Supreme Being, a new official religion was introduced in France. For 11 months, about 300,000 alleged enemies were arrested, while an estimated 17,000 were executed, dominantly through guillotine.

- When the Jacobins led by Robespierre took dominant control of the National Convention and the CPS in June 1793, administrative and political purges were called. The Jacobins supported by the sans culottes were radicals who saw violence as a way of insisting on their political goals and rights.

Impact of the Reign of Terror

- Violence and terror became an official and legal government policy. Amidst keeping record of death sentences, many were executed without being tried in court. Thousands of condemned counter-revolutionaries were put to death by guillotine. Some were beaten to death by mobs and angry crowd.

- Under the implementation of the Law of Suspects, prison population increased to 4,525 people from 1,417 within three months.

- As a direct effect of political instability, France, especially Paris, suffered inflation, unemployment, and starvation as industries were damaged.

- Prior to introduction in France, the guillotine was used in Scotland and England to execute aristocrats.

- Introduced in France in 1792, the guillotine was a capital punishment by decapitation using a crossbeam and an oblique-edged knife that sliced through the neck of a person.

- In 1793, fearing the spread of revolutionary ideas, nations like Britain and Russia formed a coalition against France. Moreover, in order to safeguard their rule, many European monarchs became despotic.

- The Reign of Terror led to the death of many senior military officials, which opened political space to young Napoleon Bonaparte.

- The fear of death by guillotine led many nobles and clerics to either flee to neighbouring nations of Austria and Prussia, where they became emigres or engage in self exile.

- In 1795, the Directory Government was formed to resolve the social, economic, and political damaged caused by the Reign of Terror.

- This period in French history marked the end of the Bourbon dynasty and the beginning of republicanism.

The Directory and First Consul

- Following the end of the National Convention, the French Directory was formed under the Constitution of 1795. It lasted until November 1799 with the emergence of Napoleon Bonaparte.

- Structure of the Directory

- The Directory was composed of 5 directors (at least 40 years old) who exercised executive power and were appointed by the Legislature.

- Council of Ancients - Composed of 250 members (at least 40 years old) who voted on laws and were selected from 750 electors.

- Council of 500 - Large property owners (at least 30 years old) who proposed laws.

- Over the years of the French Revolution, the Directory was the last among the four revolutionary governments; National Assembly, Legislative Assembly, and the National Convention.

- The Directory was created to abolish dictatorship during the Reign of Terror, but later gave way to another dictatorship led by Napoleon Bonaparte.

- The first elected members of the Directory included Paul Francois Jean Nicolas, Louis Maries de La Revelliere-LePeaux, Jean-Francois Rewbell, Etienne-François Le Tourneur, and Lazare Nicolas Marguerite Carnot.

- Factors for the fall of the Directory

- When Napoleon returned from his expedition in Egypt, the French people revered him as a hero. He made an alliance with a number of influential politicians to overthrow the Directory through a coup d’état on November 9, 1799, also known as the Coup of 18th Brumaire, based on the revolutionary calendar.

- With ongoing war with Austria, and military campaigns of Napoleon in Egypt and Syria, the French economy suffered. The Directory was left with only Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès after the ousting of the Jacobins by the Coup of 30 Prairial.

- Other than Carnot, all Directors were corrupt and greedy, focusing on personal gains rather than the national interest of France.

- With the inefficiency of the Directory, the French people got tired of revolution. Instead of fighting in the streets again, they fixed their sights on Napoleon whom they expected to solve both the domestic and foreign problems of France.

- Instead of addressing the problems of the French people, the Directory focused on maintaining its structure and power.

- Between 1804 and 1814, Napoleon Bonaparte, or Napoleon I, served as the emperor of France, and again in 1815. He was a skilled military and political leader who gained prominence during the French Revolution and the Revolutionary Wars.

- Bonaparte’s first stint in the military was in 1789 during the outbreak of the revolution. A Corsican nationalist, Bonaparte supported the Jacobin movement.

- In 1792, he was promoted to captain. At the age of 24, he was promoted to brigadier general and was put in charge of the French artillery in Italy by the Committee of Public Safety.

- Amidst his close relations with Robespierre, who was then lined up for execution, Bonaparte was released from prison and tasked to draw up plans for France against Austria.

- Bonaparte gained enormous fame from the Directory and the rest of France when he subdued the royalist coup of 18 Fructidor. He was promoted to Commander of the Interior and took command of the French army in Italy.

- In his campaigns, Napoleon successfully invaded Italy and defeated the Austrian army. After his failed conquest of Egypt, Napoleon returned to France, still a hero. He initiated a coup within a coup; Sieyès initially planned with him.

- Napoleon stormed into the legislative chambers and used his military power to put the deputies under pressure. Initially, the deputies resisted, but were forced to succumbed to Napoleon’s demands.

- With the fall of the Directory, the plotters convened two commissions, both with 25 deputies from the Councils. The commissions then declared a provisional government with Napoleon, Sieyès, and Ducos as Consuls. Immediately, Sieyès influenced the commissions to draw up a new constitution. After two months, new consuls replaced Sieyès and Ducos, until Napoleon consolidated his own authority as the First Consul outpowering the other consuls and Councils.

Achievements of the revolution in France (1789-1799)

- The French Revolution lasted for ten chaotic years (between 1789 and 1799) and altered not only Europe’s course, but world history in general.

- Feudalism was abolished. Peasants acquired land and property that used to be under possession of nobles and clergy only.

- Monarchy as a form of government was dissolved. From absolute monarchy, the revolution introduced the constitution, and then the republic, which triggered weakening of other monarchical governments in Europe.

- It spread the spirit of liberalism in Europe and ignited an age of revolutions. By the turn of the century, one by one, absolute monarchies were overthrown by revolutions.

- Introduction of the principles of equality and freedom. Revolutionary France was the first state to grant universal male suffrage. The revolution was based on the Enlightenment ideas of liberty, freedom, and fraternity.

Image sources:

[1.] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/15/Antoine-Fran%C3%A7ois_Callet._PORTRAIT_OF_KING_LOUIS_XVI_IN_FULL_CORONATION_REGALIA.jpg

[2.] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/e2/The_burning_of_the_royal_carriage_during_the_French_revolution_of_1848.jpg

[3.] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Tennis_Court_Oath_(David)#/media/File:Serment_du_Jeu_de_Paume_-_Jacques-Louis_David.jpg