Download Public Health During the Industrial Revolution Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach Public Health During the Industrial Revolution to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Table of Contents

Add a header to begin generating the table of contents

Summary

- A brief background of the Industrial Revolution in Britain

- Public health in Britain through time

- Public health during the Industrial Revolution, including issues, discoveries and innovations.

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about public health during the Industrial Revolution!

- The Industrial Revolution, also today referred to as the First Industrial Revolution, can be defined as a series of transitions towards new manufacturing processes in Europe and the United States. These transitions, which entailed changing from hand production to using machines, occurred from the 1760s until the mid-19th century.

- The revolution majorly affected a whole series of industries, especially textiles, iron, and transportation, but also agriculture, mining, chemicals, agriculture, and steam power.

- As the Industrial Revolution mainly began in Great Britain, the leading commercial power in the 18th century, its most profound effects were first felt on the isles.

- While population numbers did grow exponentially in the late 18th and 19th centuries, it was difficult for even rapid industrialising processes to keep up with the increases in demand for food and housing.

- Many, therefore, argue that those at the very bottom of the economic ladder suffered from the Industrial Revolution until at least the 20th century.

- For this reason, it was in the 19th century that Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels wrote The Communist Manifesto noting the poor conditions of the working class.

- However, the Industrial Revolution was certainly not all bad in terms of social effects – thanks to these processes, British society improved significantly in terms of literacy and education.

- The revolution also, in the eyes of many, created the conditions for the emancipation of women as well as urbanised societies, bringing hundreds of thousands of people from villages to cities.

Historical background of public health in Britain

Medicine in Medieval Britain

- The medieval and early modern era in Britain faced serious challenges when it came to protecting individuals, communities and populations from disease. These included: (a) a society with a high number of peasants who could not afford to see doctors and relied on monasteries for medical help, (b) famine which increased levels of crime, disease, mass death, and even cannibalism and infanticide, (c) war, (d) and poor knowledge of disease, sanitation, and safety.

- TOWNS Dark, poorly ventilated streets were common. No plumbing meant chamber pots were thrown onto the street along with kitchen waste. Livestock roamed freely in town and manure was left to rot. An average town of 150- 2000 people produced a lot of waste!

- HOUSES in towns and villages were made from wood, clay and brick with tiled or straw roofs. Floors were lined with hay for warmth and to absorb liquids. Houses were damp, dark and poorly ventilated. They attracted rats, mice, lice and fleas, and mould grew easily.

- HYGIENE Most people washed very infrequently. Christian beliefs of earthly life being preparation for heaven lead to ideas that bathing was an earthly indulgence to be avoided. Clean water was rare, making it dangerous to drink and to prepare food with.

- Because there was no real scientific approach to identifying the causes of illness, four primary theories dominated the Middle Ages...

- Supernatural reasons - Astrology was big in the medieval era. Doctors used almanacks to determine the influence of the stars on organs and illness.

- Theory of the four humours - Four fluids, namely blood, yellow and black bile and phlegm needed to be in balance, otherwise illness would strike. E.g. bloodletting (see resource on medieval medicine).

- Religious reasons - Most people were illiterate and relied on the church for info. Powerful and strict, the church linked illness to sin, punishment by God or the work of the devil and demons.

- Miasma Theory - The idea that bad air or bad smells were to blame for illness. They had yet to connect that smells of rot or filth were linked to bacteria and disease-carrying pests.

Medicine in Renaissance Britain

- The Renaissance was a period in European history between the 14th and 17th centuries and marked the transition from the middle ages to modernity. It arrived in England in the 16th century after the War of the Roses ended and reached its height in the Elizabethan age. It influenced medicine in the following ways...

- The invention of the movable type printing press in the late 15th century meant that ideas and knowledge could be spread to a wider audience and much more quickly. As more people learned to read, educational reform began, too.

- Artists and physicians mutually benefited from collaborations. Artists wanted to create more natural and anatomically correct bodies, so they observed dissections, while physicians needed artists to accurately draw their findings from dissections.

- The Renaissance saw the rediscovery of classical Greek philosophy, which brought about new thinking in the arts, architecture, politics, science and medicine. After the Black Death, new ideas and more knowledge were needed in medicine.

- New ideas challenged the Church’s grip on power and knowledge. Scholars questioned doctrines and began seeking more scientific and evidence-based answers to questions that ordinarily the Church answered in accordance with the Bible.

Events that changed medicine

- Henry VIII, Elizabeth I and other governments were strong and rich. With a booming economy, prosperity rose and ordinary tradesmen could afford to use a doctor.

- The discovery of the New World saw Columbus and other explorers bring back different knowledge and new kinds of food and medicine.

- Artists wanted to study the body to create more natural works. By studying the body and drawing it in detail, knowledge of anatomy improved.

- Learning was revived with universities creating schools of medicine. Scientific methods of experimenting, collecting data and recording observations emerged. This led to questioning ancient Greek and Roman teachings.

- Many new inventions were used for battle. The arrival of gunpowder, for example, saw soldiers getting new injuries that doctors needed to learn how to treat.

- Gutenberg’s printing press allowed new ideas to spread more quickly.

Medicine in Industrialised Britain

- The Industrial Revolution had a profoundly transformative effect on public health. Overall, it has been concluded that while the Industrial Revolution brought with it a lot of widespread health issues, it also led to major improvements in public health and facilitated the formation of the basis of what we today call public healthcare.

Factors that influenced 19th-century medicine

- URBANISATION

- England was becoming increasingly industrialised, which saw the rapid growth of towns comprised of crowded and poor housing, little sanitation infrastructure and dirty water supplies. Diseases such as tuberculosis, typhoid and cholera spread quickly.

- Life in towns and cities

- Some suburbs predated the Great Fire of 1666.

- Passages and alleys were haphazard.

- Some houses consisted of just two rooms with no

- through ventilation.

- Toilets were cesspits shared with neighbours, so some preferred to use the streets.

- Water was drawn from a common standpipe.

- Personal and home hygiene was poor.

- TECHNOLOGICAL ADVANCEMENT

- In steel and glass meant better syringes with thinner needles could be manufactured, and more sophisticated microscope lenses could be made. The first thermometer was made in the

19th century.

- In steel and glass meant better syringes with thinner needles could be manufactured, and more sophisticated microscope lenses could be made. The first thermometer was made in the

- IMPACT OF WAR

- The Crimean war (1853-56) experienced mass casualties (around 700 000 deaths). This necessitated improvements in the standards of nursing and hospitals.

- SCIENTIFIC MEDICINE

- Scientists had finally made the link between microbes and disease, and chemists had found a way to use particular gasses as anaesthetic.

- BETTER COMMUNICATION

- Industrialised printing meant more books and newspapers. It resulted in the following:

- Literacy rates improved with more and more reading material available.

- More people had access to information, including public health warnings, news and treatment developments.

- Conferences and events could be organised, giving people opportunity to share and debate knowledge.

- Industrialised printing meant more books and newspapers. It resulted in the following:

Public Health Issues

- Spread of Epidemics

- The key public health issues during the industrial revolution included widespread epidemics of infectious diseases like cholera, typhoid, typhus, smallpox, and tuberculosis. These can all be traced back to overpopulated cities, poor housing and living conditions, mass pollution and a lack of a public infrastructure to care for the citizenry’s health.

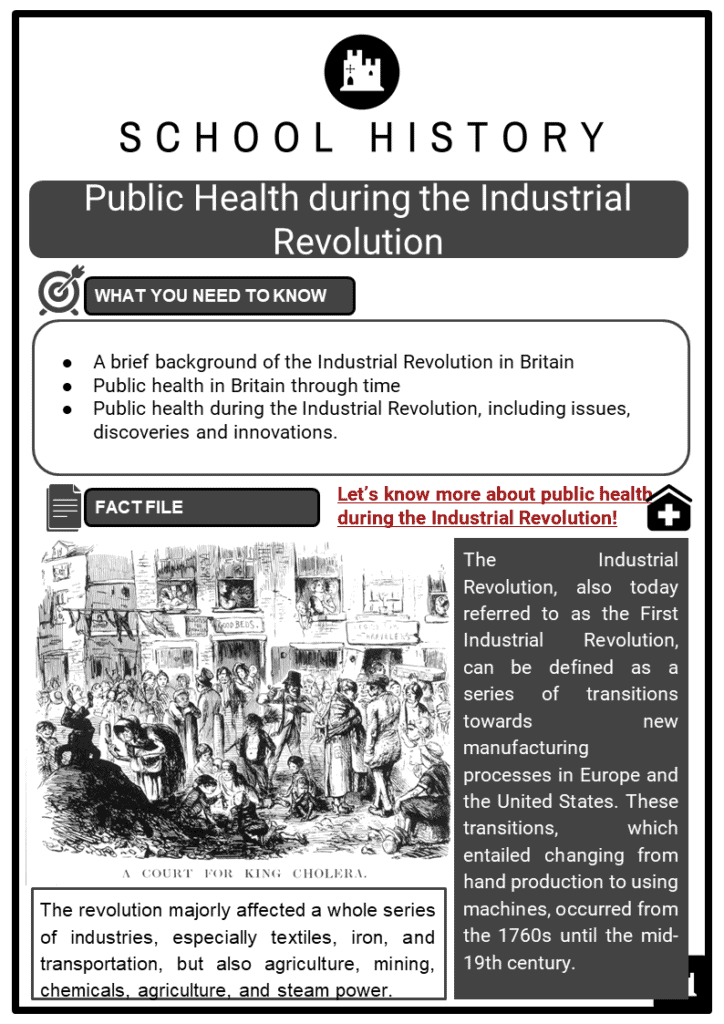

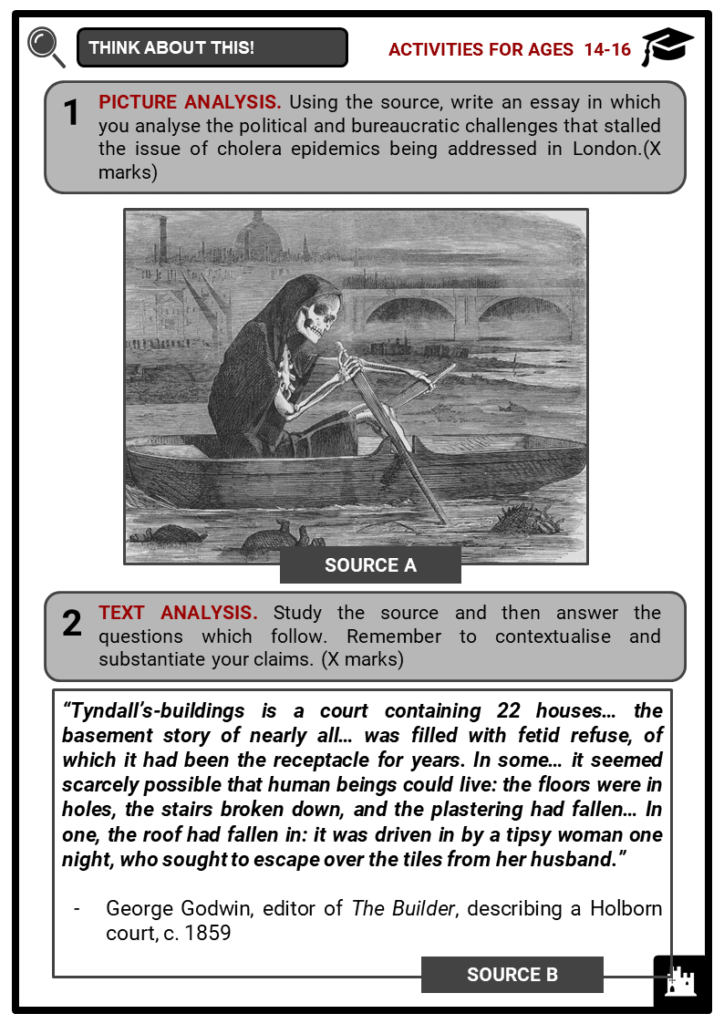

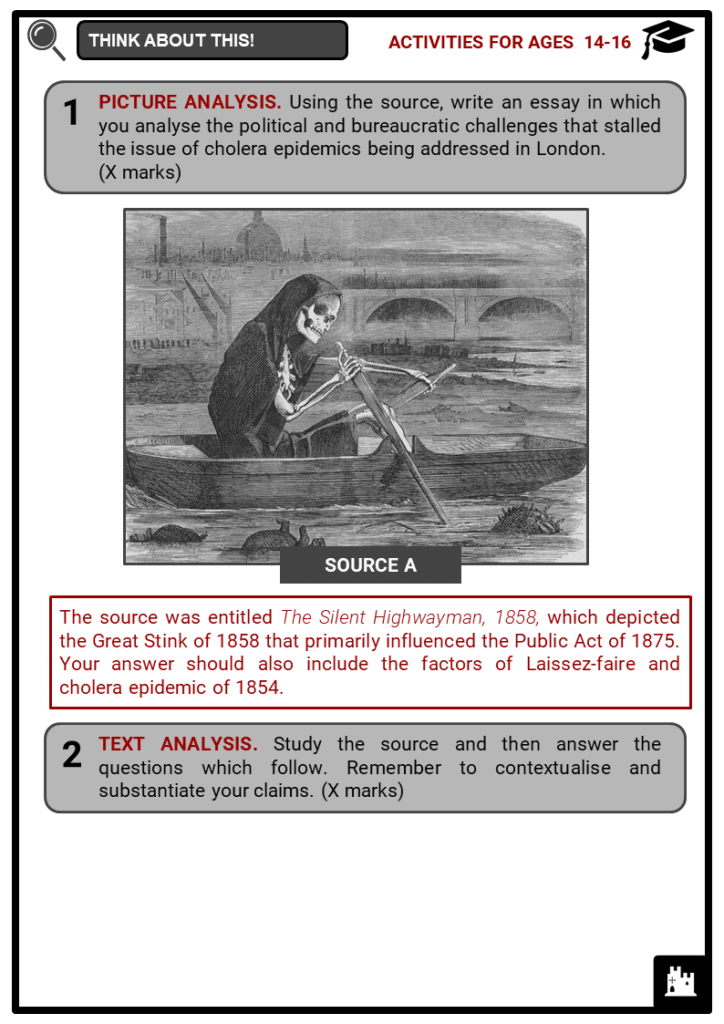

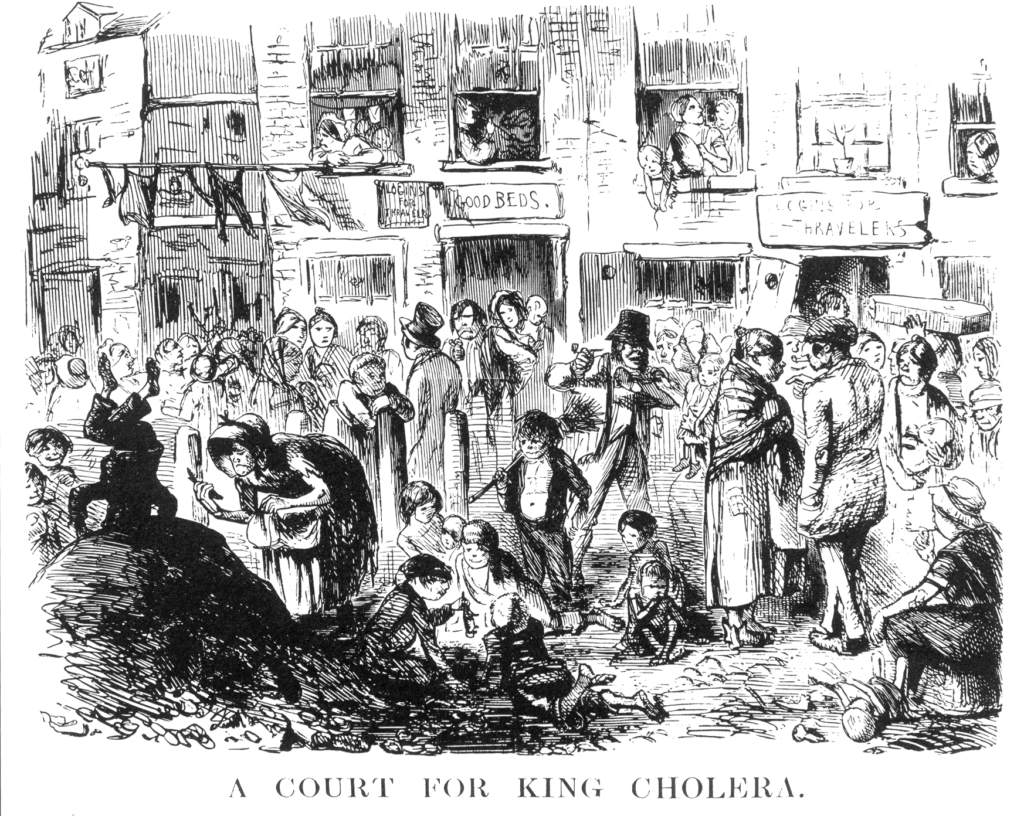

- Cholera was a particularly deadly disease during the Industrial Revolution. With four major outbreaks throughout the mid-19th century and having claimed tens of thousands of lives, it got nicknamed “King Cholera”.

- Cholera epidemics were caused and spread by dirty and contaminated water. This was largely down to the fact that raw sewage was being dumped into the Thames at unprecedentedly high rates.

-

- That same water from the river was also the main drinking source. Therefore, major water pollution combined with a lack of medical knowledge and expertise on cholera made it an impossible disease to tackle all the way up until Dr John Snow in 1854 discovered the true cause of cholera – water.

- Meanwhile, the greatest killer in Britain during the Industrial Revolution was definitely tuberculosis (TB). This disease would attack the entire body, especially the lungs and, although it does not claim as many lives today, back in the 19th century, it very often killed.

- TB can be spread simply by breath and malnourished individuals are particularly susceptible to it. This made Victorian London a ripe scene for the wide spread of TB. Poor living conditions, as many lived in slums, long working hours, and a lack of sufficient food or clean water meant that poor people of all ages could catch TB very easily. It is estimated that in 1800-1850 over a third of all deaths were caused by the illness.

- Moreover, both typhoid and typhus were highly feared diseases during the Industrial Revolution. They too, were caused by poor living conditions and made worse by a lack of medical expertise on their causes and treatments. While typhoid was spread by infected water, typhus was carried on by lice. Both of these were incredibly common in the poorly built and insulated shacks and slums of the East End of London and its factories.

- Poor living conditions

- Rise in industrialisation saw people flock to the cities.

- Poor people lived in crowded and unsanitary conditions and disease spread quickly.

- Town infrastructure could not cope with the demand for clean water and sewage and waste removal.

- Squalid conditions attracted pests and were breeding grounds for pathogens.

- Laissez-faire attitude meant public health was at its worst.

- Poor knowledge of what caused

- Bureaucratic problems

- Some felt the government should force local councils to clean up.

- Laissez-faire attitude meant others felt the government shouldn’t interfere.

- Rate-payers didn’t want to foot the bill for public health improvements through increased taxes.

Public Health Innovations

- Although the first Industrial Revolution had facilitated many widespread public health issues in Victorian London, it also drove many public health improvements. Major discoveries in the causes of infectious diseases and their treatments, coupled with a greater focus on the social impact of the Revolution, provided for the building blocks of publicly funded healthcare.

- Due to the widespread and greatly felt effects of cholera epidemics, many researchers became preoccupied with figuring out the disease’s root cause.

- While for centuries many had been satisfied with the classical miasma theory of disease (one which postulates that noxious air spreads disease), in the 19th century it had become apparent that it was simply insufficient. While there were many well-intentioned efforts to curb cholera epidemics in the 19th century, such as those by the first Health Commissioner of London, Edwin Chadwick, these were simply no good as they relied on the incorrect assumption that the disease was in the air.

Men Of The Hour!

- EDWIN CHADWICK was an English social reformer who reformed the Poor Laws and brought major changes to urban sanitation and public health through scientific surveys. Following a serious outbreak of typhus in 1838, Chadwick convinced the Poor Law Board to investigate. He used doctors to give feedback about whether the conditions of the poor contributed to disease prevalence in their communities.

- JOHN SNOW experienced a number of cholera outbreaks. He established that cholera was waterborne by mapping out cases in Broad Street, Soho, London, which led to a single contaminated well. Further investigation revealed a cracked cesspit nearby was contaminating the water supply. Snow pressurised water companies to clean up their water supplies.

- LOUIS PASTEUR was a French biologist, microbiologist and chemist. He’s renowned for figuring out the principles of vaccination, microbial fermentation and pasteurisation (which is named after him). Through his work, he created the first vaccines for rabies and anthrax. He proved his theory by sterilising water and keeping it in an airtight flask while sterilised water in an open flask grew microorganisms.

Time For Some Experiments!

- Pasteur theorised that if microbes were responsible for souring, then they might be the cause of disease too. He created a series of public experiments to prove his theories.

- He took sterile flasks into the streets of Paris. Once sealed, microorganisms grew in them.

- He repeated the above experiment in different places around France. The number of microorganisms varied by location sampled.

- One flask was filled with sterile air, and no decay occurred. The second flask had normal air and decay occurred.

- He heated material in a flask, removed the air and sealed the flask. The material did not decay.

- Significance of Pasteur’s experiments

- Through Pasteur’s experiments, he made the following important contributions to treating diseases:

- Proved that germs caused matter to decay.

- He proved that spontaneous generation was incorrect.

- Proved that miasma did not cause disease.

- He linked germs to the cause of diseases.

- Robert Koch, a German physician, expanded Pasteur's Germ Theory and is considered to be the founder of modern bacteriology. He identified the causes of TB, cholera and anthrax. His experiments lent support to the concept of infectious disease. His discoveries made a significant contribution to the development of the first ‘magic bullets’.

- Over the course of the next 30 years, debate raged over the need for government and councils to address public health and Poor Law reforms. Chadwick’s recommendations went unaddressed until the passage of the Public Health Act in 1848.

- The Act gave local authorities power to provide a clean water supply, implement drainage and refuse collection and appoint Medical Officers of Health and Sanitary Inspectors.

- As the Act was not compulsory, a Board of Health was set up to encourage councils to participate.

- Funding was given to councils over and above rate-payers to implement improvements.

- By 1872, however, only 50 Medical Officers of Health were appointed, and the Board of Health was abandoned.

Medical discoveries in the 19th century

- Anaesthetic

- Patient comfort during and after surgery drastically improved. More effective anaesthetics meant longer surgeries were possible.

- Germ Theory

- New understanding that bacteria caused decay and diseases meant efforts were directed into finding compounds that killed germs.

- Antiseptic breakthrough

- The introduction of the antiseptic carbolic acid during surgery proved the necessity for sterile instruments and clothing and clean theatres.

- Blood transfusions

- Blood groups discovered in 1900 by Dr Karl Landsteiner, meaning successful transfusions could be given during and after surgery.

Image sources:

[1.] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/8c/Punch-A_Court_for_King_Cholera.png

[2.] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/9e/SirEdwinChadwick.jpg