Download Luddites Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach Luddites to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Table of Contents

Add a header to begin generating the table of contents

Summary

- Emergence of the Luddite movement

- Key events of the Luddite movement

- The fall of the Luddites

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about the Luddites!

- The Luddites were a secret oath-based organisation of English textile workers in the 19th century. They were a radical faction that destroyed textile machinery as a form of protest.

- They railed against the ways that mechanised manufacturers and their unskilled labourers undermined the skilled craftsmen of the day. The economic pressures of the Napoleonic Wars made the cheap competition of early textile factories quite a threat for these artisans, and they began breaking into factories to smash textile machines.

- Luddites are also called frame breakers.

- In 1721, machine breaking became a crime according to the Parliament of the United Kingdom.

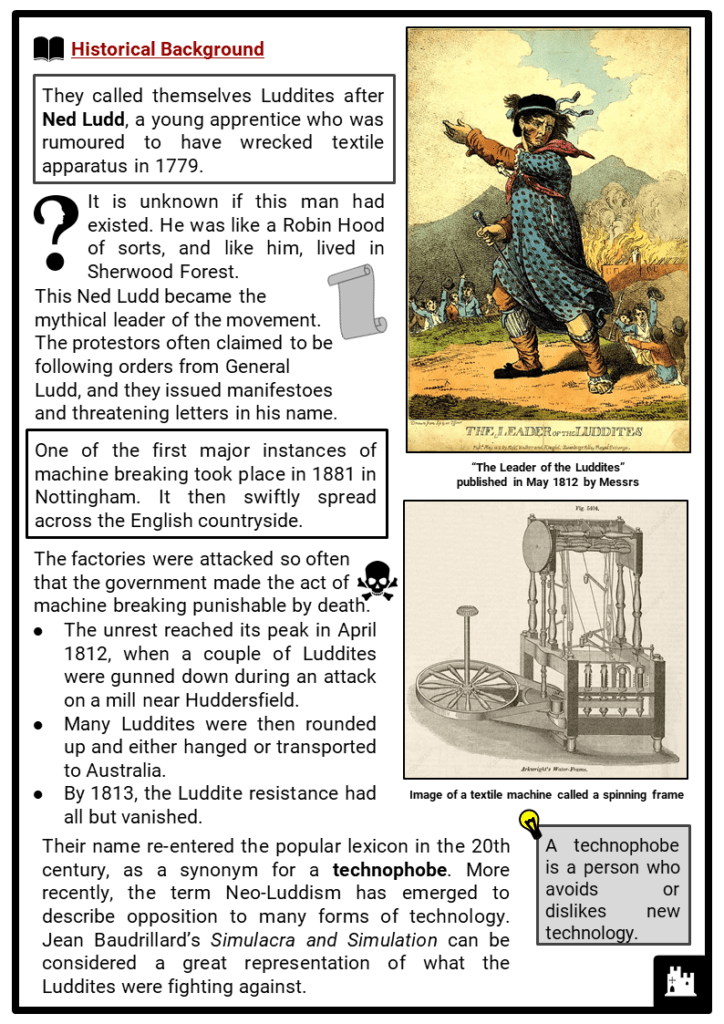

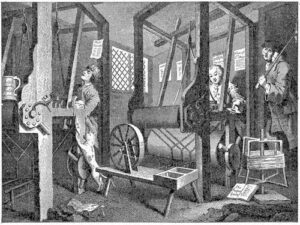

Image of Luddites smashing a loom

Historical Background

- They called themselves Luddites after Ned Ludd, a young apprentice who was rumoured to have wrecked textile apparatus in 1779.

- It is unknown if this man had existed. He was like a Robin Hood of sorts, and like him, lived in Sherwood Forest.

- This Ned Ludd became the mythical leader of the movement. The protestors often claimed to be following orders from General Ludd, and they issued manifestoes and threatening letters in his name.

- One of the first major instances of machine breaking took place in 1881 in Nottingham. It then swiftly spread across the English countryside.

- The factories were attacked so often that the government made the act of machine breaking punishable by death.

- The unrest reached its peak in April 1812, when a couple of Luddites were gunned down during an attack on a mill near Huddersfield.

- Many Luddites were then rounded up and either hanged or transported to Australia.

- By 1813, the Luddite resistance had all but vanished.

- Their name re-entered the popular lexicon in the 20th century, as a synonym for a technophobe. More recently, the term Neo-Luddism has emerged to describe opposition to many forms of technology. Jean Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulation can be considered a great representation of what the Luddites were fighting against.

The Luddite Movement

- The Luddites thought that the time they spent learning the skills of their craft would go to waste as machines would inevitably replace their role in the industry.

- Their movement and ideology became so powerful and symbolic that the term “Luddite”, over time, has come to mean someone opposed to industrialisation, automation, computerisation, or new technologies in general.

- The Luddite movement began in Nottingham, England, and culminated in a region-wide rebellion that lasted from 1811 to 1816.

- The name Luddite is of uncertain origin.

- It is said that the movement was named after Ned Ludd, an apprentice who deliberately smashed two stocking frames in 1779 and whose name had become emblematic of machine destroyers.

- Ned Ludd, however, was probably a fictional character and he was used as a way to shock and provoke the government.

General Ludd

- The name developed into the imaginary General Ludd or King Ludd, who was said to live in Sherwood Forest, just like Robin Hood.

- The protestors claimed to be following orders

from General Ludd, and they also issued manifestoes and threatening letters in his name. - The first major instances of machine breaking occurred in 1811 in Nottingham, and the practice soon spread across the English countryside.

- Machine-breaking Luddites attacked and burned factories, and from time to time exchanged gunfire with company guards and soldiers.

- The Luddites hoped that their raids would deter employers from installing expensive machinery.

- However, the English government moved to quash the uprisings. They passed laws that made machine breaking punishable by death.

Rise of the Luddites

- At the start of the 19th century, British working families were enduring economic upheaval and widespread unemployment.

- A seemingly endless war against Napoleon’s France meant “the hard pinch of poverty hath come into homes where before it had been a stranger” – wrote Yorkshire historian Frank Peel.

- Food was very costly and scarce, and the prices were getting higher and higher still.

- On 11 March 1811, in Nottingham, a textile manufacturing hub, British troops broke up a crowd of protesters demanding more work and better wages.

- This is where Ned Ludd first turned up as part of a Nottingham protest in November 1811. He quickly moved from one industrial centre to the next. This elusive leader inspired the protestors.

- Ned Ludd’s apparent command of unseen armies, drilling by night, also spooked the forces of law and order.

- Government agents made finding him a top priority.

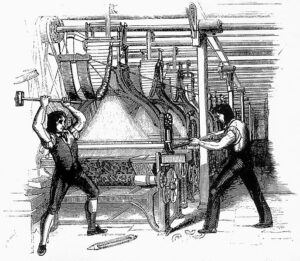

1747 illustration by Hogarth showing hand loom weaving - In one case, a militiaman reported spotting the dreaded Luddite leader with a pike on his hand, like a sergeant's halberd, and he supposedly had a ghostly unnatural white face.

- During that night, workers smashed textile machinery in a nearby village. Similar attacks occurred nightly, at first, then sporadically, and then in waves, eventually spreading across a 70-mile swathe of northern England from Loughborough in the south to Wakefield in the north.

Government Retaliation

- The government feared a national movement and so positioned thousands of soldiers to defend factories.

- Parliament passed a measure to make machine breaking a capital offence. However, the Luddites were neither as organised nor as dangerous as the authorities believed.

- The Luddites indeed set some factories on fire, but mainly they confined themselves to breaking machines. In truth, they inflicted less violence than they encountered.

- For example, in one of the bloodiest incidents, in April 1812, some 2,000 protesters mobbed a mill near Manchester.

- The owner told his men to fire into the crowd, killing at least 3 and wounding 18.

- Soldiers killed at least 5 more the next day. In the same month, a crowd of 150 protesters exchanged gunfire with the defenders of a mill in Yorkshire, and two Luddites died.

- Soon, Luddites there retaliated by killing a mill owner, who in the thick of the protesters had supposedly boasted that he would ride up to his britches in Luddite blood.

- Three Luddites were hanged for this murder, while in other courts, many were sent to the gallows or exile in Australia due to political pressures.

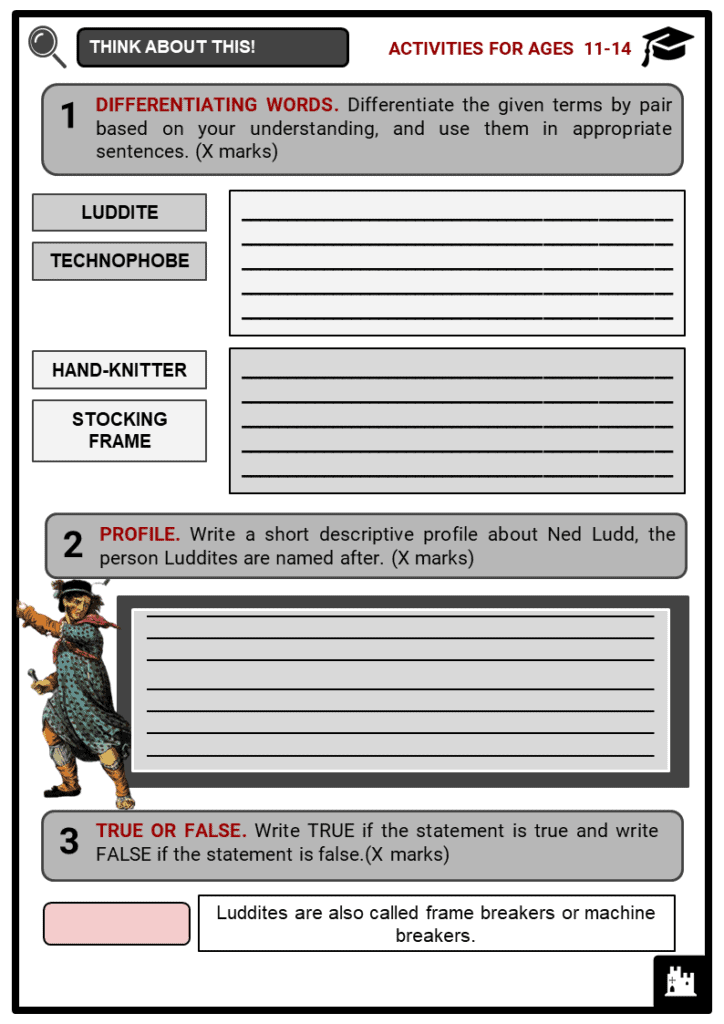

- The Luddites commonly attacked the stocking frame, a knitting machine first developed more than 200 years earlier by an Englishman named William Lee.

- Right from the beginning, concern arose that this invention would displace traditional hand-knitters, and as such, Queen Elizabeth I denied William Lee a patent. Lee’s invention, with some further improvements, helped the textile industry grow and created many new jobs.

- However, labour disputes caused sporadic outbreaks of violent resistance. Episodes of machine breaking occurred in Britain from the 1760s onwards, and in France during the 1789 revolution.

The fall of the Luddites

- The British government sought to suppress the Luddite movement with a mass trial at York in January 1813, following the attack on Cartwright's mill at Rawfolds near Cleckheaton.

- The government charged over 60 men with various crimes in connection with Luddite activities. Most of them had no connection to the Luddite movement.

- Although the proceedings were legitimate jury trials, many were abandoned due to lack of evidence, and around half of the accused were acquitted.

- These trials were intended to act as show trials to deter other Luddites or would-be-Luddites from joining the movement or continuing their activities.

- The harsh sentences of those found guilty which included execution and penal transportation quickly ended the Luddite movement.

- The last major heroic Luddite act is considered to be the Pentrich Rising.

- In 1817, an unemployed Nottingham stockinger named Jeremiah Brandreth led the uprising, but it was not related to

Aftermath

- By 1813, the Luddites had all but vanished.

- It wasn’t until the 20th century that their name re-entered the popular lexicon as a synonym for “technophobe”.

- In 1956, during a British Parliamentary debate, a Labour spokesman said that “organised workers were by no means wedded to a Luddite Philosophy”.

- In our time, the term Neo-Luddism has emerged to describe opposition to many forms of technology.

- According to a manifesto drawn up by the Second Luddite Congress in 1996, Neo-Luddism is a “leaderless movement of passive resistance to consumerism and the increasingly bizarre and frightening technologies of the Computer Age.”

- The term Luddite Fallacy is used by economists to refer to the fear that technological unemployment inevitably generates structural unemployment and is consequently macroeconomically injurious.

- If a technological innovation results in a reduction of necessary labour inputs in a given sector, then the industry-wide cost of production falls, which lowers the competitive price and increases the equilibrium supply point which, theoretically, will require an increase in aggregate labour inputs.