Download Paris Commune Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach Paris Commune to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Events leading to the Paris Commune

- Notable people involved in the Paris Commune

- The impact of the Paris Commune

Key Facts And Information

Let’s learn more about the Paris Commune!

- The Paris Commune was a radical socialist and revolutionary government that ruled Paris from 18 March to 28 May 1871.

- The Commune governed Paris for two months until it was suppressed by the regular French Army during “La semaine sanglante” (“The Bloody Week”) beginning on 21 May 1871.

- The working class, refugees from parts of France occupied by Germany, and immigrants formed the bedrock of the Commune’s popular support.

- The policies and outcome of the Commune had a significant influence on the ideas of Karl Marx, who described it as an example of the “dictatorship of the proletariat”, or the dictatorship of the working class. His works, influenced by the happenings of the Commune, would also later influence Vladimir Lenin.

- The term “dictatorship of the proletariat” was also borrowed by Marx from Louis Auguste Blanqui, the honorary president of the Commune.

- All the revolutions in France, like the ones in 1789, 1830, and 1848, did little for the common working man and woman and more for the middle class than anything else. This paved the way for the Paris Commune.

- It was one of the first, modern, left-wing revolutions in the world, and it sought to implement some of the most radical ideas of the French Revolution of 1789. The revolutionaries were influenced by anarchism and were in many ways the precursors of Soviet Communism in Russia in the early 20th century.

- Even if the Commune was defeated, it served as a model to many revolutionaries at that time and still to the present day.

Prologue

- After France’s defeat at the Battle of Sedan in the Franco-Prussian War on 2 September 1870, Emperor Napoleon III surrendered to the Prussian Chancellor, Otto von Bismarck. News of this reached Paris the next day, and shocked, angry crowds came out into the streets. The wife of Napoleon and acting Regent at the time fled the city. The government of the Second Empire swiftly collapsed. Republican and radical deputies of the National Assembly went to the city hall – Hotel de Ville – and proclaimed the new French Republic.

- The Government of National Defense was also formed. Though Napoleon III and the French army had been defeated at Sedan and taken as prisoners, the war continued. The German army marched swiftly towards Paris. The Government of the Second Empire swiftly collapsed. Republican and radical deputies of the National Assembly went to the Hotel de Ville, proclaimed the new French Republic, and formed a Government of National Defense. Thus, the war continued.

- At this time, France was divided between rural conservative countryside Frenchmen and the more Republican and radical people living in the cities.

- The following numbers of the 1869 parliamentary elections held under the French Empire show us the political standing of the people:

- 4,438,000 people voted for the Bonapartist candidates supporting Napoleon III.

- 3,350,000 people voted for the Republican opposition.

- The difference was over a million people. Yet, in Paris, Republican candidates dominated, winning with 234,000 votes, while the Bonapartists had just 77,000 votes.

- In Paris, out of 2 million people, 500,000 of them were industrial workers, with another 300,000 or more workers in other enterprises. Alongside the Parisians, there were about 100,000 immigrant workers and political refugees mostly from Italy and Poland. Due to the war, these people suffered the most from a lack of industrial activity and thus formed the bedrock of the Commune’s popular support since its inception.

The beginning of the Commune

- Growing discontent among Parisian workers resulted in the creation of the Commune. The discontent can be traced all the way to the first worker uprisings in 1830, named the Canut revolts. In fact, all of the revolts that happened in France until now were just a temporary relief to the common man. It offered very little in return. Big changes were not happening at all, or it was at a very slow and frustrating pace.

- The majority of the Parisian people supported a democratic republic. They wanted Paris to be self-governing with its own elected council, something enjoyed by the smaller French towns but denied to Paris by a national government wary of the capital’s unruly population. Cries for a more “just” way of managing the economy were often heard among the people, not necessarily socialist but something summed up in the popular appeal for “the democratic and social republic!”

- Socialist movements, such as the First International, had been growing in influence, with hundreds of affiliated societies all across France. The Internationalists elected a new committee and put forth a more radical program, but authorities imprisoned their leader. Therefore, a more revolutionary perspective was taken to the International’s 1868 Brussels Congress. This movement had considerable influence even among unaffiliated French workers, particularly in Paris and the big towns. One specific event upset them more than any other event to date. The killing of journalist Victor Noir and the arrests of journalists critical of the Emperor enraged the Parisians. The tensions eased significantly in 1870 after the plebiscite in May. The war with Prussia, initiated by Napoleon III in July, was initially met with patriotic fervor.

- Of the radical and revolutionary groups in Paris at the time of the Commune, the most conservative were the “radical republicans”. This group included the future Prime Minister, Georges Clemenceau, who was a member of the National Assembly. He tried to negotiate a compromise between the Commune and the government but failed because both sides distrusted him. He was considered extremely radical by the provincial deputies of rural France, yet he was too moderate for the leaders of the Commune. The most extreme revolutionaries in Paris were the followers of Louis Auguste Blanqui, a charismatic professional revolutionary who spent most of his adult life in prison.

- The Blanquists were mostly armed and organised into cells of ten people each. Each cell operated independently unaware of other members from other groups. They communicated with their leaders through codes. Though their numbers were small, the Blanquists consisted of the most disciplined soldiers and several of the senior members of the Commune. Blanqui had written a manual on revolution, “Instructions for an Armed Uprising”, to give guidance to his followers.

- By 20 September 1870, the German army had reached and surrounded Paris but maintained a distance. The regular French army soldiers under General Trochu were few in number, with the majority of them being prisoners of war or trapped in the city of Metz, surrounded by Germans. They had some support from the Garde Mobile, which was a unit comprised of new recruits with little experience or training.

- The largest armed force stationed in Paris was the National Guard, but they also lacked training and experience. They were organised by neighbourhoods and were divided between them. Those from the upper and middle class tended to support the national government, while those from the working-class neighbourhoods were far more radical and politicised.

- They were known for their lack of discipline. Some refused to wear uniforms, refused to obey orders without discussing them, and demanded the right to elect their own officers. They later became the main armed force of the Commune.

Siege of Paris

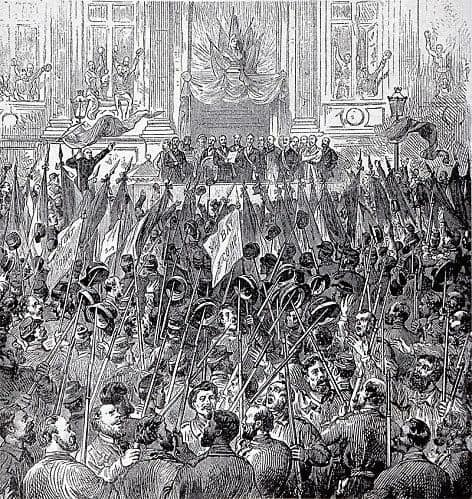

- As the Germans surrounded Paris, radical groups saw that the Government of National Defense had few soldiers to defend itself. Thus, they began demonstrations against it. On 19 September, National Guard units from various neighbourhoods marched to the centre of the city and demanded that a new government, a Commune, be elected.

- Regular army units engaged them, and they eventually dispersed peacefully. On 5 October, five thousand protesters marched from Belleville to the Hotel de Ville, demanding immediate municipal elections and rifles. They were ignored. Three days later, more soldiers from the National Guard, led this time by Eugene Varlin of the First International, marched to the centre and started chanting “Long Live the Commune!”, but they also dispersed without incident.

- Later in October, General Louis Jules Trochu launched a series of armed attacks to break the German siege. However, his men suffered heavy losses and achieved nothing. The Germans proceeded to cut the telegraph line connecting Paris with the rest of the country. Due to this, Defense Minister Leon Gambetta departed the city by balloon in order to try and organise national resistance against the Germans. On 28 October, news arrived in Paris that the French troops in Metz had surrendered. On the same day, another attempt by the French army to lift the siege failed. This motivated the leaders of the main revolutionary groups in Paris, including Blanqui, Felix Pyat, and Louis Delescluze, to organise new demonstrations on 31 October.

- Protesters against General Trochu gathered in front of the Hotel de Ville, calling for his resignation and demanding the proclamation of a commune. Shots were fired from the Hotel de Ville, and the protestors crowded into the building, further demanding the creation of a new government. Yet again, they were pushed back by reinforcements coming to the aid of General Trochu. In the meantime, Adolphe Thiers, the leader of the National Assembly conservatives, had traveled to and tried to form an alliance with different European states to fight against the Germans.

- However, none of those states were willing to support France. With no other alternatives, he met with Bismarck on 1 November for negotiations. Bismarck demanded the cession of all of Alsace, parts of Lorraine, and enormous reparations. The Government of National Defense decided to continue the war, though. They raised a new army but only managed to win one battle. The Parisians were starving, and resources were cut short by the Germans. By early January 1871, tired of the prolonged siege, Bismarck decided to start bombarding Paris.

- On 26 January, the leaders of the Government of National Defense in Bordeaux had finally concluded that the war could not continue. They signed a ceasefire and armistice, with special conditions for Paris. The Prussian Army, under the terms of the armistice, held a brief victory parade in Paris on 17 February. Bismarck honored the armistice and provided trainloads of food to Paris and withdrew the Prussian forces to the east of the city. There was a full withdrawal once France agreed to pay five billion francs for war indemnity.

The Paris Commune

- Prior to the armistice, under the pressure of siege and hunger, factions of the left-wing resistance to the government became desperate. This led to firefights with the government forces. As France negotiated a ceasefire with Germany, the National Guard seized 400 old bronze cannons. They took the cannons into the working-class neighbourhoods in Paris. They were ready to arm themselves against the French government.

- The government tried to negotiate to get some of them back, yet they were also unwilling to prolong a freeze on debt collection and shuttered radical newspapers. These government actions only managed to further aggravate the situation with the Parisian radicals. They were now even less willing to come to the negotiation table. The cannons were stored up on a hill named Montmartre to keep them away from the Prussians and the French government. Thiers ordered an army to seize the cannons. They were led by General Claude Lecomte. A woman by the name of Louise Michel, together with a crowd of other women, stopped the soldiers by shouting at them, “How dare you to disarm the working class?”

- Lecomte ordered his soldiers to shoot down the women, but the soldiers refused and instead arrested Lecomte. At this point, the ruling class panicked, and what was left of it in Paris ran away to Versailles. Paris was left literally without any government of the bourgeoisie. Only the federation was left, which was the armed soldiers and the armed working class.

- They began to run Paris for themselves. In a sense, this was the origin of the Commune and their greatest victory up to this point. On 28 March, the Paris Commune held its first meeting.

- The Commune adopted the Socialist red flag rather than the Republican tricolor and made Louis Blanqui their honorary president, but they had no official president, mayor, or anything else. Everything was established through commissions for different aspects of governing the city. Two main currents held the power in all the debates, the Blanquists and the Proudhonists. The Blanquists took action and decided for everybody else, and Blanqui essentially invented the concept of the dictatorship of the proletariat that Marx later borrowed.

- Blanqui was very keen on the issue of power. He wanted to march to Versailles to destroy what remained of the government. He believed that only then could a new society be established.

- The Proudhonists were anarchists who considered all authority as being bad. Therefore, they didn’t wish to march on Versailles to overthrow what remained of the government. They were not interested in defeating or establishing authority in Paris. As a decision could not be made, they chose to hold a municipal election. Before long, separation of church and state, the abolition of rent and debt interest, and worker self-management were all part of the law.

- Women played a massive role in the commune, highly elevating their status during the time, even though they weren’t allowed to vote. In a sense, they started the whole revolution.

- Louise Michel carried out both combat and maintenance of the commune. She was nicknamed the “French Grande Dame of Anarchy”. Louis helped the injured and even grabbed a gun and uniform for herself. She was not alone, though. Many women recognised the liberation and fought alongside the National Guard.

- The commune abolished the death penalty and conscriptions. Education and women’s rights were greatly advanced. Women gained divorce rights, higher education, and more participation in the workforce. The Paris Commune readjusted the estates of the rich to house the poor and took the power of the church. A new education system was proposed that would allow any person to benefit from the same education regardless of ethnicity, gender, or background, combining both theory and manual work. They readjusted the factories, both abandoned and new, to be run democratically and transformed the churches into locations where they could further discuss ideas.

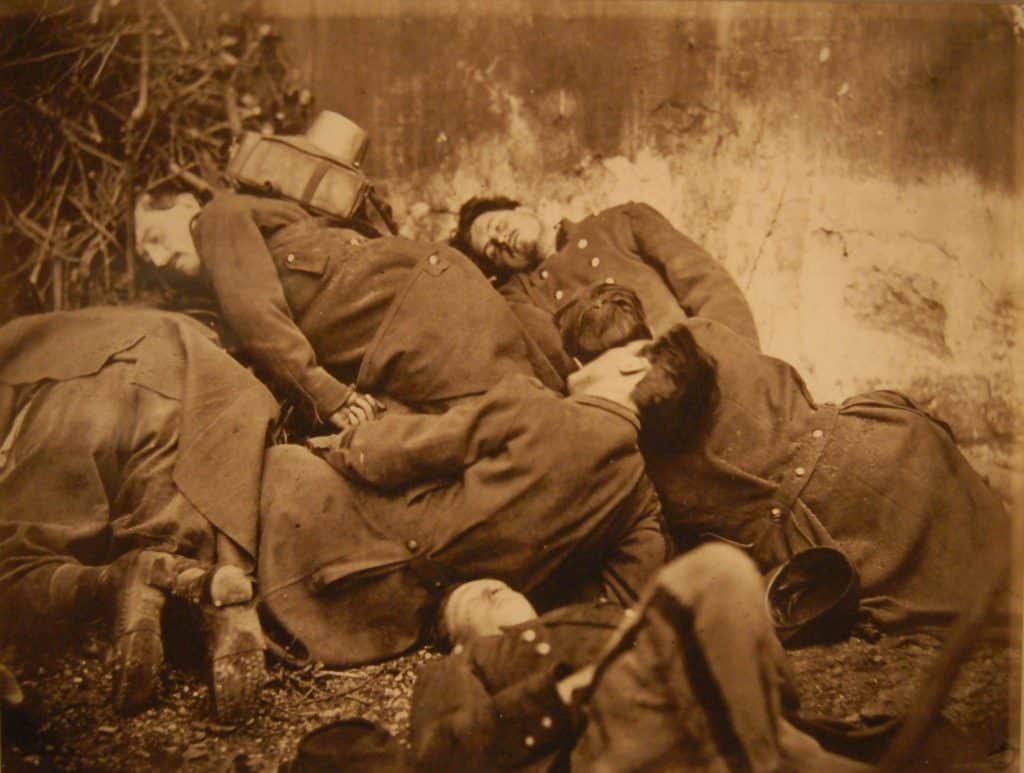

The Bloody Week

- All of this eventually came to a brief end. Some Blanquists tried an offensive takeover of Versailles, but it was a quick failure and the French army put them on the defensive. The Communards’ military was disorganised, and few took their role seriously, abandoning their posts without leave. Even fewer knew how to use the cannons that they acquired.

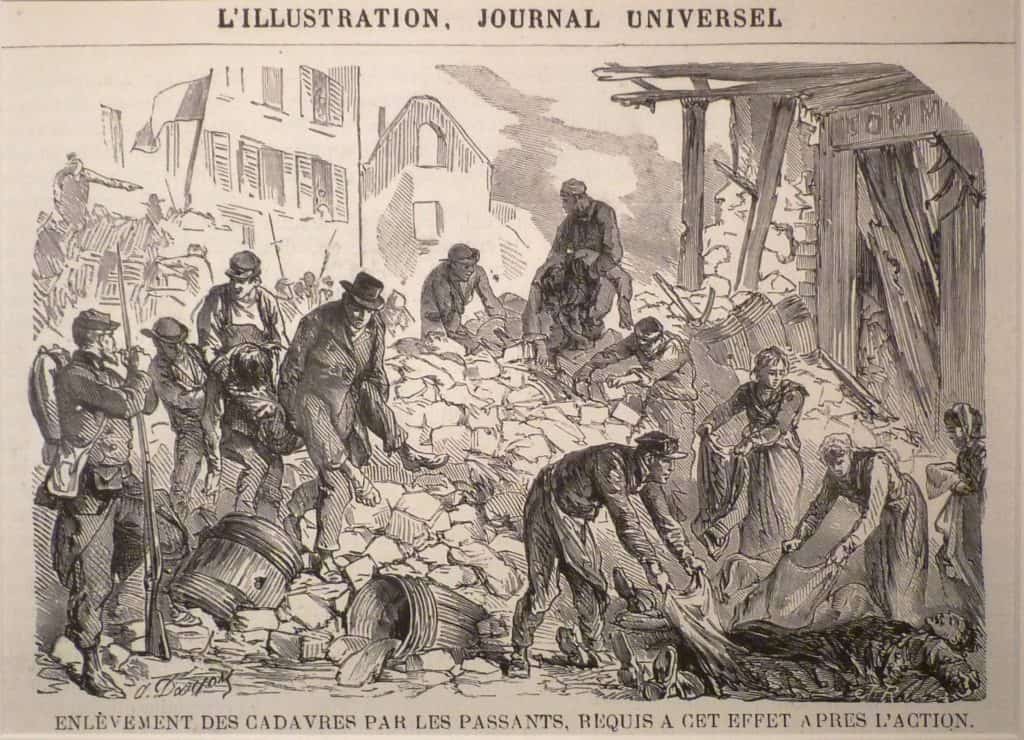

- The French army began its offensive on 21 May. They found an area of the city unfortified, and French troops marched into Paris. The disorganised military of the Commune began to dissolve as the battle moved from street to street. Soldiers broke ranks to save their neighbourhoods. The takeover of the city is often called The Bloody Week. The government wanted to suppress the revolt, as well as make sure no one would ever think to do this again.

- There were mass executions with mass graves that are still uncovered to this day. The government took the few survivors and exiled them around the world.

Aftermath

- Several prominent left-wing thinkers were alive to witness what happened at the Commune. This includes Karl Marx. For left-wing activists, thinkers, and revolutionaries, the Paris Commune was a unifying story. For a short amount of time, a revolutionary experiment in democracy took place. The Commune was the model for how to run a democracy, and overthrow the oppressors. It held a lot of success that many anarchists and communists refer to. The Soviet Union sang the commune’s anthem.

- Lenin himself celebrated when the Soviet Union had lasted longer than the Paris Commune. The Paris Commune is very important because it demonstrated that ordinary people can run society. Soon after the Paris Commune took power in Paris, revolutionary and socialist groups in several other French cities tried to establish their own communes.

- None of the other skirmishes lasted more than a few days, and most ended with little or no bloodshed. Adolphe Thiers was formally elected the first President of the French Third Republic, the leader of the army that crushed the Commune. Patrice MacMahon replaced Thiers as president later on. Clemenceau restored the regions of Alsace and Lorraine to France after World War I. Most leaders of the Paris Commune lived long afterward, and some of them resumed their political careers in France.

Image sources:

[1.] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/2e/Barricade_Voltaire_Lenoir_Commune_Paris_1871.jpg

[2.] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/23/Louis_Auguste_Blanqui.JPG

[3.] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/c4/Commune_28_mars.jpeg

[4.] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/8f/Le_31_octobre_1870.jpg

[5.] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/5/50/Adolphe_Thiers_Nadar_2.JPG

[6.] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/c3/Communecannon.jpg

[7.] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/06/Louise_Michel2.jpg

[8.] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/4d/Communepawnshop.jpg

[9.] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/93/Combats_dans_la_rue_Rivoli.jpg

[10.] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/1c/Cadavres_Soldats_Federes_Commune_Paris_1871.jpg

[11.] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/5/57/Commune_de_Paris_enl%C3%A8vement_des_cadavres_par_les_parisiens.jpg