Download Battle of Hastings Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach Battle of Hastings to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Table of Contents

Add a header to begin generating the table of contents

Summary

- England’s Crisis of Succession

- King Harold’s and Duke William’s preparations before the war

- The day of the battle, and its aftermath

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about the Battle of Hastings

- The Battle of Hastings happened in the early hours of the morning on the 14th of October, 1066 between the Norman-French army of William the Conqueror and the English army of King Harold II. It is acknowledged to be one of the most famous and important battles to have brought a significant cultural transformation throughout English history. The exact number of troops involved in the battle remains unknown. Studies suggest that around 7,000 soldiers helped King Harold to resist the 10,000-strong army of William the Conqueror.

Introduction to the Battle of Hastings

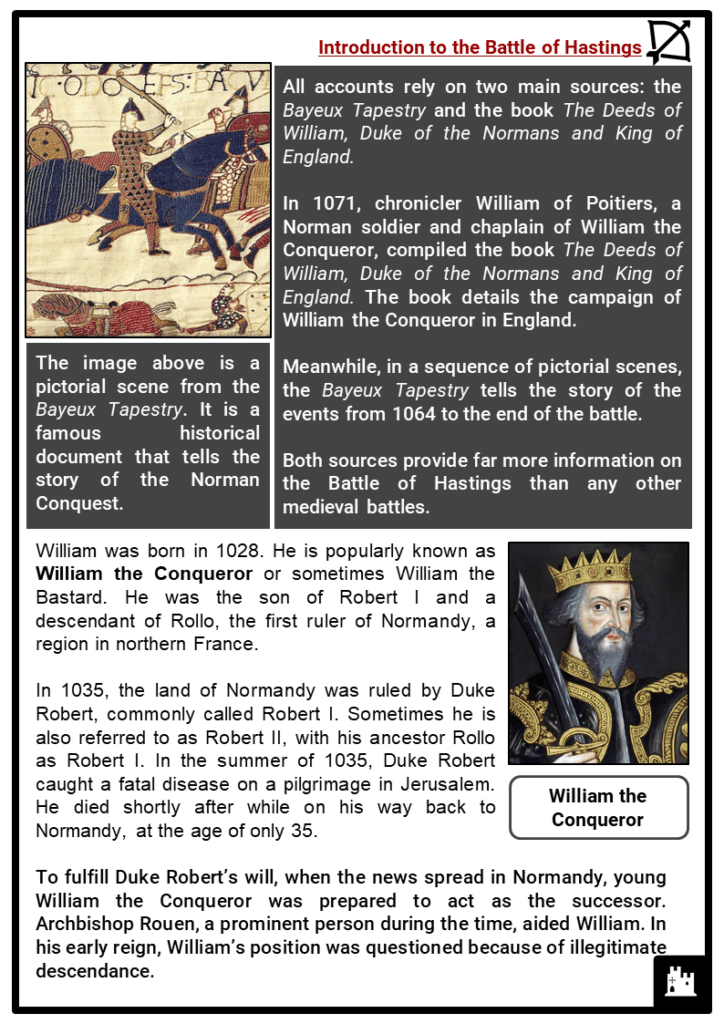

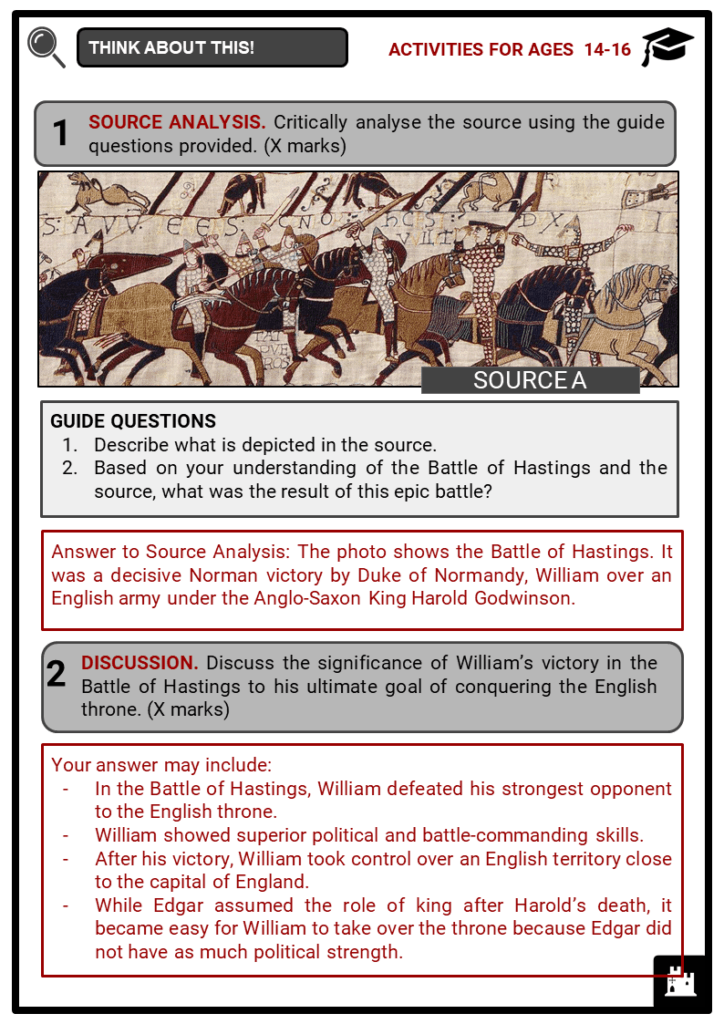

- All accounts rely on two main sources: the Bayeux Tapestry and the book The Deeds of William, Duke of the Normans and King of England.

- In 1071, chronicler William of Poitiers, a Norman soldier and chaplain of William the Conqueror, compiled the book The Deeds of William, Duke of the Normans and King of England. The book details the campaign of William the Conqueror in England.

- Meanwhile, in a sequence of pictorial scenes, the Bayeux Tapestry tells the story of the events from 1064 to the end of the battle.

- Both sources provide far more information on the Battle of Hastings than any other medieval battles.

- William was born in 1028. He is popularly known as William the Conqueror or sometimes William the Bastard. He was the son of Robert I and a descendant of Rollo, the first ruler of Normandy, a region in northern France.

- In 1035, the land of Normandy was ruled by Duke Robert, commonly called Robert I. Sometimes he is also referred to as Robert II, with his ancestor Rollo as Robert I. In the summer of 1035, Duke Robert caught a fatal disease on a pilgrimage in Jerusalem. He died shortly after while on his way back to Normandy, at the age of only 35.

- To fulfill Duke Robert’s will, when the news spread in Normandy, young William the Conqueror was prepared to act as the successor. Archbishop Rouen, a prominent person during the time, aided William. In his early reign, William’s position was questioned because of illegitimate descendance.

- When William reached the right age and independently ruled as Duke of Normandy, the early years were a constant struggle for power. He used this time to hone his political and battle-commanding skills.

The Godwinsons

- King Edward was involved in an internal quarrel with the powerful House of Godwin. He used the absence of an heir as a tool in his political game and encouraged William’s ambitions for the English throne.

- Godwin, also spelled Godwine, became Earl of Wessex in 1018. As one of the most powerful men in England, he helped secure the English throne for King Edward. In 1045, Godwin became more powerful when his daughter, Edith, and King Edward got married.

- In 1051, when Godwin and his sons prevented the rise of Norman influence in the Anglo-Saxon royal court, they were banished by King Edward who then chose William as his heir.

- By 1052, Godwin and his sons emerged from exile and got back to England. He reclaimed his position as Earl of Wessex and accepted the king’s choice of successor.

- Godwin died on the 15th of April 1053. Harold, the oldest living son, succeeded his father as Earl of Wessex and became the king's trusted advisor. He was arguably one of the most powerful figures in England after the king.

- At the end of 1065, King Edward fell into a coma. According to Vita Ædwardi Regis, a historical manuscript, King Edward died on the 5th of January 1066. Some claim that the old king regained consciousness shortly before his death, commended his widow and entrusted the kingdom to Harold. Harold’s coronation took place in Westminster Abbey. This happened just one day after King Edward’s death.

England’s Crisis of Succession

- Meanwhile to the south, William pursued the expansion of his rule. By the year 1066, he reigned over the entire northern French coast from Brittany to Flanders. He received the Church’s blessing and nobles flocked to his cause.

- Upon hearing of King Edward’s death, William immediately set out to claim his right to the English throne, but he was not the only one interested.

- Harald Hardrada Sigurdsson, or Hardrada of Norway, was crowned as King of Norway from 1046 to 1066. He was one of the claimants for the English throne. Hardrada based his claim on an agreement made 30 years earlier between Harthacnut, King of England, and Magnus, King of Norway.

- In early September of 1066, Hardrada invaded northern England. He led a fleet of more than 300 ships with perhaps 15,000 men aboard. Hardrada’s army was further augmented by the forces of Tostig, who supported the Norwegian king's bid for the English throne. Advancing on York, Hardrada’s forces occupied the city after defeating the northern English army on the 20th of September 1066 at the Battle of Fulford. He will then cross paths with Harold in the Battle of Stamford Bridge.

War Preparations

- Harold’s preparations with the English army

- The fyrd was composed of men who owned their own land and were equipped by their community to fulfil the king's demands for military forces. This was a type of early Anglo-Saxon army that was mobilised from freemen to defend their shire.

- England could provide about 14,000 strong men. Harold’s army also consisted of household bodyguards called Housecarl. The English army, however, did not have a notable count of archers.

- In mid-1066, Harold produced a large army and fleet in the south coast of England, waiting for William to invade. During the same time, Hardrada seized Northern England with 10,000 soldiers. Learning of the Norwegian invasion, Harold rushed north, gathering forces along the way. Hardrada was eventually defeated and killed in a surprise attack by Harold’s forces in the Battle of Stamford Bridge on 25th of September 1066.

- The English victory came at great cost, as Harold's army was left in a battered and weakened state.

- William’s preparations and arrival in England

- Just after winter in January 1066, William ordered shipwrights to build a war fleet capable of transporting a large army to England. While thousands of trees were being cut down, William gathered all the nobles willing to back his cause. France, Brittany and Flanders were attracted and offered help to William who promised wealth and positions in return.

- All of William’s preparations were completed by early August, gathering a total number of 7,000 men.

Forces of Norman

- Because of unfavourable north winds, William did not rush to invade England. It was also possible that he knew Harold expected the Norman invasion with his army camping near the Isle of Wight. Harold was forced to disassemble his troops by September due to depleting supplies and harvest time being just around the corner.

- The wind finally changed course and William departed the Norman coast on the 27th of September 1066.

- Norman forces at Hastings

- On the 28th of September 1066, William’s fleet reached the English shores. An anecdote says that upon landing, William slipped and fell on the ground, scaring superstitious folk. But he kept his composure, grasped a handful of soil and proclaimed: “Engletere is ours!”.

- The Norman forces took their time, marched east to set up a temporary camp near Hastings and fortified the town. From there, William mustered his troops and launched parties to plunder the region.

- Companions of William the Conqueror

- Robert de Beaumont

- Eustace, Count of Boulogne

- William, Count of Evreux

- Geoffrey, Count of Mortagne & Lord of Nogent

- William fitz Osbern

- Aimeri, Viscount of Thouars

- Walter Giffard, Lord of Longueville

- Hugh de Montfort, Lord of Montfort-sur-Risle

- Ralph de Tosny, Lord of Conches

- Hugh de Grandmesnil

- William de Warenne

King Harold’s Preparations

- King Harold moves south

- Meanwhile, after an exhausting, four-day march, Harold feasted in York to celebrate their bloody victory over the Norwegian forces.

- He promptly ceased the celebrations after learning that Normans had landed to the south. Together with his best men, Harold rushed back to London. He reached the capital in one week and spent an additional week to prepare for the upcoming encounter. Harold kept all of the Housecarls who survived the bloodbath of Stamford Bridge, and gathered new fyrd units too.

- Harold’s army was roughly similar in size to the Norman troops. He could have probably waited a few more days to allow more soldiers to join. However, Harold's confidence after the last battle and eagerness to relieve the people harmed by the Normans pushed him to set off as soon as his forces were ready.

- Harold hoped to use the element of surprise like he did against the Norwegian army two weeks earlier.

- Up to now, it is unclear what the exact number of Harold’s troops was. Recent historians suggest that the number of soldiers ranged between 5,000 and 13,000. Other modern historians argue for a figure of 7,000–8,000 English troops.

The Battle

- Background and Location

- The battle took place seven miles (11 km) north of Hastings at the present-day town of Battle, between two hills – Caldbec Hill to the north, and Telham Hill to the south. The area was heavily wooded, with a marsh nearby. The name traditionally given to the battle is unusual – there were several settlements much closer to the battlefield than Hastings.

- Forces and Tactics

- On the day prior to the battle, William's scouts found out that the English army had departed London and was marching south.

- Upon learning that William had set out for Hastings, Harold started to seek out a suitable place to deploy his units. He finally decided to hold a defensive position on top of the hill just over six miles (10 km) northwest of the town in between forested and marshy terrain.

- The composition of Harold's army did not change much since Stamford Bridge. He relied solely on infantry comprised of professional Housecarl units and a poorly armed and untrained fyrd formation levied days prior to the battle.

- In contrast, William commanded a mix of infantry, archers and cavalry. His army deployed into three divisions, roughly corresponding to the origin of the troops. The front line was formed by archers, who had their back secured by infantry units. The mounted force or horsemen was held in reserve as a third line.

- While holding a good defensive position on higher ground, with his flanks covered by marshes and woods on both sides, Harold could barely do anything more than just defend. His Housecarl ranks were thinned out after the last battle and were unable to play a more active role.

- The majority of fyrd units, though fierce and determined to fight for their land, were mostly poorly armed and unskilled peasants that posed limited threat to the enemy.

- Beginning of the Battle

- Norman archers started the battle by attempting to weaken the tightly packed English lines. The archers were shooting uphill at an unfavourable angle, with little effect. Arrows either bounced off the shieldwall or landed far behind the English positions.

- Then, William sent the infantry units to engage in melee fighting, hoping to break Harold's shieldwall. The advancing Normans suffered a barrage of axes, stones and spears, but eventually reached English front ranks and hand-to-hand combat began.

- Casualties rose on both sides. Norman infantry failed to punch a hole in the Saxon line, so William sent idling cavalrymen hoping to crush Harold's solid defence.

- Battle raged for hours. Due to heavy losses, many fyrd units were forced to replace the fallen Housecarls in the first line. The Normans lost many men as well. Even William had his horse slain under him, which caused a rumour that he was dead.

- Around midday, William's left plank comprised of Bretons retreated and many of the other units followed. It is not clear whether it was a real flight or just a feigned retreat planned and performed by William.

- Death of Harold

- Many of the battle-frenzied Anglo-Saxon militia pursued the running enemy, disobeying Harold's order to remain in formation and thus crippling their only chance for victory. The Normans stopped the retreat and attacked drawn-off English units which were soon surrounded and crushed by Norman cavalry. Harold's remaining troops fought bravely for the rest of the day, struggling to withstand William's now dominant forces at the cost of very heavy losses.

- When the sun was about to set over the horizon, Harold's brothers Gyrth and Leofwine were slain. Harold was struck in the eye by an arrow. This triggered a final massive rout of the then leaderless Saxon forces.

- William won the battle. He ascended to the English throne 2 months later. The Battle of Hastings marked the beginning of the Norman Conquest which took several years and heavily influenced both English and European history.

Aftermath

- William won the battle and defeated Harold. He was victorious at the Battle of Hastings, but he was yet to conquer the English throne. How then did he become 'the conqueror’? The victory at Hastings on the 14th of October 1066 did not make him King of England – at least, not immediately.

- After his victory at the Battle of Hastings, William marched to London together with his Norman army. For another two months, they were not allowed to enter the city. William devised a thorough plan to penetrate the English capital.

- Upon learning that the London Bridge was heavily guarded, William opted against a full-blown assault on the capital. He instead embarked on a destructive march through nearby Surrey and Hampshire. Burning and pillaging towns as they went, his troops captured the royal treasure at Winchester. In the middle of November, William’s troops had crossed the Thames and were based at Wallingford.

- Due to an empty throne, a new king was proposed. Within England's ranks, the young Edgar Atheling, a grandson of the earlier ruler, King Edmund II, was eyed as successor. Edgar was proclaimed the king, but without the leadership of Harold Godwinson’s powerful family, the English resistance rapidly began to crumble. Prominent nobles and powerful clergymen deserted Edgar, fleeing the capital. Come mid-December, the remaining English leaders in London submitted to William at Berkhamsted.

- On Christmas Day of 1066, William the Conqueror was crowned the first Norman king of England in Westminster Abbey. The Anglo-Saxon phase of English history came to an end.

- Upon the death of William the Conqueror in 1087, his son, William Rufus became William II, the second Norman king of England.