Holy Roman Empire Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the Holy Roman Empire to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Origin of the Empire

- Charlemagne and His Successors

- The Investiture Controversy

- The Empire in Modern Times

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about the Holy Roman Empire!

The Holy Roman Empire refers to the territory in western and central Europe first ruled by Frankish and then German kings. It is also known as the German Heiliges Römisches Reich and the Latin Sacrum Romanum Imperium.

Since 1034, the lands ruled by Conrad II have been referred to as the Roman Empire. The term Holy Empire was already in use in 1157, but from 1254 on, Sacrum Romanum Imperium was considered a more precise term.

Origin of the Empire

- The Western Roman Empire fell in 476, so there was no rational reason for the establishment of Germanic kingdoms there. Nonetheless, the concept of a universal and eternal Roman Empire persisted. The newly established Germanic kingdoms’ kings, such as Clovis in Gaul and Theodoric the Great in Italy, gladly accepted Roman titles. The Byzantine emperor, who bestowed Roman titles on the Germanic kings, intended to treat them as his vicars and lieutenants to maintain the Roman Empire’s formal unity, but this did not last long.

- There was a reconciliation between Christianity and the Roman Empire after Constantine the Great converted to Christianity. Because of the good relations, the barbarians of the West were drawn to the concept of the Christian Empire.

- The Christian church evolved into a state church, with the empire and its emperors included in liturgical prayers.

- The establishment of the Christian Roman Empire became a requirement for the establishment of a Western empire. Over time, the precondition gave way to political facts, resulting in established politics in the empire.

- In the Byzantine Empire, the emperor confirmed the pope’s bishopric. However, by the eighth century, the imperial position in Italy was being challenged by the power of Islam, which the Lombards used to conquer a portion of Italian lands.

- The popes remained loyal to the Byzantine emperor. But that loyalty was also tested when the Lombards resumed their southward advance and took Ravenna in 751.

- The Byzantine emperor then asked for help from Frankish king Pippin III the Short. The Frankish king invaded Italy in 754, defeating the Lombard king Aistulf. Pippin granted the papacy temporal power and a close alliance with the Frankish monarchy in 756.

- The papacy was regarded as an anomalous position. The pope had the privilege of discussing issues and decisions with the Frankish king, which previously only the emperor had.

- Given the Byzantine emperor and the Frankish king, the pope’s position was difficult. The pope hoped that when the exarch was expelled in 751, he would become the emperor’s successor in the West.

Charlemagne

- When Pope Leo III was attacked in Rome in 799, he went to his protector, Charlemagne. However, as suggested by Alcuin, Charlemagne sent the pope back to Rome with a commission. The pope was arrested, but he quickly dropped the false charges against him. On 25 December 799, the pope was about to formally crown Charlemagne’s son king when Leo placed the crown on his head. The assembled Romans recognised the newly crowned king as Augustus and emperor.

Reliquary bust of Charlemagne - The coronation of Charlemagne enraged the Frankish king because it was the work of the papacy, not his. While his title was legally invalid, Charlemagne needed Constantinople’s recognition.

- Because the pope had no right to make Charlemagne emperor, the Byzantines saw the coronation as forced. As a result, Charlemagne’s territories were restricted to the duchy of Rome and the former exarchate.

- In 797, Constantinople empress Irene blinded and deposed her son Constantine VI, allowing her to take his place and become the empire’s first female ruler. However, Alcuin in the West saw her dubious constitutional position as empty.

- According to one of Theophanes’ chronicles, Charlemagne proposed marriage to Empress Irene in the hope of reuniting the East and West. However, the plan was abandoned when the empress was deposed in 802.

- In 812, the Byzantine emperor Michael I recognised Charlemagne’s imperial title after the two had just negotiated over a widely expected war. The emperor of Constantinople, on the other hand, was certain that he was the only true successor to the Roman Caesars, considering that what Charlemagne was granted was only a personal title. Charlemagne and his territory developed a rivalry with Constantinople.

Successors of Charlemagne

- In 813, Michael I agreed to share imperial power with Charlemagne’s surviving son, Louis. The ceremony was held in Aachen’s imperial chapel without the presence of the pope.

Louis I, the Pious

The Carolingian Empire

- Louis I the Pious had a very different mindset than his father because he saw the word ‘empire’ as an idea that needed to unite various dominions, so he gave up his other royal titles, which was Louis’ claim in the Ordinatio Imperii.

- As a result, Louis elevated his eldest son, Lothar I, to the throne. Pippin and Louis the German, his younger sons, received the kingdoms of Aquitaine and Bavaria.

- The Frankish lands engaged in civil war against Louis I’s ideas, which aided the papacy by increasing its influence by supporting one of the debating parties.

- In 816, Pope Stephen IV convinced Louis to be anointed and recrowned by him, to repair the unofficial crowning in 813.

- Paschal I recrowned Lothar I in Rome in 823 to strengthen his title after his father made him an emperor six years before.

- Louis II was crowned by the pope in 850 and succeeded Lothar as emperor after his death in 855.

- In 875, he was succeeded by his uncle Charles II the Bald, who reigned for only two years.

- In 881, Charles III the Fat was elevated to the throne, but his empire quickly declined due to the deposition of wealthy East Frankish citizens.

- Since 888, France, Germany and Italy have been independent states, while the ownership of the kingdoms of Burgundy and Lotharingia has been contested. As a first step, a succession of emperors from among Italy’s nobles was chosen.

- Guy of Spoleto became emperor in 891 and was succeeded by his son Lambert three years later.

- Overlapping with Lambert’s reign, which ended in 898, East Frankish king Arnulf was crowned emperor in 896 and reigned for three years before dying. By that time, the papacy had lost its importance.

- Louis III was crowned in 901 but deposed in 905 by Berengar of Friuli.

- When Berengar died in 924, the Crescentii, a powerful Roman family, entered the succession.

- As a result, the empire that was created faded away as it became increasingly ineffective.

The Ottoman Empire

- In Italy, the empire associated with the papacy was disintegrating. The empire’s Frankish tradition was viewed as an expression of power and hegemony over various countries.

- Six years after his invasion of Lotharingia in 869, the West Frankish king Charles II the Bald was proclaimed emperor and Augustus. He now ruled over two kingdoms.

- Furthermore, after defeating the Hungarians in 933, the victorious Henry I was crowned as the first Saxon king of Germany. In 955, his son met the same fate as a result of the Battle of Lechfeld.

- Given the anarchic state of Italy, the Saxons hoped to succeed Frankish inheritance.

- Otto I ascended to the East Frankish throne in 936 after being recognised as Charlemagne’s true heir. Otto appointed churchmen as ministers and established missionary bishoprics on the Elbe River in the hope of spreading Christianity among the Wends.

Territory of the Holy Roman Empire in 962 - He led the Carolingian Louis IV of France in the West while also strongly supporting the young Burgundy king Conrad, who remained in power due to Otto.

- Otto surprised Italy in 951 by marrying the late king’s widow and forcing the newly crowned king, Berengar of Ivrea, to take over his kingdom.

- Otto returned to Italy after ten years after learning that Berengar was on the verge of seizing control of Rome. Otto was crowned emperor in 962 by Pope John XII.

- As in previous years, the pope made the immediate coronation due to his need for protection. However, during Otto’s time, the titles Augustus and Emperor were rarely given because they were less significant, so the protection that the pope expected was rarely extended to the Roman church. The empire’s territories shrank as well. Instead, the so-called empire referred to a union of Germany and northern Italy under a single rule.

- The Ottonian emperors had no desire to conquer the world or even challenge the Byzantine emperors. Nonetheless, the Byzantine Empire sought to expand and reconquer.

- Otto II declared himself Roman Emperor, in contrast to Otto I, who had no claim to the title.

- During Conrad II’s reign, the introduction of the title ‘king of the Romans’ was reinforced before the coronation of the emperor-elect, and the same would apply to his designated successor.

- Otto III, who was crowned in 996, formed a new synthesis of Roman, Carolingian and Christian ideas to combine into an imperial idaea during his reign. He designated Rome as his capital, and the pope as his lieutenant in spreading Christian sovereignty. However, Otto III lost Rome before he died, despite the fact that the close subordination of the pope and emperor remained from Otto I’s reign until Henry III’s.

The Investiture Controversy

- The papal theory of the empire was developed in the ninth century. It was revived with revisions to its foundations during the papacy of Gregory VII (1073-1085). However, it resulted in a conflict known as the Investiture Controversy, which lasted from 1076 to 1122 and focused on the issue of whether lay overlords had the power to take bishops and abbots into their domains. The real issue, however, was the emperor’s position in Christian society and his relationship with the papacy.

- Pope Gregory VII began the assertion of legitimately deposing emperors with the authority of his imperial insignia, with no one to judge him. This was interpreted as the pope’s assertion of superiority rather than independence.

- The pope demands that the emperor respond truthfully to God.

- Henry IV refused to accept the pope’s interference and persuaded his bishops to excommunicate Pope Gregory VII, whom he addressed as ‘Hildebrand’, ignoring the papacy.

- As a countermeasure, he declared Henry IV’s deposition and excommunicated him with the authority of the pope. He also invalidated his oaths of loyalty to Henry’s throne.

- The pope defeated the opposition, leaving the king with almost no political support.

- This compelled the king to undertake the well-known Walk to Canossa in 1077, after which his excommunication was lifted as retribution for his humiliation.

- Rudolf of Swabia, the newly elected king, was defeated by Henry. Nonetheless, Henry faced new uprisings, a new excommunication, and even the rebellion of his sons.

- Henry V, his second son, died. This prompted him to sign the Concordat of Worms in 1122 with the pope and the bishops, putting an end to the struggle over investiture.

- The conflict still limited the ruler’s authority over the Church.

The Empire in Modern Times

- The empire became a pivotal figure in German history. It primarily influenced the thinking of modern German rulers that there was a sense of belonging to a multinational empire in the Habsburg lands. Several emperors attempted to reclaim some of the old imperial constitutional powers. The empire’s leadership of Christendom was advantageous in the face of the Turks. Furthermore, the empire’s institutional role was gradually fading. Berthold of Henneberg, the elector of Mainz in 1495, failed to impose an imperial reform project.

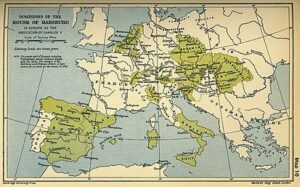

Dominions of the Habsburg in 1556 - When Charles V sought to restore the empire’s single ruler, he seemed to be speaking in impossible terms.

- Despite having previously won the Roman Catholic Church against the Reformation, Charles ruled an empire that was neither in the spirit of nor a revival of the medieval one.

- He accepted the Peace of Augsburg in 1555 but failed to take responsibility for it within a year.

- While Germany was divided into two religious camps, the emperor was not powerful enough to bring them together.

- The imperial crown, though theoretically elective, was inheritable in the Habsburg dynasty of Austria, resulting in disunity of interests between emperor and empire.

- From 1556, the empire gradually declined in importance.

- No other emperor attempted to reestablish a strengthened central authority after the Thirty Years’ War like Charles V.

- Even after its downfall under Francis II in 1806, the small knights and noblemen of Western Germany remained ardent supporters. They claimed that the empire shielded them from princely absolutism.

- The French Revolution also boosted nationalism, which later became an anachronism.

- The Holy Roman Empire came to an end, but the debate over the scope and nature of its influence raged on.

Image Sources

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fc/Greater_coat_of_arms_of_Leopold_II_and_Francis_II%2C_Holy_Roman_Emperors.svg/800px-Greater_coat_of_arms_of_Leopold_II_and_Francis_II%2C_Holy_Roman_Emperors.svg.png

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b5/Aachen_Domschatz_Bueste1.jpg/330px-Aachen_Domschatz_Bueste1.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/1a/Ludwik_I_Pobo%C5%BCny.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/c2/HRR.gif

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/be/Dominions_House_Habsburg_abdication_Charles_V.jpg/413px-Dominions_House_Habsburg_abdication_Charles_V.jpg