Download William I: William the Conqueror Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach William I: William the Conqueror to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Table of Contents

Add a header to begin generating the table of contents

Summary

- Who was William the Conqueror?

- What was his connection to the English throne?

- Events leading to the Battle of Hastings and its result.

- The challenges faced by William I as king of England.

- Legacy as the first Norman King of England

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about William the Conqueror!

- Nicknamed ‘William the Bastard’ for being the illegitimate son of Duke Robert I of Normandy to a French woman named Herleve, William became the King of England in 1066 after his successful battle against King Harold II and invasion of England.

- On January 5, 1066, the death of Edward the Confessor, his distant cousin, resulted in competing claims over the English throne.

- William was known to be a skilled military man who led his cavalry against foreign invaders. His victory during the Battle of Hastings gained him control over England. Leading both Normandy and England, William faced resistance and revolts, wherein most were harshly subdued.

- On September 9, 1087, he died after suffering from a major injury. He was buried in St. Stephen’s monastery. His son, William II Rufus, took over the English throne, while his other son, Robert, ruled Normandy. It was only in 1100 when England and Normandy were ruled by a single monarch, Henry I.

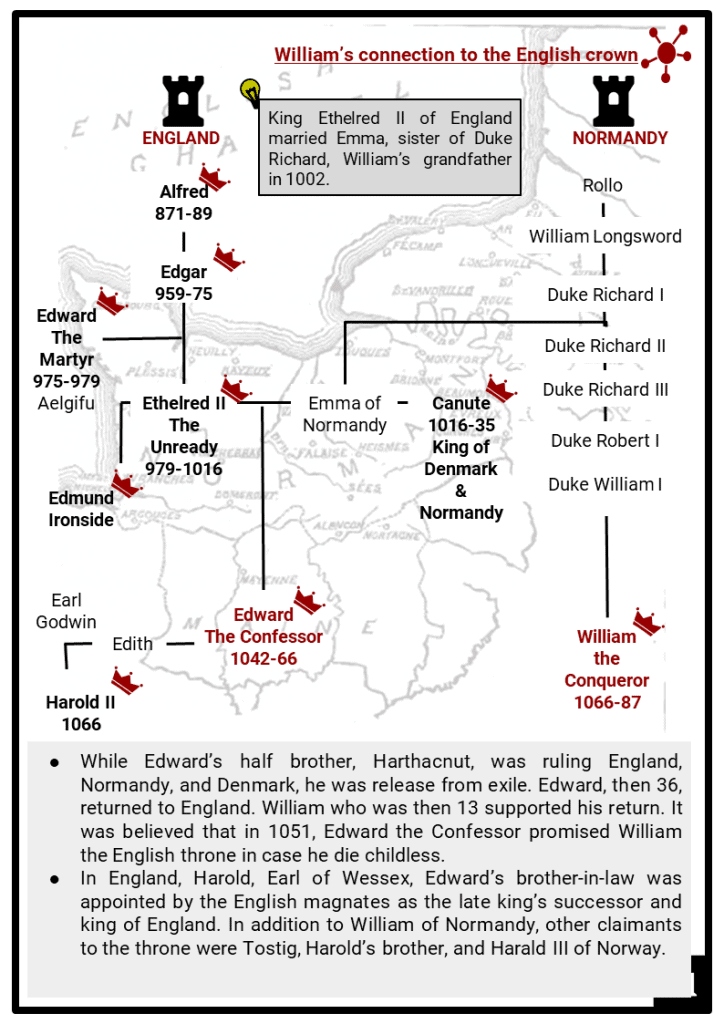

William’s connection to the English crown

- While Edward’s half brother, Harthacnut, was ruling England, Normandy, and Denmark, he was release from exile. Edward, then 36, returned to England. William who was then 13 supported his return. It was believed that in 1051, Edward the Confessor promised William the English throne in case he die childless.

- In England, Harold, Earl of Wessex, Edward’s brother-in-law was appointed by the English magnates as the late king’s successor and king of England. In addition to William of Normandy, other claimants to the throne were Tostig, Harold’s brother, and Harald III of Norway.

The Battle of Hastings

- On September 28, 1066, William and his troops landed at Pevensey, England. After seizing England’s southeast .

- On October 14, 1066, King Harold positioned his exhausted army on Senlac Hill near Hastings. The battle ended in a decisive Norman victory. According to legend, King Harold was said to have been shot in the eye with an arrow.

- By Christmas of the same year, William reached London and was crowned as the first Norman King of England. His invasion of England led to the end of the Anglo-Saxon era of English history and the beginning of French influence in the kingdom.

As king of England

- In order to successfully carry out the conquest, William had to ensure that opposition to his rule was removed.

- To do this, William encouraged people to support him, or powerfully deter opponents from acting.

- William’s approach to government was, therefore, key in order to secure both his position as king and the inheritance of his heirs.

- After the Battle of Hastings, William waited to see if the earls and lords of England would submit to him. They did not; they were planning what to do next, and many of them supported Edgar Aetheling.

- The English earls’ initial support for Edgar Aetheling soon began to fade. They were worried that Edgar’s young age would be a drawback in his ability to rule effectively.

- William’s brutality in the south also convinced many of them to support the Duke of Normandy, believing that this might allow them to maintain some power and influence.

- In December, Edgar and many of the English nobles travelled to Berkhamsted and swore loyalty to William. This is known as the Submission of the Earls.

- William also attempted to secure the support of the English lords through marriage alliances. Earl Waltheof married William’s niece and discussions were had about a possible marriage between Earl Edwin and one of William’s daughters.

- William dealt harshly with descendants of those who had died at Hastings, taking away their land and refusing to allow heirs to inherit their titles. This allowed William to give their land and titles to Normans instead, meaning that some of the most powerful people in England were Normans who William could rely on to support him.

- By March 1067, William felt secure enough to return to Normandy, leaving his half-brother, Bishop Odo of Bayeux, and his loyal Norman supporter, William Fitz Osbern (who had been made Earl of Hereford) running England on his behalf.

Problems after the Hastings

- Although many English lords had sworn loyalty to William, they still resented the Norman invasion.

- They were also unhappy at the fact that Normans were being given extensive land and titles.

- As the Norman Conquest of England developed, people were given new reasons to resent their new rulers. In many areas, castles were built and, in order to fund them, taxes were levied on the local population.

- Bishop Odo and William Fitz Osbern were also unpopular and were seen as responsible for allowing Normans to plunder and commit acts of violence on the English.

- Small revolts began to take place in 1067, resulting in the deaths of some Normans.

- The people of the region were unhappy with the taxes being levied by the new king and were also being encouraged to rebel by Gytha, Harold Godwinson’s mother.

- William faced an on-going challenge of subduing parts of the kingdom, especially Wales.

- His solution was the Marcher lords, who were nobles appointed by William to guard the border known as the Welsh Marches.

- Among the greatest Marcher Lords included the earls of Chester, Gloucester, Hereford, Pembroke and Shrewsbury.

- The Anglo-Norman lordships in this area of the country were different to English lordships because they were smaller and Marcher lords ruled by their own law, much like a king, while English lords were still accountable to the king.

- Marcher lords administered laws, waged war, established markets in towns, and maintained their own chanceries.

- The Welsh Marches also had the densest concentration of motte-and-bailey castles.

William’s Legacy as King

- One of William’s first actions upon arriving in England was constructing a large number of castles. Though England had defensive fortifications prior to the Norman Conquest, these burgs or burhs, were typically Roman fortifications and often adapted by the Anglo-Saxons.

- Norman fortifications differed, however, as they became private fortified residences.

- CASTLES

- Castles were vitally important to William in allowing him to take control of England after the Battle of Hastings. Despite being fairly simple constructions, the motte-and-bailey castles that were established meant that potentially rebellious Anglo-Saxons were presented with a powerful symbol of Norman strength and authority.

If a rebellion were to occur, the castles built by William also gave protection to the Norman soldiers within. - Over the next few years, many of these wooden castles were replaced with stone keeps in order to make them likelier to last and less easy to destroy. One such example was Tamworth Castle, in the former Saxon earldom of Mercia in the Midlands.

- Castles had administrative and economic functions too. Often built near rivers, roads and harbours, the castle served to control the movement of people and trade through tolls and taxation. Castles also had craftsmen and merchants to serve those who lived in and around the fortifications.

- Castles were vitally important to William in allowing him to take control of England after the Battle of Hastings. Despite being fairly simple constructions, the motte-and-bailey castles that were established meant that potentially rebellious Anglo-Saxons were presented with a powerful symbol of Norman strength and authority.

- LAND SURVEY

- As king of England, William I ordered the surveying of all English lands and holdings. In December 1085, as commissioned by the new king, wealth and assets throughout England were assessed by the Royal commissioners in order to raise taxes and pay the army.

- In 1086, the Domesday Book was first published containing records for 13,418 settlements located south of the Ribble and Tees rivers. England was then divided into 7 regions called circuits. About 3 to 4 commissioners were sent out to question a jury of barons and villagers. In addition to land assets, records of cows, pigs and fish were recorded.

- The title ‘Domesday Book’ was adopted in the late 12th century in reference to the Last Judgement as described in the Christian Bible.

- There were two volumes of the Domesday Book. The first volume, called the Great Doomsday, contained the records of all counties surveyed except Norfolk, Essex, and Suffolk. The second volume called ‘Little Domesday’ covered these three counties, but it was not added to the first volume.

- FEUDALISM

- Feudalism was a socio-political and economic system utilised in Western Europe during the Medieval Period. It was characterised by a king’s ownership of vast land and the distribution of it to people in exchange for services. The feudal hierarchy encompassed all social class levels.

- During the rule of William I, he modified the Anglo-Saxon hierarchical system already in existence. The initial move was to claim all land in England. About a fifth was retained for his own use, while another 25% went to the church.

- The rest was distributed to about 170 tenants-in-chiefs called barons. Those barons were the ones who helped him during the Battle of Hastings. Under William’s authority and power, about 6,000 manors in England were distributed.

- The term feudal was derived from the word fief, which refers to tenancy of a piece of land under a certain condition, usually of service.

- Ceremonies were held as William granted each baron land. Barons then pledged their oath of loyalty to the king for the rest of their lives. Barons then carried out the same ceremony with their knights.

- The person who received the fief was called a vassal, while the person who gave the fief was his lord.

- Prior to being granted a fief, a person had to be a vassal, which took place through a commendation ceremony.

- The ceremony was composed of an act of homage and an oath of fealty.

- The act of homage was a bond of tenure between the lord and the vassal in which the receiver of the fief would promise to fight for the lord, whilst the lord would protect the vassal. The oath of fealty denoted the vassal’s fidelity to his lord.

- Manorialism, or the manor system, was a socio-political and economic system during the Medieval Period in which peasants were dependent on the piece of land granted to them by lords.