Download Peasants Revolt Timeline Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach Peasants Revolt Timeline to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Table of Contents

Add a header to begin generating the table of contents

Summary

- Background of the Peasants Revolt

- Chronological order of events during the Peasants Revolt

- Key figures involved in the Peasants Revolt

- Consequences of the peasants’ failure in the Peasants Revolt

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about Peasants Revolt!

- The Peasants Revolt was one of the most dramatic events of the first quarter of the sixteenth century. This great failed attempt to free the peasantry, who were shaken, aside from in South and Central Germany, part of Lorraine and Alsace, provoked passionate controversies about its origins, the interpretation of its nature and its exact consequences.

- The origins of the Peasants Revolt were twofold: on the one hand there were the social tensions of the end of the fifteenth century, on the other hand, the fermentation of spirits. Social tensions were accentuated by the demographic upsurge, the rise of prices, the new ways of living that had set in and tended to crystallise the opposition of the classes, peasantry, and nobility vis-a-vis the urban residents, the clergy and the princes.

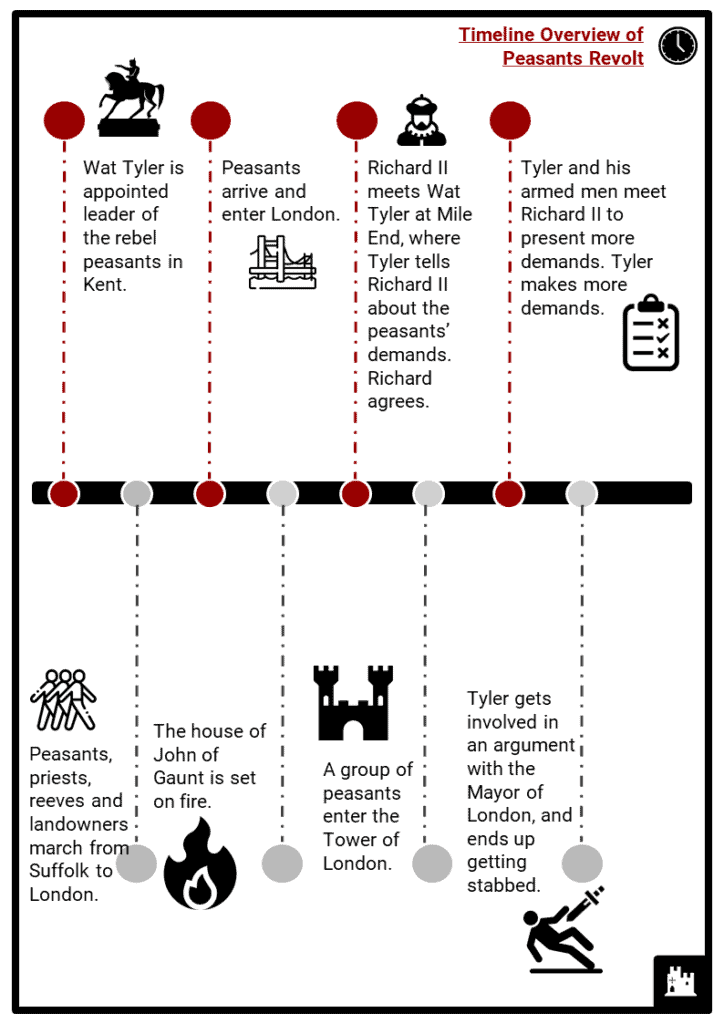

Timeline Overview of Peasants Revolt

- Wat Tyler is appointed leader of the rebel peasants in Kent.

- Peasants arrive and enter London.

- Richard II meets Wat Tyler at Mile End, where Tyler tells Richard II about the peasants’ demands.

- Richard agrees.

- Tyler and his armed men meet Richard II to present more demands. Tyler makes more demands.

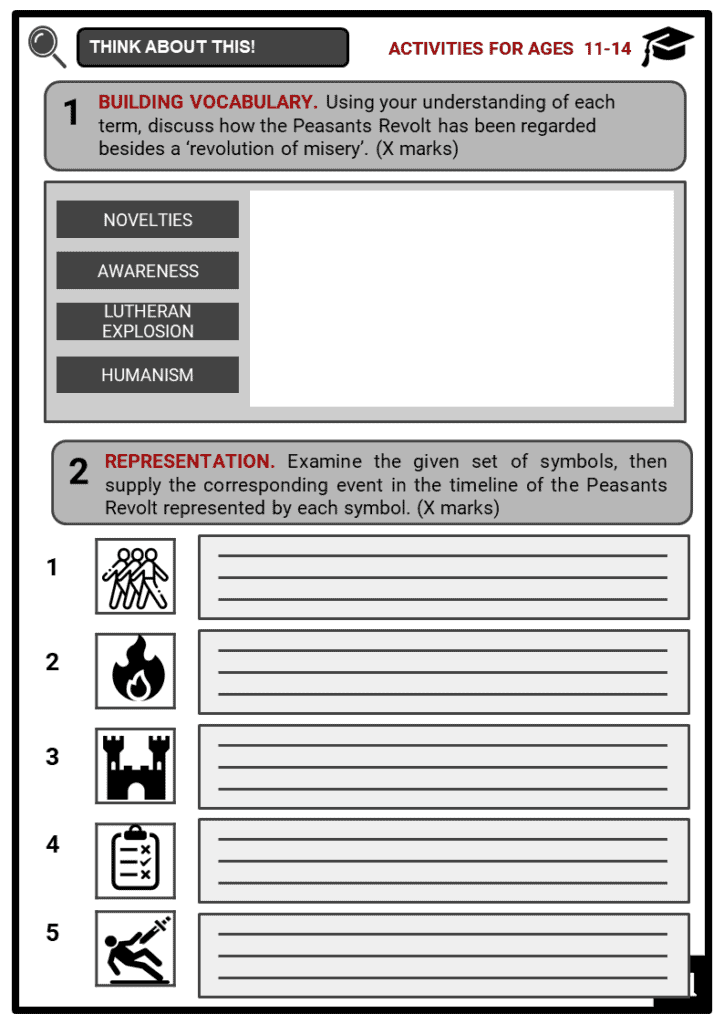

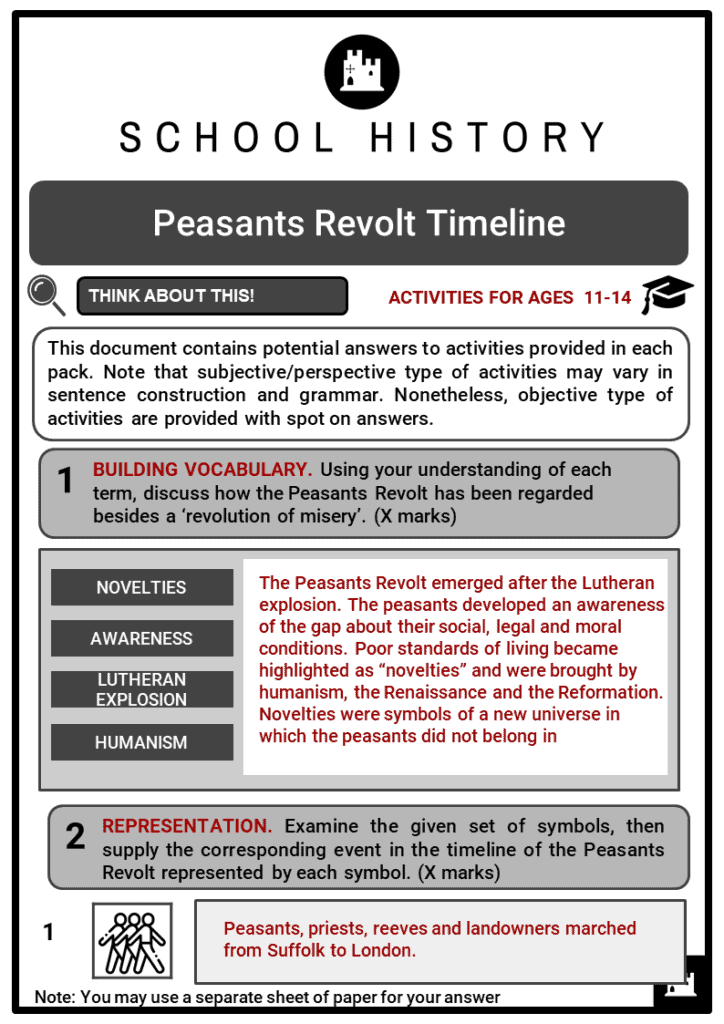

- Peasants, priests, reeves and landowners march from Suffolk to London.

- The house of John of Gaunt is set on fire.

- A group of peasants enter the Tower of London.

- Tyler gets involved in an argument with the Mayor of London, and ends up getting stabbed.

Peasants Revolt Background

- This revolt was not only a march by the peasants but also by local priests, small landowners and reeves.

- To some people, the Peasants Revolt was a revolution of misery. Overwhelmed by debts, royalties, chores, the increasing fragmentation of property, attacks on the community and the high cost of living, the first erratic bursts of peasant class revolts were rampant following the Lutheran explosion. Favoured by the increasing number of idle people – often former soldiers – the revolt found allies everywhere. From the leaders of nobility, the knights, to those affected by the progress of urban capitalism.

- Reeves are the chief magistrates of an Anglo-Saxon town in medieval England.

- A second school interprets the event as “awareness” related to the awakening of spirits. The peasants rose, not because they were in misery, but because of the gap between their relatively prosperous economic situation and their social, legal and moral condition.

- Poor standards of living became highlighted as “novelties” and were brought by humanism, the Renaissance and the Reformation. Novelties were symbols of a new universe in which the peasants did not belong. By the widespread reception of Roman law, the use of the written law, new forms of interest-bearing loans, the role of seigniorial and municipal “officials”, and the contempt of the peasant, emerged.

- There were two stages in the course of the conflict: a fight “for the old custom” (which was expressed by some references to an alleged draft constitution of the German Emperor Sigismund taken up by Frederick III); then, and in relation to religious novelties, the spread of information and books multiplied by printing, the attack on the Roman authorities led by Luther, a fight for the equality of men before God and between them, within a new society, based on the Gospel alone.

An explosion of revolts

- The war presented a host of simultaneous episodes, but without any positive or apparent links, the analysis of which is made difficult by the lack of uncommitted sources, the partiality of historians, and the attraction exercised by certain chiefs, apostles and martyrs.

- Multiplied after 1480, the precursor identity was symbolised by a name, the Bundschuh. In 1476, John of Niklashausen announced, in the name of Our Lady, the suppression of the clerical or secular authorities. In 1493, led by a burgomaster of Sélestat, Ulmann, broke out in Alsace the first Bundschuh, but it was quickly repressed; following in 1502 those of Bruchsal, in 1513 of Lehen in the Breisgau, the “movement of the poor Konrad”

- in Wurttemberg. At the same time, the peasants of Rouffach were agitated; in 1517, led by Joss Fritz, the movement involved both sides of the Rhine.

- In the same year, Luther launched his ninety-five theses on indulgences at Wittenberg and set off an irreversible process; in Zwickau in Saxony, Thomas Münzer in 1520 gathered around him clothmakers, miners and labourers, taking over the millennial dream of Joachim de Flore, finding in Prague the teaching of Jean Huss (Jan Hus) and settling in Allstedt. In 1522, the knights Franz de Sickingen and Ulrich de Hutten were crushed. All Germany was in turmoil: before the alliance of the young Charles V, elected in 1519, with the Pope and the Fuggers, the hopes of a

reform coming from above vanished. - The first victories were followed by princely repressions. In the Black Forest and Swabia, the mechanism was exemplary. An initial incident, the picking of strawberries ordered by the Countess Lupgen, led to the election of a leader, Hans Muller, a former soldier, at the appearance of the black, red and yellow flag, and the program: the twelve articles.

- The Twelve Articles is the statement of principles declaring the peasants' demands of the Swabian League during the German Peasants' War of 1525.

The Revolt of the Peasants in England in 1381

- In 1381, a vast rebel army ransacked the Tower of London, burned the palaces and assassinated government officials. What caused this popular explosion: adverse socio-economic conditions or an admitted hatred towards King Richard II? Return of the revolting peasants, and the Hundred Years War with France.

Meetings between those revolting and their sovereign

- One of the leaders of the uprising, Chaplain John Ball, called to the rebels camped on the southern bank of the Thames at Blackheath, “the time is given to them by God” to get their freedom. This should not be a bloody revolution, but a coup d’etat. “The archbishop with the great men of the kingdom will have to be removed …”, said Ball, then also: “… the lawyers and the judges will have to be expelled from our lands”.

- The royal party still hope to avoid a large scenario by getting rid of rebels before they enter the city. The agitators agree to negotiate with the Blackheath king.

- Richard II cautiously approaches the river aboard a barge but does not advance further than Rotherhithe. The rebels have asked the authorities that 15 of the king’s advisors, including Gaunt, Sudbury and Hales, be beheaded immediately. No negotiation seems possible, and the king’s party withdraws into anxiety.

- In a few hours, the crowd crosses the bridge to enter the city. During a night of confusion and fear in the Tower, Richard II’s counsellors discuss their plan of action. Some are in favour of a violent response. Hundreds of knights are established in London, and the mayor, William Walworth, wants to organise a militia.

- However, the loyalty of Londoners cannot be known for sure, the streets are not a place for a fierce battle and the risk of loss remains too great. The Earl of Salisbury would have advised the king to negotiate with the rebels and grant them whatever they wish, for if the authority started an armed response he could not control, England would be lost.

- As a growing crowd encircles the Tower of London, the king makes his decision. He has a charter written and orders a man to get up and read it. This promises the rebels pardon for “all their illegal offences”, provided they return home in peace. The authorities send them a letter detailing their grievances.

- The crowd take this low offer with derision. The rebel counsellors renew their request that the king himself come and talk to them.

- Richard sends messengers to formalise a meeting on the morning of 14 June in Mile End: a place at a certain distance from the city and far from its streets.

- The King, Mayor Walworth, and many others go there, leaving Simon Sudbury, Archbishop of Canterbury and Lord Chancellor of England, and Lord Treasurer Robert de Hales alone in the Tower of London.

Causes and consequences of the peasant failure

- Mystic, political, economic, social and military realities mingle closely within the movement.

- As early as 15 March, 1525, in the “twelve articles”, the Swabian peasants gathered at Memmingen demanding the right to choose their parish priest and to pay only the lawful tithe, the emancipation of serfdom, the freedom of hunting and fishing, that of the woods, the limitation of the chores, a suitable salary, moderate cents, preserved communes, the abolition of the mortuary and a life in conformity with the Gospel. In April, Luther implored the nobility and the peasants to renounce violence.

- The programme of Münzer developed a radical revolution: a community of goods, work obligation for all, suppression of all authority. In Heilbronn, capital of the insurgents, Hipler developed a kind of German constitution. Faced with the successive destructions and the threat of social revolution, Luther launched his pamphlet against the plunderers and assassins of peasants, which justifies the atrocities of repression in advance.

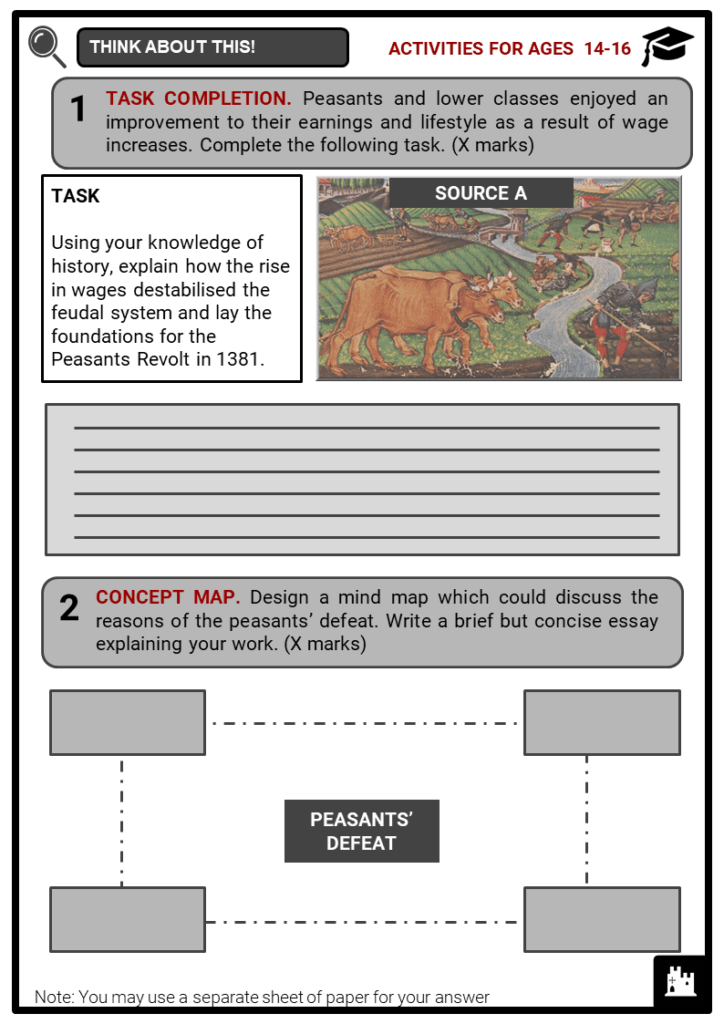

- The peasants had their size, the effect of surprise, mobility and knowledge of the ground. Their armaments and their leaders were not inferior to those of the lords, even as regards the artillery.

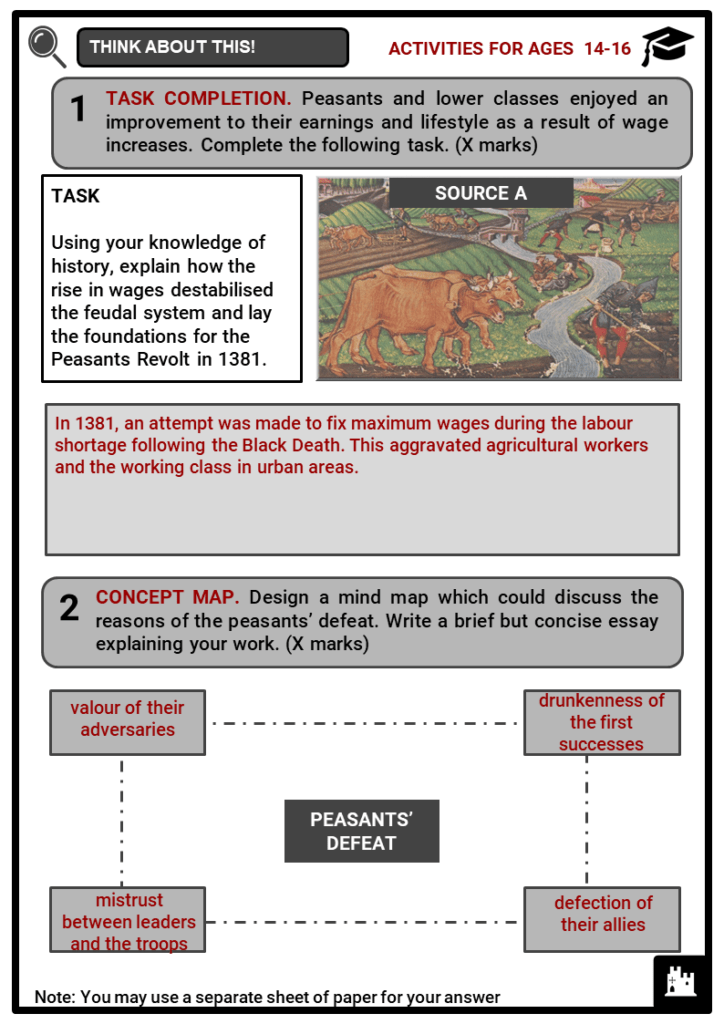

- Their defeat was due…

- to the valour of their adversaries (Truchsess);

- to the drunkenness of the first successes;

- to mutual mistrust between the leaders and the troops,

- to the defection of their allies; and finally

- to the lack of cohesion of the whole in the face of the mercenary troops, lansquenets in the pay of the princes returned from Italy.

- The repression, individual or collective, was atrocious.

- Among the consequences of the peasants’ failure, some are immediate:

- considerable mortality difficult to quantify;

- destruction of convents, castles, farms and villages;

- the others are further afield:

- the maintenance of the medieval legal and economic regime;

- the weakening of the clergy except in preserved regions such as the Bavarian Catholic Church;

- the disappearance of the nobility and the reinforcement in the towns of the patrician regime re-established everywhere;

- the rise of the power of the princes

- The latter appear as true winners of this lamentable tragedy that marked the German conscience for centuries.

Image sources: