Tokugawa Japan Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Tokugawa Japan to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Table of Contents

Add a header to begin generating the table of contents

Summary

- The Shoguns

- Background & Rise of Tokugawa Shogunate

- Tokugawa Japan and Foreign Influence

- Society Under the Tokugawa Shogunate

- The Beginnings of Change

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about Tokugawa Japan!

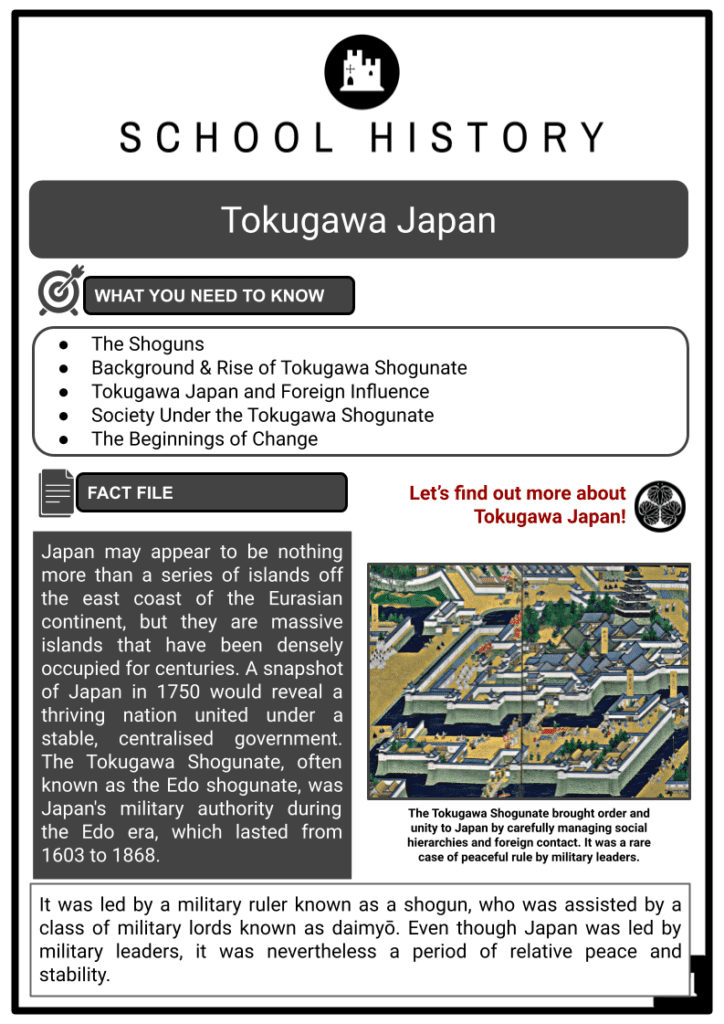

- Japan may appear to be nothing more than a series of islands off the east coast of the Eurasian continent, but they are massive islands that have been densely occupied for centuries. A snapshot of Japan in 1750 would reveal a thriving nation united under a stable, centralised government. The Tokugawa Shogunate, often known as the Edo shogunate, was Japan's military authority during the Edo era, which lasted from 1603 to 1868.

- It was led by a military ruler known as a shogun, who was assisted by a class of military lords known as daimyō. Even though Japan was led by military leaders, it was nevertheless a period of relative peace and stability.

The Shoguns

- The shoguns maintained order in a variety of ways, including trade, agriculture, foreign affairs, and even religion.

- Because the Tokugawa shoguns tended to transmit power down dynastically from father to son, the political system was stronger than in previous ages. They also moved away from the past, literally, by establishing a new capital in Kyoto, which was the former seat of imperial sovereignty.

- It was once known as Edo, although you're probably better familiar with the name Tokyo. It was merely a modest seaside fishing village before the shoguns made it their governmental seat.

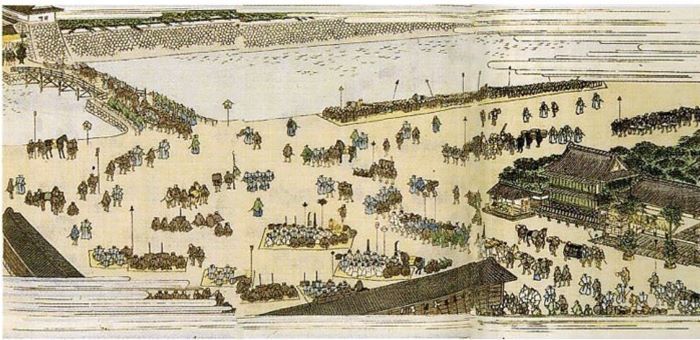

- The shoguns built well-planned mechanisms in this new city to maintain control. The shoguns obliged the daimyō to swear allegiance to the shogunate (the shogun's administration) and to maintain houses in the capital every other year. Because the regional military lords already had enormous houses back home in the provinces, this was a significant move. This configuration provided a number of functions. It kept the daimyō close, and when they went to the provinces, they had to leave their families in the imperial homes.

- By taking control of the country's production and distribution, the shoguns solidified their power. And it worked, because agriculture and commerce thrived during the Tokugawa.

- They implemented improved farming techniques in rural areas. Land surveys were also utilised to track and enhance farming production, providing a reliable food supply.

- The construction of a comprehensive highway network connecting the provinces with the capital also aided city life. This made it easier for the daimyō to travel between provinces and the capital and move resources. The Japanese population increased during this time.

Background & Rise of Tokugawa Shogunate

- Power was decentralised in Japan during the 1500s, after nearly a century of conflict between contending feudal lords (daimyō). Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543-1616) quickly consolidated authority from his well guarded fortress at Edo following his victory in the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600 (now Tokyo).

- After a century of battle, the Tokugawa dynasty set out to rebuild order in social, political, and international matters. Ieyasu established a governmental structure that was cemented by his two immediate successors, his son Hidetada (who governed from 1616-23) and grandson Iemitsu (1623-51), which connected all daimyos to the shogunate and restricted an individual daimyō from accumulating too much land or influence.

Tokugawa Japan and Foreign Influence

- The Tokugawa dynasty acted to exclude missionaries and eventually placed a complete ban on Christianity in Japan, fearful of foreign meddling and colonialism.

- There were an estimated 300,000 Christians in Japan at the start of the Tokugawa period, but Christianity was forced underground after the shogunate brutally suppressed a Christian rebellion on the Shimabara Peninsula in 1637-1638.

- Confucianism, a rather conservative religion with a strong emphasis on loyalty and responsibility, was the main faith of the Tokugawa period.

- The Tokugawa shogunate forbade trade with Western nations and prohibited Japanese merchants from trading overseas in order to isolate Japan from harmful foreign influence.

- Japan was effectively cut off from Western nations for the next 200 years after the Act of Seclusion (1636). At the same time, it maintained tight ties with neighbouring Korea and China, reaffirming an East Asian political system centred on China.

Society Under the Tokugawa Shogunate

- The Tokugawa Shogunate was known for bringing order and unity to Japan, in part by maintaining severe social structures.

- The Confucian concept of society being divided into four social classes influenced this in various respects. They were warrior, farmer, artisan, and merchant from the top-down. The warrior class included the shogun, daimyō, and samurai.

- Each class served a specific purpose and was supposed to contribute to social order.

- The warrior class did not mix much with the other classes because they lived in distinct portions of the cities and villages. Peasants also had limited geographic and social mobility; they had to acquire permission to relocate or travel.

- Warriors and farmers were thought to have made the most significant contributions. Because food was so important, farmers were valued more than artisans. Merchants were regarded as parasites because they produced nothing, and money deals were considered immoral by Confucius.

- The social hierarchy, although rigid in theory, did not always operate in practice. Movement restrictions were not routinely implemented. Some samurai were quite destitute, whereas merchants were able to amass vast fortunes and political power.

- Peasant revolts, though usually brutally defeated, also kept the elite's authority in check to some extent. According to some recent research, peasants may have even forced daimyō to decrease taxes.

- Confucian values also influenced women's lives and family structures. Filial piety, or respect for elders and ancestors, was emphasised. To their male family members, women were expected to be submissive. Women gained more authority in their houses as they had more children and grew older.

- However, the lives of women in different social classes were very different. Peasant women, for example, frequently toiled in the fields with their male family members, and gender distinctions were less strict.

- Women in the lower classes were more likely to divorce and have relationships outside of marriage than upper-class women, for whom marriage was typically a key political ally. Outside of marriage, men of all classes were generally more liberated than women.

The Beginnings of Change

- Nonetheless, the Japanese interacted with European cultural concepts as well. Despite the fact that European publications were limited for a period, many Japanese intellectuals used Dutch sources to supplement their knowledge, notably in science and technology.

- In reaction to global influences, Japan's economy gradually changed. Despite traditional beliefs that money is sinful, money had become increasingly important in Japanese culture. This had an impact on government employees' salaries, which were formerly paid in predetermined amounts of rice.

- The merchant class acquired power as trade, industry, and banking flourished. Revaluing the currency, regulating money exchanges, modifying the tax system, and creating merchant guilds were all key government reforms.

- While the Japanese did protect their society and economy from foreign influences, they did engage in trade and cultural exchange.

- Though the shoguns attempted to control these transactions, restrictions gradually eased. Meanwhile, they oversaw a society with an extraordinarily high quality of living for the time, whether compared to neighbouring states or European societies.

- Shoguns maintained this standard of living for over two centuries while avoiding major warfare—a remarkable achievement for a society ruled by military rulers.