Download Feudalism Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach Feudalism to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Table of Contents

Add a header to begin generating the table of contents

Summary

- Origins and development of the feudal system

- Features of the feudal system

- Decline of feudalism

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about Feudalism!

- Feudalism was a political, economic and social system that flourished in Western Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. It had its roots in Germanic and Roman traditions. It was characterised by a king’s ownership of vast land and the distribution of it to people in exchange for services. Its two principal institutions were vassalage and the fief. With the rise of towns and commerce and the decline of local organisation, feudalism gradually broke down in the continent. However, many of its remnants persist and still influence Western European institutions.

Origins and development of the feudal system

- Feudalism was a socio-political and economic system utilised in Western Europe during the medieval period. It developed as early as the 8th century and flourished between the 9th and 15th centuries.

- The bond of mutual loyalty between lord and vassal, which formed such an essential part of medieval feudalism, appears to have derived from the German comitatus described by Tacitus in 98 CE, the band of free fighting men associated with a prominent leader in an equal and honourable status.

- The companions followed their chieftain into battle, having sworn to fight to the death in support of him. In return, the chieftain looked after their welfare, gave them leadership, provided food, shelter and entertainment in times of peace.

- The Romans had long known a somewhat similar arrangement, in which clients commended themselves to a powerful patron, giving personal devotion in return for subsistence and protection.

- But this involved a definitely inferior status on the part of the client, and it was thus unlike the honourable relationship of vassalage which became a part of feudalism.

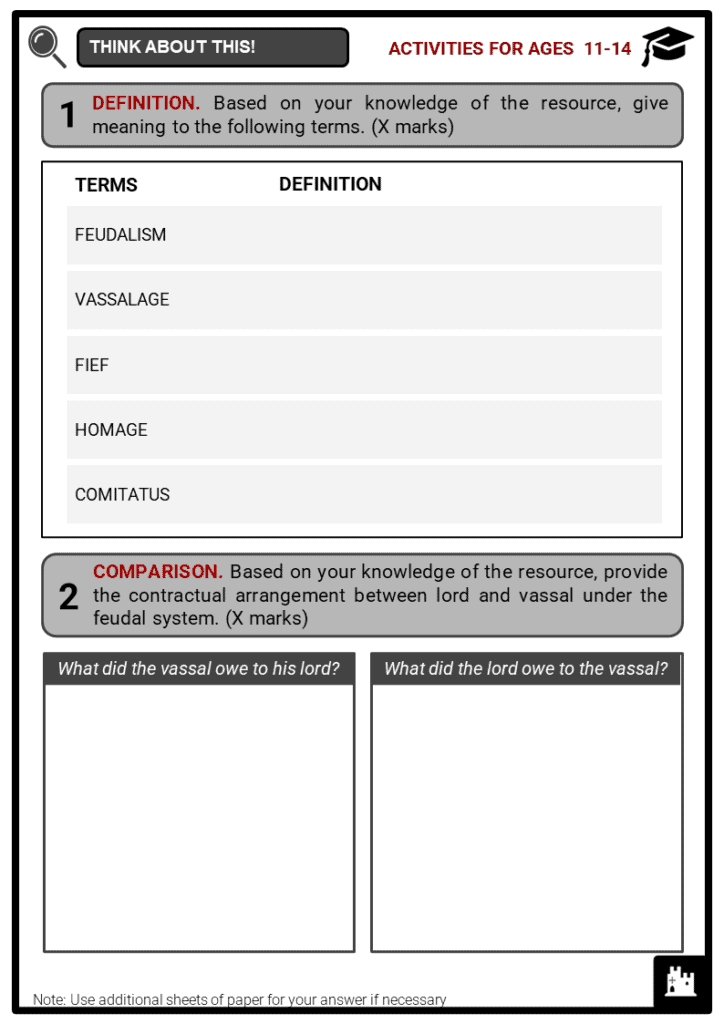

- During the economic and political decay of the later Roman Empire, clientage was often linked with landholding.

- Small farmers found it impossible to compete with the great estates, and many commended themselves to powerful landlords, giving up their lands and receiving back the right of their use under the lords’ protection.

- These relationships probably continued after the use of the Germanic kingdoms on the ruins of the Roman Empire in the West.

- In a predominantly agrarian economy, rights to land became the basis of wealth and power.

- The relations of personal dependency between lord and vassal, known as vassalage, was more and more associated with rights of land, termed the fief.

- An important step towards feudalism was taken by the Frankish king Charles Martel in the 8th century, in creating numerous military fiefs from lands which he took from the Church.

- Their holders became his vassals and were thus enabled to support themselves as mounted and heavily armed fighting men during wars.

- Private jurisdictions developed as the early Frankish rulers gave grants of immunity to various monasteries and laymen, by which the king’s officials were excluded from their lands.

- Thus, the lord of the land came to exercise the following public functions:

- Collecting taxes

- Holding court for his tenants and vassals

- Calling out the fighting men

- The processes were accelerated during the break-up of the Carolingian empire in the 9th century, when men looked in vain to weak central governments for protection and leadership, and turned instead to powerful local magnates, becoming their vassals and holding their lands as fiefs for them.

- The idea of kingship never entirely vanished, but the government and the administration of justice came to be exercised by various local authorities who had connections with the king.

- The counts and other royal officials took for their own use the lands and authority attached to their offices, and the great landlords everywhere seized the privileges of immunity.

- The kings acquiesced in this, finding it necessary, in the absence of money to pay salaries, to give fiefs of lands and revenues, and to try to bind their holders to themselves by homage.

- In turn, the royal vassals and churches with immunities gave part of their lands and functions to vassals of their own.

- Thus, a process of decentralisation went on by, in which the various powers of the state were divided among the feudal lords and churches.

- As the central authority became even weaker, the local authorities became practically independent princes, ruling and dispensing justice, and waging wars with their feudal armies.

- This system extended from France to Spain, Italy, Germany and England. Whilst the important features of feudalism were similar throughout, there existed definite national differences.

Features of the feudal system

- Feudalism was characterised by a king’s ownership of vast land and the distribution of it to people in exchange for services. It was intricately connected with the manorial system but it proved distinct from the latter. The feudal hierarchy encompassed all social class levels.

- The two principal institutions of feudalism were vassalage and the fief.

- Vassalage was a contractual arrangement between lord and vassal, established by a ceremony of homage in which the vassal kneeled and placed his hands between the hands of his lord, and swore to serve him faithfully.

- What did the vassal owe to his lord?

- The vassal owed to his lord loyalty, obedience, aid, counsel and court service.

- The pecuniary aids were due on special occasions, later restricted to the knighting of the lord’s eldest son, the marriage of his eldest daughter, and the payment of his ransom if he were taken prisoner.

- The vassal owed military service to his lord, eventually fixed at forty days in the year. He might have to supply several knights beside himself, according to the amount of land he held.

- This relationship lasted only during the lifetime of both parties.

- When one of them died, the acts of homage and investiture and the oaths of fealty had to be renewed.

- When the hereditary principle was supplemented, the son normally succeeded his father as a vassal of the lord, and received the fief on the same terms, although he was required to pay a sum of money called relief, in recognition of the fact that the fief belonged to the lord.

- If the new vassal was minor, he became a ward of his lord, who administrated the fief in his own interests until the boy came of age.

- Heiresses were also wards of the lord until they married, and the lords asserted the right to choose the husband, who would become their vassals.

- When a vassal died without heirs, the fief reverted to the lord as owner.

- Forfeiture to the lord resulted when the vassal failed to live up to his obligations if the lord were powerful enough to enforce it.

- Subinfeudation came about as vassals regranted part of their fiefs to men who then owed allegiance to them rather than to the original lord of the land.

- The consent of the overlord was theoretically required, but in practice, it was difficult to withhold it.

- This process might go on several times, as the sub-vassals granted fiefs to their men.

- Thus, a chain of landed dependency grew, from the king, who was theoretically lord of all the land, through the nobles, who were both overlords and vassals at the same time, down to the simple knight who had a fief and overlord but no vassals of his own.

- However, this development complicated the chain of personal dependence.

- As fiefs became alienable and heritable, it was not long before several were held by one vassal, who might thus have obligations to several lords.

- In France, an attempt was made to overcome this difficulty by the principle of liege homage to one lord, which was more binding than homage given to others.

- Even this became confused as vassals came to owe more than one liege homage through the process of inheritance or otherwise.

- Since there was no real definition of what constituted a breach of the sacred bond between lord and vassal, it was easy for either to find an excuse to declare it broken.

- Appeal to force was the only remedy, and private war was regarded as a privilege of the feudal nobles.

- Vassals began to regard their fiefs as hereditary possessions burdened with services and dues that they continually tried to restrict or evade altogether.

- As a result, the personal bond of vassalage was weakened. Feudalism, which had served to hold society together when the central authority almost disappeared, tended to be a system of organised anarchy.

- Despite efforts of the Church to restrict feudal warfare, little was accomplished until the royal power had grown strong and the king had become a national sovereign able to enforce justice, rather than the apex of a contractual system to whom only the great tenants-in-chief who held their lands for him owed direct allegiance.

- Impact of feudalism

- The feudal system became the basis of the medieval class system.

- Localised groups of communities which owed loyalty to a local lord were created.

- The feudal system enabled medieval kings to become more powerful with an army to raise in case of war.

Decline of feudalism

- Feudalism declined with the rise of towns and a money economy when land ceased to be the only important form of wealth. Money enabled feudal lords to pay their sovereign instead of performing military service. At the same time, with the development of new weaponries and methods of fighting, the nobles began to lose their position as an exclusive and privileged military class.

- Battles such as Courtrai, Crécy and Agincourt showed that the day of heavily armed knights fighting on horseback had passed.

- The feudal system became an anachronism in an age of gunpowder and capitalism.

- The weaknesses of European feudalism became evident by the 13th century, however, the system of interconnecting feudal obligations remained to be dominant in the continent until at least the 15th century.

- In England, France and Spain, the royal power advanced at the expense of the nobility.

- England was saved from the absolutism of the other two countries by the cooperation of the nobles and the other classes, and the development of Parliament for the limitation of the monarchy.

- But it was first necessary for the Crown to break down local powers and become strong, by the extension of its law and its machinery of administration, before a limited but efficient monarchy could evolve.

- Feudalism was abolished in England in 1662.

- Feudal customs and rights continued to be enshrined in the land laws of many nations including France, Germany, Austria and Italy until eliminated following the French Revolution. However, many remnants of feudalism still persist and influence Western European institutions.

Image sources:

- https://cdn.britannica.com/02/115002-050-C91498DA/Peasants-work-gates-town-painting-Breviarium-Grimani.jpg

- https://cdn.britannica.com/52/130352-050-8B473B8D/Charles-Martel-armour.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e5/Hommage_au_Moyen_Age_-_miniature.jpg/800px-Hommage_au_Moyen_Age_-_miniature.jpg