Easter Rising Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the Easter Rising to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- What was the Easter Rising?

- The Rising in Dublin

- The Rising outside Dublin

- Aftermath

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about the Easter Rising!

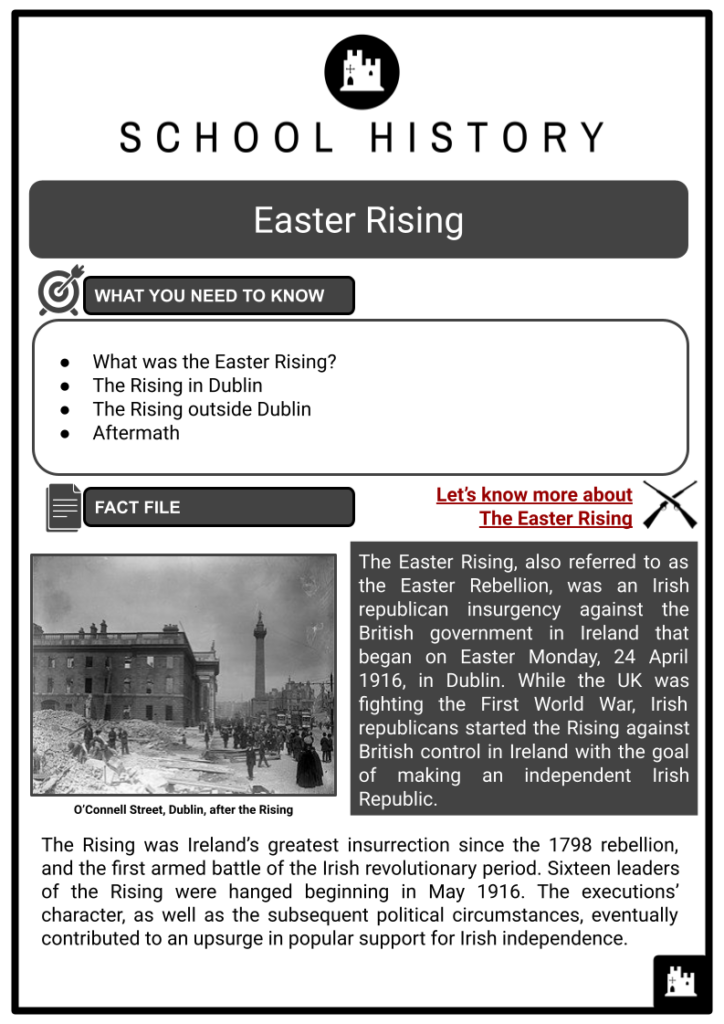

The Easter Rising, also referred to as the Easter Rebellion, was an Irish republican insurgency against the British government in Ireland that began on Easter Monday, 24 April 1916, in Dublin. While the UK was fighting the First World War, Irish republicans started the Rising against British control in Ireland with the goal of making an independent Irish Republic.

The Rising was Ireland’s greatest insurrection since the 1798 rebellion, and the first armed battle of the Irish revolutionary period. Sixteen leaders of the Rising were hanged beginning in May 1916. The executions’ character, as well as the subsequent political circumstances, eventually contributed to an upsurge in popular support for Irish independence.

What was the Easter Rising?

- The Easter Monday, 24 April 1916, Rising was organised by the Irish Republican Brotherhood seven-man Military Council and lasted six days. Members of the Irish Volunteers, led by schoolmaster and Irish language advocate Patrick Pearse, and aided by the smaller Irish Citizen Army, led by James Connolly and 200 women from Cumann na mBan, captured strategically important structures in Dublin and proclaimed the Irish Republic.

- The British Army crushed the Rising with significantly greater numbers and superior equipment. Despite sporadic resistance, Pearse agreed to an unconditional surrender on Saturday, 29 April. The country was placed under martial rule following the capitulation. Around 3,500 people were apprehended by British forces and transferred to internment camps or prisons in the United Kingdom. The majority of the Rising’s commanders were executed during court martial.

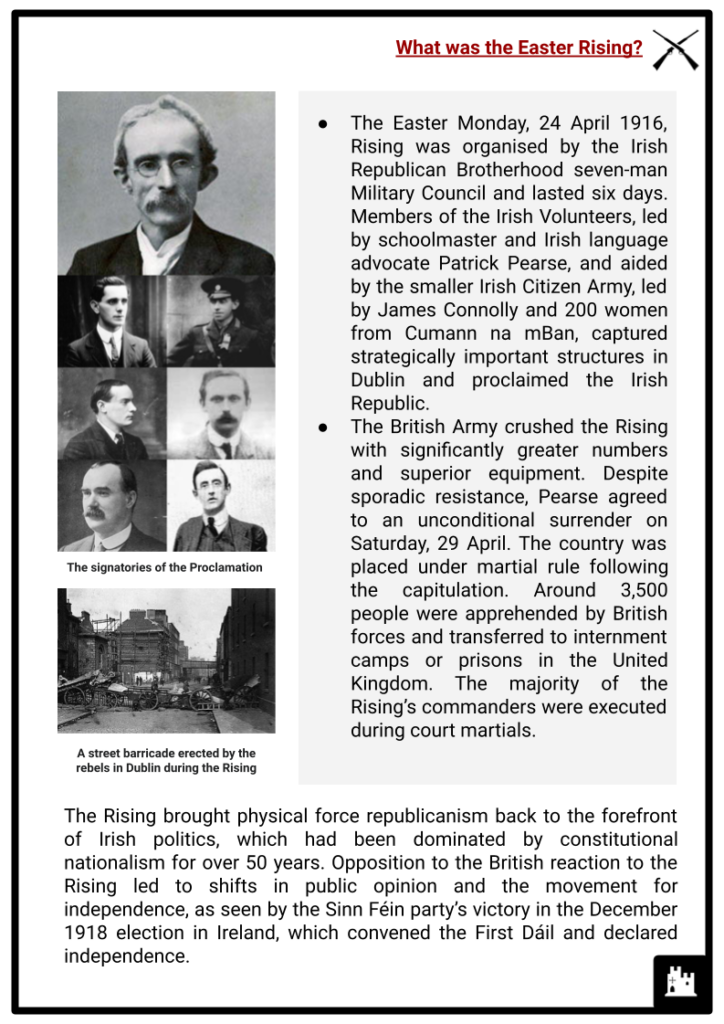

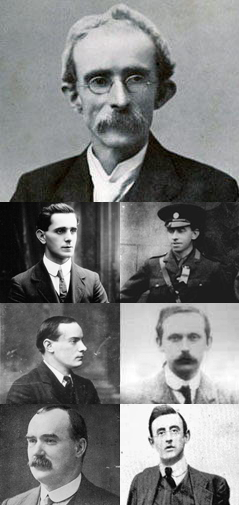

The signatories of the Proclamation - The Rising brought physical force republicanism back to the forefront of Irish politics, which has been dominated by constitutional nationalism for over 50 years. Opposition to the British reaction to the Rising led to shifts in public opinion and the movement for independence, as seen by the Sinn Féin party’s victory in the December 1918 election in Ireland, which convened the First Dáil and declared independence.

- In total, 260 civilians were slain, 143 British military and police personnel were killed, as well as 82 Irish insurgents, including 16 rebels hanged for their involvement in the Rising. Over 2,600 people were injured. Many people were killed or injured by British artillery fire or were mistaken for insurgents. Others were caught in the crossfire between the British and the insurgents. The bombardment and subsequent flames destroyed areas of central Dublin.

- Numerous Irish republicans criticised the union and the persistent lack of proper political involvement, as well as the British government’s management of Ireland and the Irish people, notably the Great Irish Famine, from the beginning. The opposition took several forms, including constitutional, social and revolutionary.

- The Irish Home Rule movement advocated for Irish self-government inside the United Kingdom. The Irish Parliamentary Party, led by Charles Stewart Parnell, was successful in getting the First Home Rule Bill tabled in the British parliament in 1886, but it was rejected. The House of Commons approved the Second Home Rule Bill of 1893, but the House of Lords rejected it.

- In 1912, British Liberal Prime Minister HH Asquith proposed the Third Home Rule Bill. Irish Unionists, the majority of whom were Protestants, were opposed because they did not want to be controlled by a Catholic-dominated Irish government. In January 1913, they founded the Ulster Volunteers, led by Sir Edward Carson and James Craig. In reaction, Irish nationalists founded the Irish Volunteers, a rival paramilitary force, in November 1913.

- The Irish Republican Brotherhood was a driving force behind the Irish Volunteers and tried to dominate them. Its leader was Eoin MacNeill. The proclaimed purpose of the Irish Volunteers was ‘to protect and maintain the rights and freedoms common to all the people of Ireland’. It welcomed ‘all able-bodied Irishmen without discrimination of faith, politics, or social group’. As a result of the Dublin lock-out that year, trade unionists organised another violent force, the Irish Citizen Army. British Army officers vowed to quit if they were forced to take action against the UVF.

Did you know?

The Dublin lock-out was a massive industrial conflict that occurred from 26 January 1913 until 19 January 1914. Poor working conditions, a lack of employees’ rights, and an inability to unionise were the causes of the strike. It was the most serious industrial conflict in Irish history.

- Planning the Rising

- The IRB’s Supreme Council convened on 5 September 1914, just over a month after the British government declared war on Germany. They determined at this conference to conduct an insurrection before the war finished in order to win German assistance. The Volunteers’ strategy included two components: first, preventing British access to the city centre from major British army bases and maintaining a communication line between Dublin and the countryside in order to have a line of escape if guerrilla warfare became necessary.

- Clarke and Mac Diarmada organised a Military Committee or Military Council inside the IRB in May 1915, consisting of Pearse, Plunkett and Ceannt, to devise preparations for a rising army.

- Shortly after the onset of World War I, Roger Casement and Clan na Gael chieftain John Devoy met with Johann Heinrich von Bernstorff, the German ambassador to the United States, to discuss German support for an insurrection. Casement travelled to Germany to begin talks with the German government and military. In November 1914, he got the Germans to declare their support for Irish independence. Casement also sought to form an Irish Brigade out of Irish POWs that would be equipped and dispatched to Ireland to join the insurrection.

- The Irish Citizen Army leader James Connolly was unaware of the IRB’s plans, and threatened to start a rebellion on his own if other parties failed to act. The IRB leaders convinced Connolly to join forces with them, and agreed to launch a rising together at Easter.

Learn More

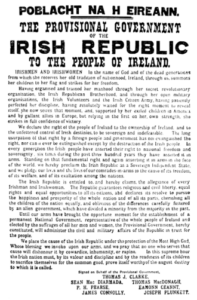

The 1916 Declaration, or the Easter Proclamation, was a manifesto published during the Easter Rising by the Irish Volunteers and the Irish National Army. The Irish Republican Brotherhood’s Military Council declared Ireland’s independence from the United Kingdom in it. The declaration was based on Robert Emmet’s similar independence declarations given during the 1803 revolt.

- Build-up to Easter Week

- Pearse gave orders to the Irish Volunteers on 9 April 1916 for three days of ‘parades and exercises’ commencing on Easter Sunday. The German Navy sent the SS Libau, disguised as the Norwegian ship Aud, to County Kerry. It was stocked with 20,000 weapons, one million rounds of ammunition, and explosives. Captain Casement, the captain of the Aud, was apprehended immediately after landing at Banna Strand. Through radio conversations between Germany and its consulate in the United States, British Naval Intelligence was made aware of the shipment and Casement’s return.

- Captain Casement was apprehended immediately after arriving at Banna Strand. MacNeill’s counter-order, cancelling all Volunteers activity for Sunday, postponed the Easter Rising by one day. When word of the Aud’s capture and Casement’s incarceration reached Dublin, Nathan met with Lord Wimborne, the Lord Lieutenant. The Military Council convened in Liberty Hall to debate what to do in the aftermath of MacNeill’s countermanding order. They determined that the Easter Monday Rising would take place, and that the Irish Volunteers and Irish Citizen Army would function as the ‘Army of the Irish Republic’.

The Rising in Dublin

- Easter Monday

- Around 1,200 Irish Volunteers and Irish Citizen Army troops gathered at various locations across central Dublin. Others dressed in regular clothes with a yellow Irish Volunteers armband, military headgear and bandoliers, while others dressed in Irish Volunteers and Citizen Army uniforms. They were mostly armed with rifles (especially 1871 Mausers), but also shotguns, revolvers and semi-automatic pistols. Rebels attempted to sabotage transportation and communication by erecting roadblocks, seizing bridges and cutting phone and telegraph lines. One group of Volunteers and Fianna Éireann members took over Phoenix Park’s Magazine Fort and disarmed the troops.

- The Castle, unknowing to the rebels, was poorly fortified and might have been simply controlled. Instead, the rebels began an assault on the Castle from City Hall. The British forces were entirely caught by surprise by the Rising, and their response on the first day was mainly unorganised; they were greeted by fire and casualties. Two squadrons of British cavalry were ordered to examine what was going on, as there were rebel soldiers in the GPO and the Four Courts. Margaret Keogh, a uniformed nurse, was slain at the Union by British soldiers. She is claimed to have been the first civilian killed during the Rising.

- Three disarmed Dublin Metropolitan Police officers were slain on the first day of the Rising, and their commissioner ordered them off the streets. A wave of looting occurred in the city centre, in part as a result of the police retreat, notably along O’Connell Street (still officially called Sackville Street at the time).

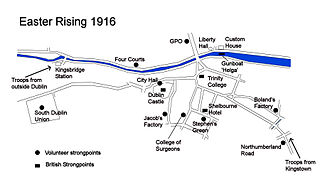

Positions of rebel and British forces in central Dublin

- Tuesday and Wednesday

- Brigadier-General William Lowe, the British commander in Dublin, came from the Curragh Camp on 25 April with just 1,269 soldiers. Initially, British soldiers concentrated their efforts on securing the approaches to Dublin Castle and isolating the rebel headquarters. The rebel squad that assaulted Dublin Castle on Tuesday morning was driven from City Hall. On Tuesday afternoon, fighting erupted around the northern fringe of the city centre as British forces departed Amiens Street train station to repair damaged rails. Rebels in the GPO, Four Courts, Jacob’s Factory, and Boland’s Mill saw minimal combat because British soldiers surrounded and shelled them rather than attacking them directly.

- Some rebel leaders, especially James Connolly, did not think the British would shell the British Empire’s ‘second city’. Their weaponry was supplied by field guns stationed on the city’s northside at Phibsborough and Trinity College, as well as the patrol cruiser Helga. During the Battle of the Grand Canal on 26 April 1916, rebels in Heuston were the first insurgent position to surrender. British forces marched on the structure, backed up by snipers and machine-gun fire, but the Volunteers resisted valiantly. Over 1,000 Sherwood Foresters were caught in the crossfire as they attempted to cross the canal at Mount Street Bridge. For only four dead volunteers, the combat there resulted in two-thirds of the British casualties for the whole week.

- Thursday to Saturday

- The South Dublin Union, which housed St James’s Hospital, saw some of the most severe combat of the Rising. British forces were also heavily wounded in failed frontal attacks on Marrowbone Lane Distillery and North King Street. By the end of the week, the British had seized control of certain Union buildings, while others remained in rebel hands. The insurgents had built strongholds in the region, taking up a number of small houses and barricading roadways.

- Surrender

- The O’Rahilly were killed in a sortie from the GPO on 29 April 1916. The headquarters of the Provisional Government (PPG) had been taken over by Pearse after Connolly’s death, but he issued an order for all companies to surrender. Sporadic fighting continued until Sunday, when word of the surrender was got to the other rebel garrisons. Pearse surrendered unconditionally to Brigadier-General Lowe.

The Rising outside Dublin

- On Easter Sunday, Irish Volunteer battalions mobilised in many locations outside of Dublin, but the majority of them returned home without fighting. Around 1,200 Volunteers led by Tomás Mac Curtain assembled in Cork on Tuesday, but dispersed on Wednesday after receiving nine contradicting instructions from the Volunteers headquarters in Dublin. Some Volunteers participated in a confrontation with British soldiers at their Sheares Street headquarters, and MacCurtain consented to surrender his men’s guns to the British.

- FingalAround 60 Volunteers gathered in Fingal (north County Dublin) and stormed the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) barracks, compelling them to surrender. To prevent troop trains from reaching Dublin, they also sabotaged railway lines and cut telegraph cables. Outside of Dublin, the only large-scale fight took place in Ashbourne, County Meath, when the RIC surrendered and were disarmed. On 24 April, Volunteers shot dead an RIC man in the village of Castlebellingham in County Louth, and 15 RIC personnel were taken prisoner.

- EnniscorthyOn Thursday 27 April, 100–200 Volunteers commanded by Robert Brennan, Séamus Doyle and Seán Etchingham took over the town of Enniscorthy in County Wexford until Sunday. They raised the tricolour over the Athenaeum building, which had become their headquarters, and paraded through the streets in uniform. They also took over Vinegar Hill, where the United Irishmen made their last stand during the 1798 insurrection. The people overwhelmingly backed the insurgents, and many local men offered to join them. Up to 1,000 rebels had been mobilised by Saturday, and a detachment had been deployed to take the adjacent community of Ferns.

- GalwayThe majority of the fighting took place in County Galway, as rebels attempted but failed to raid RIC barracks and seized officials. The western Rising had already dissolved by the time British forces arrived. Following the Rising, several people returned home and were detained, while others went ‘on the run’.

- Limerick and Clare

- In County Limerick, 300 Irish Volunteers gathered at Glenquin Castle near Killeedy, but no military action was taken.

- On Easter Monday, Michael Brennan marched to the River Shannon with 100 Volunteers (from Meelick, Oatfield and Cratloe) awaiting orders from the Rising leaders in Dublin, as well as armament from the anticipated Clerestory shipment. Neither of them arrived, and no action was taken.

- During the Troubles in Northern Ireland, at least 2,200 people were murdered and over 2,600 were injured. The British Army was responsible for the majority of the losses, both the dead and injured. This was due to artillery, incendiary rounds, and heavy machine guns used in urban areas. Many more bystanders were slain when they were caught in the crossfire. There were other incidents of British troops murdering unarmed villagers in retaliation or anger. Following the war, the great majority of Irish casualties were interred in Glasnevin Cemetery. In May 1916, British families flocked to Dublin Castle to recover the remains of British soldiers, and funerals were held.

Aftermath

- British atrocities

- Following the Easter Rising of 1916, accusations of atrocities committed by British troops in Dublin provoked resentment among the Irish people. Captain John Bowen-Colthurst was convicted of murder but declared insane and sent to Broadmoor for 20 months. Major Sir Francis Vane called his superiors in Dublin Castle after learning of the killings, but no action was taken. A public inquiry was launched as a result of public outcry, but it reached the same conclusions. Colonel Henry Taylor’s British soldiers of the South Staffordshire Regiment murdered 15 male civilians in April 1916, accusing them of being rebels.

- After plundering the captives, the troops shot or bayoneted them and buried some of them in cellars or backyards. According to the findings of the inquest, troops murdered ‘unarmed and unoffending’ people. A military court of enquiry determined that no particular troops could be held accountable.

- Arrests and executions

- A total of 3,430 men and 79 women were apprehended, with 425 facing looting charges. The majority of the 187 people who were tried were kept in Richmond Barracks. General Maxwell chose to convene the court martials in secret and without a defence, which Crown legal officers later determined was illegal. According to Maxwell, only the ‘ringleaders’ and those proven guilty of ‘coldblooded murder’ would be executed. As the executions continued, the Irish people grew increasingly antagonistic towards the British and more sympathetic towards the insurgents.

- The majority of those detained were later freed. However, under Regulation 14B of the Defence of the Realm Act 1914, 1,836 men were incarcerated at internment camps and prisons throughout England and Wales. Internment camps like Frongoch became ‘Universities of Revolution’ where future leaders like Michael Collins, Terence McSwiney and JJ O’Connell began making plans for independence.

- Reaction of the Dublin public

- The start of the Rising first perplexed many Dubliners. Some residents of the city were extremely hostile to the Volunteers. The majority of the resistance came from people who had relatives in the British Army. Following the surrender, the Volunteers were shouted at, showered with garbage, and labelled ‘murderers’. Following the Easter Rising of 1916, a major segment of Irish nationalist thought shifted in favour of the Easter 1916 rebels.

- Many people in impoverished districts of Dublin sympathised with the rebels but were hesitant to voice their feelings for fear of being killed. The British response to the Rising, as well as the ensuing British military control of the city, altered many people’s political perspectives.

- Inquiry

- A Royal Commission was formed to investigate the reasons for the Rising. Sir Matthew Nathan, Augustine Birrell, Lord Wimborne, Sir Neville Chamberlain (Inspector-General of the Royal Irish Constabulary), General Lovick Friend, Major Ivor Price of Military Intelligence and others testified before the commission. The report, released on 26 June, was scathing of the Dublin government, stating that ‘Ireland had been run for several years on the assumption that it was safer and more convenient to keep the law in abeyance’.

- Rise of Sinn Féin

- On 19 April 1917, Count Plunkett organised a conference, which resulted in the establishment of Sinn Féin, which was confirmed at the Ard Fheis on 25 October 1917. The Conscription Crisis of 1918 heightened popular support for Sinn Féin ahead of the general elections to British Parliament on 14 December 1918, which Sinn Féin won by a landslide. On 21 January 1919, members of parliament met in Dublin to create the Dáil Éireann and approve the Declaration of Independence.

- Some of the Rising survivors went on to become leaders of the newly independent Irish state. Every year on Easter Sunday, a commemoration military parade was staged. Éamon de Valera presented a monument of the mythological Irish warrior Chulainn in 1935. In 1966, Ireland minted its first commemorative coin to commemorate the Easter Rising. Ireland also minted a €2 coin in 2016 to mark the centennial of the Rising.

- With murals and yearly parades, Irish republicans continue to honour the Rising and its leaders. During the 1990s, the government’s attitude towards the Rising improved. In 1996, the Garden of Remembrance had an 80th anniversary observance. In 2006, a military parade was held in Dublin to commemorate the 90th anniversary. The documentary The Enemy Files, presented by former British Secretary of State for Defence Michael Portillo, was screened in 2016.

Image Sources

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5b/The_shell_of_the_G.P.O._on_Sackville_Street_after_the_Easter_Rising_%286937669789%29.jpg/330px-The_shell_of_the_G.P.O._on_Sackville_Street_after_the_Easter_Rising_%286937669789%29.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f7/Signatories_of_the_Proclamation_of_the_Republic.png

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Easter_Proclamation_of_1916.png/330px-Easter_Proclamation_of_1916.png

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e9/Easter_rising_1916.jpg/330px-Easter_rising_1916.jpg