Download Emily Hobhouse Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Emily Hobhouse to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Early life of Emily Hobhouse

- Second Boer War

- Conditions of the concentration camps in the Boer War

- Fawcett Commission

- Late life and death of Emily Hobhouse

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about Emily Hobhouse!

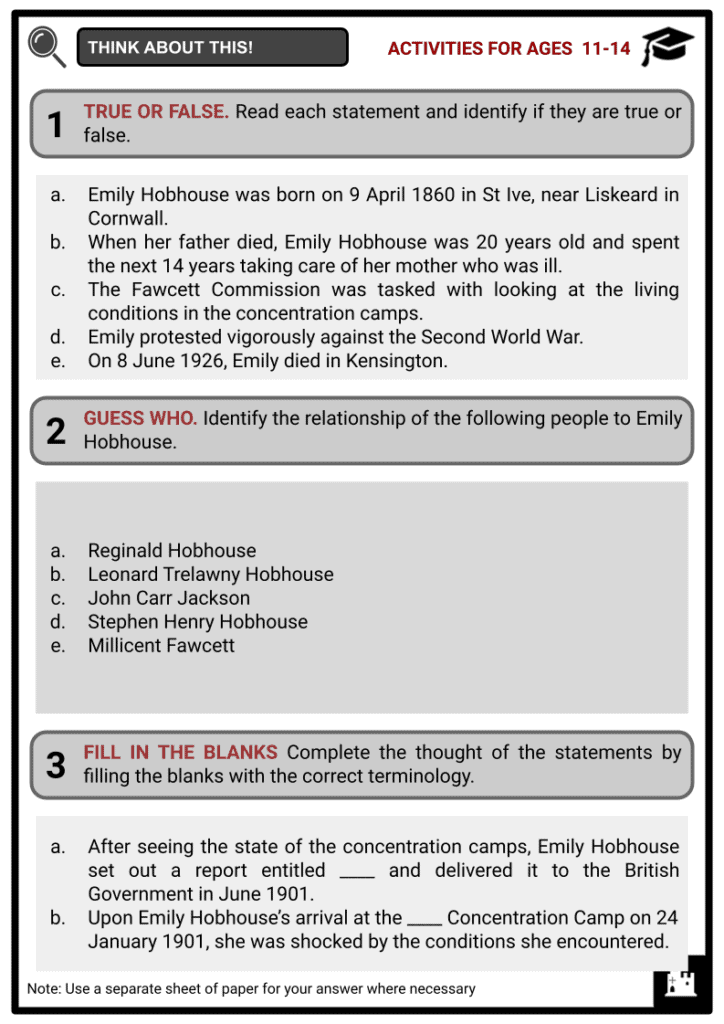

Emily Hobhouse was a British anti-war activist, pacifist, social worker, and welfare campaigner well-known for her humanitarian works, specifically in South Africa during the Second Boer War.

Emily’s arrival at the Bloemfontein Concentration Camp on 24 January 1901 encouraged her to write a report that she delivered to the British government in June of the same year. Her report was key to the setting up of the Fawcett Commission that aimed to look at the living conditions in the concentration camps.

Early life of Emily Hobhouse

- Emily Hobhouse was born on 9 April 1860 in St Ive, near Liskeard in Cornwall. She was the daughter of Reginald and Coraline Hobhouse. Her father, Reginald, was an Anglican rector and the first Archdeacon of Bodmin. Emily was also the sister of the peace activist and proponent of social liberalism, Leonard Trelawny Hobhouse. A major influence on her as she was growing up was her second cousin, Stephen Henry Hobhouse.

- When her mother died, Emily was 20 years old and spent the next 14 years taking care of her father, who was ill. In 1895, after her father died, she then went to Minnesota to perform welfare work amongst Cornish mine workers. It was here that she became engaged to John Carr Jackson. However, the engagement broke off soon after. In 1898, Emily returned to England.

Second Boer War

- In October 1899, when the Second Boer War broke out in South Africa, Leonard Courtney invited Emily to become the secretary of the women’s branch of the South African Conciliation Committee. On 7 December 1900, after founding the Distress Fund of South African Women and Children, Emily sailed to Cape Colony to supervise its distribution.

- Upon Emily’s arrival at the Bloemfontein Concentration Camp on 24 January 1901, she was shocked by the conditions she encountered. She persuaded the authorities to visit and deliver aid to the 45 camps found. She set out a report entitled ‘Report of a Visit to the Camps of Women and Children in the Cape and Orange River Colonies’ and delivered it to the British Government in June 1901. As a result of her report, a team of official investigators headed by Millicent Fawcett was sent to inspect the camps.

Conditions of the Camps

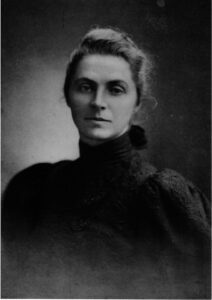

Mortality rates in the concentration camps were high, reaching a total of 26,370, of which 24,000 were children. Some 50 children a day died in the camps due to overcrowding in unhygienic conditions, lack of resources, and a cruel system.

- The tents in the camps were overcrowded, and the extremely hot weather conditions weren’t helpful at all. The heat outside the tents made the inside suffocating, not to mention that the tents were occupied by more than six people, all crammed in together.

- Emily recalls a certain Mrs M who had five children and a little Kaffir servant girl inside the tent with her. Whenever it rained, the water came through the single canvas of the tents and soaked everything inside. So they spent mornings waking up to dry out their things in the sun. The harsh conditions in the tents made many of its occupants sick, and a lot also died.

- Due to lack of resources, the camps were also very unhygienic. Soap, for one, was treated as a luxury as it was only given occasionally and in minimal quantities. So there was not enough for clothes and personal washing.

- Aside from typhoid, Emily was most distressed about the undernourished sick children at the camp who were suffering from measles, dysentery, bronchitis, and pneumonia. She recalled the plight of Lizzie van Zyl who died at Bloemfontein after being treated harshly and placed on the lowest rations in the camp.

- After quite some struggle, Emily succeeded in listing and delivering the necessities such as soap, straw, more kettles, and more tents. She was also able to distribute clothes and mattresses for pregnant women in the camps who had nowhere to sleep but on the ground. After her visit to Bloemfontein, she also extended help to Norvalspont, Aliwal North, Springfontein, Kimberley, and Orange River concentration camps.

Fawcett Commission

- After her aid in the camps, Emily returned to England, where she was met with criticism from the British government and media. Eventually, she succeeded in obtaining more funding for the Boer civilians in the camps. The British government also agreed to set up the Fawcett Commission, under the leadership of Millicent Fawcett, to investigate the claims in Emily’s report.

- The Commission was tasked with looking at the living conditions in the concentration camps. Like Emily, Fawcett suggested reforms such as an increase in food rations, the use of kettles for drinking water, access to washing facilities, and the isolation of sick individuals.

Later Life and Death

- Throughout the next years of Emily’s life, she felt that she had never received justice for her work. In 1902, she went to Lake Annecy in the French Alps, where she wrote the book The Brunt of the War and Where it Fell to retell what she had seen in the Boer War in South Africa.

-

The Brunt of the War and Where it Fell After the war, she returned to South Africa, where she assisted in healing the wounds inflicted during the war and supported efforts that aimed at rehabilitation. She also set up a home industries scheme to teach young women spinning, weaving, and lace-making so that they could have an occupation while they stayed at home.

- In 1913, she travelled to South Africa again for the inauguration of the National Women’s Monument in Bloemfontein. Due to her failing health at that time, her speech for goodwill and reconciliation between all races was read for her and was able to receive great acclaim.

- Emily also protested vigorously against World War I. In January 1915, she organised the writing, signing, and publishing of the ‘Open Christmas Letter’ that was written in acknowledgment of the horrors of modern wars. This exchange of letters between women from different nations at war, ignited by the common goal of the suffrage of women, was able to promote peace and help them to become united. Through Emily’s offices, many women and children were fed daily in central Europe after the war.

- Due to her humanitarian work in South Africa, she became an honorary citizen of the country. Moreover, a sum of £2,300 was collected from the Afrikaner nation to be given to Emily, which she used to purchase a house in St Ives, Cornwall. The house now forms a part of the Porthminster Hotel, where a commemorative plaque of Emily was placed as a tribute to her humanitarianism and heroism during the Boer War. On 8 June 1926, Emily died in Kensington. Her cremated remains were spread at the National Women’s Monument in Bloemfontein.