Meiji Japan Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Meiji Japan to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Tokugawa Period

- Meiji Restoration

- Social and Economic Changes

- After the Meiji Era

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about Meiji Japan!

Meiji is a Japanese period that began on 23 October 1868 and ended on 30 July 1912. The Meiji era encompasses the first half of the Empire of Japan. The most notable event was the Japanese people's transformation from an isolated feudal state-society to an industrialised nation-state.

Since the Japanese adopted revolutionary new ideas, many aspects of Japanese society have changed dramatically, including the social structure, politics, economy, military, and foreign relations. The period was named after Emperor Meiji, the ruler of Japan at the time such events occurred.

Tokugawa Period

- Japan's Tokugawa period lasted from 1603 to 1867. It was the end of the traditional Japanese government, culture, and society. The period was ruled by Tokugawa Ieyasu and was commonly referred to as a dynasty of shoguns or military dictators who ruled Japan for over 250 years of peace. Japanese society was also isolated from Western countries, avoiding outside influences, particularly Christianity.

Tokugawa Ieyasu - Neo-Confucian theory dominated the Tokugawa period, which recognised samurai, artisans, farmers, and merchants as the only social classes. During that time, it was illegal to move from one of the aforementioned social classes to another.

- However, because the peace was preserved, the samurai or warriors either became bureaucrats or entered the trade. But they were frustrated because they were still expected to maintain their warrior pride and readiness for military attacks despite the situation.

- A large portion of Japan's peasant population was limited to agricultural activities.

- During this time, the country experienced economic growth. Rice, sesame oil, indigo, sugar cane, mulberry, tobacco, and cotton were among the crops grown by peasants. With such a diverse range of agricultural products, Japan's commerce and manufacturing industries expanded, resulting in increased merchant wealth and the growth of Japanese cities.

- A thriving urban culture evolved, concentrated in Kyoto, Osaka, and Edo (Tokyo), catering to merchants, samurai, and townspeople rather than the traditional patrons and daimyo. The Genroku period (1688-1704) saw the emergence of Kabuki theatre and Bunraku puppet theatre, literature, and woodblock printing in particular.

Meiji Restoration

- The Tokugawa shogunate became weak as a result of the continued peace. Two prominent clans saw this as a chance to join forces and gain power in the name of "imperial restoration," which became known as the Meiji Restoration. The Meiji Restoration in Japan eliminated feudalism and gave birth to contemporary Japanese culture.

- Emperor Meiji was only fifteen years old when he ascended to the throne in 1867, therefore, he lacked governing authority. As a result, the new administration was ruled by a cabinet of advisers.

- The new cabinet set out to strengthen and unite Japan by enacting a series of reforms. Their main focus, however, was Japan's modernisation, which they saw as the key to Japan regaining its sovereignty.

- The majority of reforms implemented were heavily influenced by the West, though Japan's cultural and historical roots could still be seen.

- The abolition of the traditional social hierarchy based on inherited status was one of the most notable reforms. A Japanese in any one of the social classes could now freely choose to live as a farmer, warrior, merchant, or artisan.

- The changes in the Meiji government were made possible by the Charter Oath, which was published in 1868. The document contains an outline of the new government's goals and policies. This also laid the groundwork for the reforms that would be implemented in the coming decades. The oath was considered to have been written by Yuri Kimimasa.

The Charter Oath of the Meiji Restoration (1868)

“By this oath we set up as our aim the establishment of the national on a broad basis and the framing of a constitution and laws.

-

- Deliberative assemblies shall be widely established and all matters decided by public discussion.

-

- All classes, high and low, shall unite in vigorously carrying out the administration of affairs of state.

-

- The common people, no less than the civil and military officials, shall each be allowed to pursue his own calling so that there may be no discontent.

-

- Evil customs of the past shall be broken off and everything based upon the just laws of Nature.

-

- Knowledge shall be sought throughout the world so as to strengthen the foundations of imperial rule.”

- The goal was to progress towards democracy, and most early reformers believed that such reforms, as well as diplomatic equality and military strength, were required to achieve that goal.

- Emperor Meiji, living by the era's motto "Enrich the Country and Strengthen the Military," supported the efforts in both practise and appearance. He made his appearance reflect the Western-style, such as his military clothing, hairstyle, and the kaiser moustache he grew.

- The Meiji government officials also benefited from the elite band of oligarchs. Their primary goals were to strengthen the government by implementing land tax reforms and military conscription.

- Emperor Meiji and his oligarchs spent the next four decades making education compulsory and investing in various markets.

- Western-style weapons, uniforms, and even military education models were adopted. While some Japanese accepted the changes unconsciously, others actively opposed them. The reforms were heavily influenced by Japanese officials' visits to the United States and Europe.

- Iwakura Tomomi led a diplomatic mission to the United States and Europe with a delegation of nearly fifty government officials.

- Iwakura believed that a high level of modernisation would ensure Japanese sovereignty.

- However, Iwakura and his delegates were unable to complete the mission. Despite this, they gathered many ideas for various reforms from Western culture and institutions.

- A statesman, Ito Hirobumi, was among the delegation. During the mission, he documented what they saw and experienced, including currency systems, education, and technology. The role of constitutions was also examined.

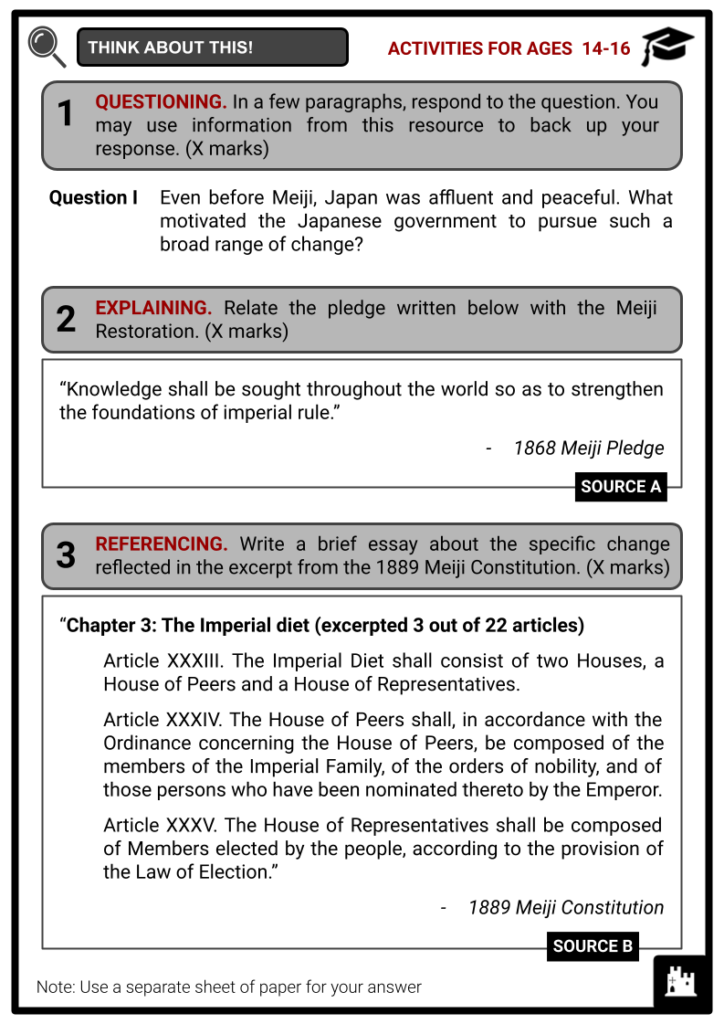

- The Meiji Constitution was then draughted in 1881 and promulgated eight years later. The constitution defines the Emperor's and all Japanese citizens' roles and responsibilities.

- The imperial system, however, was preserved by the authors of the Meiji Constitution to connect the past and the present.

Social and Economic Changes

- Because of the abolition of feudalism, people were free to choose their occupations, creating a new environment of political and financial security. The government was in a position to invest in new industries and technologies.

- In Japan, government investments built railways and shipping lines. Telegraph and telephone networks also appeared. Many other products were produced, but the high cost of the investments put a strain on the government's finances. The newly constructed industries were sold to private investors in 1880.

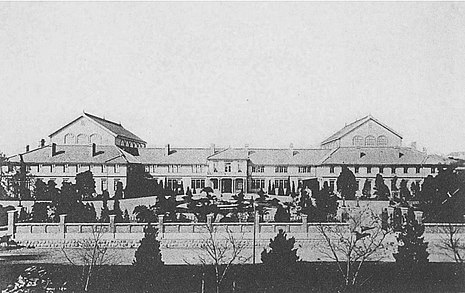

- The newly established national education system established an elected legislature known as the Diet. This was done to achieve national growth, Western respect, and support for the modern state.

First Diet Hall Built from 1890-1891 - By the end of the Meiji period, almost everyone had completed at least six years of free public schooling. The government ensured that "moral training" was included in the curriculum of schools, teaching children about their responsibilities to the emperor, the country, and their families.

- The emperor "gave" the people the 1889 constitution, and only he (or his advisers) could amend it.

- Beginning in 1890, a parliament was elected, although only the wealthiest of the population could vote.

- This was amended in 1925 to allow all men (but not yet women) to vote.

- To gain Western legitimacy and persuade them to reverse the unequal treaties that the Japanese were forced to sign in the 1850s, Japan overhauled its whole legal system, adopting a new criminal and civil code fashioned after those of France and Germany.

- In 1894, the Western powers agreed to modify the treaties, recognising Japan as an equal in concept but not an international power.

After the Meiji Era

- The Meiji reforms brought about changes not only within Japan but also in the country's international relations. Japan was successful in retaining sovereignty, allowing them to oppose Western invaders while still expanding their colonising might. Japanese residents seeking greater social liberties embraced the post-Meiji period. This ushered in Japanese culture and political system based on democracy.

Emperor Taisho - The Japanese people became increasingly prosperous. Traditional values were weakened by industrialisation, which emphasised efficiency, independence, materialism, and individualism.

- During these years, the Japanese people began to seek universal suffrage, which they obtained in 1925.

- Between 1918 and 1931, political parties grew in power, becoming powerful enough to pick their prime ministers.

- Following World War I, Japan experienced a severe economic downturn.

- The Taishô period's bright, hopeful aura gradually faded. Corruption plagued the political party government. As a result, the government and military got stronger, while the parliament weakened.

- The sophisticated industrial sector was increasingly dominated by a few large corporations known as zaibatsu. Furthermore, trade tensions and growing worldwide opposition to Japan's operations in China strained Japan's international relations.

- Japan's success in competing with European powers in East Asia reinforced the notion that Japan could, and should, further expand its influence on the Asian mainland through military force.

- Japan's hunger for natural resources, as well as the West's repeated rejections of Japan's ambitions to expand its authority in Asia, cleared the path for militarists to rise to power.

- Insecurity in international relations enabled a right-wing militaristic movement to seize control of foreign and then domestic affairs.

- With the military heavily influencing the government, Japan launched an aggressive military campaign throughout Asia before bombing Pearl Harbour in 1941.

Image Sources

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/48/Promulgation_of_The_New_Japanese_Constitution_%281889%29.jpg/330px-Promulgation_of_The_New_Japanese_Constitution_%281889%29.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/11/Tokugawa_Ieyasu2.JPG/330px-Tokugawa_Ieyasu2.JPG

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1e/The_First_Japnese_Diet_Hall_1890-91.jpg/465px-The_First_Japnese_Diet_Hall_1890-91.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/52/Emperor_Taisho_of_Japan.jpg/330px-Emperor_Taisho_of_Japan.jpg