Download The Freikorps Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach The Freikorps to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Table of Contents

Add a header to begin generating the table of contents

Summary

- Origin and history of the Freikorps

- The Freikorps during the Weimar Republic

- The Freikorps in the Baltic region

- Legacy left by the Freikorps

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about The Freikorps!

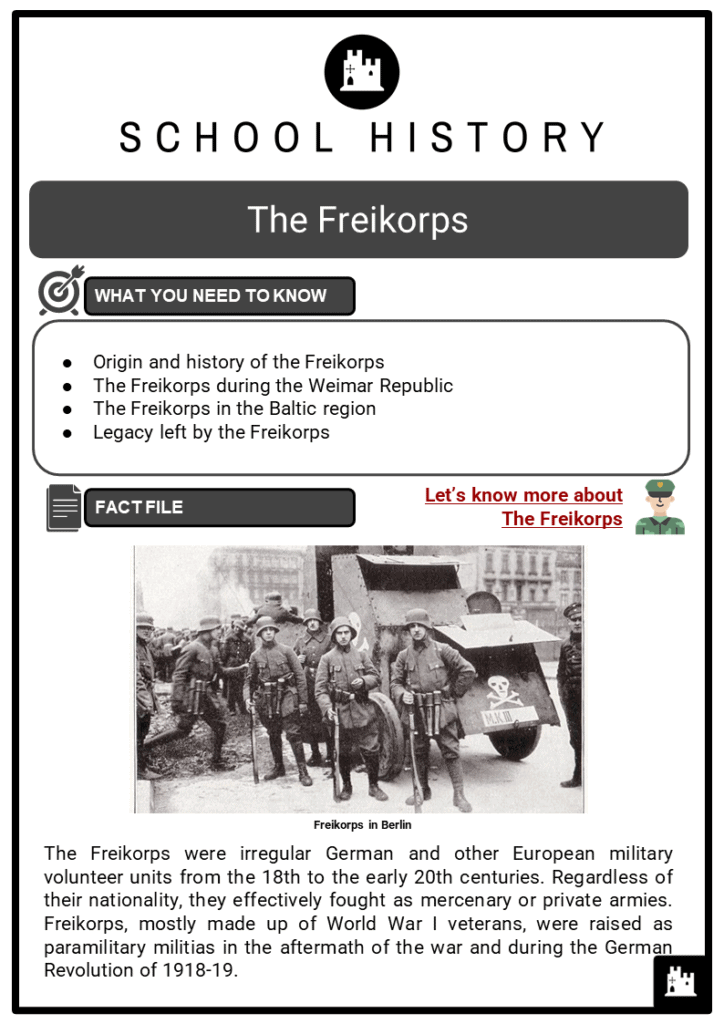

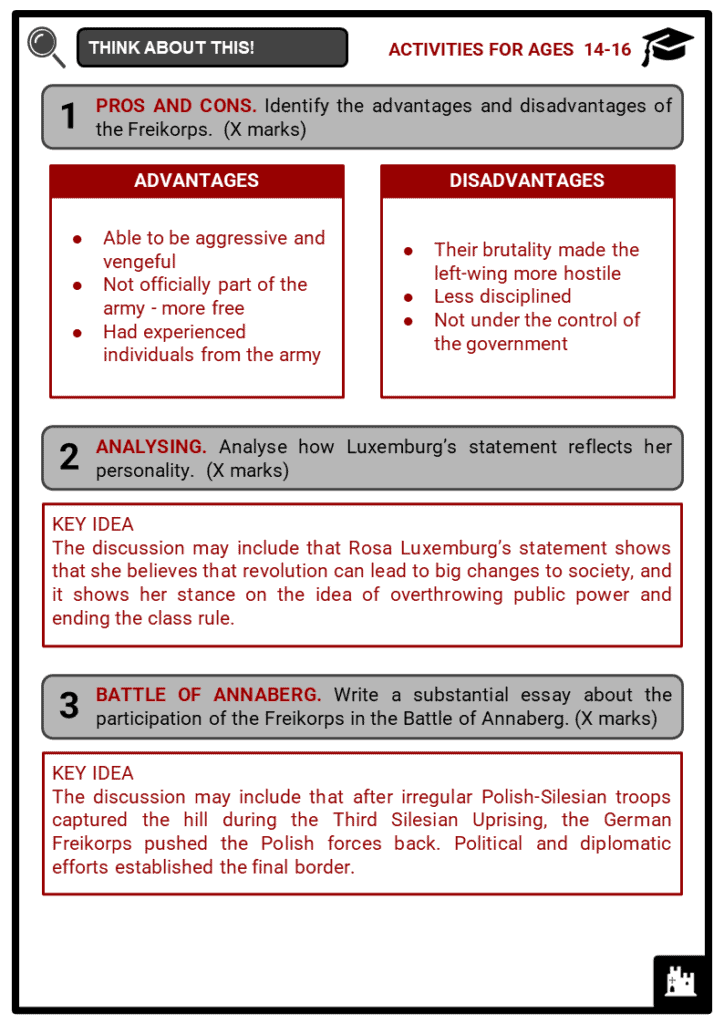

- The Freikorps were irregular German and other European military volunteer units from the 18th to the early 20th centuries. Regardless of their nationality, they effectively fought as mercenary or private armies. Freikorps, mostly made up of World War I veterans, were raised as paramilitary militias in the aftermath of the war and during the German Revolution of 1918-19.

- They were ostensibly recruited to fight on the government’s behalf against German communists supported by the RSFSR who were attempting to overthrow the Weimar Republic. Many Freikorps, on the other hand, loathed the Republic and participated in assassinations of its supporters.

- Initially, the term ‘Freikorps’ (which in German signifies ‘free bodies’) designated armies made up of volunteers and trained in small German states between the 17th and 18th centuries. Originally it was a body of irregular soldiers, however after the First World War it also integrated German veterans of the Reichsheer.

- During the interwar period of the 20th century, this organisation was known for its strong nationalist ideologies and its aversion to communism. During the Weimar Republic, the Freikorps collaborated with the government in the repression of the workers’ movement and other leftist organisations, taking part in events such as the Spartacist Uprising or the Ruhr Uprising, as well as participating in the failed Kapp coup d’état against the young republic.

Origin And History

- The first Freikorps were recruited in 1762 by Frederick II the Great of Prussia during the Seven Years’ War, as voluntary fighters subject to military discipline. The free infantry, which consisted of numerous military branches (such as infantry, hussars, dragoons and jäger) and were deployed in combination, should be distinguished from the Freikorps developed for the latter years of the war, which acted independently and disturbed the enemy with surprise attacks.

- During the war, eight such volunteer corps were set up:

- Trümbach’s Freikorps (Voluntaires de Prusse) (FI)

- Kleist’s Freikorps (FII)

- Glasenapp’s Free Dragoons (F III)

- Schony’s Freikorps (F IV)

- Gschray’s Freikorps (F V)

- Bauer’s Free Hussars (F VI)

- Légion Britannique (FV - of the Electorate of Hanover)

- Volontaires Auxiliaires (F VI)

- They frequently used to keep Maria Theresa’s Pandurs at range. Light troops were considered vital for outpost, reinforcement and reconnaissance roles during the age of linear tactics.

- Other Freikorps appeared in Germany during the Napoleonic Wars and fought against the French soldiers. This group of Freikorps was formed by irregular troops which often comprised students or young aristocrats without much war experience.

- The Freikorps that participated during the Napoleonic Wars were led by professional military leaders, such as the Prussian General Ludwig Adolf Wilhelm von Lützow, head of the so-called Lützowsches Freikorps of 1810-1814.

- Since the Freikorps were initially viewed with considerable distrust by the Prussian regular army, they initially worked as sentinels and were used for other minor duties. In fact, they were not considered particularly skilled for combat. However, the German nationalist romanticism of the early 19th century developed an idealised image of the Freikorps: it depicted them as combatants driven by a purely idealistic and patriotic impulse, fighting against a foreign invader, and acting beyond the duty of a professional soldier.

During The Weimar Republic

- As of the November Revolution of 1918, the term was used by the first fascists and ultranationalist paramilitary organisations that were formed throughout Germany. With the establishment of the Weimar Republic, the Freikorps were among the many active paramilitary groups. They held various ideologies and belonged to different parties (therefore, they were not unanimous in their thinking).

- The Freikorps were at times tolerated and encouraged by the authorities of the young republic, as an alternative to the communist and socialist trade union organisations that were also flourishing during the same period.

- Numerous German veterans of the First World War felt deeply disconnected and misunderstood in civil life after years of extremely violent struggle in the trenches; others lacked incentives to rejoin German society due to unemployment and the poor economic situation of the postwar period.

- The Freikorps encouraged young veterans of the German armed forces to join them: the veterans were mostly looking for stability and a military structure that could offer them social status.

- Other individuals joined the Freikorps because they were feeling frustrated with the unacceptable defeat of 1918.

- Part of the typical Freikorps ideology was a complete disdain for democracy and capitalism. Not only were they animated by hatred towards Marxism, but they also had deep feelings of anti-Semitism since they believed that the Jews and leftists were responsible for the German defeat.

- When the left-wing parties joined the Spartacist Revolt in January 1919 in Berlin, the Freikorps received the unspoken support of Gustav Noske, the German Minister of Defence, who used them to repress the Spartacist League with great violence.

- He also carried out the assassinations of Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg on 15 January 1919.

- That same year, the Freikorps supported the republican government in the crushing of the newly created Bavarian Soviet Republic, ruled by the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany.

- With the dissolution of the former imperial army and the limitation of the Reichswehr to 100,000 men under the Treaty of Versailles, the Freikorps participated in numerous violent clashes against the communist and socialist workers throughout Germany as a paramilitary group.

- However, other Freikorps preferred to remain ‘free’ paramilitaries without subordinating themselves to the government or carrying out orders from the government. They also carried out sporadic attacks of sabotage against the French troops during the occupation of the Ruhr, gaining great fame and popularity among the German masses despite the fact that such attacks actually caused little damage to the occupying authorities.

- The Freikorps were officially dissolved in 1920 by the Weimar Republic and war veterans were prevented from forming paramilitary groups. However, their former members took part in the Munich Putsch led by Adolf Hitler, a failed 1923 coup attempt.

- Members of the Freikorps also participated in the assassination of the German Minister of Foreign Affairs, the Jewish economist and industrialist Walter Rathenau, in June 1922.

- These Freikorps were gradually disarmed as the German economy was revitalised and as soon as the threat of inflation disappeared by the end of 1923.

- Shortly thereafter, the German Freikorps quickly disappeared as groups, but the more radical members continued to form small ultra-nationalist and far-right groups, making sporadic attacks against the republican authorities, and some of the younger members became part of the SA of the National Socialist Party.

In The Baltic Region

- Several Freikorps fought in the Baltic, Silesia and Prussia after the end of the First World War, sometimes with significant success against regular troops. However, in 1919, they were finally defeated in Silesia and Prussia by the troops of the newly rebuilt Poland.

- The Baltic Freikorps also played a significant role: the initial plan of these soldiers was that of protecting the Baltic Germans against the Russian Bolsheviks and against the nationalists of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. For this reason, these Freikorps formed an army under the leadership of the large German landowners in the region: they mostly relied on dissatisfied German soldiers after their demobilisation on the Eastern Front in November 1918.

- In the first part of 1919, the Freikorps’ initial plan soon transformed into the project of creating the Baltic States, which would be controlled by the German minority and would subjugate the Baltic peoples by taking advantage of the disorders generated by the Russian Civil War.

- The German landowners of the Baltic encouraged the Freikorps to undertake this mission by offering generous rewards to veterans.

- In fact, they thanked them for their help by giving them large farms with native labour.

- The promise of adventure and combat, the encouragement to defend the Germanic East against Slavic and Baltic peoples, and the offer to be splendidly awarded farms in the vast territories of Eastern Europe, attracted thousands of German veterans to the Baltic, who operated there since the beginning of 1919.

- Despite the valuable combat experience of the German Freikorps, the Berlin government could not openly support them since they were fighting outside the German borders.

- The Freikorps also faced the strong war and economic pressures of Great Britain (which was favourable to the total independence of the Baltic countries). Moreover, the Freikorps encountered opposition due to the fact that the Baltic Germans were a minority within the community and they did not have the right to impose their rule over the Estonian, Latvian and Lithuanian masses.

- During their struggle in the Baltic, the German Freikorps were accused by the Baltic nationalists of being mass murderers of civilians: they furiously destroyed and brutally abused non-German populations. In fact, the Freikorps’ indiscipline was very evident since the beginning of the fight: many of the components of the group were German soldiers and gangs with a love of adventure, pillage, alcohol and indiscriminate violence.

- As a consequence, the Freikorps’ indiscipline and lack of control greatly reduced their military effectiveness, and they began to suffer frequent defeats and losses during the 1920s. The disorganised German Freikorps were ultimately defeated by the Baltic nationalists in early 1921. The survivors repatriated and had to abandon their dream of achieving a great state colonised by Germans on the shores of the Baltic Sea.

Legacy

- Due to their extreme right ideology, many of its young members became future leaders of the Nazi party. These include Ernst Röhm, future head of the Sturmabteilung (SA), and Rudolf Höss, future commander of Auschwitz. Although the majority of the Freikorps veterans sympathised with Adolf Hitler (another war veteran) during the 1920s, many also reproached him for not having actively participated in the struggle against the communists and socialists between 1919 and 1920. Almost all Freikorps veterans maintained an ultra-nationalist, anti-communist, anti-Semitic and far-right ideology, along with a great disdain for democracy.

- Hans von Seeckt’s restructuring of the Reichswehr broke the Freikorps movement from an organisational standpoint. After 1923, the operation of the Freikorps changed dramatically, and they were reorganised as ‘political combat leagues’, with little military value. Due to a lack of firepower and legal protection, Freikorps units shifted their concentration to street brawls and dispersing socialist and communist gatherings.

- Many Freikorps members departed to become private individuals or to join other organisations such as the Stahlhelm Veterans Association or the National Socialists SA (Sturmabteilung or Storm Troopers).

- The Freikorps fighter became a plastic symbol of nationalism, anti-communism and militarised masculinity deployed by NSDAP to co-opt the lingering social and political support of the once powerful movement.

Image sources: