Download The Home Front during WWI: 1914-1918 Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach The Home Front during WWI: 1914-1918 to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Table of Contents

Add a header to begin generating the table of contents

Summary

- Background of the First World War

- The Home Front

- Recruitment and Conscription

- Role of Women

- Government Measures

- End of the War

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about the Home Front during WWI

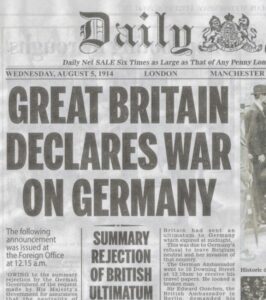

- On 4 August 1914, Great Britain officially declared war against Germany. The announcement followed the expiration of the ultimatum which sought to protect Belgium, France and the rest of Western Europe. Before the outbreak of war, Great Britain was known to have pursued the policy of splendid isolation. However, in the beginning of the 20th century, Great Britain formed alliances which later resulted in the establishment of the Triple Entente in 1907. Despite not being fought on British soil, the war involved the home front, dominions and colonies of the British Empire.

- Also known as the Great War, WWI was a military and political conflict between the Central Powers and Triple Entente, which began in 1914 and lasted until 1918. Historians suggest that the inevitability of war was brought about by complex factors. They included the alliance system, and the rise of militarism, nationalism and imperialism.

The Alliance System

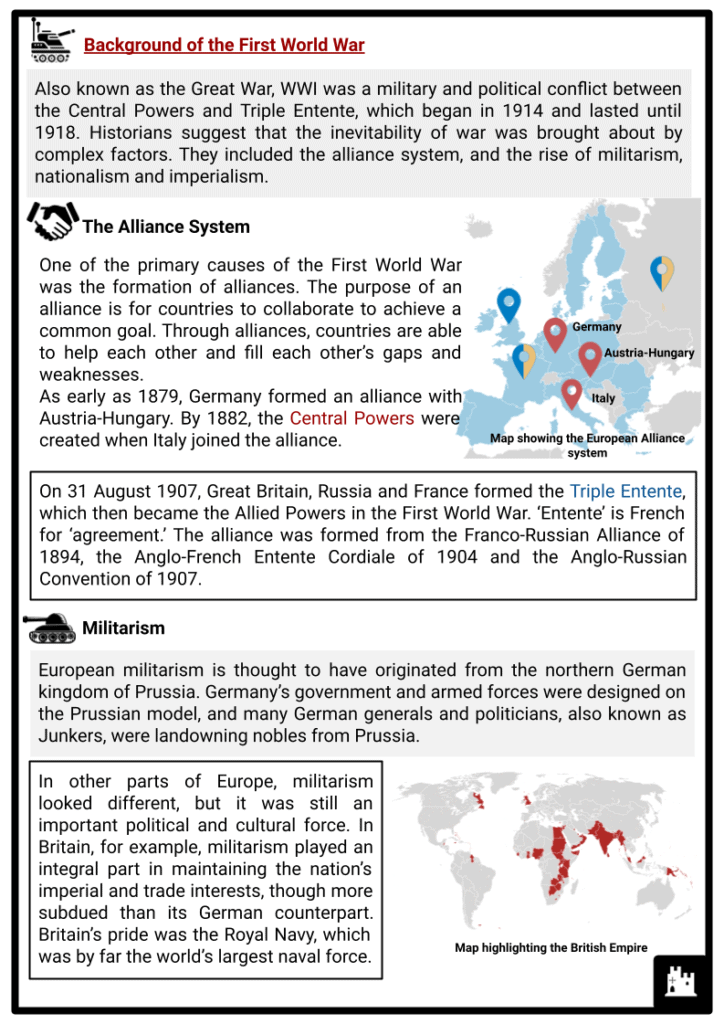

- One of the primary causes of the First World War was the formation of alliances. The purpose of an alliance is for countries to collaborate to achieve a common goal. Through alliances, countries are able to help each other and fill each other’s gaps and weaknesses.

- As early as 1879, Germany formed an alliance with Austria-Hungary. By 1882, the Central Powers were created when Italy joined the alliance.

- On 31 August 1907, Great Britain, Russia and France formed the Triple Entente, which then became the Allied Powers in the First World War. ‘Entente’ is French for ‘agreement.’ The alliance was formed from the Franco-Russian Alliance of 1894, the Anglo-French Entente Cordiale of 1904 and the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907.

Militarism

- European militarism is thought to have originated from the northern German kingdom of Prussia. Germany’s government and armed forces were designed on the Prussian model, and many German generals and politicians, also known as Junkers, were landowning nobles from Prussia.

- In other parts of Europe, militarism looked different, but it was still an important political and cultural force. In Britain, for example, militarism played an integral part in maintaining the nation’s imperial and trade interests, though more subdued than its German counterpart. Britain’s pride was the Royal Navy, which was by far the world’s largest naval force.

Nationalism

- Historians agree that one of the fundamental reasons behind the outbreak of World War I was the growth of nationalism in Europe. Such an idea was a result of Enlightenment thinking on equality, freedom and democracy.

- Following German unification in 1871, the leaders of Germany relied on these nationalist sentiments to consolidate and strengthen their newly formed nation and to gain public support. German militarism greatly backed nationalism.

- However, the unification of Germany, the speed of German armament and the self-righteousness of Kaiser Wilhelm II caused concern among British nationalists.

- Controlled by nationalists, England’s ‘penny press’ fuelled this rivalry by publishing incredible fictions about foreign intrigue, espionage, future wars and invasion by the Germans.

- The nationalist movement that had the biggest impact on the outbreak of war was by Slavic groups in the Balkans. Pan-Slavism was the belief that the Slavic people of Eastern Europe should be independent and have their own nation, and that they were a powerful force in the region.

Imperialism

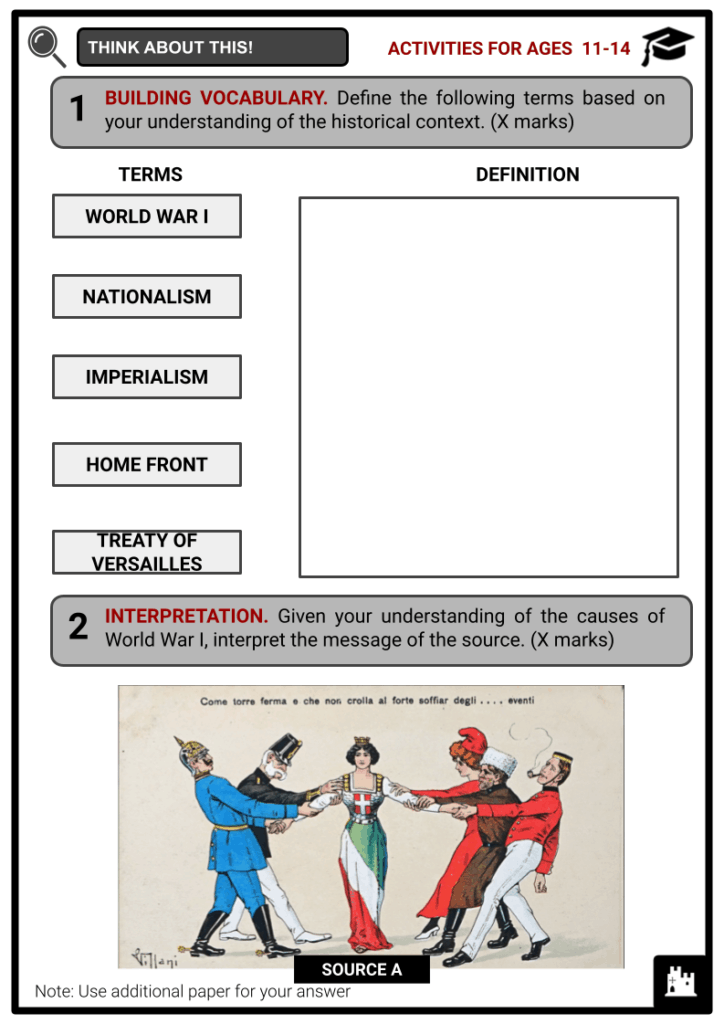

- Imperialism reached unmatched heights with European powers in the 19th century. European imperialism played a significant role in sparking WWI. Colonies were governed either directly by the imperial power, by a puppet government or by a local government of strategic individuals linked to the colonisers.

- During the 19th and 20th centuries, European powers held significant territories across the globe.

- The largest empire was Britain, which had control over Canada in the Americas, colonies in Africa spanning South Africa to Egypt, India and modern-day Sri Lanka and Burma on the Asian continent, the islands of Hong Kong, parts of the Caribbean and Pacific Islands, as well as the Oceanic nations of Australia, Tasmania and New Zealand, to name just a few.

The Home Front: Recruitment and Conscription

Prior to the outbreak of WWI, the British Army had around 80,000 regular troops ready for war. By 1914, around 710,000 men stood in reserve. By the end of WWI, almost 1 in 4 men in Britain had joined the military, totalling 2.67 million as volunteers, and 2.77 million as conscripts.

So what compelled so many men to join?

- Nationalism, which is an intense form of patriotism, was a prominent force during WWI. Nationalism exaggerated the value and importance of one’s home country, placing its interests above others.

- Many Britons were convinced of their cultural, economic and military supremacy and believed that this supremacy needed defending from Germany. Politicians, diplomats and royals contributed to this mindset in their speeches and rhetoric, while the media also played into it through its reporting.

- Sense of loyalty also saw the formation of 'pals battalions' in which groups of men from the same community, football team or factory joined together.

- Members of society were also effective in compelling men to sign up. Women, who had only just received suffrage, were very patriotic, and many actively shamed seemingly eligible men for not enlisting.

- The Derby Scheme was an experiment conducted in the autumn of 1915 to determine whether Britain could meet its WWI manpower goals through volunteers alone or whether conscription would be necessary. It was named after Lord Kitchener’s new Director General of Recruiting, Edward Stanley, 17th Earl of Derby.

- Canvassers, who were “tactful and influential men”, got men to enter the programme and they were handed a letter from Derby explaining they were in “… a country fighting, as ours is, for its very existence …” The outcome was that there were 318,553 medically fit single men, but 38% of them publicly refused to enlist. This left the government short, and conscription was introduced in January 1916.

- WWI conscription began after the passing of the Military Service Act in January 1916. This compelled all men between 18 and 40 (later increased to 51 years old) to be called up. A tribunal determined whether they were exempt. Due to the political situation in Ireland, conscription was only applied in England, Scotland and Wales.

- In the UK, conscription occurred in two periods. The first was from 1916 to 1920 for WWI, and the second was from 1939 to 1960 during and after WWII. The last conscripted soldiers left the service in 1963.

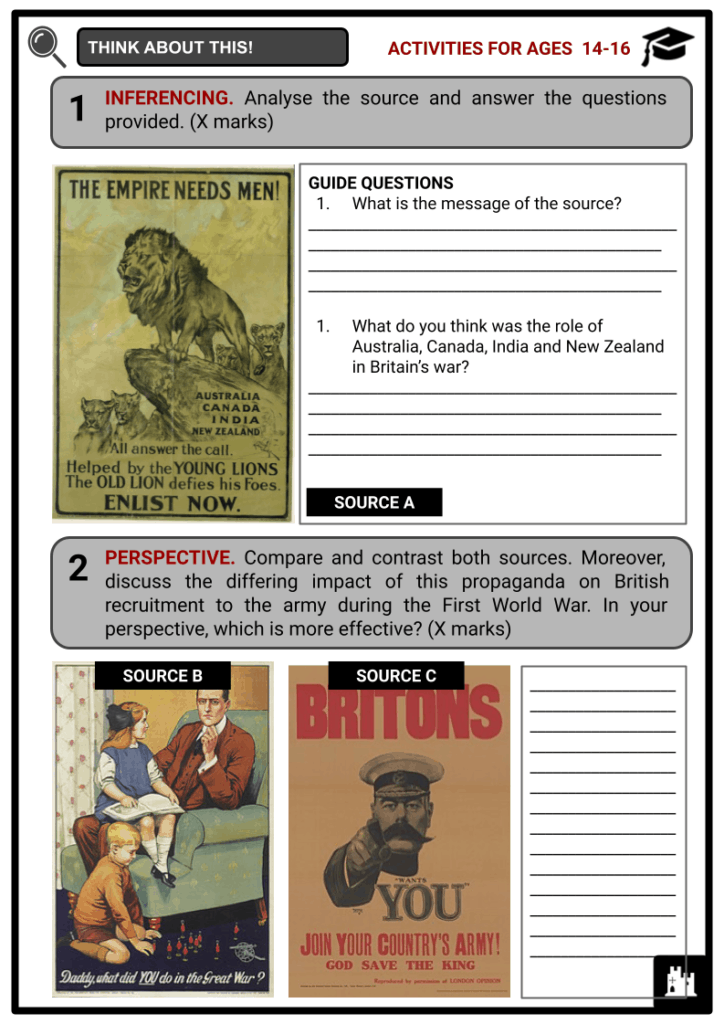

- The propaganda machine was highly successful in getting men to enlist. In 1914, the call for 100,000 volunteers was far exceeded with 500,000 men stepping up in two months. Around 250,000 underage boys also volunteered. England’s penny press was a cheap form of literature responsible for feeding into ideas of British supremacy by telling incredible fictions about foreign intrigues, espionage, future war and invasion. The penny press relied heavily on racial stereotypes such as Germans being cold, emotionless and calculating; Russians as uncultured barbarians; the French as leisure-seeking layabouts, etc.

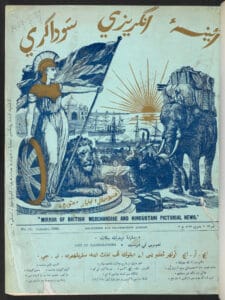

- Through the Neutral Press Committee and the Foreign Office, British propagandists sent special telegraphs to agencies in Bucharest, Amsterdam and Bilbao to spread information in other European countries. In London, the Illustrated London News published pictorial propaganda against the Germans. Issues were translated into Spanish, Portuguese, Greek and Chinese.

- In December 1915, Britain Prepared became the first prominent war film distributed worldwide. In August 1916, the film Battle of the Somme was released.

- The most common form of domestic propaganda was recruitment posters. Aside from urging the people to volunteer, posters included atrocity stories about a German invasion. Such stories were rooted in the German invasion of Belgium.

The Home Front: Role of Women

- Because of the introduction of conscription in 1916, the government launched campaigns and recruitment drives, as female workers were really needed. Large numbers of women took jobs left by men who had gone to fight in the war.

- New jobs were created as part of the war effort. For example, many women worked in munitions factories. In fact, it was one of the largest sources of employment in 1918.

- Women began to work ‘men jobs’ such as railway guards and ticket collectors, buses and tram conductors, postal workers, police officers, firefighters and as bank tellers and clerks.

- Some women worked on precision machinery in engineering, others led cart horses on farms or worked in the civil service and factories.

- Their wages were lower than men’s.

- In 1917, as the army was running out of men, the War Office decided that women could do some front line jobs that did not involve fighting. The Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) was organised into four units: cookery, mechanical, clerical and miscellaneous. Women could do work such as answering telephones and passing messages to soldiers, cooking for men in camps and hospitals, repairing broken down vehicles, etc.

- The Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps became Queen Mary's Army Auxiliary Corps (QMAAC) in 1918. More than 57,000 women served between January 1917 and November 1918.

The Home Front: Government Measures

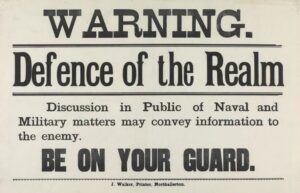

- On 8 August 1914, days after WWI began, the Defence of the Realm Act was passed. This act extended the wartime emergency powers of the British government. As a wartime measure, the government took control of the social, economic and industrial concerns in Britain.

- Under DORA, the government was allowed to pass war-related laws without the usual process of voting and ratification by Parliament. Wartime laws particularly aimed to maintain the morale of the people and increase production. It covered the following:

- Newspapers detailing information to and from the trenches were censored;

- To protect and maintain production on the Home Front, striking was outlawed.

- In order to increase production while maintaining expense, the working day was extended, particularly in agriculture. Loss of productivity at work and lateness were reprimanded.

- Prohibition on alcoholic drinks.

- The government also disallowed its citizens to do the following:

- Talk about military matters in public and spread rumours about war

- Light bonfires

- Feed bread to chickens or horses

- Use invisible ink when writing

- Melt silver or gold

- Initially, the public agreed to the measures employed by the government. However, as the war progressed, objections emerged as people thought that DORA undermined their freedom.

- Following the declaration of war, a rush of panic buying began. Anxious shoppers started hoarding food and other supplies. Despite the shortage of food, the government only intervened in 1916. Food rationing was introduced. Citizens were restricted from buying excess food and supplies. In January 1918, a national sugar rationing was also introduced. People were prohibited from buying more than one pound of sugar per week. Other goods included butter, margarine, meat, tea and bacon.

End of the war

- After the war, human and financial losses were experienced by many. Britons saw that little had been gained from the war. Many expected enormous punishment towards Germany and that Allied soldiers on the Western Front would be rewarded for their bravery.

- Due to collective efforts during the war, class distinctions in British society weakened. The public felt a great sense of loss which gave the idea of a lost generation.

- With the return of soldiers from the Western Front, some women who had paid jobs during the war returned to their domestic duties, while others remained in the workforce. Attitudes towards sex, smoking and drinking in public also changed.

- The war was followed by general economic and social unrest in Britain. Many came to question whether the war was really worth it.

- One of the greatest challenges the British government faced after the war was the state of its economy and fulfilment of war-time promises. Increase in taxation to fund education and housing policies created labour unrest in the 1920s.

- King George V of Great Britain, Tsar Nicholas II of Russia and Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany were all cousins and grandchildren of Queen Victoria.

- On 18 January 1919, the Big Four - British PM David Lloyd George, French Premier Georges Clemenceau, US President Woodrow Wilson and Italian PM Vittorio Orlando - met in Paris.

- About 30 nations attended the conference, while defeated countries - Austria-Hungary, Turkey, Bulgaria and Germany, were not represented.

- The Armistice of 11 November 1918 ended the conflict between the Allies and Germany, thereby ending WWI.

- It was prolonged three times until the Treaty of Versailles was signed on 28 June 1919, and took effect on 10 January 1920.