Download No Man’s Land Worksheets

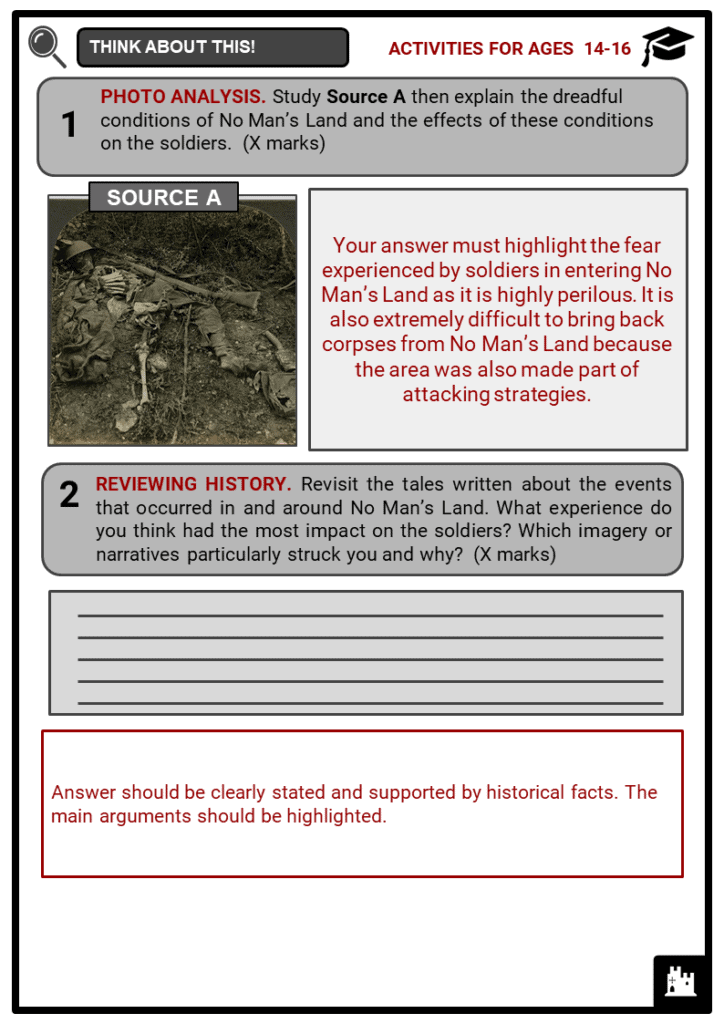

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach No Man’s Land to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Table of Contents

Add a header to begin generating the table of contents

Summary

- Definition of No Man’s Land

- Description of No Man’s Land during the First World War

- No Man’s Land in the present time

- No Man’s Land in literature and tales

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about No Man’s Land!

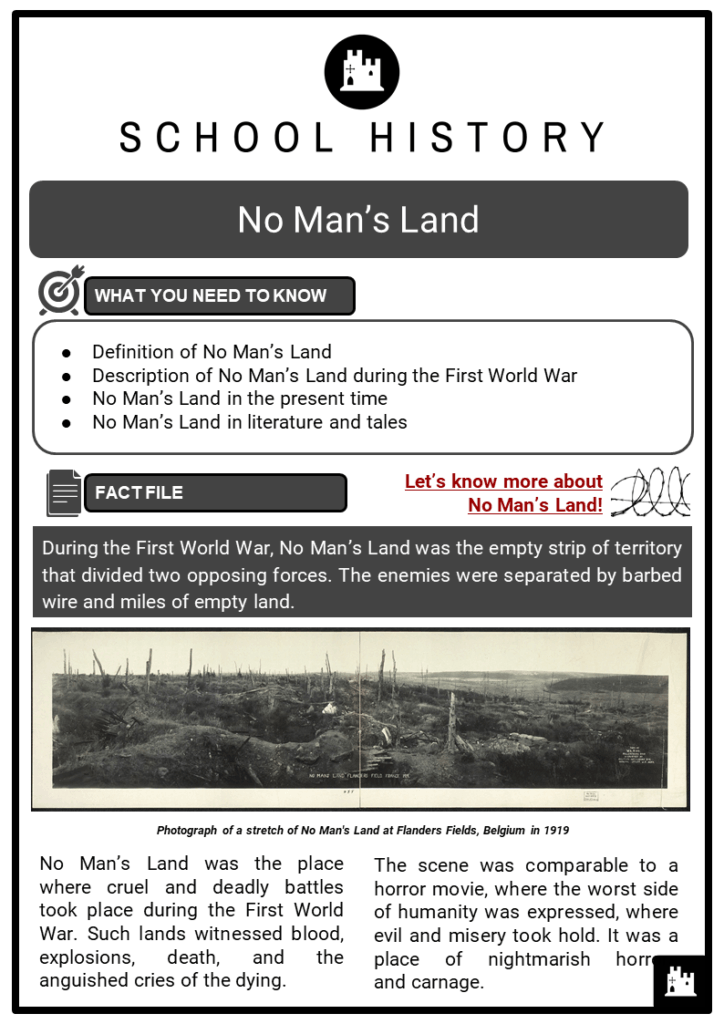

- During the First World War, No Man’s Land was the empty strip of territory that divided two opposing forces. The enemies were separated by barbed wire and miles of empty land.

- No Man’s Land was the place where cruel and deadly battles took place during the First World War. Such lands witnessed blood, explosions, death, and the anguished cries of the dying.

- The scene was comparable to a horror movie, where the worst side of humanity was expressed, where evil and misery took hold. It was a place of nightmarish horrors land carnage.

- Today there still exist good examples of No Man’s Land. One of them is the Zone Rouge in France, which forbids entry to unauthorised people because of the deadly chemicals it still contains.

Overview

- No Man’s Land is a term still used today to colloquially indicate ‘anywhere from derelict inner-city areas to spaces between borders, and even tax havens’. In essence, it is ‘a place where there has been an intentional withdrawal of state power and sovereignty’.

- The term “No Man’s Land” did not come into existence during the First World War. Rather, it was used over 1000 years ago and in fact was used during medieval times to ‘denote disputed territory’. At the outbreak of war in 1914, the phrase became more commonly used.

- No Man’s Land is the battlefield’s area ‘between two opposing fronts’ that is not controlled or governed by any of the two battling parties.

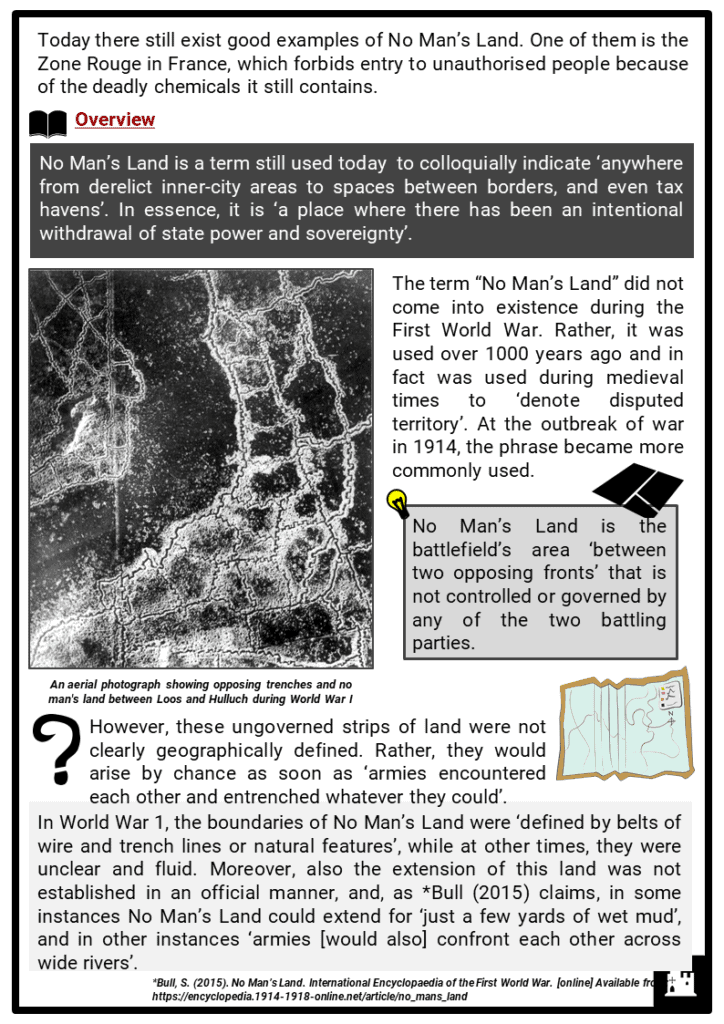

- However, these ungoverned strips of land were not clearly geographically defined. Rather, they would arise by chance as soon as ‘armies encountered each other and entrenched whatever they could’.

- In World War 1, the boundaries of No Man’s Land were ‘defined by belts of wire and trench lines or natural features’, while at other times, they were unclear and fluid. Moreover, also the extension of this land was not established in an official manner, and, as *Bull (2015) claims, in some instances No Man’s Land could extend for ‘just a few yards of wet mud’, and in other instances ‘armies [would also] confront each other across wide rivers’.

- Moreover, during World War 1, retrieving the dead or wounded from on No Man’s Land was not a simple task, since the empty strips of territory were used in attacks to ‘strike small demoralising blows’.

- This is also the reason why the First World War is defined as a static war: the presence of barbed wire fences meant that the battles often fell into stalemate, with none of the opposite forces advancing.

- Rather, each party stood in their own trenches and preferred attacking and striking their enemy from a distance. What separated the two battling factions’ trenches was an empty land, which offered the new experience of “empty battlefield”.

- In fact, both parties were ‘afraid to venture into’ No Man’s Land because of their ‘fear’ of what could happen if they did.

- Most of the activity in No Man’s Land went on during the night, when each side would spy on their enemies, or spend time repairing the barbed wire which divided them, or retrieving the bodies of dead or wounded soldiers.

What was in No Man’s Land

- In her book The Great War in Irish Poetry: W.B. Yeats to Michael Longley (2000), the author Fran Brearton provides her readers with a gruesome image of what No Man’s Land presented: ‘men [were] drowning in shell-holes already filled with decaying flesh, wounded men, beyond help from behind the wire, dying over a number of days, their cries were audible, and often unbearable to those in the trenches; sappers buried alive beneath its surface’

- Although No Man’s Land was an empty, ungoverned territory, it was nonetheless a scary place to be during the battles of the Great War. In fact, this land was treated as a weapon, and it was characterised by craters, ‘barbed edged wire and shredded tree trunks’. Over the course of the battles, the territory would become a wasteland characterised by ‘destroyed vegetation, mud-soaked craters, and rotting corpses’.

- The poet Wilfred Owen described No Man’s Land as being ‘like the face of the moon, chaotic, crater-ridden, uninhabitable, awful, the abode of madness’ .

- The war’s landscape also changed drastically. In fact, soldiers were no longer on horses ‘with rifles in lined formation’, rather, the dynamics and the looks of the war were characterised by ‘zombie-like figures in trenches’ fighting with ‘portable machine guns, explosives, tanks, flamethrowers, air raids, and gas’.

- Although it was a dangerous enterprise, during the war, some artists engaged in the practice of documenting the modes of battle in their art.

- With the development of photography, some of them were able to capture and ‘expose the starkly beautiful, apocalyptic landscapes’. An example of such landscapes is The Cursed Wood (1918), by Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson

No Man’s Land Today

- Across Europe there are still areas of No Man’s Land. One of the most dangerous ones is the Zone Rouge, a small area near Verdun in the centre of France. It is a virgin forest of around 460 miles2. Although historically it is exceptionally interesting, having witnessed the fierce and bloody battles of World War I, it remains to this day horrific and deadly. In fact, its access is restricted, and whoever manages to enter this abandoned area is not guaranteed survival.

- In 1918, at the end of the war, the French government realised that ‘it would take several centuries to completely see the area clear’. Some believe that it would take between 300 and 700 years to make the area safe and inhabitable once again.

- According to Shahan Russell in his article “The “Red Zone” In France Is So Dangerous that 100 Years After WWI It Is Still A No-Go Area”, although some areas of the Zone Rouge appear as an empty, harmless, ‘pristine forest’, it is nonetheless an insidious place that ‘hide[s] millions of explosives’ of which some have already ‘gone off’ and others are ‘just waiting for someone or something to set them off’.

- To this day, the authorised personnel from the Département du Déminage who enter the Zone Rouge find ‘weapons, helmets’ and skeletons.

- Moreover, it is necessary to keep in mind that during the First World War, weapons and explosives contained dangerous chemicals: in fact, the land contains high levels of mercury and zinc, and the arsenic levels reach 17% (which is 300 times more than what scientists deem ‘tolerable’). In essence, all those chemicals present in the Zone Rouge have ‘impact[ed] the soil and the groundwater of the region, resulting in patches where little grows and where animals die’.

- The presence of gas shells has a massive repercussion on human lives since ‘the build-up of toxins in the human body’ can take a while to be detected. Therefore, the areas surrounding the Zone Rouge are also highly dangerous and poisonous. And although some people attempt to exploit tourism in such historic venues by building restaurants and shops, they remain incredibly unsafe.

No Man’s Land: Literature and Tales

- The events on the battlefield during World War I fuelled horrific stories that recounted the ‘sinister, animalistic societies’ and the ‘cannibalistic lunatics’ that inhabited such areas.

- According to some tales, in No Man’s Land there were wild men (whose numbers ‘ranged anywhere from a battalion-sized group to regimental sizes’), that were made up of deserters of German, British, Canadian, Italian, French, Austrian and Australian nationality. They lived in subhuman conditions and they were described as being ‘ghostly pale, bearded men’ with scars on their faces, and they were either naked or ‘dressed in tattered, filthy uniforms’.

- The conditions they lived in were degrading since they had regressed to an animalistic state, for they ‘crept from their subterranean domain at night in order to scavenge weapons, food, shoes, and clothes off the bodies of the dead and dying’. Sometimes, they would also indulge in eating their corpses and/or fight with other men for their flesh.

- Moreover, numerous accounts can be found in various books, journals, and memoirs. For instance, Arthur Hulme Beaman talked about the wild deserted in his memoir The Squadroon (1920), in which he states that the officers and soldiers would often hear ‘inhuman cries and rifle shots coming from the awful wilderness as though the bestial denizens were fighting amongst themselves’.

- Similarly, in Walter Frederick Morris’s novel Behind the Lines (1930), the character Rawley was led underground by Alf (a deserter): ‘squeezed through the hole, feet first. He found himself in a low and narrow tunnel, revetted with rotting timbers and half-blocked with falls of earth. . . . The whole place was indescribably dirty and had a musty, earthy, garlicky smell, like the lair of a wild beast. . . . ‘Where do you draw your rations?’ asked Rawley. . . . ‘Scrounge it, [Alf] answered, . . . We live like perishin’ fightin’ cocks sometimes, I give you my word. . . . There’s several of us livin’ round ’ere in these old trenches, mostly working in pairs’ (Deutsch 2014; citing Morris 1930).

Image sources

[2.] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/ff/Battelfield_Verdun.JPG