Download Mary II of England Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach Mary II of England to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Table of Contents

Add a header to begin generating the table of contents

Summary

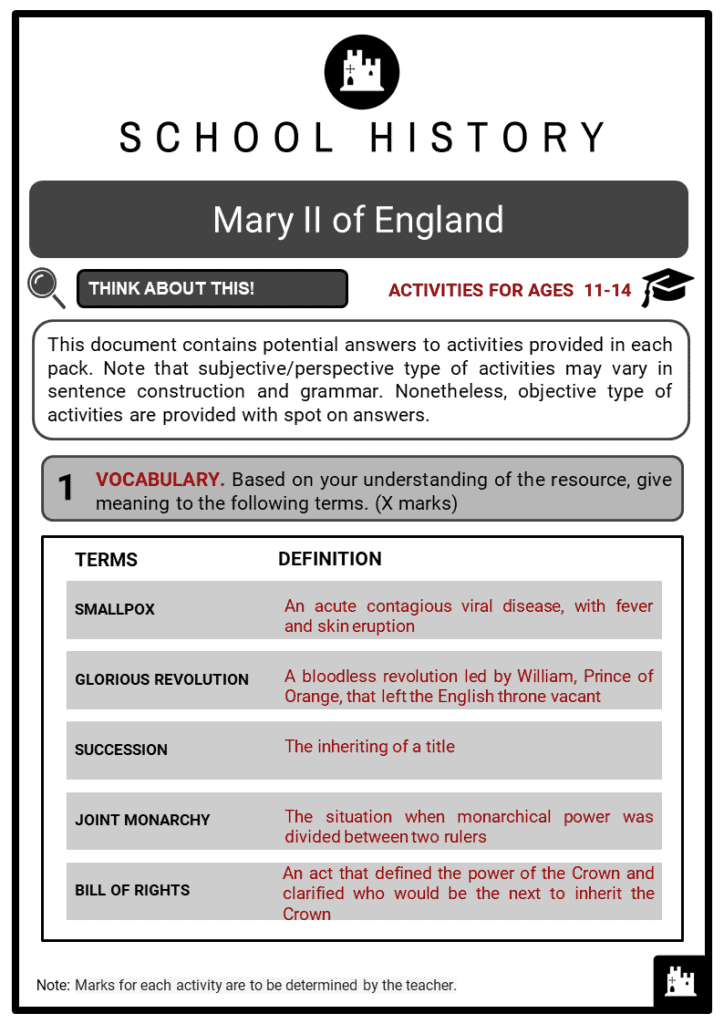

- Mary’s youth

- Marriage to William, Prince of Orange

- The reign of James II

- The Glorious Revolution

- The English Succession of William III and Mary II

- Death of Mary II

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about Mary II of England!

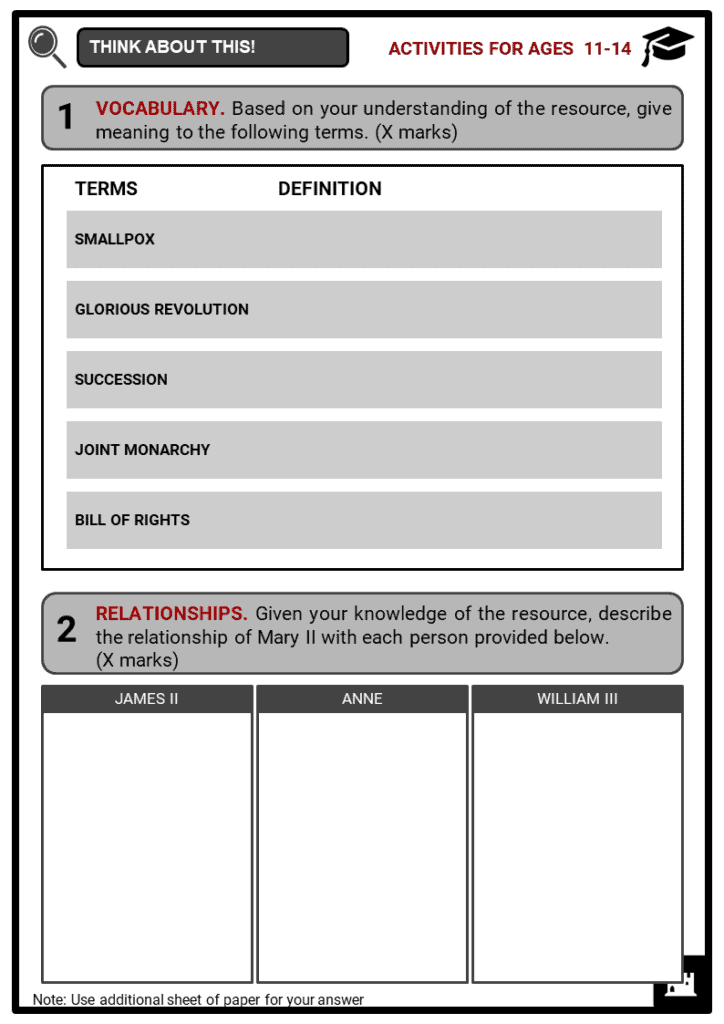

- Mary II was the Protestant Queen of England, Scotland and Ireland who reigned jointly with her husband, William III. Whilst her marriage with William, then Prince of Orange, initially brought her to tears, she went on to lead a contented and reserved married life in Holland for twelve years. Upon their succession to the English throne on 13 February 1689, William III and Mary II signed the Bill of Rights, which prevented the succession of Catholic monarchs and secured the Protestant kingdom.

Mary’s Youth

- Mary, who was born in London on 30 April 1662 at St. James’ Palace, was the eldest daughter of the Duke of York, the future James II of England and his first wife, Lady Anne Hyde.

- She was raised under the protection of her maternal grandfather, Edward Hyde, first Earl of Clarendon.

- Mary was baptised according to the Anglican rite and named after one of her ancestors, Mary of Scotland.

- Mary spent most of her childhood at Twickenham and Richmond Palace with occasional visits to her parents at St. James’ Palace.

- She was raised with her sister by the Protestant governess Lady Frances Villiers.

- Private tutors educated Mary and her studies consisted of music, dance, drawing, French and religion.

- Her father, the Duke of York, converted to Roman Catholicism in 1668 or 1669, whereas Mary and Anne were educated as Anglicans, in accordance with the dictates of Charles II.

- When Mary’s mother died in 1671, her father remarried two years later, taking Catholic Mary Beatrice of Modena, who was just four years older than Mary, as his second wife.

- From the age of about nine, Mary maintained close correspondence with an older girl, Frances Apsley, daughter of courtier Sir Allen Apsley.

Marriage to William, Prince of Orange

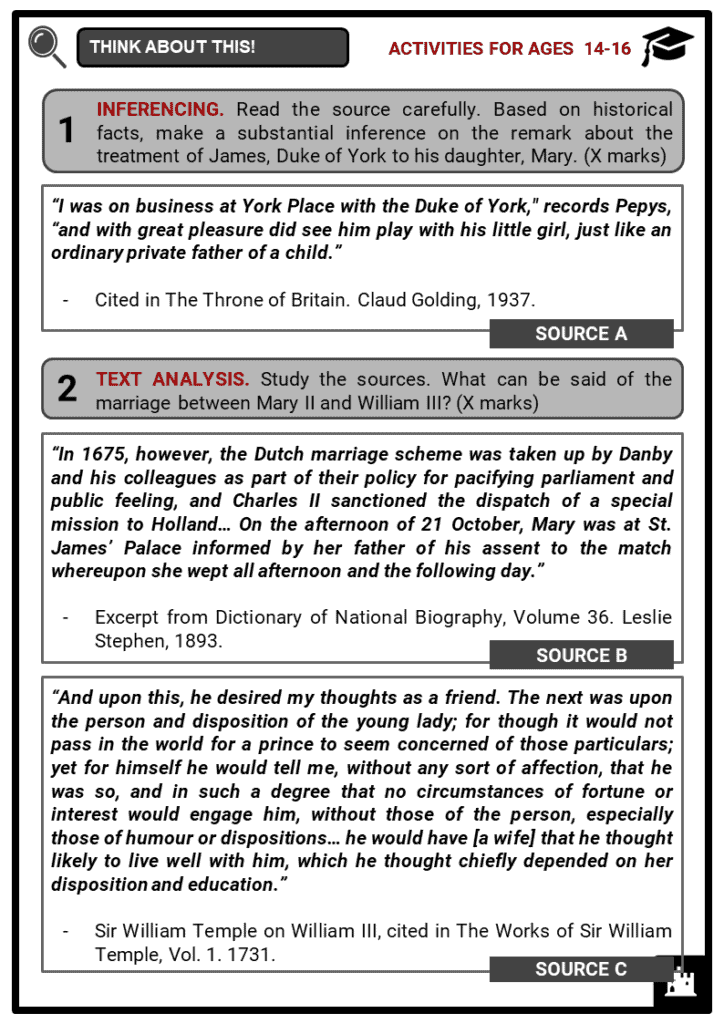

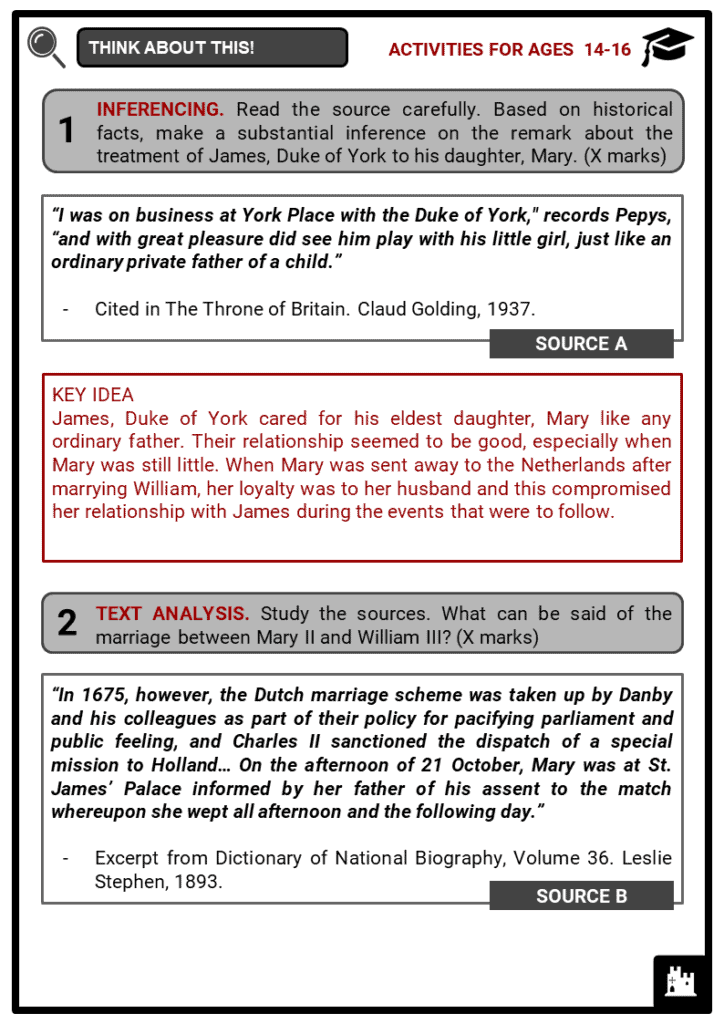

- At the age of fifteen, Princess Mary was betrothed to the Stadtholder of Holland, William, Prince of Orange.

- William was the son of her paternal aunt, Mary Stuart, and of Prince William II of Orange-Nassau.

- Initially, Charles II opposed an alliance with the Dutch ruler; he would have preferred Mary to marry the heir to the French throne, Louis.

- However, he subsequently approved and offered his nephew the hand of Mary.

- Holland was becoming politically favourable and William was known as the Protestant champion in Europe.

- Pressured by the Parliament, by the King, and by Lord Danby, the Duke of York consented to the union and told his daughter about the arranged marriage.

- Whilst she cried all afternoon and the following day, she agreed to obey the king.

- William and Mary were married in the chapel of St. James’ Palace by Bishop Henry Compton on 4 November 1677.

- William turned twenty-five on that day while the tearful Mary turned fifteen that year.

- The union was attended by King Charles II and Queen Catherine, the Duke of York and his young consort, Mary Beatrice.

- Anne’s illness also added to Mary’s sadness. Anne, being confined to bed due to smallpox, was prevented from assisting in her sister’s marriage.

- The illness proved fatal to Mary’s family: her uncle, Duke of Gloucester, and William’s mother died of it.

- In fact, half the household of St. James’ Palace was very ill at that time.

- Mary, as established by the marriage contract, would have followed her husband to the Netherlands, but the departure for Holland had to be delayed by almost a month because of bad weather that raged at sea.

- When the couple reached the Dutch coast, they were unable to access Rotterdam because the water around the port had completely frozen.

- As a result, the ship was forced to dock in the small village of Ter Heijde and the royal couple had to continue on foot through the snow until they reached a carriage that transported them to Huis Honselaarsdijk.

- Mary was saddened by her departure from England as a consequence of her marriage but found relief in the company of her faithful English friends.

- Mary arrived at Holland along with her party which included the three daughters of her childhood governess: Lady Inchiquin, Anne, and Elizabeth Villiers.

- Her husband took a mistress from these sisters, Elizabeth, which further provoked Mary’s sorrows that lasted throughout the marriage. For the next twelve years, Mary led a reserved married life in Holland.

- Mary’s lively nature made her popular with the Dutch people and her marriage to a Protestant prince immediately increased her family’s popularity in Britain.

- Whilst she was devoted and faithful to her husband, William did not demonstrate his affection to her and often appeared cold towards his wife.

- Within months of their marriage, Mary became pregnant.

- During a visit to her husband in the fortified city of Breda, she suffered a miscarriage that may have prevented her from having further pregnancies.

- She experienced further miscarriages in 1678, 1679 and 1680.

- From May 1684, the king’s illegitimate son, James Scott, the Duke of Monmouth, came to live in the Netherlands where William and Mary welcomed him.

- Monmouth was seen as a rival of the Duke of York at the English court.

- William, on the other hand, welcomed him positively, believing that he was a strong Protestant ally.

The Reign of James II

- When Charles II died without legitimate heirs on 6 February 1685, the Duke of York became king and was named James II (in England and Ireland) and James VII (in Scotland).

- James II wrote a letter to his daughter Mary bearing the news about Charles II’s death and his accession to the throne.

- When the letter arrived at the Hague, William read it aloud to the Dutchmen while they were dining in public.

- Monmouth left Hague by night upon hearing the news.

- When Monmouth assembled troops in Amsterdam intending to invade Great Britain, William of Orange informed his father-in-law of his intentions and ordered the British regiments in the Netherlands to return home.

- Thanks to William’s readiness, the Duke of Monmouth was defeated, captured and executed. The king and Mary publicly deplored these actions, however.

- James, who grew increasingly unpopular in England, held a controversial pro-Catholic policy: his attempt to guarantee religious freedom even for non-Anglicans by suspending parliamentary laws by royal decree was not well received.

- Mary believed that her father’s actions and choices were unlawful.

- Moreover, James encouraged Mary to divorce William and convert to Catholicism. Mary, being faithful to Protestantism and her vows to William, rejected her father’s proposals.

- Her support for the exiled French Huguenots in Holland, who were driven out upon the Catholic King of France, Louis XIV’s revocation of the Edict of Nantes, showed her opposition to her father’s policy and her loyalty to her religion.

- In an attempt to damage the reputation of his son-in-law, James II encouraged his daughter’s staff to inform her that William had an affair with Elizabeth Villiers.

- Armed with this information, Mary waited outside Villiers’ room and caught her husband leaving it in the middle of the night.

- William denied amoury or adultery and Mary either believed him or decided to forgive him.

- Nevertheless, Mary sent her staff back to Britain.

- It is possible that Villiers and William were more likely meeting secretly to discuss diplomatic intelligence, in which Villiers was involved at the level of espionage.

The Glorious Revolution

- Following the political and social policy entertained by James II in England, several Protestant politicians and nobles came into contact with Mary’s husband as early as 1686.

- After James had forced the Anglican clergy to read the Declaration of Indulgence – the proclamation guaranteeing religious freedom to dissidents – his unpopularity grew significantly.

- Public alarm increased in June 1688, when Queen Mary of Modena gave birth to James Francis Edward Stuart.

- Unlike Mary and Anne, he was raised Roman Catholic.

- Some accused the king of secretly replacing his son, who died at birth, with another baby.

- Although there was no evidence to support this accusation, Mary publicly challenged the child’s legitimacy, breaking the close relationship she had with her father.

- On 30 June, William of Orange – who was still in the Netherlands with Mary – was invited to travel to England with an army to dethrone his father-in-law, James II.

- William was initially reluctant.

- Determined to prevent the Catholic succession that James II was conspiring, William agreed to proceed with the invasion, declaring that his intention was for the assembly of a free and lawful Parliament.

- Mary expressed her disinterest in political power but showed support for her husband’s expedition.

- In November 1688, William arrived in England with a force of fifteen thousand men and with the backing of Mary’s sister, Anne, the English army and navy.

- On 11 December, the defeated king tried to escape.

- He was intercepted but he managed to escape on his second attempt at flight on 23 December.

- William, not wanting to create conflict with his father-in-law, allowed James to flee to France, where he lived in exile until his death.

The English Succession of William III and Mary II

- The English throne was declared vacant: the Prince and Princess of Orange were elected as joint sovereigns.

- Mary’s arrival at the British dominions was welcomed with great rejoicing: people were celebrating throughout London’s streets and a puppet dressed as James II’s son was cast into flames to signify their hatred towards the queen’s rival.

- It was the first record in history of an execution of a baby’s effigy.

- In 1689, William of Orange convened Parliament to discuss who should succeed to the throne of England.

- A party led by Lord Danby believed that Mary should reign, since she was James II’s legitimate heir.

- However, William and his supporters believed that the Prince of Orange should not be subordinate to his wife and he should rule as king.

- England had already witnessed a joint monarchy in the 16th century when Mary I married the Spanish Prince Philip.

- At that time, it was agreed that Philip would take the title of king only until the death of his wife.

- The Parliament did not offer the crown to James Francis Edward Stuart, James’ son with Mary Beatrice.

- On 13 February 1689, William III and Mary II were proclaimed King and Queen of England after signing the Bill of Rights.

- In this instance, William was granted to remain king even after Mary’s death.

- Although some proposed that Mary be the sole ruler, Mary chose to rule by her husband’s side.

- The Bill of Rights later excluded not only James II and his heirs (with the exception of Anne) from the throne but all Catholic sovereigns.

- The Bill of Rights set out the wrongs committed by James II, the clauses that limited the power of the Crown, and the rights of English citizens.

- The coronation took place in Westminster Abbey on 11 April 1689, and news arrived that James II had taken possession of Ireland with the exception of Londonderry.

- James II wrote to Mary, which further divided them: he denounced and wished ill of his daughter’s coronation.

- Her estrangement from her father troubled Mary during her reign.

- In fact, Mary refused to take control of the government and noted: My heart is not made for a kingdom and my inclination leads me to a retired life, so that I have need of the resignation and self denial in the world, to bear with such a condition as I am now in.

- Rebellions arose in Scotland and Ireland, and in the same month of their coronation, England was again at war with France. William had to leave the governing to Mary.

- In June 1690, the Parliament passed the Regency Act, which gave full regnal powers to Mary while William was leading the army against France.

- Nine noblemen who were called regents assisted the queen.

- Whilst Mary ruled alone from 1690-1694, she also depended on her husband’s advice.

- Mary gave up governing when William returned from his campaigns and instead focused on redecorating royal palaces including Kensington Palace, cultivating royal gardens, and organising dress balls which displayed her Dutch tastes.

- Her relations with her husband, the government, and the English populace improved during her reign but not her relationship with her sister Anne.

- Anne left the court when John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough, who was the husband of Anne’s best friend, Sarah Jennings Churchill, was arrested and accused of planning to restore James II to the English throne.

Death of Mary II

- In November 1694, William returned from his campaigns and Mary was suffering from a virulent attack of smallpox.

- The queen remained calm when she knew that her death was looming.

- The king was inconsolable when the illness worsened. When it became apparent that the queen was dying, he fainted, to the horror of his attendants.

- Mary took her last breath on 28 December 1694 at the age of thirty-two in Kensington Palace.

- The people of England mourned her death and William was in a state of depression.

- Mary II was laid to rest in Henry VII’s chapel in Westminster Abbey on 5 March 1695.

Image sources:

[2.] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/bf/William_and_Mary.jpg