Key Facts & Summary

- The Great Plague was an epidemic that spread in England between 1665 and 1666.

- It led to the deaths of between 75,000 and 100,000 people, which was more than a fifth of the entire population of London at the time.

- Historically, it was believed that the disease was an infection of bubonic plague caused by the spread of a bacillus called Yersinia pestis transmitted through the bites of fleas (Xenopsylla cheopis) living on black rats, or through the bite of rats or other rodents.

- The plague of 1665-1666, however, spread in a reduced manner compared to the Black Plague that struck Europe between 1347 and 1353.

The living conditions in England

The plague appeared very early in the country – in the summer of 1348 – and never really disappeared from the British Isles. However, at that time, people thought they could survive by avoiding it.

In 1665, everything changed since the Black Death – as people called it – became very worrying. It was finally stopped thanks to another misfortune that happened in the city of London: the Great Fire of 1666, which destroyed the areas of the city most infected by the plague. It is estimated that the plague caused the deaths of 100,000 victims (i.e. between 15% and 20% of the population of the city at the time).

The year 1665 was marked by a scorching summer. As the population in London continued to grow, many lived in poverty and squalid conditions. Indeed, the only way for people to get rid of their waste was to throw it out of their windows onto the street. The city of London was, therefore, very dirty and an ideal habitat for rats.

During the resurgence of the plague, it was believed that cats and dogs were responsible for transmitting the disease. The Mayor of London, therefore, decided to eliminate all of them, which meant fewer predators of rats. Daniel Defoe – in his book Journal Of The Plague Year – states that about 40,000 dogs and 200,000 cats died in vain since the plague did not come from them but from the fleas that were transported by rats.

Naturally, the first victims of the plague were the people living in the most precarious and miserable conditions. These people lived in slums and could not avoid contact with rats nor avoid contact with infected people.

The nursery rhyme below refers to the plague of London and is symbolic of the disease’s symptoms:

Ring-a-ring of roses,

A pocketful of posies,

Attischo, Attischo,

We all fall down.

The first line references the red spots that developed on the skin of victims. It could also be a reference to the pus-filled buboes under the armpits or groin. The second line refers to another belief that the plague was spread through miasma – that bad smells were the cause of disease. It was thought that if one carried scented flowers or herbs in one’s pocket, one would be protected from miasma.

The last symptom of the plague was a sneezing attack that usually led to death. However, most of the victims did not even reach that stage and died well before. The plague was almost always fatal.

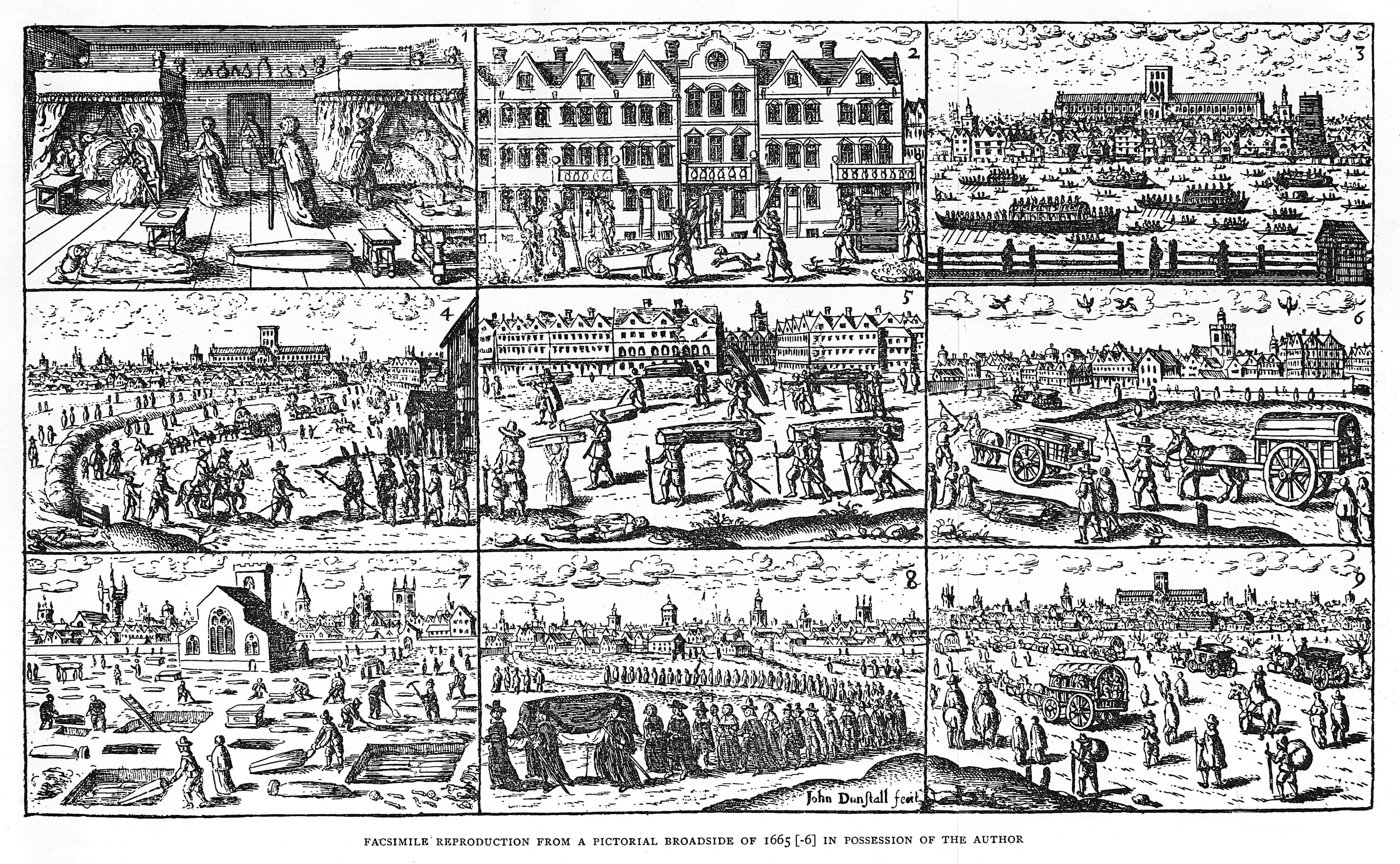

When the plague began to spread, healthy people who could afford to began rapidly abandoning the city. In June, the roads were filled with sick individuals and the Mayor responded by closing the gates, forbidding people without a certificate that testified good health from leaving London. These certificates became highly sought after and many fake ones started to circulate.

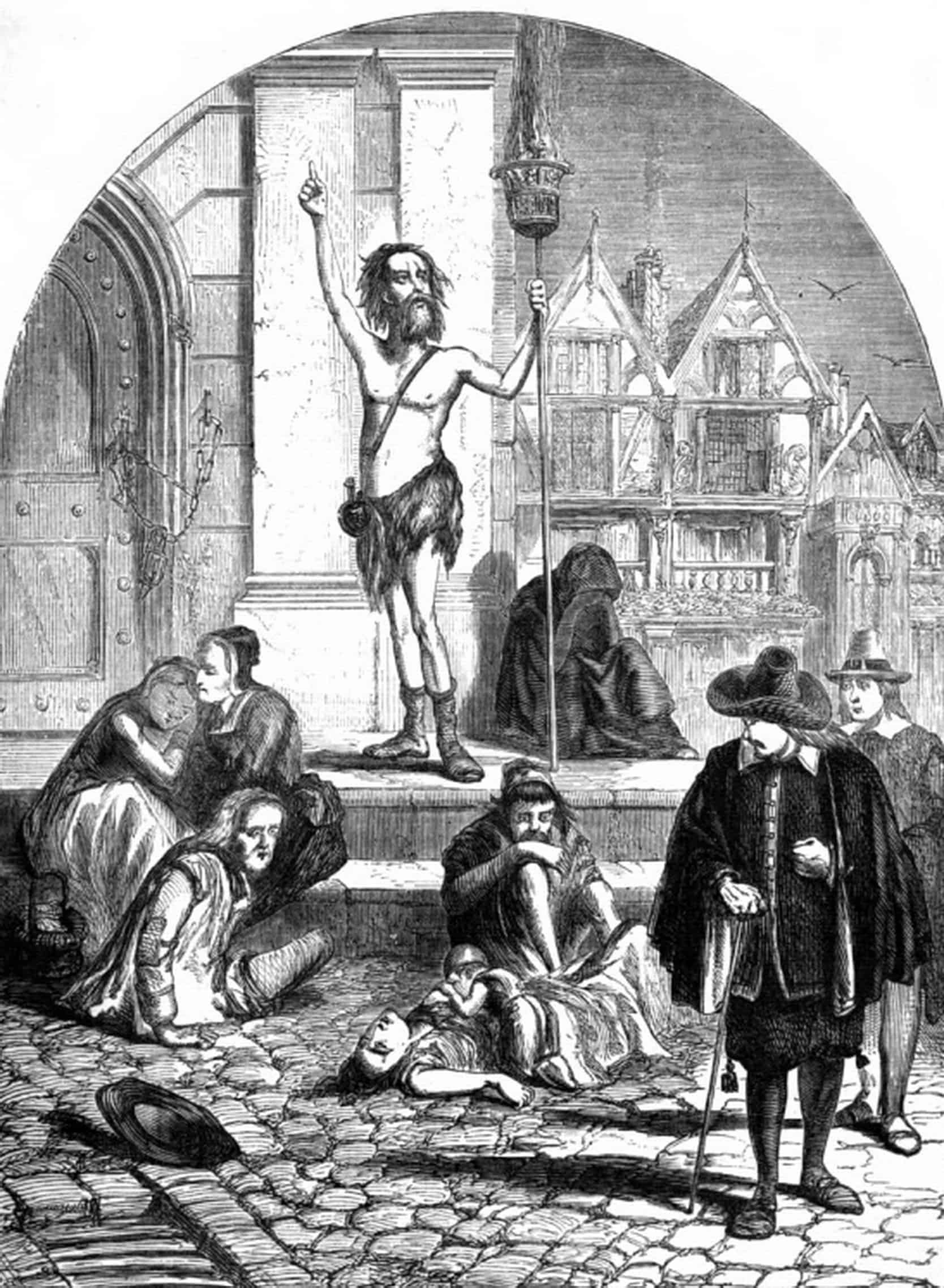

The poor were the most affected by the plague and London authorities decided to take drastic measures to prevent the disease from spreading further. All families whose members were affected by the disease were quarantined in their homes with a ban on going out. The house was chained from the outside and a red cross was painted on the door in order to warn others. The only people who were allowed in were nurses and doctors.

In reality, the ‘nurses’ had no medical training and were local women who were paid to visit the infected houses. Thus, they went to see how the victims felt and brought food to those who could afford it. Some people condemned this practice since a few of these nurses took advantage of their status in order to steal goods from the houses they visited.

Other people were paid to bury the bodies that the London authorities found. The unfortunate victims were loaded on a cart and thrown into mass graves. Other people were in charge of removing dogs and cats (which were considered responsible for the disease).

The plague reached its peak in September 1665, when the summer’s heat became unbearable.

More data of the mortality rate of the Great Plague is available than the Black Death thanks to a practice that was introduced before it struck: Every week, every parish in the city was required to maintain a Bill of Mortality, which was a written list of the dead.

Possible causes of the Plague

It is thought that the plague was carried to England by the Dutch ships trading cotton from Amsterdam. Since 1654, various areas of the Netherlands had been affected by a similar disease.

The areas outside London were the first to be affected by the spread of the plague. During the winter of 1664-1665, many contracted the disease and died. However, the winter was cold enough and the plague was contained with ease.

With the arrival of spring and summer, which had been particularly warm that year, the plague began to spread rapidly and on a large scale.

The Great Plague

In July 1665, when the plague was already spreading in London. King Charles II and the royal family decided to move to Oxford (an area which had remained untouched by the infection). By contrast, the Mayor of London and the council remained in the city. Many commercial enterprises came to an end due to the low amount of merchandise and the disappearance of merchants. Only a small number of clergy, doctors, and pharmacists stayed in London with the intention of helping overcome the plague. These individuals included the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Bishop of London.

Those who remained tried to stop the infection from spreading. They used flaming torches night and day, believing it would keep the air clean, and spices such as pepper and resins were used as incense to combat miasma. In addition, the authorities urged citizens to consume tobacco.

London was not the only city in England to be struck by the plague. The most famous is the case of Eyam village in the Derbyshire region, where the plague was carried by a trader who transported cotton bought in London: despite efforts to contain the infection, over 70% of the population died.

Contemporary sources report over one thousand deaths per week. Such accounts then increased to two thousand, and, in September 1665, reached seven thousand victims per week. At the end of autumn, the contagion began to subside and the king and the court were able to return to the city. Episodes of plague continued for several months until the outbreak of the Great Fire, which devastated much of the city of London.

Samuel Pepys’ quotes on the Plague

Samuel Pepys (1633-1703) was raised in bourgeois family. He was educated at Magdalene College, Cambridge. A cousin of his father (Edward Montagu) adviser to Cromwell, hired him as secretary. When Cromwell lost his power in 1659, Pepys participated in the restoration of the monarchy. This earned him a very important position in maritime affairs. He developed the naval capacity of his country and obtained the post of secretary of the admiralty. He also held a seat in Parliament. He fell out of the king’s graces in 1679, after being unjustly involved in a murder case.

Pepys was also president of the Academy of Sciences from 1684 to 1685. He abandoned politics in 1689.

Samuel Pepys kept a diary between 1660 (when he was 27 years old) until 1669. In order to keep it secret, he wrote it in a coded language known as tachograph, a form of shorthand. In his diary, Samuel Pepys gives us an inestimable testimony about the plague. Here are a few quotes from his journal:

April 30, 1665

‘Great fear of the sickness here in the City, it is being said that two or three houses are already shut up. God preserve us all’.

June 7, 1665

‘This day, much against my will, I did in Drury Lane see two or three houses marked with a red cross upon the doors, and ‘Lord Have Mercy upon Us’ writ there – which was a sad sight to me, being the first of the kind… that I ever saw. It put me into an ill conception of myself and my smell, so that I was forced to buy some roll tobacco to smell and chew, which took away the apprehension.’

June 10, 1665

‘To bed, being troubled by sickness, and particularly how to put my things and estates in order, in case it should please God to call me away.’ (Pepys feared he had contracted the disease).

June 15, 1665

‘The town grows very sickly, and people are afraid of it’.

Bibliography

[1.] Arnold, C. (2006). Necropolis: London and its dead. London: Simon and Schuster.

[2.] Moote, A.L. (2008). The Great Plague: The Story of London’s Most Deadly Year. London: JHU Press.

[3.] Pepys, S. (1665). Samuel Pepys Diary – Plague Extracts. Available from: http://www.pepys.info/1665/plague.html

Image sources:

[3. ] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/dd/Plague_in_London%2C_1665_Wellcome_M0010582.jpg