Download Third Italian War of Independence Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach Third Italian War of Independence to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Table of Contents

Add a header to begin generating the table of contents

Summary

- Prelude to the war

- The alliance with Prussia

- Timeline of the war

- Aftermath of the war

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about The Third Italian War of Independence

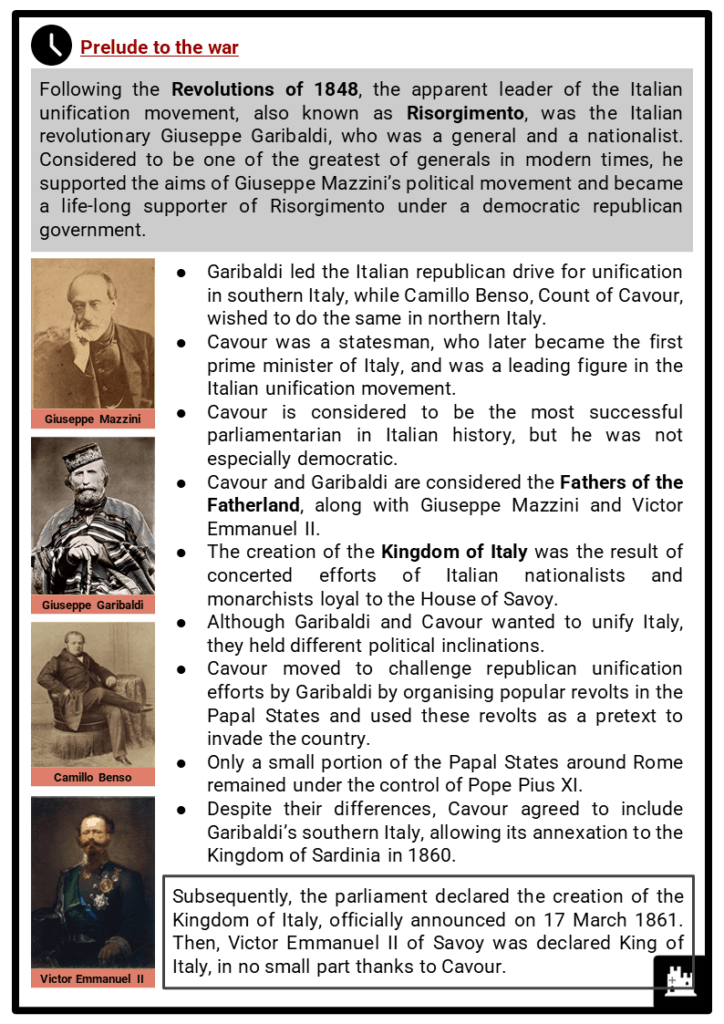

- Following the Second Italian War of Independence, the Kingdom of Italy, which comprised most Italian states except Venetia and the much reduced Papal States, was proclaimed in 1861. In June 1866, Italy, now allied to Prussia, declared war on Austria, commencing the Third Italian War of Independence. Parallel to the Austro-Prussian War, the conflict ended in Austrian defeat which eventually resulted in the cession of Venetia to Italy.

- The acquisition of this territory marked a major step in the process of Italian unification, owing to the Prusso-Italian alliance and the collective effort of the leading figures of Risorgimento such as Giuseppe Garibaldi, Count Cavour and Victor Emmanuel II.

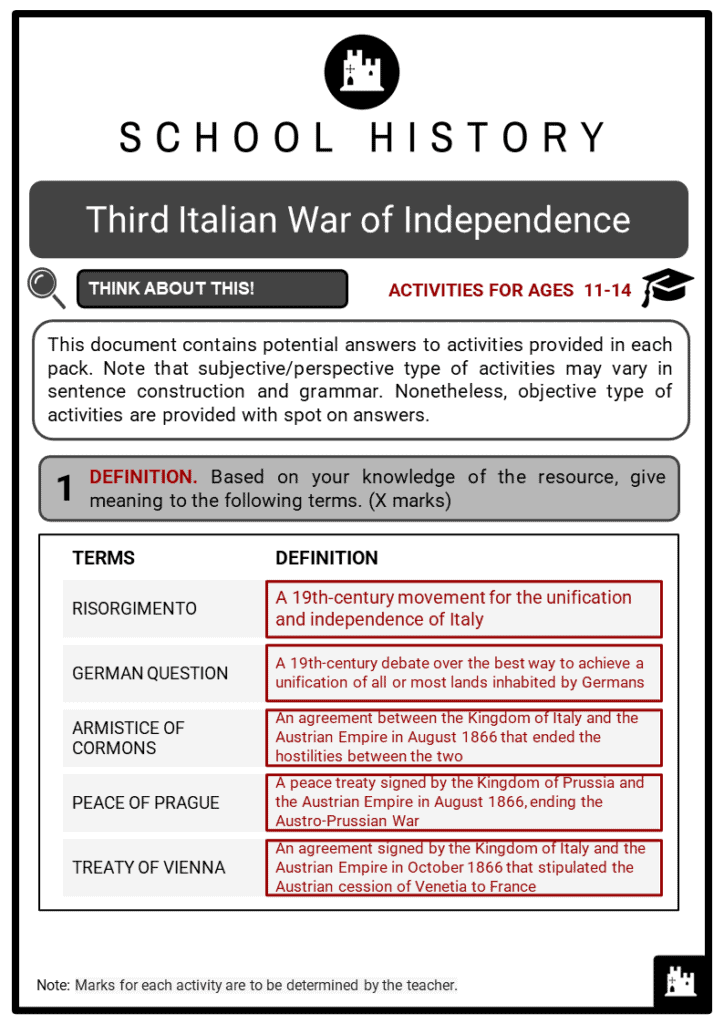

Prelude to the war

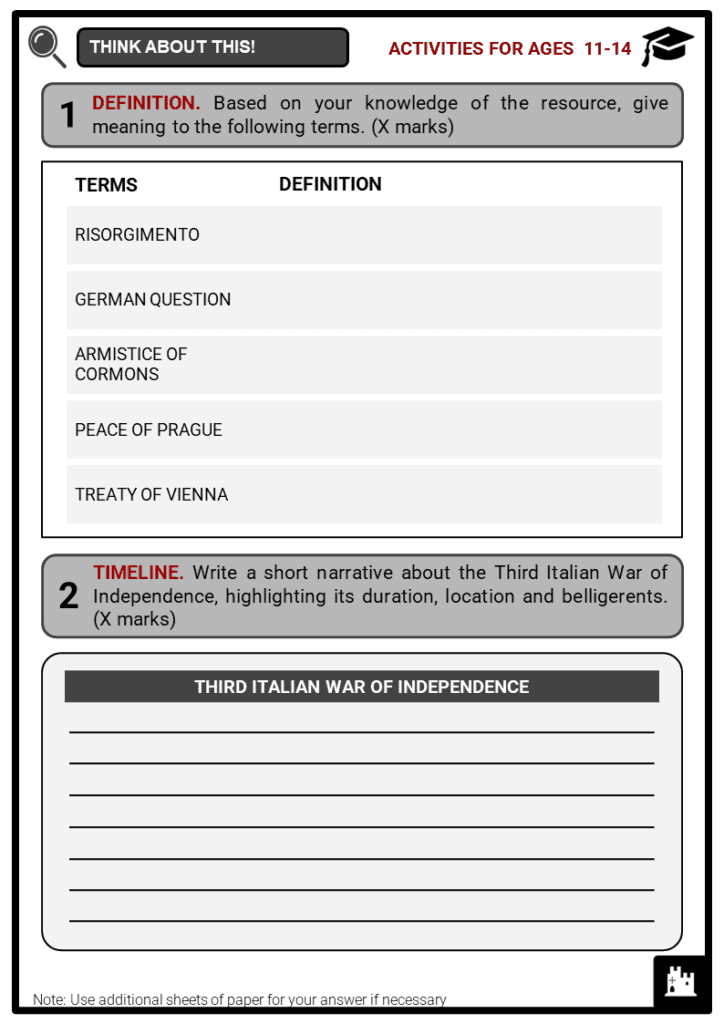

- Following the Revolutions of 1848, the apparent leader of the Italian unification movement, also known as Risorgimento, was the Italian revolutionary Giuseppe Garibaldi, who was a general and a nationalist. Considered to be one of the greatest of generals in modern times, he supported the aims of Giuseppe Mazzini’s political movement and became a life-long supporter of Risorgimento under a democratic republican government.

- Garibaldi led the Italian republican drive for unification in southern Italy, while Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour, wished to do the same in northern Italy.

- Cavour was a statesman, who later became the first prime minister of Italy, and was a leading figure in the Italian unification movement.

- Cavour is considered to be the most successful parliamentarian in Italian history, but he was not especially democratic.

- Cavour and Garibaldi are considered the Fathers of the Fatherland, along with Giuseppe Mazzini and Victor Emmanuel II.

- The creation of the Kingdom of Italy was the result of concerted efforts of Italian nationalists and monarchists loyal to the House of Savoy.

- Although Garibaldi and Cavour wanted to unify Italy, they held different political inclinations.

- Cavour moved to challenge republican unification efforts by Garibaldi by organising popular revolts in the Papal States and used these revolts as a pretext to invade the country.

- Only a small portion of the Papal States around Rome remained under the control of Pope Pius XI.

- Despite their differences, Cavour agreed to include Garibaldi’s southern Italy, allowing its annexation to the Kingdom of Sardinia in 1860.

- Subsequently, the parliament declared the creation of the Kingdom of Italy, officially announced on 17 March 1861. Then, Victor Emmanuel II of Savoy was declared King of Italy, in no small part thanks to Cavour.

The alliance with Prussia

- Although most states of the Italian peninsula were united and the Kingdom of Italy was created, Venetia and the much reduced Papal States were still far from their control. As such, the situation of the Irredente, a term referring to part of the country being under foreign domination, was a continuous source of tension in the domestic politics of the newly created kingdom.

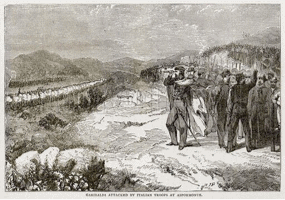

- An attempt to seize Rome was orchestrated by Giuseppe Garibaldi in 1862. He was confident of the king’s neutrality and set sail from Genoa to Palermo.

- He gathered 1,200 volunteers and went off to Rome but was stopped by General Enrico Cialdini.

- Cialdini sent a division under Colonel Pallavicino and when the two sides met, Garibaldi ordered his men not to shoot at Pallavicino’s division, as they were fellow Italians.

- Though they were fired upon at the Battle of Aspromonte and Garibaldi was wounded and taken prisoner along with his fellow volunteers, they were later released.

- The growing tension between Austria and Prussia over the German Question evolved into open war in 1866, granting an opportunity for Italy to attempt a seizure of Venetia.

- The German Question refers to the best way to achieve the unification of Germany: whether only the northern states of Germanic ethnicity should unite, or whether the unification should be comprised of all German states, including Austria that consisted of various different ethnicities and cultures.

- In the end, the Kleindeutschland, or the Lesser Germany solution – essentially Germany without Austria – won the votes and thus sparked the Austro-Prussian War.

- The German state of Prussia was aware of the tensions provoked by Austria’s presence in Venetia, and the Italian government was seeking an ally against Austria.

- The conflict between Austria and Italy was seen as an obstacle to complete unification for both countries.

- On 8 April 1866, the Italian general Alfonso La Marmora entered into an agreement with Otto von Bismarck, the Prussian prime minister.

- Italy would now vow to support Prussia in the case of war against Austria.

- Realising the brewing threat, Austria held out an olive branch to Italy by offering the transfer of Venetia.

- Faced with a difficult choice, La Marmora tried to stall and decided not to support a war against either Prussia or Austria. Prussia, on the other hand, would not wait and on 12 June, cut all ties with Austria and invaded some of its territories four days later. Italy finally joined the battle on 23 June.

Timeline of the war

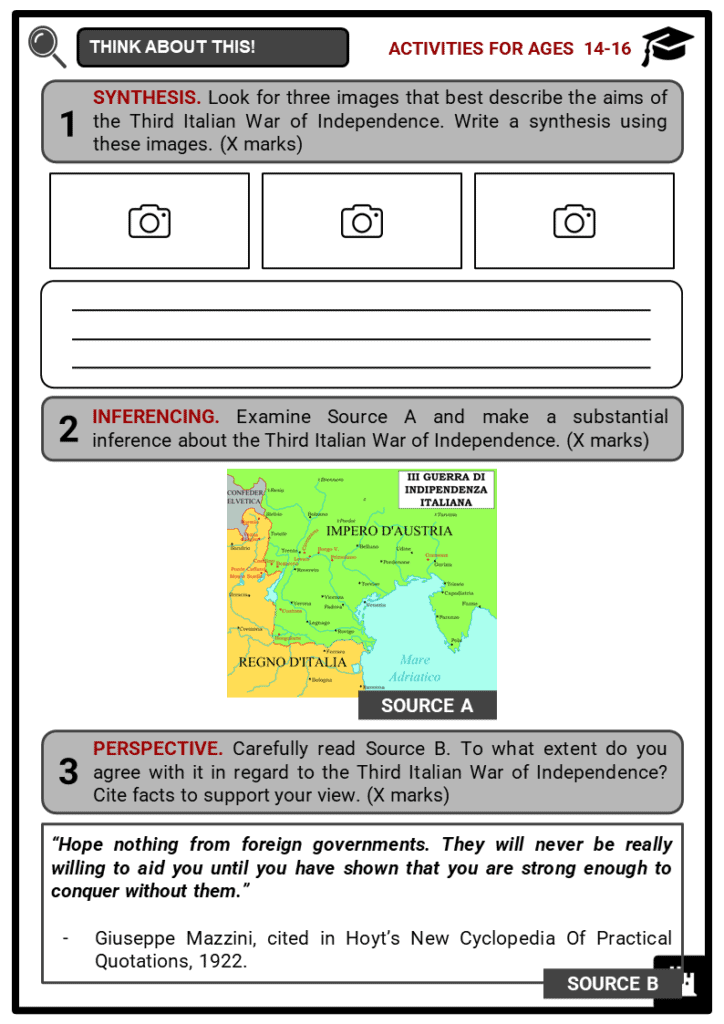

- During the Third Italian War of Independence in 1866, the Italian forces were divided into two armies. One was led by Victor Emmanuel II and La Marmora while the other was led by General Enrico Cialdini. They made up a plan of attack, consisting of two separate military interventions in two different areas of the Lombardo and Veneto.

- Communication between the two forces, however, was poor and the lack of coordination sufficiently weakened La Marmora’s grand plan. On 24 June, Italy suffered a major defeat at the Battle of Custoza, in the province of Verona. La Marmora retreated in disorder back across the Mincio River.

- Cialdini, on the other hand, did not act offensively for the first part of the war, conducting only several shows of force, and failed to besiege the Austrian fortress of Borgoforte, south of the Po River.

- Following the defeat at Custoza, the Italians reorganised in preparation for a presumed Austrian counter-offensive. The Austrians took this opportunity to raid Valtellina and Val Camonica.

- Despite beginning with a defeat, the situation would turn in Italy’s favour thanks to Prussian victories in Bohemia, especially the decisive Battle of Königgrätz (or Sadowa) on 3 July. The Austrians suffered heavy casualties, lacking artillery and cavalry cover.

- An important factor that contributed to their casualties was their earlier refusal to sign the First Geneva Convention in 1864. As a result of this decision, Austrian medical personnel were regarded as combatants and withdrew from the battlefield, leaving the wounded to die on the field.

- The Austrians were compelled to redeploy one of their three army corps from Italy to Vienna. The remaining Austrian forces in the theatre concentrated their defences around Trentino and Isonzo.

- On 5 July, the Italian government received news of a mediation effort by the French emperor Napoleon III for a settlement of the situation, which would allow Austria to receive favourable conditions from Prussia, and, in particular, to maintain Venetia.

- The situation was embarrassing for Italy, as its forces had been beaten back in the only battle to date. As the Austrians were redeploying more and more troops to Vienna to defend it against the Prussians, La Marmora was urged to take advantage of the numerical superiority of his army, score a victory, and thus improve the situation for Italy at the bargaining table.

- In a council of war that met on 14 July in Ferrara, the new Italian war plans were agreed upon:

- Cialdini was to lead the main army of 150,000 troops through the Venetia, while La Marmora, with roughly 70,000 men, would detain the Austrian forces in the Quadrilatero.

- The Italian navy under Admiral Carlo di Persano was to set sail from Ancona with the objective of taking over Trieste.

- Garibaldi and his army of volunteers, known as the Hunters of the Alps, reinforced by a division of regular infantry, were to advance into Trentino, with the objective of capturing the province’s capital, Trento.

- Cialdini successfully crossed the Po River on 8 July, advancing to Udine on 22 July without running into the Austrian forces. Meanwhile, Garibaldi succeeded in winning the Battle of Bezzecca on 21 July, clearing the pathway for the invasion of Trentino.

- However, both their successes were overshadowed by the unexpected defeat of the Italian navy at the Battle of Lissa on 20 July at the island of Vis, off the coast of Dalmatia. Persano’s forces were beaten back and subsequently defeated by the Austrian fleet on the island.

- On 26 July, a mixed Italian force of bersaglieri and cavalry defeated an Austrian force guarding the crossing of the Torre River at the Battle of Versa. It marked the maximum Italian advance into Friuli.

- The Prussians broke the terms of their Prussian-Italian alliance and signed a peace treaty with the Austrians. The Italians feared that the Austrians looked ready to send reinforcements and continue the fight. Yet this was not the case. Unwilling to risk a defeat, the Italians were compelled to come to the peace table. On 9 August, Garibaldi was ordered in a telegraph by the Army High Command to vacate Trentino. His response, which later became famous in Italy, was simply “Obbedisco” meaning “I shall obey”.

Aftermath of the war

- Pressured by France and Prussia, Italy settled an agreement with Austria. The cessation of hostilities between the two was agreed to at the Armistice of Cormons signed on 12 August.

- The Peace of Prague signed on 23 August stipulated the awarding of the Iron Crown of Lombardy to Victor Emmanuel II, the King of Italy, and the Austrian cession of Venetia.

- However, Austria refused to surrender Venetia directly to Italy as the Italian army had not defeated the Austrian army.

- The Italian government felt humiliated that it was not involved in the Austro-Prussian peace talks, and that Italy was to receive Venetia as a gift from France.

- The Italian government thus demanded it would only annex Venetia after a plebiscite, in order for it to appear as the will of the people rather than a French gift.

- The Peace of Prague was followed up by the Austrian-Italian Treaty of Vienna on 3 October, which confirmed the cession of the territory to Italy, however without Trentino.

- The plebiscite was held on 21 and 22 October, and the result was overwhelmingly in support of joining Italy.

- During this period, an uprising also occurred in Sicily, called The Seven and a Half Days Revolt.

- By the end of the war, Italy’s desire for unification had been emboldened, making the Third War for Independence another crucial step on the path to full national unity. Due to the Prusso-Italian alliance, not just Italy secured its future unification, but Prussia had also cleared a path towards German unification.

Image sources: