Download The Vichy Regime Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach The Vichy Regime to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Table of Contents

Add a header to begin generating the table of contents

Summary

- The factors behind the inauguration of Vichy France.

- The changes that occurred under the Vichy France regime headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain.

- The events leading up to the end of Vichy France.

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about the Vichy Regime!

- The Vichy government was the French fascist government that collaborated with the Germans in the creation of racist policies. Inaugurated on 22 June 1940 and ended in September 1944, the government was led by Marshal Pétain.

Overview

- There are a number of common themes between authoritarian regimes and the Vichy Regime: the cult of the leader, police repression, the redefining of notions of justice, the rejection of liberal democracy, hostility towards both capitalism and socialism, and the theme of national regeneration.

- On 22 June 1940, the Third Republic (founded in 1870) collapsed, and Marshal Pétain declared the start of a new era for France: the État Français was proclaimed.

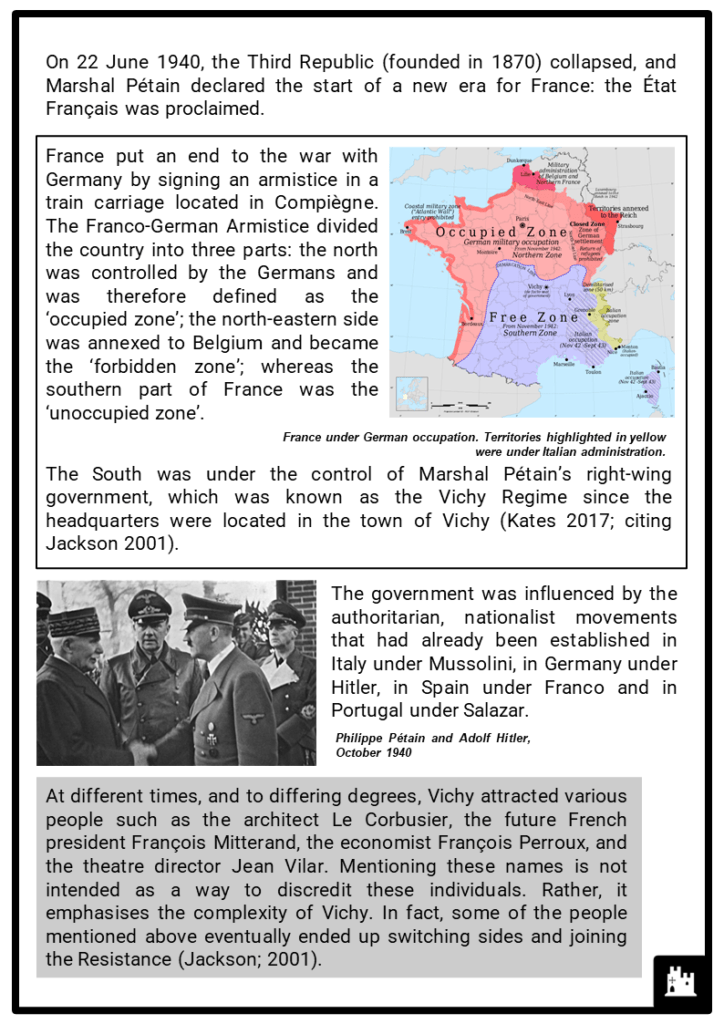

- France put an end to the war with Germany by signing an armistice in a train carriage located in Compiègne. The Franco-German Armistice divided the country into three parts: the north was controlled by the Germans and was therefore defined as the ‘occupied zone’; the north-eastern side was annexed to Belgium and became the ‘forbidden zone’; whereas the southern part of France was the ‘unoccupied zone’.

- The South was under the control of Marshal Pétain’s right-wing government, which was known as the Vichy Regime since the headquarters were located in the town of Vichy (Kates 2017; citing Jackson 2001).

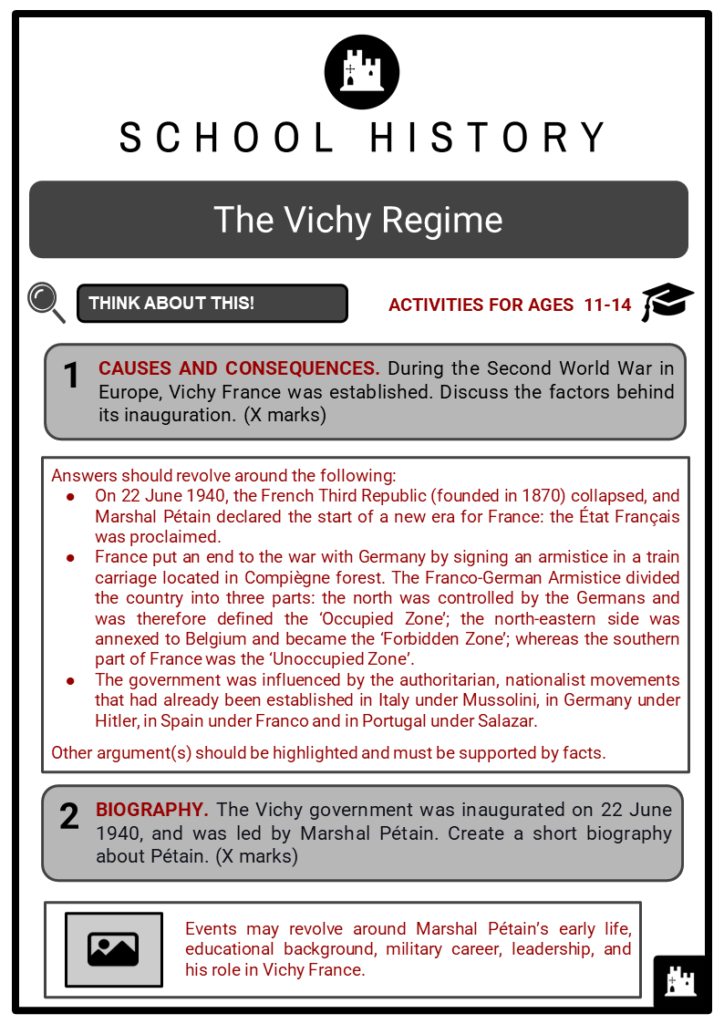

- The government was influenced by the authoritarian, nationalist movements that had already been established in Italy under Mussolini, in Germany under Hitler, in Spain under Franco and in Portugal under Salazar.

- At different times, and to differing degrees, Vichy attracted various people such as the architect Le Corbusier, the future French president François Mitterand, the economist François Perroux, and the theatre director Jean Vilar. Mentioning these names is not intended as a way to discredit these individuals. Rather, it emphasises the complexity of Vichy. In fact, some of the people mentioned above eventually ended up switching sides and joining the Resistance (Jackson; 2001).

Making a Myth out of France’s defeat

- The traditionalist right of Vichy was convinced that the French defeat in the war was divine punishment for years of easy living and decadence: years in which the notion of rights had been placed before duties, where the people had lost the fundamental French values and been unwilling to sacrifice themselves.

- For these reasons, Vichy clearly found religion a useful message to promote, because inherent in the Christian religion was the principle that out of suffering could come greatness. Just as Christ’s sufferings had been salutatory, so the French suffering following defeat could allow the country to regenerate and reconnect with its national purpose (Kitson; no date).

- Moreover, Pétain believed France’s low birth rate played a central role in her defeat: ‘Trop peu d’enfants, trop peu d’armes, trop peu d’alliés, voilà les causes de notre défaite’ (‘Not enough children, not enough weapons, not enough allies, this is why we were defeated’) (Kitson; 2001).

- According to Pétain’s correct family order, fathers had absolute authority over wives and children, and woman’s legal and civil rights were restricted by legislation. The Vichy Regime wanted to bring France back to its old glory by advocating a return to the soil, to the ‘true’ values that France had forgotten with time.

- According to Vichy, France once again had to become an agricultural peasant’s country: ‘retournez à la terre’ (‘return to the soil’) was to be a policy, not a mere literary slogan. The government sought to promote rural values and peasant culture: popular traditions and folklore were encouraged; the earth was to be considered as a solace, a fatherland, in which French people had to be rooted and with which they had to re-establish contact as it was the essence of eternal France.

- ‘For Vichy, the myth of craftsmen and peasants imbued with proper values of life and behaviour existing in an idyllic image of rural areas, prevailed over the reality of an industrial and commercial urban society’ (Curtis; 2002: 95).

- Vichy refused to recognise that rural life had changed: peasants had become more prosperous, more bourgeois; they no longer coincided with the regime’s image (Curtis; 2002: 95). For this reason, Vichy encouraged outdoor life through youth camps in the countryside (Kitson; no date). The new desirable society required a new kind of youth and youth culture.

French Reforms

- According to Marshal Pétain, a good government had to be supported by a strong state; and in La Nouvelliste de Lyon – an old-established Royalist organ – he declared his intentions to build a new state ‘on the ruins of the monstrous and flabby State which collapsed under the weight of its weaknesses and mistakes far more than under the blows of the enemy’.

- The German presence was oppressive. For instance, Alsace-Lorraine underwent total Germanisation: subsequently, school lessons were conducted in German; Nazi organisations like the Hitler Youth were introduced; statues of Joan of Arc were pulled down, and berets were forbidden.

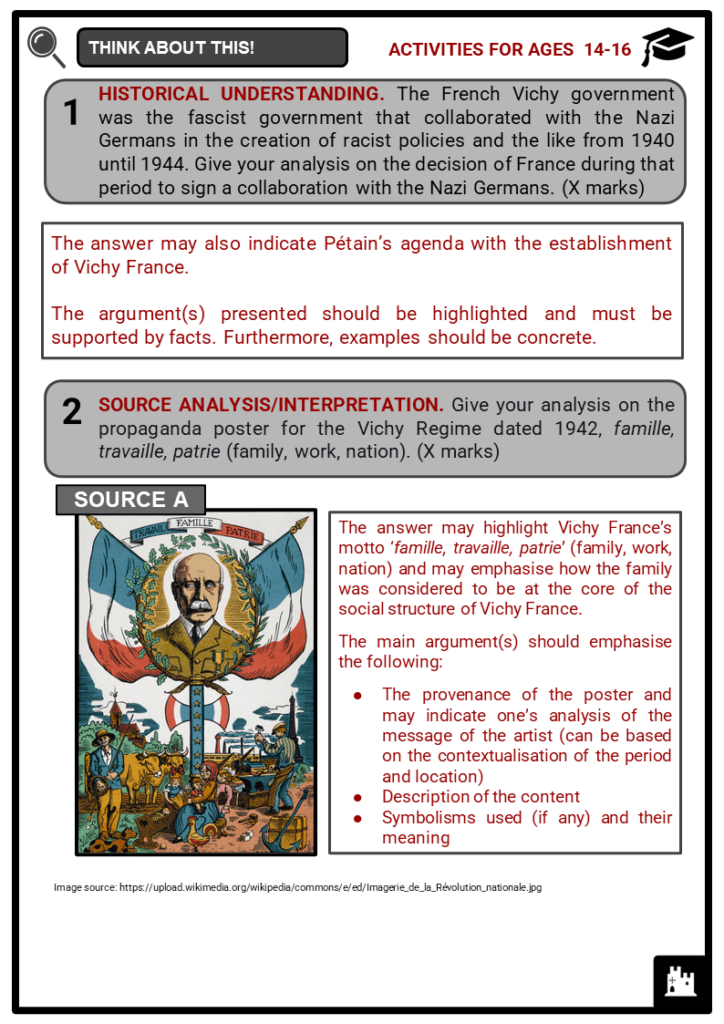

- It was against this background of fragmentation that Vichy set about implementing its National Revolution (Jackson; 2001). In fact, its regime sought to implement three main values: ‘Christianity, family, and work’ (Kates 2017). During the years of the regime, France’s motto changed from ‘liberté, égalité, fraternité’ (freedom, equality, fraternity) to ‘famille, travaille, patrie’ (family, work, nation) (Kates 2017).

- Moreover, throughout Pétain’s government, the family was considered to be at the core of social structure: ‘In the new order which we are setting up,’ he claims, ‘the family will be honoured, protected, aided’ (Vaucher; 2000).

Youth

- Youth also played a fundamental role in the creation of the new regime. However, Vichy did not set up a single youth body along the lines of the Hitler Youth or the Italian GIL (Italian Youth of the Lictor).

- In addition to a Ministry of Youth, Family and Sport, it created over sixty organisations that were engaged in training the young in the right values of discipline, courage, loyalty and practical ability. This would be done by changing the school system, and by offering ‘healthy collective experiences’ in organised groups (Curtis; 2002).

- The government’s youth initiatives that sought to combat unemployment and dislocation tended to be the most successful. In fact, such initiatives assigned community work to groups of young people in order to engage them in activities, such as helping those in need, or collaborating with harvesting. These organisations gave basic training for the unemployed between the ages of 14 and 21. Youth groups were heavily imbued with the moralism of patriotic duty and civic service, yet, promised camaraderie and joy (Lackerstein; 2012: 193).

- Young men could learn a trade or spend six months in the countryside learning peasant skills. On the contrary, young women had more restricted choices: in the urban and rural centres they were taught ‘feminine skills’ such as cooking, laundry, sewing and baby care; and although they were promised eventual employment, there was never any doubt that their ultimate training was to become wives and mothers. (Lackerstein; 2012:193).

Work

- Pétain expressed the necessity of reorganising the French people’s work life by assigning them specific roles within society. He carried out such an objective by introducing the Charte du Travail (the Labor Charter) in October 1941.

- In essence, Pétain intended to create a system that guided (or controlled) people in the choice of their work options: ‘when our young men and our young women enter life […] we shall tell them that it is fine to be free; but that real ‘Liberty’ can be attained only in the shelter of a protective authority which they must respect and obey. […] we shall recognise their right to work – not, however, at any occupation they may choose, for in this domain freedom of choice will be limited within the possibilities of the economic situation and the demands of the national interest’ (Foreign Affairs, 2013; Anonymous, 1941).

- As the ‘father of the nation’, Pétain’s role was to transcend social divisions and to appeal directly to the French population, a feature he had achieved with considerable success in the early years of the regime. This autocratic style of government aimed to convince people that hierarchy, order and self-sacrifice were the remedy to all of France’s ills and would regenerate the nation (Gorrara and Langford; 2003). Moreover, Vichy’s ministers generally shared a philosophy that people should know their place in society and should not seek equality with their hierarchical superiors. (Kitson; no date). For these reasons, police forces became stricter: with the new law of 23 April 1942, all police personnel were to become agents of the new state (Curtis; 2012: 90).

- The French police during the Second World War were used both as (I) a tool of collaboration – between the Vichy Regime and the Nazi occupier – and (II) to enforce an internal political reform: Vichy’s National Revolution. Police actions included the handing over of communists and Jews to the Nazis.

- Pétain had some clear ideas of how France ought to be, and he wanted to build ‘[a] true France, the real France, not the France of Jews, not the France of grèves—no strikes, strikes [were] illegal. Not the France of working-class organisations, no CGT, organised workers need not apply, need not exist, et cetera’ (Kates 2017; Merriman 2007, 47-50).

The Role of Women in Vichy France

- The government’s official propaganda preferred to portray women allegorically, as ‘Marianne’ and ‘Victory’, or as nurses, wives and mothers (Jackson; 2001). In fact, Vichy legislation encouraged women to stay at home and breed, and much greater emphasis was placed on Mothers’ Day celebrations. In essence, women were encouraged to do their ‘duty’ as mothers, repopulating France (Gorrora and Langford; 2003). Large families would be given certain privileges and family allowances (Curtis; 2002: 95).

- Divorce was made impossible during the first three years of marriage and the regime introduced draconian laws (such as the one in September 1941 that made abortion a capital offence, punishable by death) (Gorrora and Langford; 2003). In fact, due to the aforementioned law, two women were executed (one of them was Marie-Louise Giraud, guillotined in 1943) (Kitson; no date).

- Moreover, a Vichy law of 1940 restricted the ability of women to work in the civil service and denied them further promotion to senior positions. By 1942, about 14% of women in senior posts had been dismissed. However, the 1940 law soon had to be suspended: irrespective of the pious rhetoric about the family, Vichy was faced with the reality that the number of single women had sharply increased because of the absence of prisoners of war and the men who worked in Germany.

- Vichy had wanted to restrict the employment of women, yet female labour was needed by 1942. At first, women were involved in charity networks and in assisting prisoners of war.

- By 1942, almost a quarter of all French workers in Germany were women; by 1944 about 50,000 women worked there (Curtis; 2002: 95).

The End of the Vichy Regime

- Pétain’s regime came to an end in September 1944, concomitantly with the end of the Second World War, and Charles de Gaulle’s liberation of Paris.

- Overall, Pétain’s government was responsible for many cruelties, including the deportation of not only 76,000 Jews, but also that of people who were not considered suited to be French, for instance, Gypsies and homosexuals.

- Following their defeat, the Germans were expelled from France, and whoever had collaborated with the Nazis was ‘prosecuted and punished for their crimes against the French nation’ (Simonovski 2017).

- According to The Guardian, Marshal Pétain and his wife left Vichy in the early morning, leaving a ‘farewell message to the French people, apologising for the past four years and giving veiled encouragement to follow De Gaulle’ (no date).

Image sources:

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/90/Le_cartouche_de_l%27État_Français.svg/800px-Le_cartouche_de_l%27État_Français.svg.png

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/64/Bundesarchiv_Bild_183-H25217%2C_Henry_Philippe_Petain_und_Adolf_Hitler.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/90/Bundesarchiv_Bild_146-1971-041-10%2C_Paris%2C_der_Kollaboration_beschuldigte_Französinnen.jpg