Revolutions of 1830 Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the Revolutions of 1830 to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Resource Examples

Click any of the example images below to view a larger version.

Fact File

Student Activities

Summary

- Charles X

- July Revolutions

- Other Revolutions of 1830

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about the Revolutions of 1830!

The Revolutions of 1830 were a series of widespread uprisings that occurred throughout Europe in the year 1830. The period witnessed two "romantic nationalist" uprisings, namely the Belgian Revolution in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands and the July Revolution in France. Additionally, there were rebellions in Congress Poland, various Italian states, Portugal, and Switzerland. The Revolutions of 1830 were an extensive crisis that spanned throughout the entire Europe, encompassing various types of political reform and outright revolt.

CHARLES X

- Charles X of France took a far more conservative line than his brother Louis XVIII. Charles X attempted to rule as an absolute monarch and reassert the authority of the Catholic Church in France. He was crowned in 1824 when the Ultra-royalist party wanted a return to the aristocracy and absolutist politics.

- King Charles was anointed at the Cathedral of Reims on 29 May 1825. This cathedral is traditionally where French kings are consecrated. However, it had not been used for this purpose since 1775 because Louis XVIII chose to avoid controversy by not having the ceremony. Napoleon consecrated his revolutionary kingdom in the venerable cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris.

- However, when Charles ascended the throne of his forefathers, he chose to be crowned in the traditional location used by the kings of France since the early days of the monarchy. Although Charles’ brother had the clarity of mind to understand that France would never approve of an effort to revive the Ancient Régime, Charles was unwilling to embrace the transformations that had occurred in the previous forty years.

- Charles experienced a reaction. Acts of desecration in churches were subject to capital punishment, and the freedom of the press was significantly curtailed. Ultimately, he endeavoured to provide restitution to the families of the aristocrats whose assets were demolished in the course of the Revolution. After ruling for a few years, France grew discontent among its people due to an economic decline, opposition to the restoration of conservative policies, and the emergence of a liberal media. The lack of popularity of Charles as a ruler became evident in April 1827, when disorder broke out during the King’s inspection of the National Guard in Paris.

- Amidst the decline of the French economy, a succession of elections resulted in the emergence of a comparatively influential liberal coalition in the Chamber of Deputies. The increase in the liberal faction within the Chamber of Deputies was almost parallel to the emergence of liberal media in France. It became progressively significant in communicating political viewpoints and the political state to the Parisian population. It may, therefore, be regarded as a vital connection between the emergence of the liberals and the increasingly restless and economically distressed French people.

- The liberals, known as “Les doctrinaires,” supported the monarchy and advocated for a constitutional monarchy. Marquis de Lafayette was their leader. This was a conflict on the suitable extent of royal authority. In response to the issue, the King sought to implement new legislation regarding press censorship as a means to suppress the escalating wave of vehement criticism directed towards the government and the church.

- The implementation of stringent high stamp duty on printed material in January 1828 resulted in the downfall of Prime Minister Joseph de Villèle. The idea was withdrawn due to the strong objections of the parliamentarians, which left the administration feeling humiliated. Villéle tendered his resignation, and the monarch appointed a more moderate minister, Jean-Baptiste de Martignac, as his replacement.

- Martignac was promptly rejected because of opposition from both left-wing and right-wing extremists. The King himself disapproved of his policies. Jules de Polignac took his place. Upon the Chamber’s reconvening on 2 March 1830, numerous deputies disapproved of Charles’ reign. An individual proposed legislation mandating that the minister of the King must secure the endorsement of the Chambers.

- On 18 March 1830, the majority of the members of the Chamber voted in favour of the proposed legislation. As a result, Charles suspended the Chamber the following day. The general elections held in June did not result in the desired majority for the government of the King. In the face of increasing resistance, Charles utilises the authority granted by Article 14 of the 1814 Charter, which grants him extraordinary powers during times of crisis and temporarily suspends the constitution.

- At the outset, few of Charles’ critics imagined it possible to overthrow the regime; they hoped merely to get rid of Polignac. As for Charles, he ignored the idea of serious problems; he did not overthrow the spirit of the French. He was aware that the citizens of Paris had revolted but saw it as a temporary outburst of French temperament.

- The recent capture of Algiers, Algeria's capital, reinforced Charles’ confidence. In order to enhance his authority, he chose to issue the July Ordinances co, commonly known as the Four Ordinances of Saint-Cloud, on 26 July. These decrees curtail the freedom of the press, dissolve the bicameral parliament, limit the number of eligible voters, and establish a specific date for upcoming elections, thus consolidating authority in the monarchy. The Ordinances:

- Suspended the liberty of the press

- Appointed new councillors of State

- Dissolved the Chamber of Deputies of France

- Reduced the number of deputies in the Chamber that will be created in the future

- Convened additional electoral bodies during the month of September in that particular year

- Revoked the Deputies’ privilege to make amendments.

- Disenfranchised the commercial middle class in the next elections

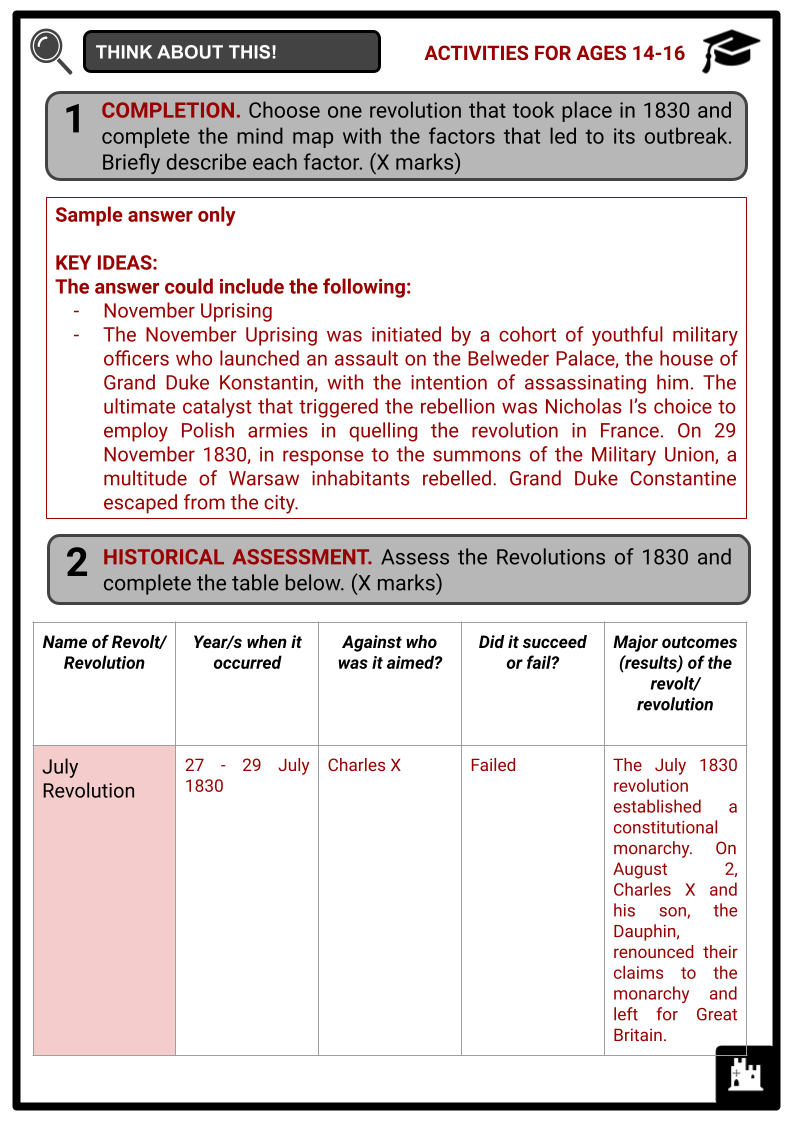

JULY REVOLUTION

- There was a prevailing sentiment of protest against the absolute monarchy. As a reaction, Louis Philippe, Duke of Orléans, attempted to contain the situation, but this only worsened the issue as silenced parliamentarians and numerous working men from Paris flooded the streets and constructed barricades during the “three glorious days” of 27-29 July 1830.

Monday, 26 July 1830

- The Revolution commenced on 27 July 1830. More than 50 newspapers are declining to comply with the new regulations and are now publishing provocative content against the King. The police endeavoured to confiscate the printing machines but were assaulted by a ferocious crowd. Shortly after the first altercations, barricades were promptly erected. Contrary to expectations, the Parisians took up the role of aggressors by hurling paving stones, roof tiles, and flower pots from the higher floors of buildings.

- Initially, the soldiers discharged cautionary rounds into the atmosphere. However, by the end of the night, a total of twenty-one individuals had lost their lives. One of the dead bodies was dragged around the city to incite further outrage. The Revolution started. Fighting in Paris continued throughout the night.

Tuesday, 27 July 1830, Day One

- As the day progressed, Paris became increasingly silent while the bustling crowds continued to grow in size. At 4:30 pm, the commanders of the troops belonging to the First Military Division of Paris and the Garde Royale received orders to gather their forces and artillery at the Place du Carrousel, strategically positioned to face the Tuileries, the Place Vendôme, and the Place de la Bastille. Military patrols were developed, reinforced, and extended throughout the city to uphold order and safeguard gun dealers from looters. Nevertheless, no specific precautions were implemented to safeguard the weapon stockpiles or gunpowder facilities. Initially, the preparations appeared to be unnecessary, but at 7:00 pm, the conflict commenced.

Wednesday, 28 July 1830, Day Two

- To suppress the uprising, the King sent General Auguste de Marmont to Paris. Marmont is at a significant disadvantage in terms of numbers, as most of his soldiers were dispatched to conquer Algiers. The French troops are ineffective, as revolutionaries assail them with gunfire and swiftly vanish. They hoist the tricolour flag and sound the bell of Paris. Nevertheless, the King and his Prime Minister Polignac adamantly decline to meet with anyone. A cohort of liberals in Paris drafted a petition demanding the withdrawal of the regulations. The monarch responded that he would engage in negotiations only if the rebels surrendered their guns; nonetheless, the King was aware that he had no intention of revoking the ordinances. He failed to comprehend the actual importance of the movement at that time.

Thursday, 29 July 1830, Day Three

- By the third day, the rebels had achieved a high level of organisation and possessed significant weaponry. Within 24 hours, more than 4,000 barricades were hastily erected across the city. Marmont is not receiving any instructions or additional troops. The banner of the revolutionaries, known as the tricolore or the “people’s flag,” was seen flying over a growing number of significant structures. The Tuileries Palace was looted by 1:30 pm. The Hôtel de Ville, the most valuable prize, was captured by mid-afternoon. The liberals established a temporary government and assigned Lafayette the task of pacifying the unruly crowds to prevent a situation similar to the one that occurred in 1792. There was apprehension that the revolutionaries would succeed in establishing a new republic.

- Initially, the soldiers discharged cautionary rounds into the atmosphere. However, by the end of the night, a total of twenty-one individuals had lost their lives. One of the dead bodies was dragged around the city to incite further outrage. The Revolution started. Fighting in Paris continued throughout the night.

OTHER REVOLUTIONS OF 1830

- The July Revolution signified the change from one form of government, the Bourbon Restoration, to another, the July Monarchy. It involved the transfer of power from the main branch of the Bourbon family to its secondary branch, the House of Orléans. Additionally, it resulted in substituting the concept of inherited rights with the idea of popular sovereignty. The abdication of Charles signifies the conclusion of the Bourbon monarchy in France. For nearly 250 years, a dynasty had ruled, except for the Revolution and Bonaparte, starting from Henry IV. After the July Revolution, several revolutions happened in Europe.

Belgian Revolution

- In late August 1830, a revolt against Dutch authorities erupted in the streets of Brussels, shortly after the July Revolution had caused the downfall of the Bourbon dynasty in France and the establishment of a more progressive government led by the House of Orléans, a branch of the Bourbon family. The Brussels uprising resulted in the loss of government authority over the city. It extended to other significant towns in the Belgian provinces of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, particularly in the French-speaking south, but not exclusively.

- Regardless of the specific factors that led to the violent outburst in late August and the individuals responsible for instigating it, the opposition union that had been established in Belgium between 1827 and 1828 promptly and effectively took control of the Revolution. The opposition union comprised Catholics and liberals advocating for increased parliamentary oversight, expanded suffrage, and robust guarantees of freedom of the press, religion, and education. Conservative Catholics have now adopted the last two arguments, with the endorsement of the Church, as a way to resist King William I’s meddling in the Church, religion, and education.

- The Dutch army’s intervention in Brussels, which ultimately failed, led to the escalation of the Brussels uprising and spurred a Belgian movement for independence. The declaration of independence for the Belgian provinces of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands took place on 4 October 1830. A temporary governing body had been established, and it was decided to convene a National Congress to create a constitution for the newly constituted nation.

November Uprising

- The November Uprising, alternatively referred to as the Polish–Russian War 1830–31 or the Cadet Revolution, was a military insurrection in the central region of partitioned Poland, aiming to oppose the Russian Empire. The rebellion commenced on 29 November 1830 in Warsaw, initiated by youthful Polish officers hailing from the military academy of the Army of Congress Poland under the leadership of Lieutenant Piotr Wysocki.

- The rebellion quickly attracted significant portions of Lithuania, Belarus, and Right-bank Ukraine populations. Despite the insurgents’ modest victories, the insurrection was ultimately quashed by a larger Imperial Russian Army led by Ivan Paskevich. In 1832, the Russian Emperor Nicholas I enacted the Organic Statute, which resulted in the loss of autonomy for Russian-occupied Poland and its integration into the Russian Empire. Warsaw was reduced to primarily a military garrison, resulting in the closure of its university.

Frequently Asked Questions

- What were the Revolutions of 1830?

The Revolutions of 1830, also known as the July Revolutions, were a wave of revolts across Europe against conservative governments. These uprisings were primarily influenced by liberalism and nationalism, seeking to overthrow old monarchies and establish more democratic governments.

- Where did the Revolutions of 1830 take place?

The most notable uprisings occurred in France, Belgium, Poland, and various parts of Italy and Germany.

- What caused the Revolutions of 1830?

The causes were multifaceted and included economic hardship, political repression, and the spread of liberal and nationalist ideas. The French Revolution of 1830, for example, was sparked by King Charles X's unpopular policies and the July Ordinances, which restricted the press and dissolved the Chamber of Deputies.