Athelstan Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Athelstan to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Ascension to Throne and Capture of York

- Reign

- Law Code

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about Athelstan!

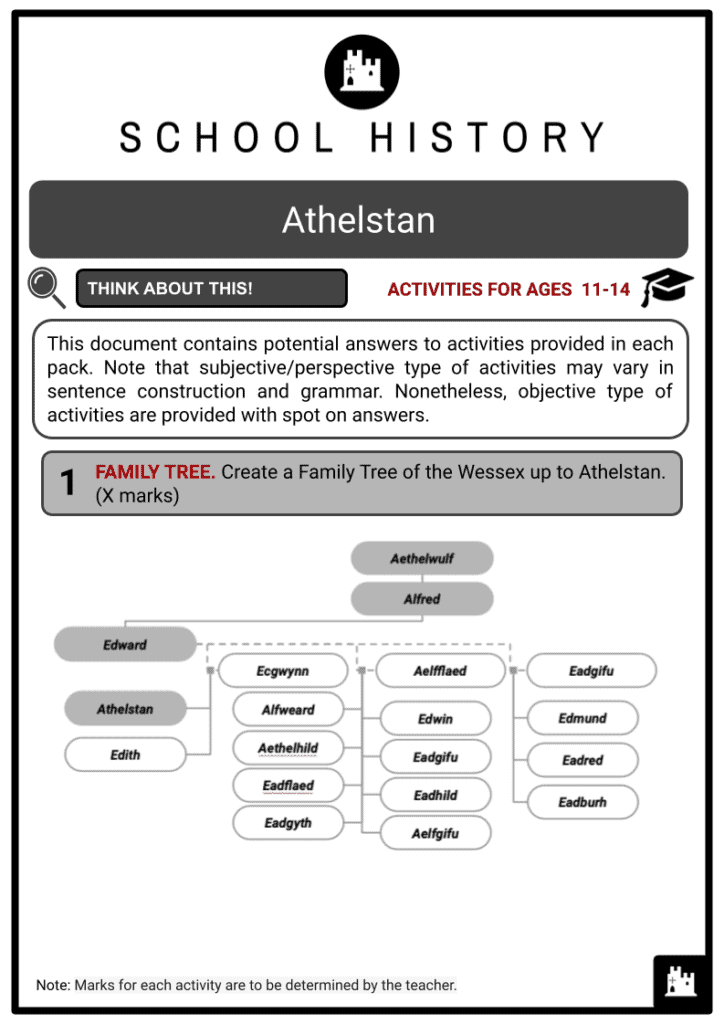

Athelstan, or Æthelstan, ruled the Anglo-Saxons from 924 to 927 and the English from 927 until his passing in 939. He was the son of Ecgwynn, the first wife of King Edward the Elder. He is regarded as one of the "greatest Anglo-Saxon rulers" and the first King of England by contemporary historians. His half-brother Edmund I succeeded him; he never wed and had no children. When he passed away in 939, the Vikings retook York, and it wasn't until 954 that they were eventually able to retake all of England.

ASCENSION TO THRONE AND CAPTURE OF YORK

- The death of Edward the Elder in 924 was not immediately followed by the coronation of his eldest son, Athelstan. Having been brought up by Aethelred and Aethelflaed, Athelstan was meant to rule over Mercia and his half-brother, Alfweard, was to take their ancestral kingdom of Wessex.

- Alfweard died not long after Edward the Elder, which led to Athelstan taking over and being anointed in 925 as king over all the territories previously ruled by their father. Several months prior to his coronation, he encountered resistance from members of the Wessex nobility. However, this failed to break off his accession.

- Much of northern Danelaw had surrendered to the rule of Edward the Elder. The area above Humber, which included Scotland, Strathclyde and the important trading centre of York, was still controlled by numerous northern kings. With the support of the Mercians, Athelstan hammered out a deal with the northerners.

- Athelstan arranged the marriage of his sister, Edith, to Raegnald’s successor, Sihtric of York, in 926. The agreement took place at Tamworth, Staffordshire. Through the device of marriage, Athelstan extended the Anglo-Saxon territory and authority. However, this agreement was thrown to the wind when Sihtric died. Sihtric’s son from an earlier marriage, Olaf, became the king of York and was given a protector: his uncle, Guthfrith, the king of the Vikings from Ireland. Athelstan perceived this as a threat and acted correspondingly.

- Athelstan then stormed York. He ordered the destruction of the fortifications in York to drive out Guthfrith’s forces.

- This would prevent York from being a base for further opposition. It proved Athelstan’s eagerness to use his military skills and resources to defend his authority.

- It demonstrated Athelstan’s assertion to gain the recognition of the Welsh, Scottish and Northumbrians of his leadership of Wessex and Mercia. More importantly, the capture of York in 927 gave way to Athelstan’s claim that he had control over all Anglo-Saxon armies, which meant that he held authority over the whole of England.

- After subduing the Viking northerners in 927, Athelstan preemptively raided the Scottish settlements in the north using land and sea routes in 934. In response to this harrying, the rulers of the Scots and Strathclyde in the far north, Constantine and Owain, forged an alliance with the king of Dublin, Olaf Guthfrithsson. This culminated in the Battle of Brunanburh in 937.

- The combined armies of Constantine, Owain and Olaf marched south into England.

- Both sides suffered heavy casualties. Several prominent members of both armies were killed.

- Athelstan gathered and prepared his West Saxon and Mercian armies for the invasion.

- The well-equipped military force of Athelstan emerged victorious in the battle.

- The defeat of the alliance of Constantine, Owain and Olaf Guthfrithsson at Brunanburh was recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. With the united kingdom of Wessex and Mercia, the Anglo-Saxon armies had sealed victory. Athelstan secured the northern borders of England and contained the threat to his rule. Northumbria failed to fully integrate into England: several factions in the north attempted to preserve their autonomy. Trouble from the Scottish and their allies did not necessarily end.

Depiction of the Battle of Brunanburh

ASCENSION TO THRONE AND CAPTURE OF YORK

- Whilst the Viking threat appeared to have been controlled by Athelstan’s actions early in his reign, it was continuously dealt with using a variety of methods.

- Athelstan set up the marriage of his sister to Sihtric of York and successfully formed an alliance with the northern Vikings. Both parties agreed not to invade each other’s territory and not to support the enemies of the other.

- Olaf succeeded his father, Sihtric, as king of York whilst his uncle, Guthfrith, acted as his protector. Guthfrith refused to continue the previous agreement between Sihtric and Athelstan. This led to Athelstan’s capture of York in 927. Olaf fled to Ireland whilst Guthfrith sought protection in Strathclyde. Athelstan demanded the kings of Scotland and Strathclyde acknowledge his overlordship. Consequently, the king of Scotland consented to the baptism of his son with Athelstan as godfather. Guthfrith attempted to besiege York but failed; he surrendered to Athelstan before returning to Ireland.

- Olaf Guthfrithsson, the son of Guthfrith, made an alliance with Constantine and Owain to invade Athelstan’s territory. Their combined armies were defeated at the Battle of Brunanburh by Athelstan’s well-managed military force. The immediate threat of Guthfrithsson was successfully controlled.

- Harald Fairhair, the first king of Norway, accepted Athelstan as his overlord. He sent his son, Haakon, to the Anglo-Saxon court. Athelstan acted as Haakon’s foster father and brought him up as a Christian.

- The previous arrangements between Athelstan’s immediate predecessors and prominent people in the continent proved beneficial to the European relations of Anglo-Saxon England during Athelstan’s rule. By Athelstan’s time, the connection was well-established and a considerable degree of mutual respect and understanding was shared between his court and its foreign counterparts. In fact, Athelstan was crowned with the Carolingian ceremony to draw a comparison between his rule and the Carolingian tradition.

- Arrangements initiated by previous rulers included:

- Marriage of Aethelwulf to Judith, daughter of the king of West Francia Charles the Bald

- Marriage of Alfred the Great's daughter Ælfthryth to Judith's son by a later marriage, Baldwin II, Count of Flanders

- Marriage of Athelstan's half-sister, Eadgifu, to Charles the Simple, king of the West Franks

- The Royal Court of Athelstan moved from one location to another, but was generally held in the south. Changes in the king’s court included:

- A royal chancery was solely assigned in drawing up of charters. Charters during his reign appeared uniform in nature.

- A significant number of royal feasts, including festival days of Christmas, Easter and Whitsun, were held during his rule.

- Ealdormen were associated with the king through blood ties or marriage and were bound to the king through homage and fealty. The most senior magnates were ealdormen. They met with the king by way of council at various venues. Reforms in the role of the ealdormen included:

- Mercia was divided into two: the west and the east.

- The west, which came to be known as Mercia, consisted of Lichfield, Worcester and Hereford, while the east, known as East Anglia, included Lincoln to Thames, Cambridge and Northampton.

- One ealdorman was assigned to each division.

- This indicated that ealdormen were given wider authority since only a few were appointed.

- As a consequence of the alterations to the role of the ealdormen and partition of Mercia, administrative units such as shires, hundreds and burhs were given significant duties.

- SHIRES

- Reeves became increasingly important in shire management.

- Shires were divided into hundreds.

- Each shire had a burh.

- HUNDREDS

- A hundred was the division of a shire for administrative, military and judicial purposes under the common law.

- Each hundred had a court, which met every four weeks and was attended by 'all the chief men'.

- Hundreds were also used for recruiting troops.

- BURHS

- Whilst burhs continued to be used for defence and administration of localities, they were regarded primarily as ports or trading centres.

- This was reinforced by designating coin minting and trading of all goods worth up to 20 pennies in burhs.

LAW CODES

- Previous Anglo-Saxon kings produced law codes to meet changing circumstances. Athelstan’s grandfather, Alfred the Great, was known for the creation of the Doom Book. Like his predecessors, Athelstan introduced a new law code that was to act as a point of reference for both the law enforcers and those who might commit an offence.

- Athelstan ordered the laws to be written in the vernacular which allowed the local officials to:

- Interpret and implement them efficiently,

- Show a distinct line of communication between the king and his subjects,

- Demonstrate a willingness to negotiate over judicial matters,

- Create a sense of shared values,

- Resolve problems related to internal disagreement.

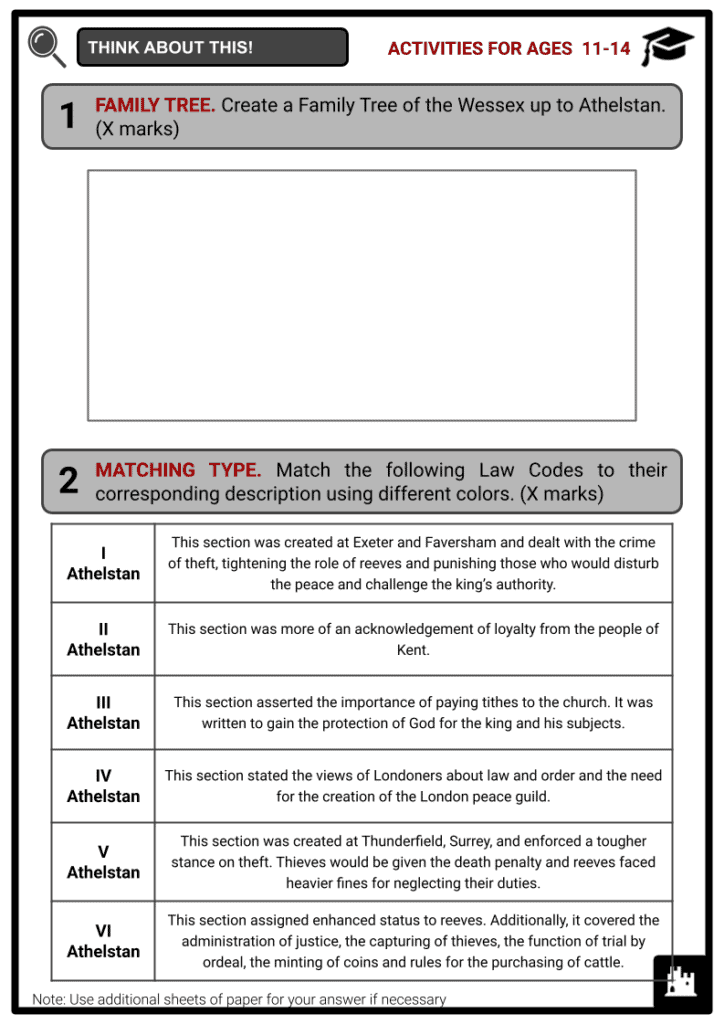

- Athelstan’s law code was divided into sections, which were produced at different points in time. The chronological order of the code was I, II, V, IV, III and VI.

- I Athelstan. This section asserted the importance of paying tithes to the church. It was written to gain the protection of God for the king and his subjects.

- II Athelstan. This section assigned enhanced status to reeves. Additionally, it covered the administration of justice, the capturing of thieves, the function of trial by ordeal, the minting of coins and rules for the purchasing of cattle.

- V Athelstan. This section was created at Exeter and Faversham and dealt with the crime of theft, tightening the role of reeves and punishing those who would disturb the peace and challenge the king’s authority.

- IV Athelstan. This section was created at Thunderfield, Surrey, and enforced a tougher stance on theft. Thieves would be given the death penalty and reeves faced heavier fines for neglecting their duties.

- III Athelstan. This section was more of an acknowledgement of loyalty from the people of Kent.

- VI Athelstan. This section stated the views of Londoners about law and order and the need for the creation of the London peace guild.