Download the Byzantine Empire Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach the Byzantine Empire to your students?

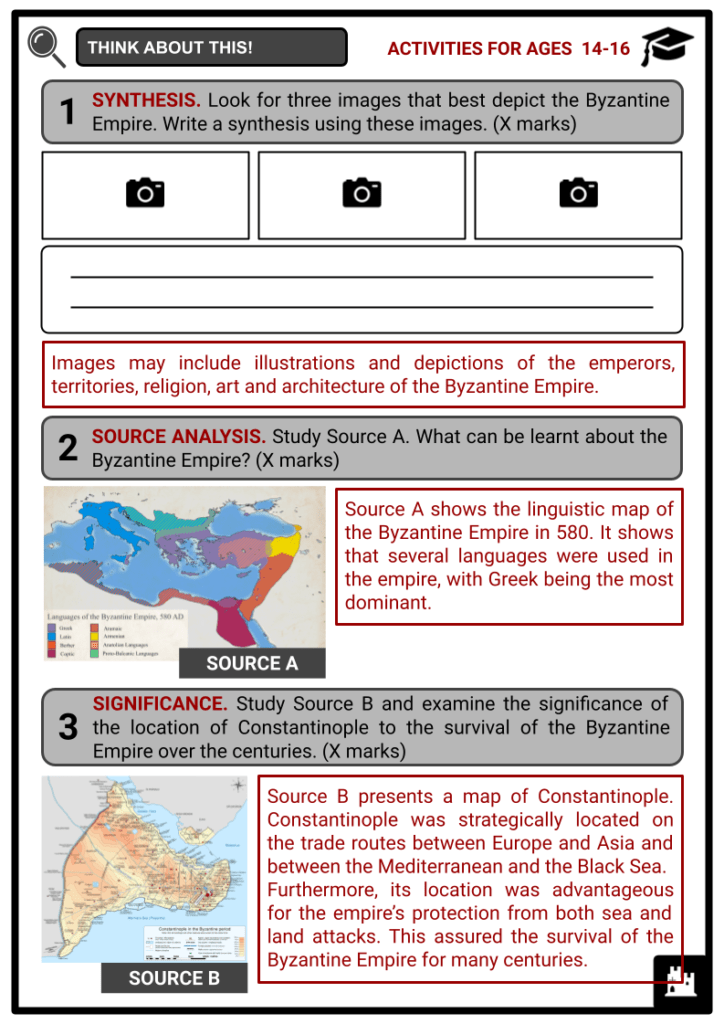

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Table of Contents

Add a header to begin generating the table of contents

Summary

- Origins of the empire

- The flourishing of the empire

- Challenges to the empire and the Byzantine Renaissance

- The decline of the empire and the fall of Constantinople

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about the Byzantine Empire!

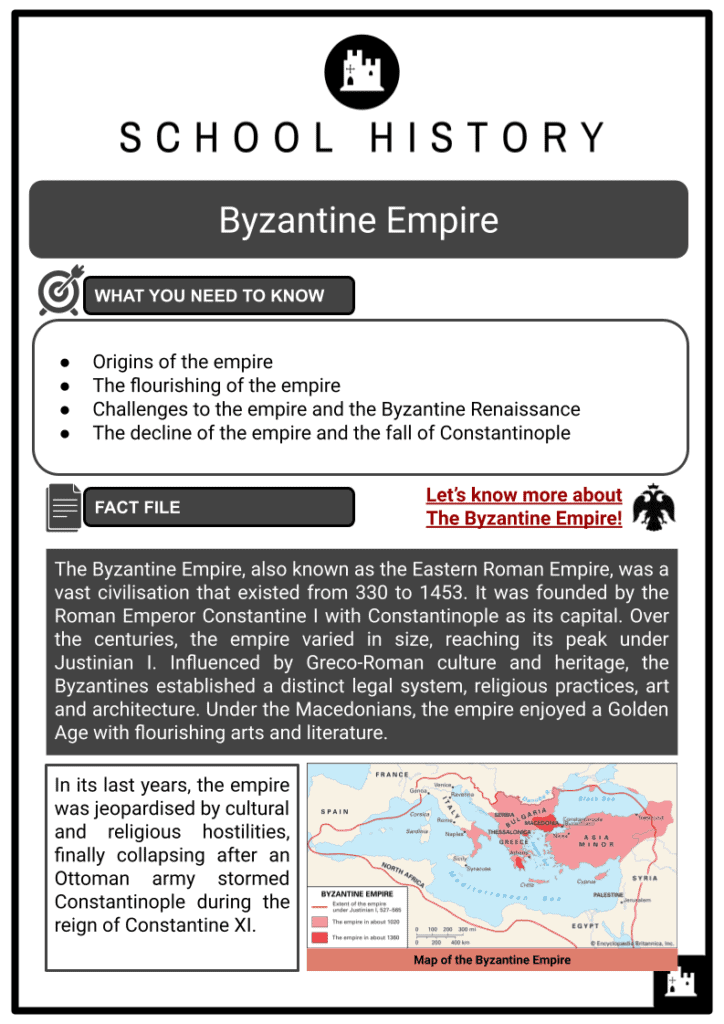

- The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was a vast civilisation that existed from 330 to 1453. It was founded by the Roman Emperor Constantine I with Constantinople as its capital. Over the centuries, the empire varied in size, reaching its peak under Justinian I. Influenced by Greco-Roman culture and heritage, the Byzantines established a distinct legal system, religious practices, art and architecture. Under the Macedonians, the empire enjoyed a Golden Age with flourishing arts and literature.

- In its last years, the empire was jeopardised by cultural and religious hostilities, finally collapsing after an Ottoman army stormed Constantinople during the reign of Constantine XI.

Origins of the empire

- The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or simply Byzantium, was the continuation of the eastern half of the Roman Empire after the western half collapsed and dissolved into various feudal kingdoms. It was named after Byzantium, the name given to the city of Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul).

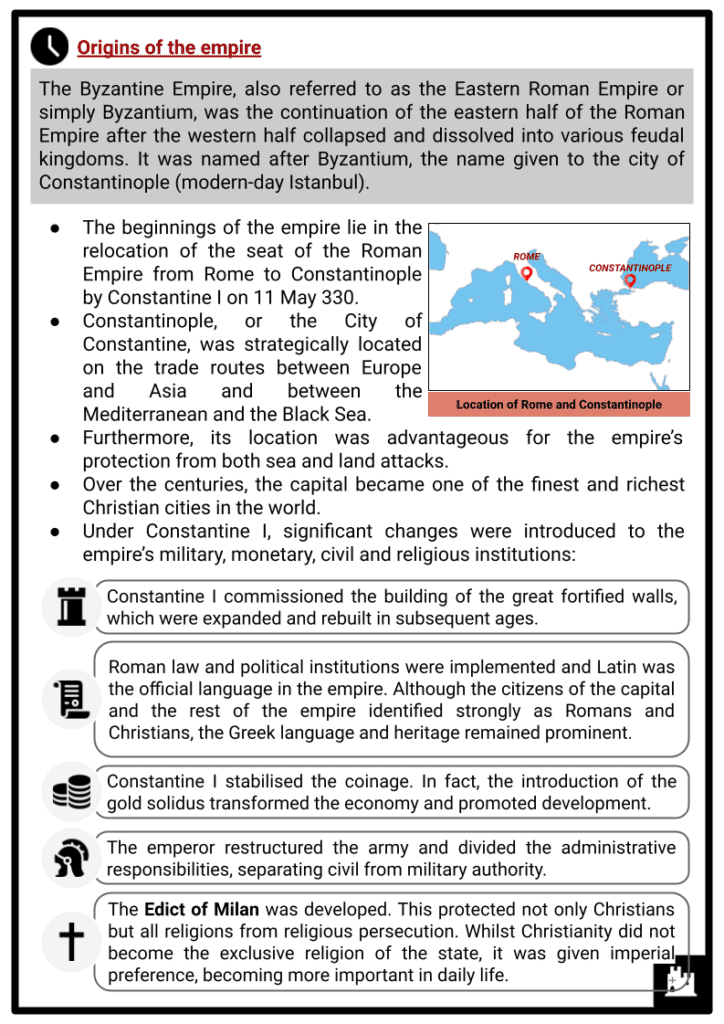

- The beginnings of the empire lie in the relocation of the seat of the Roman Empire from Rome to Constantinople by Constantine I on 11 May 330.

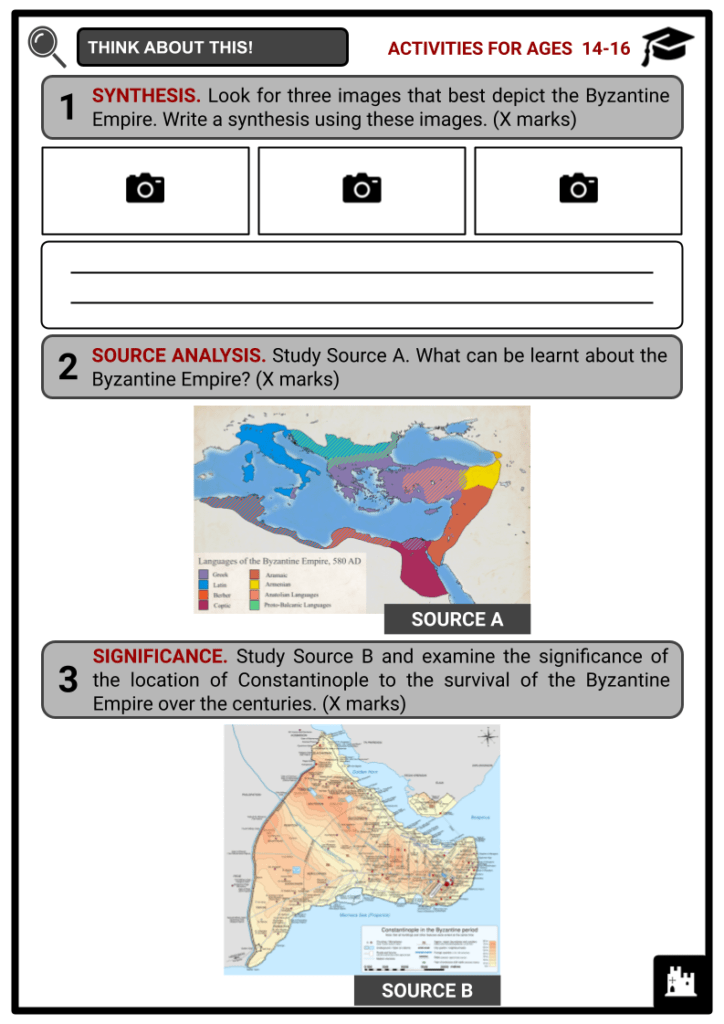

- Constantinople, or the City of Constantine, was strategically located on the trade routes between Europe and Asia and between the Mediterranean and the Black Sea.

- Furthermore, its location was advantageous for the empire’s protection from both sea and land attacks.

- Over the centuries, the capital became one of the finest and richest Christian cities in the world.

- Under Constantine I, significant changes were introduced to the empire’s military, monetary, civil and religious institutions:

- Constantine I commissioned the building of the great fortified walls, which were expanded and rebuilt in subsequent ages.

- Roman law and political institutions were implemented and Latin was the official language in the empire. Although the citizens of the capital and the rest of the empire identified strongly as Romans and Christians, the Greek language and heritage remained prominent.

- Constantine I stabilised the coinage. In fact, the introduction of the gold solidus transformed the economy and promoted development.

- The emperor restructured the army and divided the administrative responsibilities, separating civil from military authority.

- The Edict of Milan was developed. This protected not only Christians but all religions from religious persecution. Whilst Christianity did not become the exclusive religion of the state, it was given imperial preference, becoming more important in daily life.

- As a result, the empire recovered much of its military strength and enjoyed a period of stability and prosperity.

- The rule of Constantine I until 337 created a precedent for the position of the emperor as possessing great influence and decisive governing authority within the religious discussions involving the early Christian councils of that time.

- Whilst the Roman Empire was unified under Constantine I, it was later divided into western and eastern sections. The two sections had varying fates over the next centuries. The western region was constantly attacked by Germanic invaders, breaking the empire down until Italy remained the only territory left under Roman control. By 476, Rome had fallen, and the Byzantine Empire remained the only Roman Empire left standing.

The flourishing of the empire

- Owing to its geographic location and internal political stability, the Byzantine Empire was able to survive for centuries after the fall of Rome. Its established urban culture and greater financial resources allowed it to pacify invaders with tribute and pay foreign mercenaries. The fortified walls of Constantinople made the city impermeable to most attacks until the 13th century.

- In the sixth century, the Byzantine Empire flourished under the rule of Justinian I.

- Coming to the throne in 527, Justinian I dreamt of retaking the lands of the lost West Roman Empire and ruling a single, united Roman Empire from Constantinople.

- With his competent army, he reclaimed the former province of Africa from the Vandals and Italy from the Ostrogoths.

- Under Justinian I, the Byzantine Empire is believed to have reached its peak in terms of territorial expansion.

- Apart from territorial expansion, Justinian I established several reforms and projects:

- The magnificent domed Church of Holy Wisdom, or Hagia Sophia, was built, along with many great monuments and public works projects including bridge and roads.

- Roman law was codified, which came to be known as Corpus Juris Civilis, creating a Byzantine legal code that would last for centuries and help shape the modern concept of the state.

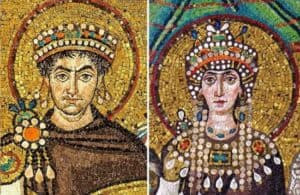

- Justinian I encouraged the arts including music, drama and art.

- With the involvement and leadership of Theodora, the wife of Justinian I, the rights of women were upheld and laws were passed that prohibited forced prostitution and closed brothels.

- Justinian I attempted to impose religious unity by forcing doctrinal compromises that might appeal to all parties, which displeased many people.

- Whilst the emperor’s conquests gave power and prestige to the empire, they came at a huge cost. Debts were incurred, leaving resources drained. Furthermore, the plague wiped out huge numbers of the empire’s population, stopping the empire’s period of prosperity.

Challenges to the empire and the Byzantine Renaissance

- The succeeding emperors were forced to rely on heavy taxation in order to maintain the Byzantine Empire. Moreover, the imperial army found it difficult to keep the territory conquered under Justinian I.

- In the seventh and eighth centuries, the vast empire was exposed to attacks from the Persian Empire and the Slavs.

- Following the foundation of Islam, Muslim armies began their assault on the empire by storming into Syria.

- By the end of the century, several lands were lost to the Islamic forces including Syria, the Holy Land, Egypt and North Africa among other territories.

- From 730 until the early ninth century, Byzantine emperors spearheaded a movement that eliminated the veneration of icons.

- Whilst a reaction against image venerating, doctrines and practices may be found in earlier centuries, fully fledged Iconoclasm, or destruction of images, emerged as an imperial policy only under Leo III. The movement rose and fell under various rulers, ending definitively in 843 when a Church council under Michael III ruled in favour of the display of religious images.

- During the late 10th and early 11th centuries, the Byzantine Empire enjoyed a Golden Age under the rule of the Macedonian dynasty.

- Whilst it stretched over less territory, it successfully dealt with its rivals. Despite the wars, prosperity was realised.

- Trade was more controlled, and greater wealth and prestige were achieved.

- The Macedonian era, sometimes called the Byzantine Renaissance, is considered one of the best periods of the empire:

- The imperial government patronised Byzantine art and literature including mosaics.

- Complex techniques from ancient Greek and Roman art mixed with Christian themes were developed by the artists of the time.

- Churches, palaces and other cultural institutions were restored

- Political and religious expansion were undertaken. Crete, Cyprus and most of Syria were conquered. The Bulgarians, Serbs and Rus converted to Orthodox Christianity.

- Greek became the official language of the state, and a thriving culture of monasticism was centred on Mount Athos in north-eastern Greece.

- The great rulers of the Golden Age moulded the history of that age.

The decline of the empire and the fall of Constantinople

- After a long period of secure prosperity, the Byzantine Empire was aggravated by a conflict between the military aristocracy of the provinces and the bureaucracy of Constantinople. At the same time, its new enemies were gathering their strength, appearing almost simultaneously on the northern, eastern and western frontiers.

- In the 11th century, the Pechenegs, a Turkic tribe, began raiding the empire in the north.

- On the eastern frontier, the Seljuk Turks, who were inspired by the Muslim idea of jihad or holy war, conquered several territories including Nicaea, the heart of the empire’s military and economic strength.

- On the western frontier, the Normans pursued their conquest of Italy.

- The final loss of Italy seemed to highlight the East-West Schism, or the formal declaration of institutional separation between the east into the Orthodox Church, now Eastern Orthodox Church, and the west into the Catholic Church, now Roman Catholic Church.

- The separation involved the splitting of the churches along doctrinal, theological, linguistic, political and geographical lines.

- With its boundaries shrunk, the empire was reduced to a small Greek state fighting for survival that now depended on the new political, commercial and ecclesiastical forces in the West.

- With the empire gaining Western support against the Seljuk Turks, Pope Urban II declared a holy war at Clermont, France in 1095.

- This marked the beginning of the First Crusade.

- The Crusades were a series of holy wars waged by European Christians against Muslims in the Near East from 1095 to 1291.

- With the help of the crusaders from France, Germany and Italy, Nicaea was recaptured from the Muslims.

- Alexius I, the emperor at the time, took advantage of the First Crusade to maximise the benefits for the empire.

- Hostility continued to build between the Byzantine Empire and the West in the succeeding Crusades, concluding in the conquest and looting of Constantinople by the West during the Fourth Crusade in 1204.

- This resulted in irreparable damage to the city and immense harm to the East-West understanding.

- The Latin regime established in Constantinople was constantly threatened by the Byzantine rulers of northern Greece while in the centre and south of the country its conquests were more lasting.

- Many refugees from Constantinople fled to Nicaea, where a microcosm of the Byzantine Empire and church in exile were built.

- This Byzantine government-in-exile retook the capital and overthrew Latin rule in 1261. However, the crippled economy of the empire never regained its former stature.

- In 1369, under the weak rule of John V, Byzantium became a vassal state of the Turks.

- As a vassal state, it paid tribute to the sultan and provided him with military assistance.

- The empire gained a brief period of relief from Ottoman oppression under John V’s successors.

- However, the rise of Murad II as the Ottoman Sultan in 1421 marked the end of the final respite.

- Murad II withdrew all privileges given to the Byzantines and laid siege to Constantinople.

- The siege was completed by his successor, Mehmed II, who victoriously entered the Hagia Sophia on 29 May 1453.

- With the fall of Constantinople under Constantine XI came the end of a glorious era for the Byzantine Empire, ushering in the long reign of the Ottoman Empire.