Celts Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the Celts to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Origin of the Celts

- Celtic Culture

- Warfare and Decline

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about the Celts!

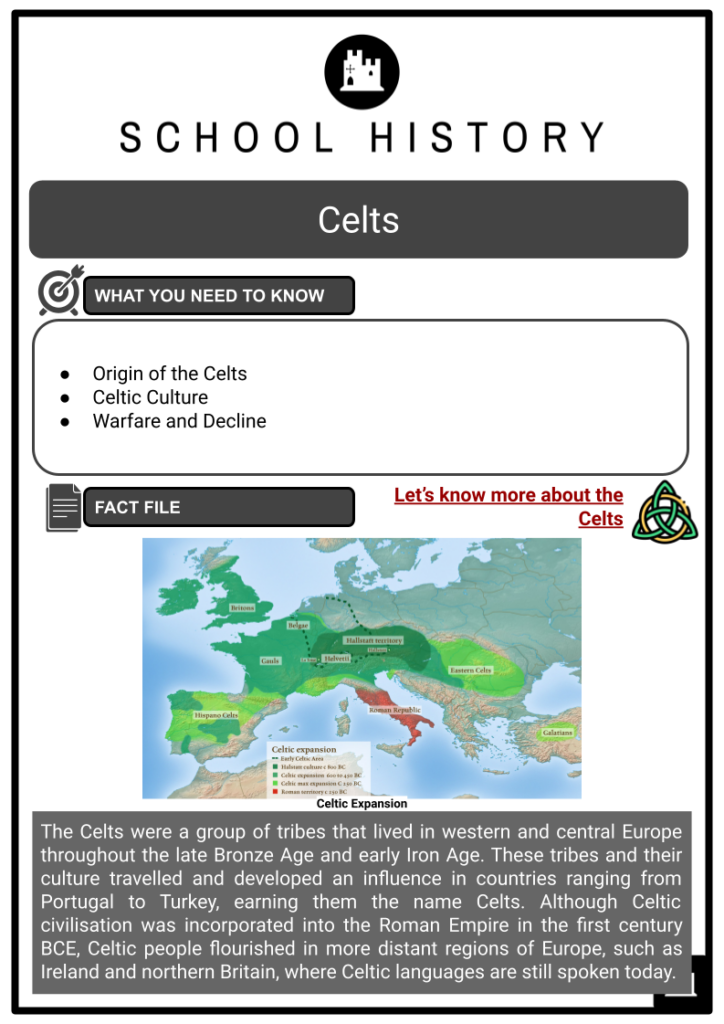

The Celts were a group of tribes that lived in western and central Europe throughout the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age. These tribes and their culture travelled and developed an influence in countries ranging from Portugal to Turkey, earning them the name Celts. Although Celtic civilisation was incorporated into the Roman Empire in the first century BCE, Celtic people flourished in more distant regions of Europe, such as Ireland and northern Britain, where Celtic languages are still spoken today.

ORIGIN OF THE CELTS

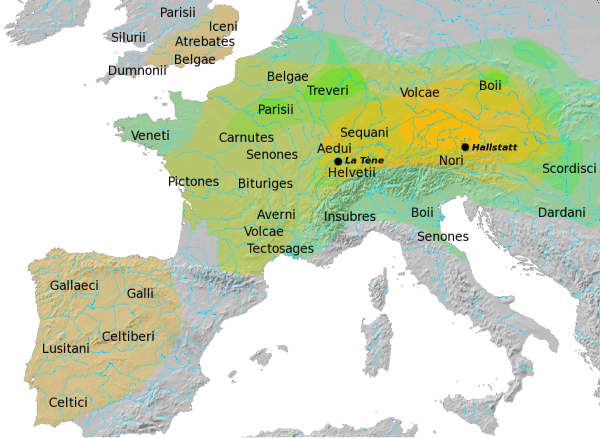

- The origins of Celtic culture may be traced back to three earlier, closely related and overlapping cultural groups, according to most scholars. The first is the Urnfield civilisation of the late Bronze Age, which flourished along the upper Danube from about 1300 BCE. The common practice of interring the cremated bones of the deceased in urns and burying them gave this civilisation its name. Due to a lack of archaeological evidence, these individuals remain unknown. Ironworking technology extended over Europe from the beginning of the first millennium BCE to the next two or three centuries. As a result, iron overtook bronze as the preferred metal for crafting stronger and more durable equipment and weapons.

- The Hallstatt culture was the second proto-Celtic group, named after the Hallstatt site in Upper Austria, which lived from 1200 BCE to 450 BCE.

- It peaked between the eighth and sixth centuries BCE. In one direction, the Hallstatt culture extended to western Austria, southern Germany, Switzerland and eastern France, and in the other, eastern Austria, Bohemia and portions of the Balkans.

- The ancient Celts emerged from the western part of this region. Trade, tribal affiliations, intermarriages, imitation and migration were all potential ways for the Hallstatt civilisation to expand.

- Local reserves of salt, iron and copper, which could be exchanged along waterways, helped these people develop.

- The presence of imported products in Hallstatt burial mounds, as well as costly commodities such as gold and amber jewellery, demonstrates that commerce stretched as far south as Mediterranean societies (the Etruscans in Italy and the Greek colonies in southern France).

- The Hallstatt civilisation began to fade in the 5th century BCE, owing to a lack of local resources, greater tribal rivalry, and a shift in trading routes.

- The La Tène culture (c. 450 – c. 50 BCE), named after a place on the northern banks of Lake Neuchâtel in Switzerland, is the third key group in the establishment of Celtic civilisation.

- The La Tène civilisation was eventually present in a large arc spanning western and central Europe, ranging from Ireland to Romania, and was best defined as a group of disparate tribes connected by shared elements in art and religion.

- Ironworking, making votive offerings in water sources, leaving weapons in graves, and painting with swirling, geometrical and vegetal designs are all cultural elements.

- There is a huge amount of evidence indicating commerce with the Mediterranean states once again. Around key river sites like the Loire, Marne, Moselle and Elbe, La Tène centres were particularly effective.

- Because it existed in non-Celtic locations, such as Germanic-speaking Denmark, the La Tène culture does not closely correlate to the Celtic people. Nonetheless, the word ‘La Tène’, which was developed by archaeologists to categorise objects, is still widely (though imprecisely) used to describe Celtic culture in Europe throughout the second millennium BCE.

CELTIC CULTURE

- The common language of numerous Iron Age European people is one of the most prominent indicators of connection. The Indo-European language family includes the Celtic language. Insular Celtic and Continental Celtic are the two categories of Celtic languages identified by scholars. After the Roman imperial period, the latter group was no longer extensively spoken, and the only surviving evidence are references in the works of Greek and Roman writers, as well as a few brief epigraphic relics such as ceramic graffiti and votive and burial stelae. Gaulish is the best documented of this group.

- There are two types of Insular Celtic languages: British or Brittonic (Breton, Cornish and Welsh) and Goidelic (Irish and its medieval derivatives, Scots Gaelic and Manx). During the Roman era, Brittonic was spoken throughout Britain. Cumbrian (extinct since medieval times), Cornish (no longer spoken after the 18th century CE but lately resurrected), Breton (possibly brought by 5th-century CE British invaders but not directly related to Gaulish) and Welsh were all descended from it. The first evidence of Goidelic-Irish originates from the 5th century CE, following which it developed into Middle Irish (c. 950-1200 CE) and then Modern Irish, which is still spoken today.

- The religion of the Celtic people is known as polytheistic religion with many gods, though we only know about them through classical authors due to the lack of documented works by the Celts themselves. Variations occurred throughout locations and centuries, but the following were common aspects of ancient Celtic religion:

- reverence for sacred trees as well as other natural sites such as rivers and springs.

- food, weapons, animal and (rarely) human sacrifices are all examples of votive offerings to gods.

- the practice of putting valuable and common items in tombs with the departed, showing a belief in an afterlife.

- a belief in the protective power of totem animals, especially stags and boars.

- a reverence for the human head, which was thought to be where the soul resides.

- taboos were used to guarantee that religious and communal rules were followed.

- druids led the festivities.

- There are no surviving sacred writings, songs or prayers for the Celtic religion since druids were reluctant to commit their wisdom to writing. Cernunnos, ‘the horned god’, who most likely symbolised nature and fertility, was granted all-encompassing abilities or traits. Another important character is Lugus (later known as Lugh), the sun god who was considered as all-knowing and all-seeing and was arguably the only universally worshiped god in the Celtic culture.

- It is hard to reconstruct the dynamics of ancient Celtic civilisation without first-hand written documents. Nonetheless, we know that many Celtic tribes had hierarchical societies. The monarchs and elite soldiers were at the top, followed by the druids, who were free from taxation and military duty and were religious leaders and custodians of the community’s collected knowledge. Then there were skilled craftworkers, traders, slaves and farmers – by far the largest group in rural and agrarian communities.

- Celtic societies were headed by monarchs at first, then by elected chiefs or a small council of elders. Many tribes eventually banded together for mutual help or were reliant on another, more powerful tribe, and so paid a tribute. By the end of the period, huge confederations of tribes had formed to combat the shared Roman threat.

- Cartimandua, ruler of the Brigantes tribe in the north of England in the mid-1st century CE, and Boudicca (d. 61 CE), queen of the Iceni tribe, who led a revolt of many tribes against the Roman occupation in 60 BCE, are two examples of women who were leaders in Celtic Britain. There is also evidence that certain women were treated equally to males when it came to burial with treasure, such as the Vix burial at Châtillon-sur-Seine in northeast France in the 6th-5th century BCE.

Hallstatt (yellow) and La Tène (green) Cultures - There was a strong kinship structure in place, with rulers and their extended families dominating society through land ownership and trade earnings. Gift-giving, hosting Celtic feasts, and social display were all used by rulers to keep their subjects loyal. Fostering children with other aristocratic families strengthened family ties, a strategy that was also used to link various tribes together in alliances. There was also a system, similar to feudalism in the Middle Ages, in which the elite bore responsibility for the welfare and protection of those who provided some type of service in exchange.

- Except for slaves, there is no indication that a child of one of the social groups could not later join another if they gained the required wealth (for example, by war valour) or completed the necessary education or apprenticeship, which for a druid lasted about 20 years. In his Gallic Wars, Julius Caesar (c. 100-44 BCE) stated that Celtic women in Gaul brought a dowry to their spouses, which could be inherited by the lady if her partner died before her. Husbands possessed the power of life and death over their wives and children, according to Caesar. Scholars disagree whether this was valid and if it applied to Celts elsewhere.

WARFARE AND DECLINE

- The abundance of gods involved with warfare in the ancient Celtic pantheon, as well as the large quantity of weapons found in tombs, show that warfare was an important component of Celtic civilisation. On the battlefield, bravery and prowess were also essential indicators of social position. In Gaul, Celtic warriors bleached their long hair with lime water, whereas in Britain they painted patterns on their bodies. Several classical authors also remarked how strange it was for Celtic warriors to fight naked and gather the heads of their foes. A torc necklace was worn by many Celtic warriors, and it was most likely a symbol of prestige and rank. Celtic women are known to have fought.

- Spears, long swords, and unique large rectangular or oval shields were utilised by Celtic soldiers. Slingers, chariots and cavalry were used by Celtic armies, while standards and war horns were used to keep the battlefield orderly. From the 4th century BCE onwards, Celtic armies caused chaos for their neighbours as tribes travelled west, south and east in waves in search of new wealth prospects in what is known as the Celtic Migration.

Brennus - Brennus, the head of the Gallic Senones tribe, famously attacked Rome in 390 BCE, and the Celts wreaked havoc again in 279 BCE when they destroyed Delphi on their route to Asia, where they became known as the Galatians. In 225 BCE, the Celtic tribes attacked the Romans again, and throughout the Punic Wars, they were regular mercenary allies of Carthage (264-146 BCE).

- However, in large-scale wars, Celtic armies were no match for more disciplined and better-equipped foes like the Hellenistic kingdoms and the Romans. Once conquered, however, Celtic soldiers, who had long been known for their courage, went on to fight as mercenaries in various Greek and Roman armies.

- The construction of oppida in the 2nd and 1st centuries BCE was the first major indicator of turmoil in the Celtic world, as local rivalry for resources and trade possibilities increased dramatically. An oppidum was the Roman term for bigger communities, which we today use to refer to fortified structures that are typically found on high points in the landscape or on plains at naturally defensible areas such as river bends. The fortifications were typically made out of an earthworks circuit wall with outer ditches. Oppida were used as a safe place during wartime and as a location to concentrate industrial workshops and keep the community’s resources.

- This hostile environment worsened when the Romans sought vengeance for the damage caused by migrating Celtic tribes in the previous two centuries, and were tempted into ultimate conquest by the promise of gold and other riches. The Romans invaded the Arverni tribe in Gaul in 125 BCE, and Julius Caesar attacked and conquered Gaul less than a century later, despite heavy resistance from tribal leaders like Vercingetorix (82-46 BCE).

- As the Roman Empire grew, direct attacks on significant communal figures like the druids became more common, and the Celts on the continent and in southern Britain were finally incorporated into Roman society.

- The Celts thrived in more remote areas such as Ireland and northern Britain. Celtic culture would persist in these places throughout the medieval era, showing itself most dramatically in epic poetry of Irish, Welsh and Scottish medieval literature and in Christianised art.

- These epic poems, as well as elaborate curvilinear designs within illuminated manuscripts, widespread penannular brooches, and sophisticated vegetal motifs on towering stone crosses in churchyards carried on the old Celtic traditions.