Charlemagne Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Charlemagne to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Early Life

- King of Franks and Lombards

- Holy Roman Emperor

- Death and Legacy

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about Charlemagne!

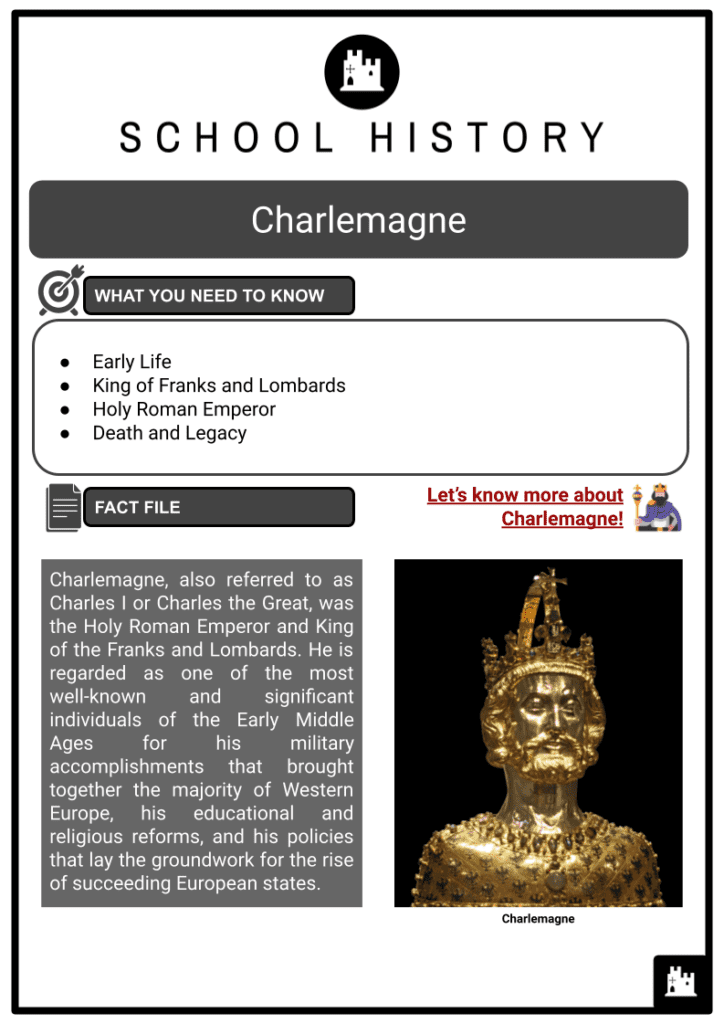

Charlemagne, also referred to as Charles I or Charles the Great, was the Holy Roman Emperor and King of the Franks and Lombards. He is regarded as one of the most well-known and significant individuals of the Early Middle Ages for his military accomplishments that brought together the majority of Western Europe, his educational and religious reforms, and his policies that lay the groundwork for the rise of succeeding European states.

EARLY LIFE

- The Merovingian Dynasty, which had dominated the area from around 450, was in its declining years when Charlemagne was likely born at Aachen (in modern-day Germany). Years had passed during which the Merovingian monarch had been slowly losing power and prestige, while the presumably inferior royal position of Mayor of the Palace (similar to a Prime Minister) had increased in authority. By the reign of King Childeric III, the king had almost no authority, and Pepin the Short, Mayor of the Palace, made all administrative policy decisions.

- His father, Pepin, realised he couldn't just grab the position and expect to be accepted as the rightful ruler.

- The hostile Lombards in Northern Italy and the iconoclasm dispute with the Byzantine Empire were only two of the issues the Pope was facing at this time.

- Recently, the Byzantine Emperor had declared all depictions of Christ in churches to be idolatry and commanded their removal.

- Additionally, he had attempted to impose this similar strategy for the pope and to have it adopted throughout Western Europe.

- When Pepin was proclaimed King of the Franks in 751, he chose his two sons to succeed him in accordance with royal tradition.

- Following the death of King Pepin in 768, his sons took over the kingdom.

- Co-rule with Carloman was far from peaceful since Charlemagne preferred taking immediate action to solve problems.

- Their reign was first put to the test in 769 when Pepin's conquered region of Aquitaine rebelled. Carloman opposed a military effort, whereas Charlemagne did not.

- Carloman declined to take part in any of it when Charlemagne invaded Aquitaine, crushed the rebels, and also conquered nearby Gascony. In 770, Charlemagne married a Lombard princess — the daughter of the monarch Desiderius — whom he later divorced in order to wed Hildegard, who was still a teenager (future mother of Louis the Pious). The two brothers were headed straight into civil war until Carloman passed away in 771 as a result of Desiderius's pleadings with Carloman to overthrow Charlemagne and restore the honour of his daughter.

KING OF FRANKS AND LOMBARDS

- Charlemagne established himself as the single ruler of the Franks through the sheer power of his personality, which personified the warrior-king attitude along with a Christian worldview. He began the deadly and lengthy Saxon Wars in 772 after assembling his army and launching his first invasion into Saxony in an effort to exterminate Norse paganism in the area and establish his dominance there. He travelled to Italy, where the Lombards were once more establishing themselves, after leaving forces in Saxony. In 774, he overthrew the Lombards and annexed their domains, establishing himself as King of the Franks and Lombards, before returning to Saxony.

Charlemagne in the Saxon Wars - A series of battles, notably the infamous Battle of Roncevaux Pass in 778, in which Charlemagne's rearguard was ambushed and slaughtered, including the count Roland of the Breton March, was sparked by Basque discontent in the Pyrenees. Nothing but Charlemagne's will to fully dominate the area was strengthened by this setback.

- Charlemagne waged annual campaigns in the Pyrenees, Spain, and Germania between 778 and 796, triumphing again and again. He agreed to the Hungarian Avars' surrender in 795, but because he didn't trust them, he attacked their fortress and destroyed them in 796, putting an end to their existence as a nation. Additionally, he had seized Corsica and vanquished the northern Spanish Saracens, creating the Spanish March as a security perimeter. With the exception of Saxony in the north, his realm now encompassed what is now northern Spain, northern Italy, and modern-day France.

- The Saxons rebelled once Charlemagne felt he had defeated them and put an end to their conflict.

- The territory of Saxony had been friendly with Francia before the Saxon Wars and frequently engaged with them, acting as a trading route to Scandinavian nations.

- According to legend, a Saxon group invaded and burned a church in Deventer (in what is now the Netherlands) in 772, giving Charlemagne the justification he needed to conquer the area.

- It is unclear why the Saxons would have destroyed the Deventer church, let alone if they actually did.

- It is possible that the Christian monarch was behind the church's demolition to provide justification for an invasion of the Germanic tribe he would have conducted anyhow given Charlemagne's contempt for pagan beliefs and customs.

- In retaliation for the burned-out church, Charlemagne invaded Westphalia, destroyed the sacred tree known as the Irminsul, which symbolised Yggdrasil (the Tree of Life in Norse mythology), and massacred some Saxons during his initial expedition. His second, third and the remaining victims (a total of 18) all committed the same acts of murder and devastation.

- A Saxon warrior-chief by the name of Widukind commanded the resistance in 777, but despite his skill as a commander, he was powerless to truly oppose Charlemagne's military apparatus. However, he managed to persuade King Sigfried of Denmark to let Saxon refugees into his realm.

- In an attempt to shatter the Saxons' resolve to resist, Charlemagne ordered the killing of 4,500 people in the Massacre of Verden in 782. Despite this tragedy, the Saxons still refused to cede their independence or renounce their religion. After making a gesture of goodwill by offering himself for baptism, it is noted that Widukind was baptised, yet he quickly vanishes from the annals of history.

- The refugee train to Denmark was stopped by Charlemagne in 798, and the Saxon uprisings persisted after Widukind vanished. As he had for the previous 30 years, Charlemagne replied, and the outcomes were the same. Finally, in 804, Charlemagne expelled more than 10,000 Saxons to his kingdom's Neustria and replaced them with his own people in Saxony, effectively ending the conflict but earning the enmity of the Scandinavian kings, particularly Sigfried, who soon launched an attack on the Frankish region of Frisia. The fight may have continued for a while, but Sigfried passed away, and his successor filed a peace suit.

HOLY ROMAN EMPEROR

- Charlemagne was working fully on his own initiative throughout the Saxon Wars and his subsequent wars, and he paid very little heed to the papacy. However, none of the popes were protesting because Charlemagne's numerous endeavours aligned with or benefitted them personally. But by 800, it had become obvious that Charlemagne had more authority than the papacy, and there was nothing anybody could do to stop it.

- This was made evident when Pope Leo III was assaulted by a mob and had to flee in the streets of Rome.

- Roman nobility had incited the crowd by accusing Leo III of immorality and abuse of power in an effort to oust him and establish one of their own.

Coronation of Charlemagne - In response to Leo's request for protection from Charlemagne, Charlemagne promised to accompany Leo back to Rome to clear his record, which he later accomplished on the advice of his adviser, the scholar Alcuin.

- Leo was supposed to crown Charlemagne, who supposedly did not want this to happen and who allegedly stated he would never have entered the church if he had known it would take place.

- Whatever the case, it is generally known that when Charlemagne entered the cathedral, the crown was plainly visible, and he was undoubtedly knowledgeable enough to grasp it had it not been set there unintentionally.

- Charlemagne most certainly appreciated having the title, but he was not ready to give the papacy the power to use the Donation of Constantine as leverage against him.

- There is little question that the papacy attempted to exert some level of authority over Charlemagne through the coronation. Along with his frequent military triumphs, Charlemagne also improved the operation of churches, monasteries, and educational institutions all across his realm, which was now his empire.

- A foundation for increased wealth was previously laid by the technological developments that took place under the Merovingian Dynasty and Pepin the Short's rule. Crop rotation over three fields, the development and usage of the compound plough, which replaced the older scratch plough, and encouraging peasants to combine their labour and resources in farming were all examples of agricultural advancements that enhanced food output and improved land maintenance. By promoting the continued development of automation, such as the water mill for grinding grain instead of the earlier technique of grinding by human labour, Charlemagne expanded on the advancements.

- The Frankish Church under Pepin the Short underwent reform, led by St Boniface, who created monastic schools and brought discipline to ecclesiastical institutions. In order to facilitate administration, he also separated territories into parishes.

Merovingian Dynasty - Charlemagne benefitted from these developments by promoting them and surrounding himself with the most intelligent people of his time, such the scholar Alcuin of York, who stressed reading as a crucial component of devotion. The monastery schools spread this approach throughout Charlemagne's dominion, which raised literacy rates and produced better pupils.

- As Charlemagne dispatched commissioners from his headquarters at Aachen to the different provinces and parishes to ensure his orders were being properly carried out and that every area of his administration was working towards a common objective, Boniface's earlier reforms continued. However, it appears that there was no actual justification for these commissioners since individuals who Charlemagne gave positions of power to carried out their responsibilities out of personal allegiance to him rather than for the good of the state.

DEATH AND LEGACY

- After receiving Holy Communion, he passed away on 28 January, seven days after going to bed. He was 72 years old and in the 47th year of his reign. Charlemagne governed his dominion for 14 years until passing away in 814 due to natural causes. Louis the Pious had already been anointed as his successor by him in 813, but he was powerless to ensure that his legacy would go on after his death.

- That day, in the cathedral in Aachen, he was laid to rest. He was re-interred in the Karlsschrein, a casket made of gold and silver by Emperor Rederick II in 1215. Many of Charlemagne's followers were deeply affected by his passing, especially those in the literary group that had surrounded him at Aachen. He left a testament that distributed his assets in 811 but it had not been amended when he passed away. He dedicated the majority of his riches to the Church for charitable purposes. The totality of his empire barely survived for another century. Nevertheless, the split of it between Louis's own sons following his death set the groundwork for the current states of Germany and France.

- The initial issues for the empire, however, were brought on by Charlemagne's own decisions about Saxony decades before, not by any regressive or collapsing factors.

- In addition to destroying the area and killing thousands of people, the Saxon Wars also enraged the Scandinavian rulers, who waited until Charlemagne's death before launching the Viking invasions on France.

- Between 820 to 840, during Louis's reign, the Vikings regularly attacked France. While Louis made every effort to repel these assaults, he discovered that it was simpler to placate the Norse through land concessions and talks.

- Despite all of his flaws, Charlemagne's empire's various kingdoms would eventually come together to become the modern countries of Europe, and they could not have done so without his clear sense of purpose and natural ability to inspire people to want to follow him.

Image Sources

- https://www.worldhistory.org/uploads/images/10299.jpg

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saxon_Wars#/media/File:Charlemagne_against_Saxons.jpg

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charlemagne#/media/File:Kaulbach_Die_Kaiserkr%C3%B6nung_Karls_des_Gro%C3%9Fen.jpg

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Merovingian_dynasty#/media/File:Merovingian_dynasty.jpg