Edward the Martyr Worksheets

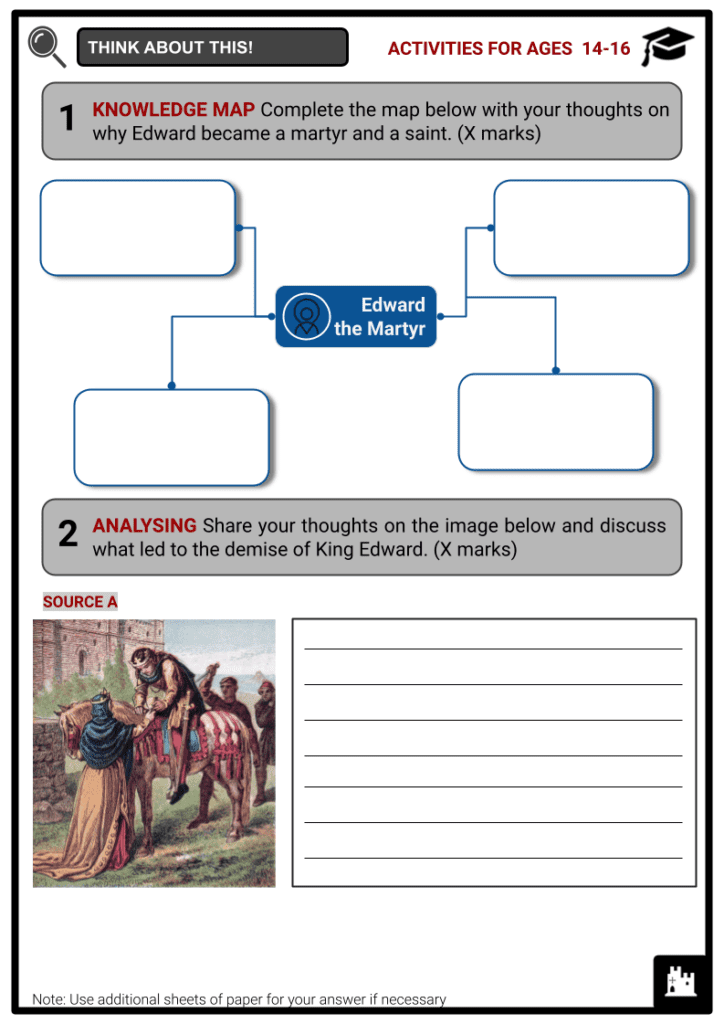

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Edward the Martyr to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Family

- Reign and Power Struggle

- Death

- Edward’s Relics

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about Edward the Martyr!

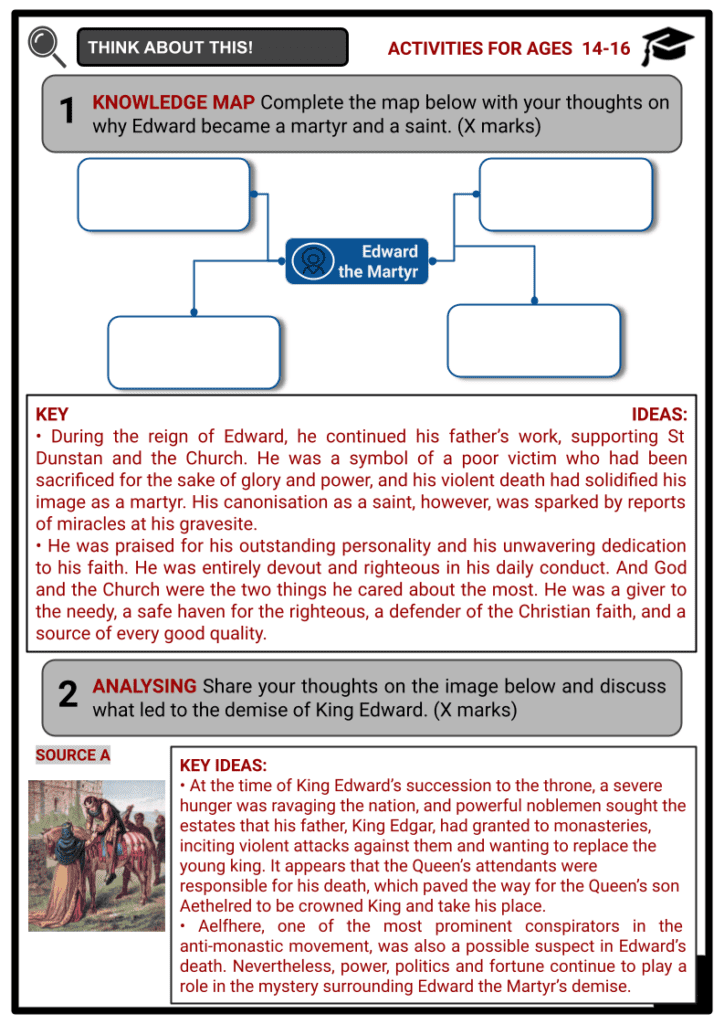

King Edward the Martyr succeeded his father, Edgar of England, as King of England in 975. His ascension to the throne at the demise of his father was contested by a faction led by his stepmother, Queen Elfrida, who was determined to secure the crown for her own seven-year-old son, Aethelred.

King Edward was assassinated after a short reign. Since Edward was a devout Christian and his death was blamed on ‘irreligious’ enemies, he was honoured as Saint Edward the Martyr in the year 1001. Edward was deeply lamented: it was thought that his remains performed miracles, and King Canute supported his cult.

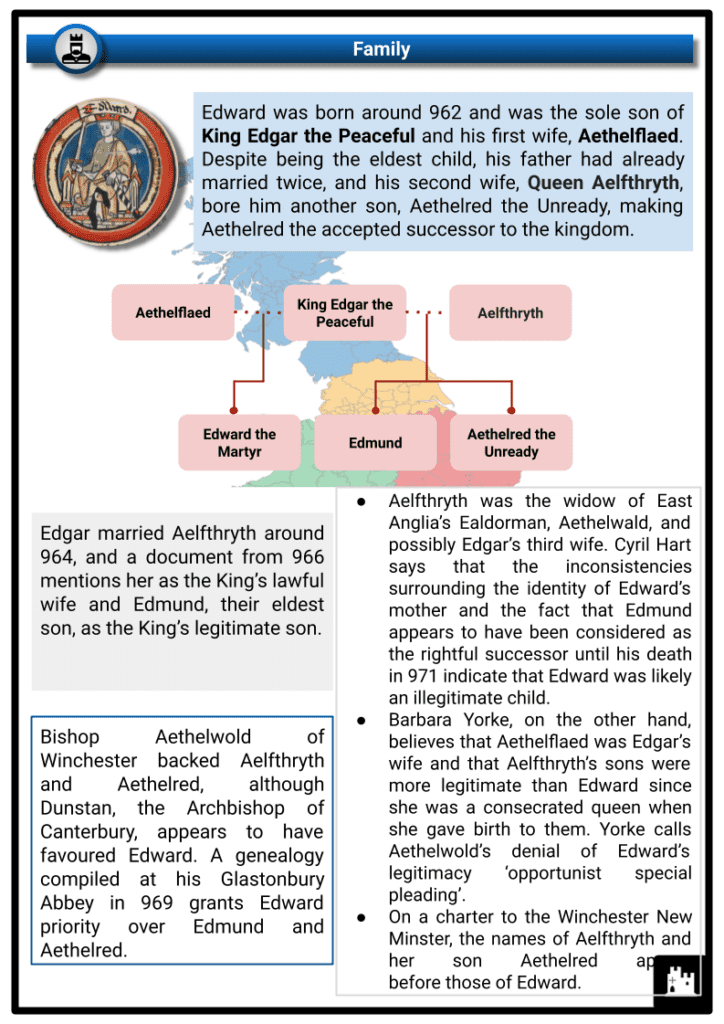

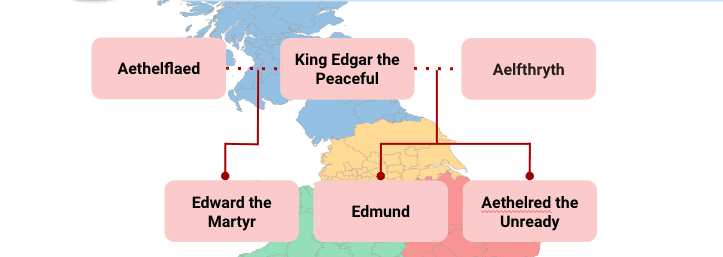

Family

- Edward was born around 962 and was the sole son of King Edgar the Peaceful and his first wife, Aethelflaed. Despite being the eldest child, his father had already married twice, and his second wife, Queen Aelfthryth, bore him another son, Aethelred the Unready, making Aethelred the accepted successor to the kingdom.

- Edgar married Aelfthryth around 964, and a document from 966 mentions her as the King’s lawful wife and Edmund, their eldest son, as the King’s legitimate son.

- Bishop Aethelwold of Winchester backed Aelfthryth and Aethelred, although Dunstan, the Archbishop of Canterbury, appears to have favoured Edward. A genealogy compiled at his Glastonbury Abbey in 969 grants Edward priority over Edmund and Aethelred.

- Aelfthryth was the widow of East Anglia’s Ealdorman, Aethelwald, and possibly Edgar’s third wife. Cyril Hart says that the inconsistencies surrounding the identity of Edward’s mother and the fact that Edmund appears to have been considered as the rightful successor until his death in 971 indicate that Edward was likely an illegitimate child.

- Barbara Yorke, on the other hand, believes that Aethelflaed was Edgar’s wife and that Aelfthryth’s sons were more legitimate than Edward since she was a consecrated queen when she gave birth to them. Yorke calls Aethelwold’s denial of Edward’s legitimacy ‘opportunist special pleading’.

- On a charter to the Winchester New Minster, the names of Aelfthryth and her son Aethelred appear

before those of Edward.

Reign and Power Struggle

- Edgar the Peaceful imposed monastic reforms on an apprehensive Church and aristocracy with the support of Dunstan, Archbishop of Canterbury; Oswald of Worcester, Archbishop of York; and Bishop Aethelwold of Winchester.

- By endowing the reformed Benedictine monks with the estates necessary for their upkeep, he displaced a large number of minor nobility and rewrote land leases and loans for the advantage of the monasteries.

- The new monasteries had expelled the secular clergy, many of whom were likely members of the nobility. While Edgar was alive, he was a firm advocate of the reformers, but after his death the discontent that these reforms had sparked came to light.

- Formerly unified in their support for the change, the prominent figures were now divided. There may have been tension between Archbishop Dunstan and Bishop Aethelwold. Archbishop Oswald was at odds with Aelfhere, Ealdorman of Mercia, while Aelfhere and his relatives were powerful competitors with Aethelwine, Ealdorman of East Anglia.

- In the later Anglo-Saxon period, the English Benedictine Reform, or Monastic Reform, of the English Church in the late tenth century was a religious and intellectual movement. By the middle of the tenth century, practically all monasteries were staffed by married, secular clergy. The reformers aspired to replace them with monks who followed the Rule of Saint Benedict and were celibate and contemplative. The movement was influenced by continental monastic reforms, with Dunstan, Archbishop of Canterbury, Aethelwold, Bishop of Winchester, and Oswald, Archbishop of York, serving as its major protagonists.

- In Anglo-Saxon England, Ealdorman traditionally referred to a man of high standing or royal birth.

- Aelfhere, Ealdorman of Mercia, was from a family that came to prominence in the tenth century. He was a leader of the anti-monastic reaction and an ally of Edward’s stepmother, Queen Dowager Aelfthryth, during the reign of Edward the Martyr.

- Aethelwine, Ealdorman of East Anglia, was one of the most prominent English noblemen of the tenth century. Aethelwine, along with Oswald of Worcester and Dunstan, was a leader among the supporters of King Edgar’s eldest son Edward, which placed him in opposition to his former sister-in-law Dowager Queen Aelfthryth and Aelfhere, Ealdorman of Mercia, following the death of King Edgar.

- These leaders had differing opinions on whether Edward or Aethelred should replace King Edgar upon his death. Neither the law nor the precedence provided much direction.

- Dunstan supported Edward, helped by his colleague Archbishop Oswald, while the Queen Dowager supported Aethelred, aided by Bishop Aethelwold. Aelfhere and his friends presumably backed Aethelred, while Aethelwine and his allies supported Edward.

- Edward was eventually anointed in 975 in Kingston upon Thames by Archbishops Dunstan and Oswald.

During Edward’s Reign

- Edward was crowned by Dunstan after being recognised by the Witan. Although he was only 13 years old, the young king had already shown signs of great holiness, and during his brief reign of three and a half years, he gained the hearts of his subjects through his remarkable virtues.

- Edward, or those who wielded authority on his behalf, also nominated several new Ealdormen to places throughout Wessex.

- In certain locations, the secular clergy who had been expelled from monasteries returned and, in turn, drove out the regular clergy. Archbishop Dunstan appears to have done nothing to help his fellow reformer, Bishop Aethelwold, during this time.

- In general, the magnates used the opportunity to revoke a number of Edgar’s grants to monasteries and compel the abbots to revise leases and loans in favour of the local aristocracy. In this sense, Ealdorman Aelfhere led the campaign against Oswald’s network of Mercian monasteries.

- During these disturbances, Aelfhere and Aethelwine appear to have been on the verge of open warfare at some point. Possibly connected to Aelfhere’s ambition in East Anglia and the attacks on Ramsey Abbey. Aethelwine, aided by his kinsman, Ealdorman Byrhtnoth of Essex and unnamed others, assembled an army and forced Aelfhere to retreat.

- Edward was selected as king, but nothing is known about his personality or his leadership skills. Perhaps as few as three (Anglo-Saxon) charters exist from Edward’s rule, leaving his brief reign in obscurity. In contrast, several charters from his father Edgar and half-brother Aethelred’s reigns remained.

- Two of the surviving Edward charters involve Crediton, where Edward’s previous mentor Sideman was bishop. All of the remaining Edward charters pertain to the royal heartland of Wessex.

- During Edgar I’s rule, all of the coin dies were cut in Winchester and then sent out to the various mints around the realm. During Edward’s reign, dies could be cut at places like York and Lincoln.

Death

- Some of the highest-ranking nobles, like Aelfhere and Aethelwine, were involved in conflict, with Aelfhere regarded as one of the anti-monastic movement’s most prominent leaders. The crisis was intensifying, and civil war appeared probable.

- Even with the help of the powerful Archbishop Dunstan, Edward’s leadership was insufficient to deal with the circumstances, and the seizure of monastery property persisted. In general, Edward’s reign was marked by crises.

Corfe Castle in Dorset - A significant number of these monasteries were destroyed, and their monks were forced to leave. However, the King and Archbishop Dunstan held steadfast in support of the Church and the monasteries. As a result, some of the nobility wanted to replace him with his younger brother Aethelred.

- On 18 March 978, Edward made the disastrous choice to travel to Corfe Castle to see his half-brother. Evening saw him arriving with a small number of men, who were greeted at the castle’s gates by Aelfthryth’s servants.

- The assassination occurred at the castle’s gates as Edward waited to be allowed in, maybe while being offered a drink of mead. The evil act was perpetrated here: Edward was still mounted on his horse when he was savagely stabbed, dying on his horse, which then bolted into the night, dragging his body along the ground.

- Edward was claimed to have been murdered on the orders of his stepmother, who wanted to put her own son on the throne. Aelfthryth and her factions, including Aethelred’s principal advisers, appear to be the most likely culprits of the assassination, due to the fact that Aethelred was only ten years old and far too young to have staged such an incident.

Edward’s Relics

- At the time of Edward’s death, legends about his remains began to circulate (martyrdom).

- After the assassination, the King’s body was dragged with one foot in the stirrup until it fell into a creek below the hill where Corfe Castle is located, where it was later discovered to have healing powers, especially for the blind.

- The monarch then issued an order for the body to be secreted away in a neighbouring shack as soon as possible. However, the blind woman who lived in the shack got her sight back and discovered the lifeless body of the King. This miracle is still commemorated at the church of St Edward at Corfe Castle.

- Before being exhumed, Edward’s remains rested in Wareham for a year. When Edward’s body was exhumed, it was discovered to be incorrupt, which was taken as a miraculous sign. The body was sent to Shaftesbury Abbey, a royally connected nunnery founded by King Alfred the Great.

- On the trip from Wareham to Shaftesbury, a second miracle occurred: Two handicapped men were brought near to the coffin, and those carrying it lowered it to their level, at which point they were instantly restored to full health.

- King Aethelred was overjoyed and ordered the bishops to raise his brother’s tomb from the earth and relocate it to a more fitting location.

- The bishops then removed the sacred relics from the grave and put them in a casket together with other holy relics at the holy site of the saints. This elevation of St Edward’s relics occurred on 20 June 1001.

- A cult soon developed around his memory. There are several interpretations on the rise of Edward’s cult. It is variously characterised as a popular movement or as an attack on King Aethelred by former Edward supporters.

- Alternately, Aethelred is seen as one of the driving causes for the propagation of Edward’s cult and Edith of Wiltons.

- In 1008, the All-English Council, presided over by Saint Alphege, Archbishop of Canterbury, officially canonised Saint Edward. It was on King Aethelred’s decree that the saint’s three feast days (18 March, 13 February and 20 June) would be observed all across England.

- St Edward is regarded as a Passion-Bearer in the Orthodox Church, a type of saint who embraces death out of love for Christ.

- Since 1001, his sainthood has been celebrated and glorified in honour of his martyrdom as a good Christian at the hands of those who were considered irreligious. Many members of the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Anglican Communion and the Roman Catholic Church all acknowledge and commemorate him to this day.