Etruscan Civilisation Worksheets

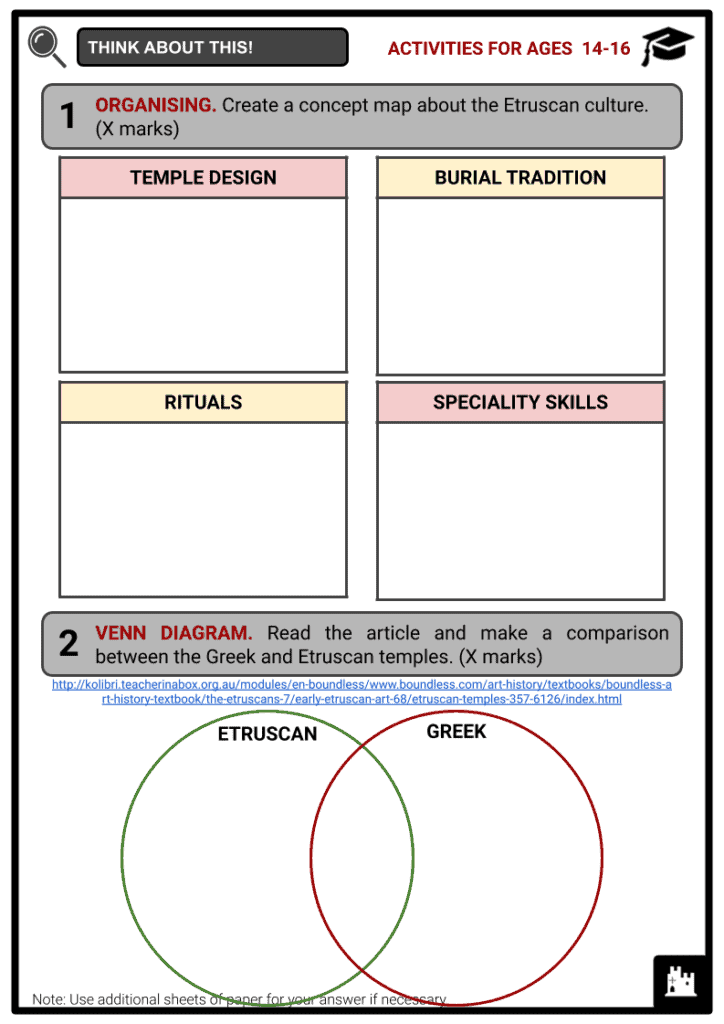

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Etruscan Civilisation to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Rise of the Etruscan Civilisation

- Etruscan Warfare

- Etruscan Government and Religion

- Etruscan Arts and Culture

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about the Etruscan Civilisation!

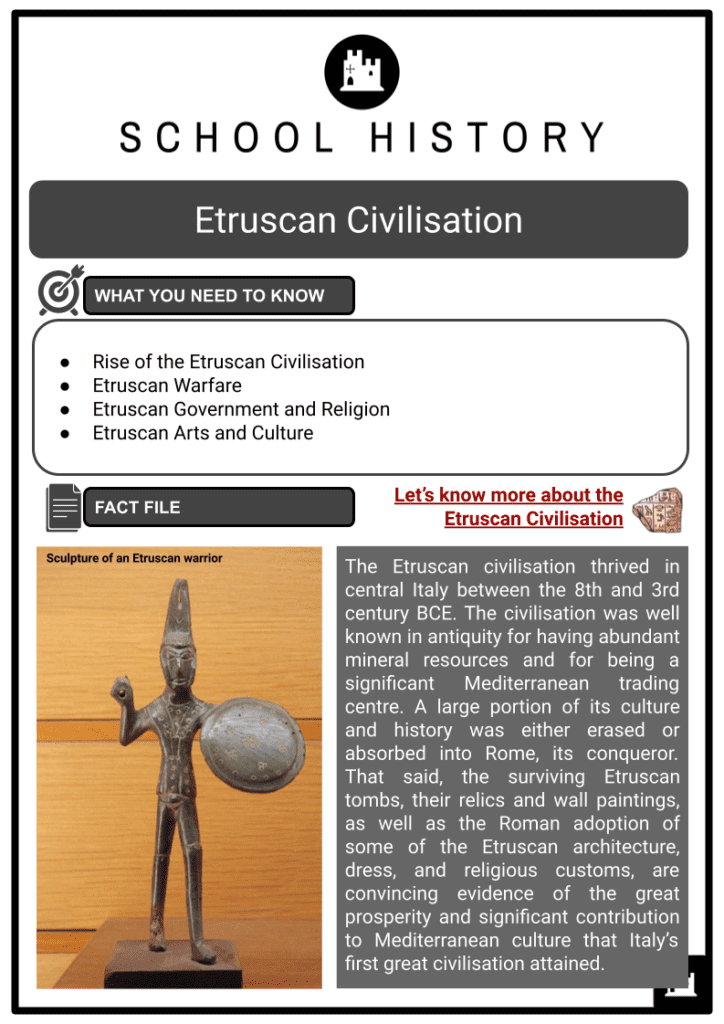

The Etruscan civilisation thrived in central Italy between the 8th and 3rd century BCE. The civilisation was well known in antiquity for having abundant mineral resources and for being a significant Mediterranean trading centre. A large portion of its culture and history was either erased or absorbed into Rome, its conqueror. That said, the surviving Etruscan tombs, their relics and wall paintings, as well as the Roman adoption of some of the Etruscan architecture, dress, and religious customs, are convincing evidence of the great prosperity and significant contribution to Mediterranean culture that Italy’s first great civilisation attained.

RISE OF THE ETRUSCAN CIVILISATION

- Around 1100 BCE, the Villanovan culture began to emerge in central Italy during the Iron Age. The title is misleading because the civilisation is actually an early form of the Etruscans. There is no proof of migration or conflict to imply that the two populations were distinct. The increased use of the region’s natural resources, which permitted the formation of communities, benefited the Villanovan culture.

- A part of the community was able to focus on industry and trade with the assurance of consistent, well-managed crops. The numerous bronze horse bits discovered in the sizable Villanovan cemetery just outside their settlements attest to the value of horses. Many of the Villanovan locations would go on to become significant Etruscan cities by the year 750 BCE, when the Villanovan culture had evolved into the Etruscan culture proper. The Etruscans were now set to become one of the most prosperous ethnic groups in the ancient Mediterranean.

- The only factors that united the separate city-states of the Etruscan civilisation were their shared religion, language and culture in general.

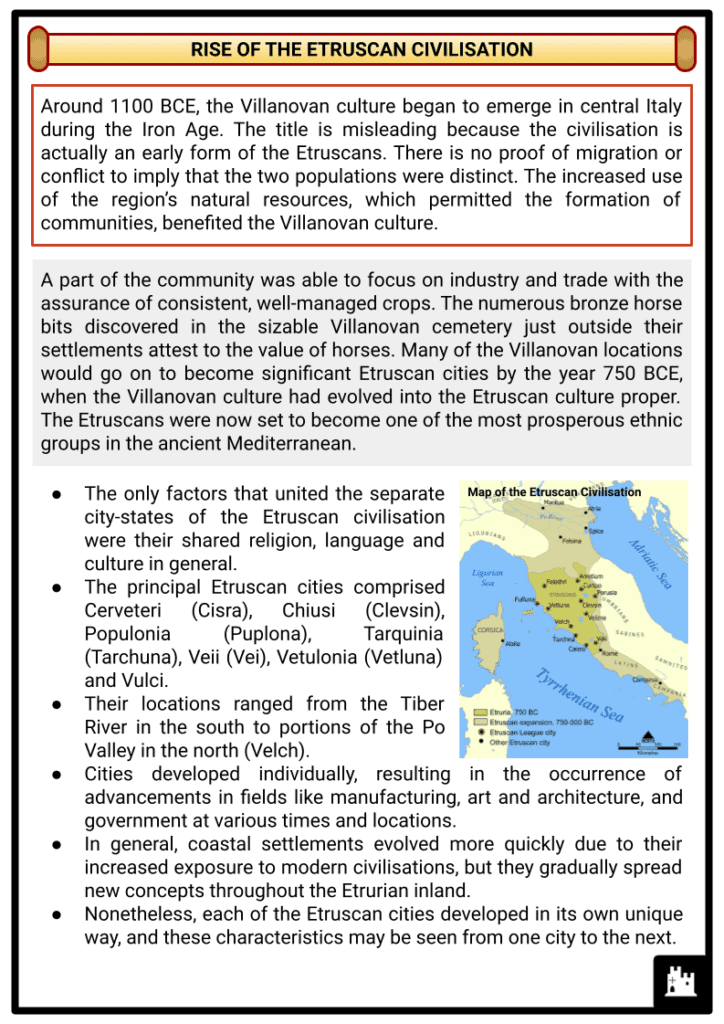

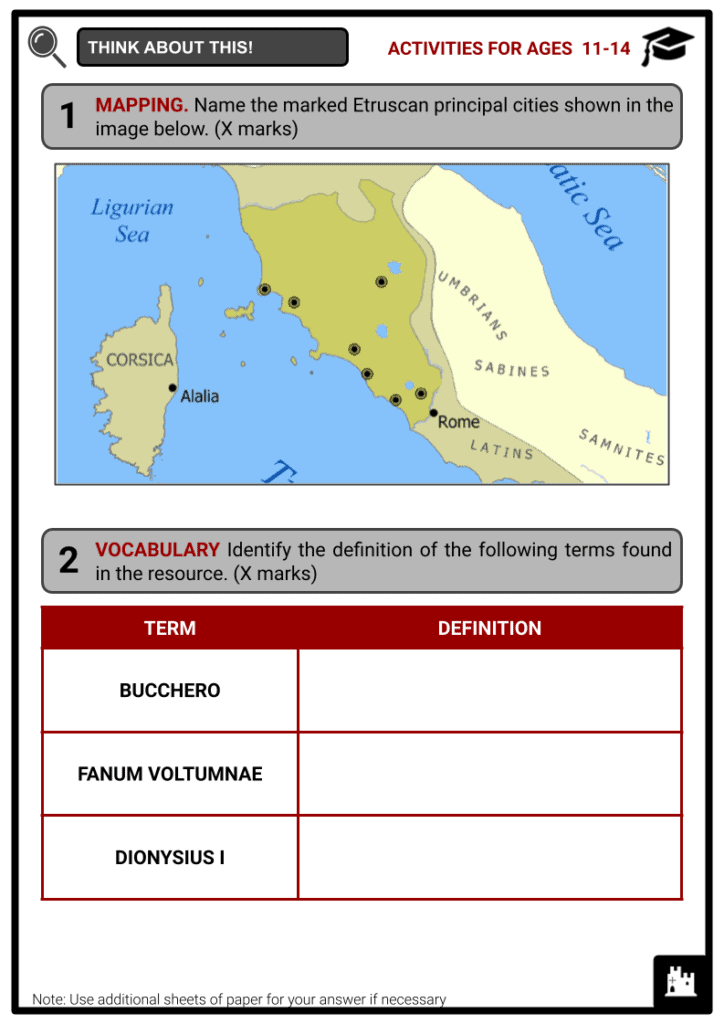

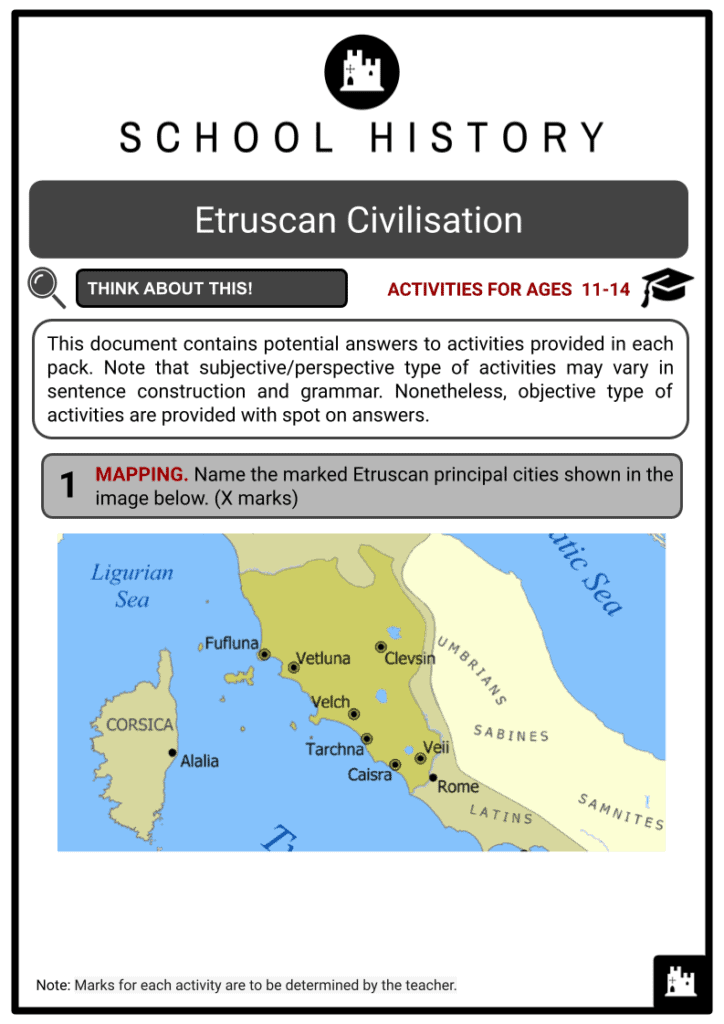

- The principal Etruscan cities comprised Cerveteri (Cisra), Chiusi (Clevsin), Populonia (Puplona), Tarquinia (Tarchuna), Veii (Vei), Vetulonia (Vetluna) and Vulci.

- Their locations ranged from the Tiber River in the south to portions of the Po Valley in the north (Velch).

- Cities developed individually, resulting in the occurrence of advancements in fields like manufacturing, art and architecture, and government at various times and locations.

- In general, coastal settlements evolved more quickly due to their increased exposure to modern civilisations, but they gradually spread new concepts throughout the Etrurian inland.

- Nonetheless, each of the Etruscan cities developed in its own unique way, and these characteristics may be seen from one city to the next.

Map of the Etruscan Civilisation - Rich local mineral resources, especially iron, the production of metal tools, pottery, and goods made of precious materials like gold and silver, tribes in northern Italy and across the Alps, and a trade network linking the Etruscan cities to other maritime trading nations like the Phoenicians, Greeks, Carthaginians and the Near East in general were the foundations of prosperity. The Etruscans exported iron, their own native bucchero pottery, and commodities like wine, olive oil, grain and pine nuts, while importing slaves, raw materials, and manufactured goods (particularly Greek pottery).

ETRUSCAN BATTLES

- As trade expanded starting in the 7th century BCE, the cultural effects of the resulting rise in intercultural contact also deepened. On the Tyrrhenian coast, semi-independent trading ports called emporia sprouted up, most notably Pyrgri, one of the ports of Cerveteri, where craftsmen from Greece and the Levant settled. During the so-called ‘Orientalising’ period, Greek and Near Eastern peoples would influence Etruscan culture in a variety of ways, including eating customs, dress, the alphabet and religion.

- At the Battle of Alalia (also known as the Battle of the Sardinian Sea), which took place in 540 BCE, Etruscan cities teamed up with Carthage to successfully defend their commercial interests against a Greek naval fleet. The Greeks frequently called the Etruscans despicable pirates due to their command of the seas and maritime trade along the Italian coast.

- However, Syracuse was the most important trading port in the 5th century BCE, and the Sicilian city joined forces with Cumae to defeat the Etruscans at the Battle of Cumae in 474 BCE. The Syracusan tyrant Dionysius I’s decision to assault the Etruscan coast in 384 BCE and demolish many of the Etruscan ports marked the beginning of worse things to come. These elements played a key role in the demise of numerous Etruscan cities between the 4th and 3rd centuries BCE due to the loss of trade.

- In the walls, Etruscan warfare appears to have initially been based on Greek ideas and the use of hoplites, who were deployed in a static phalanx formation while wearing a bronze breastplate, Corinthian helmet, greaves for the legs, and a large circular shield.

- However, from the 6th century BCE onwards, the greater number of smaller round bronze helmets would suggest a more mobile warfare. Even though there have been many chariots found in Etruscan graves, it’s likely that they were primarily used ceremonially.

- The production of coins dating back to the 5th century BCE reveals that, like many modern cultures, mercenaries were employed in combat.

- Many towns constructed massive defence walls with towers and gates throughout the same century.

- With the conquest of the Etruscans, a large empire was about to be established in the south, and all of these developments hint at a new military threat that would originate there.

- Even though they were mythical, some of Tarquinia’s early kings came from Rome in the 6th century BCE, but by the 4th century BCE Rome had stopped being the Etruscans’ inferior neighbour and was starting to show its power. Even if they would occasionally be their allies against Rome, the Celtic tribes’ northern invasions from the 5th to the 3rd century BCE did not benefit the Etruscan cause in any way. There would then be periodic fighting for about 200 years. Battles and sieges, such as Rome’s 10-year siege of Veii from 406 BCE and the siege of Chiusi and Battle of Sentinum, both in 295 BCE, were punctuated with peace treaties, alliances and short ceasefires.

Etruscan warrior head - Eventually, there could only be one winner due to Rome’s professional army, superior organisational abilities, superior personnel and superior resources, as well as the key absence of political unification among the Etruscan cities. A number of important cities fell in 280 BCE, including Tarquinia, Orvieto and Vulci. One of the last to resist the imperialistic expansion of what was quickly becoming the Roman Empire, Cerveteri fell in 273 BCE.

- In addition to founding colonies and repopulating territories with veterans, the Romans frequently slaughtered and sold the defeated into slavery.

- The conflict came to an end when numerous Etruscan cities sided with Marius in the civil war that Sulla ultimately won, after which he swiftly devastated the cities once more in 83 and 82 BCE.

- The Etruscans were Romanised, having their literature destroyed, their history erased, and their culture and language replaced by Latin and Latin ways.

- It would take 2,500 years and the nearly miraculous discovery of complete tombs filled with priceless artefacts and adorned with brilliant wall paintings before the world realised what had been lost.

ETRUSCAN GOVERNMENT AND RELIGION

- The monarchy that underpinned the early government of the Etruscan cities later gave way to an oligarchy that controlled all public positions and, where they existed, popular assemblies of citizens. A yearly gathering of the Etruscan League is the only indication of political links between cities. The only thing we know about this group is that the 12 or 15 most significant cities sent elders to a sanctuary named Fanum Voltumnae, which is unknown but was presumably close to Orvieto, where they gathered for religious purposes primarily.

- There is also a huge amount of proof that Etruscan cities periodically clashed and even drove out residents from smaller places. This is undoubtedly due to the struggle for resources that resulted from both population growth and a desire to control increasingly profitable trade routes.

- There were different social classes in Etruscan society, ranging from slaves and foreigners to female citizens and male foreigners. One’s membership in a clan was likely more significant than even one’s place of origin, with males of particular clan groups appearing to have dominated critical roles in the fields of politics, religion and justice. Even though they were still not treated equally to men and were not allowed to engage in public life outside of social and religious events, women had greater freedom than in most other ancient societies. For instance, they were entitled to inherit property in their own right.

- The gods for all those significant things, places, concepts and events that were believed to have an impact on or regulate daily life were included in the polytheistic religion of the Etruscans.

- Tin was at the top of the pantheon. However, it was likely assumed that, like most such individuals, he did not care much about ordinary human problems.

- There were a variety of different gods for that, including Usil, the Sun god, Thanur, the goddess of birth, and Aita, the goddess of the underworld.

- Veltha (also known as Veltune or Voltumna), who was closely associated with vegetation, appears to have been the national god of the Etruscans.

Fanum Voltumnae - Lesser characters included heroes like Hercules, who, along with many other Greek gods and heroes, was adopted, renamed and modified by the Etruscans to sit alongside their own deities, and winged girls known as Vanth, who appear to be messengers of death.

- Animal sacrifices, blood flowing onto the ground, music and dance were common rituals performed outside of temples dedicated to certain gods. In order to express gratitude to the gods for a favour rendered or in the expectation of soon receiving one, ordinary people would leave offerings at various temple locations. In addition to food, votive offerings were generally made in the shape of bronze or clay statuettes or vessels with engravings. Amulets were worn for the same reason, to ward off bad luck and evil spirits, especially by children.

- The inclusion of both priceless and common items in Etruscan tombs is a sign that they, like the ancient Egyptians, believed in an afterlife that was a continuation of the person’s life here on Earth. The next life, at least for those who are depicted in the wall murals in many tombs, likely began with a family reunion and continued with an endless round of enjoyable meals, games, dancing and music.

ETRUSCAN ARTS AND CULTURE

- Although they were designed similarly to Greek temples, Etruscan temples were different in that only the front porch often had columns, and this extended further outwards than those created by Greek architects. A higher base platform, an interior cella with three rooms, a side entrance, and substantial terracotta roof embellishments were other changes. These latter ones were initially seen in the structures of the Villanovan culture, but they later developed into far more grandiose sculptures, including life-size figures like the striding figure of Apollo from the Portonaccio Temple at Veii in 510 BCE.

- The Etruscans’ burial traditions weren't consistent throughout Etruria or even over time. Eventually, inhumation became more popular before cremation once more became the preferred method during the Hellenistic Period, but some locations changed more slowly.

- In fact, the greatest architectural legacy of the Etruscans is the interment of members of the same family through many generations in vast earthen graves or in elevated square buildings.

- Some circular tombs have a circumference of 40 metres. They frequently have stone-lined corridors leading to them and have corbelled or domed ceilings.

Banditaccia - The Banditaccia necropolis in Cerveteri is where you can view the cube-shaped monuments the best. Each one has a single doorway entry, and inside are stone benches used for burying the dead, sculpted altars, and occasionally stone stools.

- The graves’ neatly arranged rows show that town planning was more important in that period.

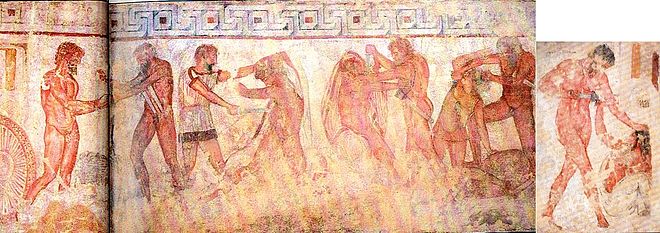

- The exquisite tomb wall murals of the Etruscans, which offer a singular and technicolour view into their lost world, are without a doubt the finest artistic legacy of this civilisation. The fact that just 2% of tombs were painted suggests that only the wealthy could afford such a luxury. The artists first outlined their works with chalk or charcoal before applying them directly to the stone wall or over a thin coat of plaster wash. Although there is little shading used, there are numerous colour shades used to make the images stand out vividly. The earliest paintings date to the middle of the sixth century BCE, but the themes remained constant over the ages, with a special fondness for dancing, music, hunting, sports, processions and dining scenes.

- There are occasionally historical scenes as well, such as those of the conflicts shown in the Francois Tomb at Vulci. The paintings reveal social attitudes, particularly towards slaves, foreigners and women, as well as daily living, eating habits, and attire in Etruscan society. For instance, the participation of married women at feasts and drinking gatherings (indicated by accompanying inscriptions) demonstrates that they had a higher level of social equality with their husbands than was the case in other ancient societies at the time.

- Another area of skill was pottery. The native pottery of Etruria, known as bucchero, has a peculiar, nearly black glossy surface. The style, which was created starting in the early 7th century BCE, frequently copied embossed bronze containers. Bowls, jugs, cups, cutlery, and humanoid vessels are among the popular shapes.

- Bucchero products were widely exported throughout Europe and the Mediterranean and were frequently found in tombs. A subsequent speciality was the creation of terracotta burial urns with a half-life-size, round-sculpted figure of the departed on the lid. These were painted, and despite occasionally being overly idealised, they exhibit accurate portraiture. These square urns frequently have relief sculpture on their sides depicting mythological subjects.

Francois Tomb - Since the Villanovan era, another Etruscan speciality had been bronze work. The material was used to create a wide variety of everyday objects, but miniature statuettes and bronze mirrors with etched motifs, again typically from mythology, are the best examples of the artist’s work. Finally, impressively high-quality, large-scale metal sculpture was created. There are very few examples that have survived, but those that have, most notably the Chimera of Arezzo, are proof of the artistry and ingenuity of the Etruscans.

Image Sources

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/67/Etruscan_warrior_near_Viterbe_Italy_circa_500_BCE.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/87/Etruscan_civilization_map.png/500px-Etruscan_civilization_map.png

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Etruscan_cippus_warrior_head.jpg

- https://i.ytimg.com/vi/f-INQfkrkCw/maxresdefault.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/6c/Banditaccia_%28Cerveteri%29DSCF6681.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/ad/Tomba_Francois_-_Liberazione_di_Celio_Vibenna.jpg/660px-Tomba_Francois_-_Liberazione_di_Celio_Vibenna.jpg