Act of Settlement (1701) Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the Act of Settlement (1701) to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- The Glorious Revolution

- The question of succession

- Provisions of the act

- Consequences of the act

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about the Act of Settlement (1701)!

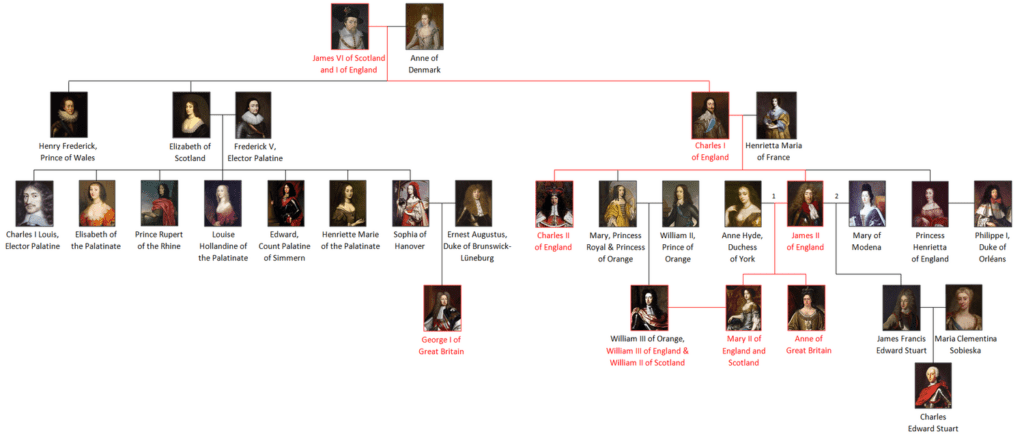

In 1701, Parliament saw the need to settle the succession in order to guarantee the continuity of the English crown in the Protestant line, after both of James II’s Protestant daughters failed to produce surviving heirs.

The Act of Settlement (1701) decreed that the English crown was to pass to Electress Sophia of Hanover and to her Protestant descendants. It ensured the exclusion of a Roman Catholic monarch. The act was instrumental in the creation of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and even today is still one of the main constitutional laws governing the succession to the throne of the United Kingdom and the other Commonwealth realms.

The Glorious Revolution

- The Glorious Revolution resulted in the overthrow of James II of England, and the subsequent placement of his daughter, Mary II, and her Dutch husband, William III of Orange, on the English throne. The coup that took place in 1688–89 was mainly motivated by political and religious conflicts.

- When James II from the House of Stuart ascended the throne in 1685, there was a growing tense relationship between the Catholics and Protestants in England.

- Being a Catholic himself, the king allowed freedom of religion, especially for the Catholics. He even favoured them to hold an office.

A portrait of James II by Peter Lely - This caused a further divide between him and the majority of the population.

- Furthermore, James II’s close diplomatic ties with France had caused intense conflict between the monarchy and Parliament.

- In 1687, James II dissolved Parliament and attempted to establish a new one that would not oppose him.

- At that time, the king’s Protestant daughter, Princess Mary, was the heir to the throne according to the royal line of succession.

- However, this situation changed when in 1688 the king had a son, whom he vowed to raise as a Catholic.

- For such reason, the Protestant population of England feared that this would result in a Catholic dynasty in the country.

- In April 1688, several of James II’s peers wrote a letter to Princess Mary’s husband, William of Orange, confirming their allegiance to him in the invasion of England.

- William prepared a naval fleet that landed in Torbay, Devon in November 1688.

- Meanwhile, the king was aware of the invasion, thus preparing his military troops, who left London to meet the invading forces.

- However, a number of his supporters, including members of his family, defected and sided with William.

- Due to this setback and his failing health, James II decided to retreat to London on 23 November 1688.

- He then agreed to a freely elected Parliament and granted general amnesty to all those who rebelled against him, while already planning to escape England.

- In December 1688, he disbanded his military army and successfully fled to France.

- In January 1689, a divided English Convention Parliament met to transfer the throne of England, Scotland and Ireland.

A depiction of William III and Mary II - The Radical Whigs, an influential political party whose members supported a constitutional monarchy, and a known opposition of James II’s absolute monarchy, proposed that William should take the throne as an elected king, which means that his power would be derived from the people.

- The Tories, another political party, argued that Princess Mary should be the queen and William be her regent.

- Parliament eventually came to a compromise and agreed to a joint monarchy with William III and Mary II as king and queen regnant.

- Furthermore, it was also agreed that both William III and Mary II should sign An Act Declaring the Rights and Liberties of the Subject and Settling the Succession of the Crown, more commonly known as the English Bill of Rights. The bill was signed in February 1689.

- This Bill of Rights recognised the constitutional and civil rights of the people. Moreover, it gave Parliament more power than the monarchy. The bill, likewise, acknowledged the rights for regular meetings of Parliament, free elections, and freedom of speech.

The question of succession

- The 1689 Bill of Rights declared that James II’s flight from England following the Glorious Revolution meant an abdication of the throne. Equally important was the establishment of the order of succession, proclaiming that Roman Catholics were barred from the throne of England for the welfare of the Protestant kingdom.

- The bill dictated that, after William III and Mary II, the throne would pass first to Mary II’s Protestant descendants, then to her sister, Princess Anne of Denmark, and her Protestant descendants, and thereafter to any Protestant descendants of William III by a later marriage should he outlive Mary II.

- The joint sovereigns, William III and Mary II, were unable to produce children.

- When Mary II died from smallpox at the age of 32 in 1694, William III became the sole ruler of the kingdom. The king did not seem likely to remarry.

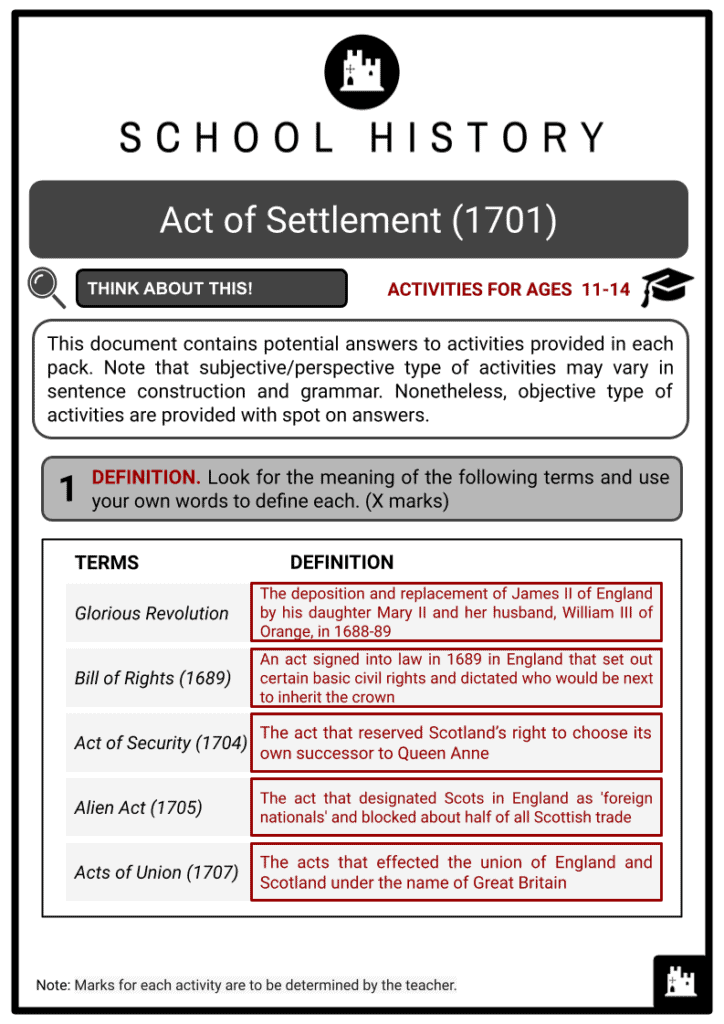

A painting of Princess Anne with her son, the Duke of Gloucester - In 1696, there had been an unsuccessful attempt by a faction loyal to the deposed James II to assassinate the king. This meant that the Jacobites continued to be a threat to the plan of maintaining a Protestant accession.

- By this time, Princess Anne was William III’s heir apparent. Her only son to survive infancy, Prince William, Duke of Gloucester, was next to her in the order of succession.

- However, in 1700, the Duke of Gloucester died at the age of 11. This cast uncertainty on the future of the Protestant kingdom.

- At that time, William III, who remained childless, was dying.

- Princess Anne was the only person remaining in the line of succession established by the Bill of Rights.

- The complete exhaustion of the defined line of succession was feared to encourage a restoration of James II’s line. Parliament thus saw the need to guarantee that the succession of future sovereigns remained within the Protestant faith with the enactment of the Act of Settlement in 1701.

Provisions of the act

- The need for the Act of Settlement (1701) was obvious as there was no confirmed heir to Princess Anne and the numerous supporters of the exiled James II posed a threat. Signed by William III, the act decreed that the crown was to pass to Electress Sophia of Hanover, granddaughter of James I, and to her Protestant descendants.

A diagram showing the relationship of Electress Sophia of Hanover to the House of Stuart - What were the constitutional provisions of the Act of Settlement?

- All future monarchs must join in communion with the Church of England, ensuring the exclusion of a Roman Catholic monarch.

- If a future monarch is not a native of England, England will not wage war for the defence of territories not belonging to the crown of England without the consent of Parliament.

- Judges are to hold office during good behaviour rather than at the sovereign’s pleasure. They can be removed only by both Houses of Parliament.

- Impeachments by the House of Commons are not subject to pardon under the Great Seal of England.

- No person who has an office under the monarch, or receives a pension from the crown, is to be a Member of Parliament.

- All government matters within the jurisdiction of the Privy Council are to be transacted there, and all council resolutions are to be signed by those who advised and consented to them. This clause was repealed early in Anne’s reign.

- No foreigner, even if naturalised or made a denizen, can be a Privy Councillor or a member of either House of Parliament, or hold any office, or have any grants from the crown. This clause was virtually repealed in 1870.

- No monarch may leave the dominions of England, Scotland or Ireland without the consent of Parliament. This clause was repealed in 1716 during the reign of George I.

- The act passed with little opposition, with only five peers voting against it in the House of Lords. At the time of its passage, the heiress presumptive to the English throne, Sophia, was in her seventies, but her son, George, proved to be a better option than the Roman Catholic Stuarts.

Consequences of the act

- Whilst the order of succession was now established, the threat of Stuart restoration remained.

- In 1701, Louis XIV of France abruptly proclaimed that James Edward Stuart, son of the deposed James II, was the rightful king of England, Scotland and Ireland. This succession issue had worried William III.

- To stabilise the relationship between England and Scotland and the solidarity between the two kingdoms, William III pushed for union negotiations by early 1702.

- However, he died in March 1702. Anne became queen in accordance with the Bill of Rights.

- The union negotiations continued following Anne’s ascension but issues in trade and taxation caused conflict between England and Scotland.

- Furthermore, the Scottish Parliament, displeased with the Act of Settlement, passed the Act of Security in 1704.

- Under this act, Scotland reserved the right to choose its own successor to Anne and explicitly required a choice different from the English monarch unless England were to grant free trade and navigation.

- The English Parliament then passed the Alien Act 1705, which designated Scots in England as 'foreign nationals' and blocked about half of all Scottish trade by boycotting exports to England or its colonies, unless Scotland came back to negotiate a union.

- In 1705, Anne asked for the union to make progress, which left the Scottish Parliament with no choice but to negotiate.

- Finally, in 1707, the Acts of Union came into effect, guaranteeing the Hanoverian succession to both English and Scottish thrones and freedom of trade for Scotland.

- This also effected the creation of the Parliament of Great Britain, binding the governmental systems of England and Scotland into one.

- As a consequence of this union, the Act of Settlement was extended to Scotland.

- Anne ruled Great Britain until her death in August 1714.

- The heiress presumptive, Sophia, died at the age of 83 a few weeks before the queen’s death.

- As a result, Sophia’s eldest son succeeded to the British throne as George I.

- A considerable number of Anne’s relatives with superior hereditary claims were bypassed owing to their Roman Catholic faith.

- The Act of Settlement continues to be one of the main constitutional laws governing the succession not only to the throne of the United Kingdom, but to those of the other Commonwealth realms. The Succession to the Crown Act (2013) amended the provisions of the Bill of Rights (1689) and the Act of Settlement (1701) to replace male-preference primogeniture with absolute primogeniture, and ended the provisions by which those who marry Roman Catholics are disqualified from the line of succession.

Image Sources

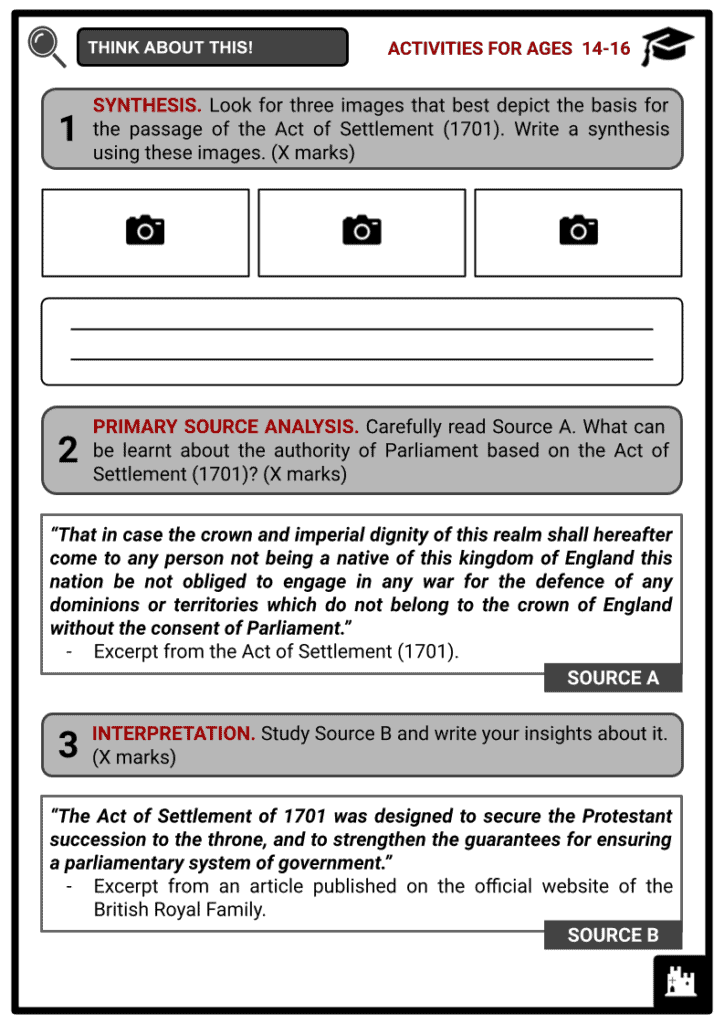

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1b/Act_of_Settlement_3323.jpg/800px-Act_of_Settlement_3323.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/99/James_II_by_Peter_Lely.jpg/800px-James_II_by_Peter_Lely.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/df/William%26MaryEngraving1703.jpg

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Queen_Anne_and_William,_Duke_of_Gloucester_by_studio_of_Sir_Godfrey_Kneller.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6e/House_of_Stuart.png/1500px-House_of_Stuart.png