Battle of Lepanto Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the Battle of Lepanto to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Historical Background of the Battle

- The Battle

- Legacy of the Battle

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about the Battle of Lepanto!

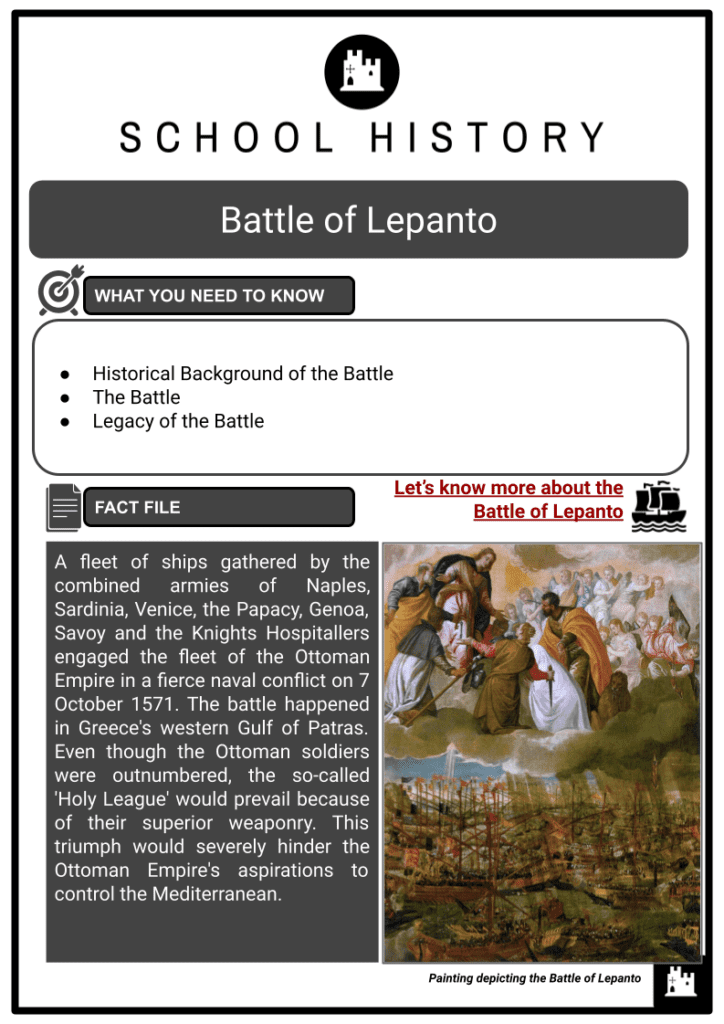

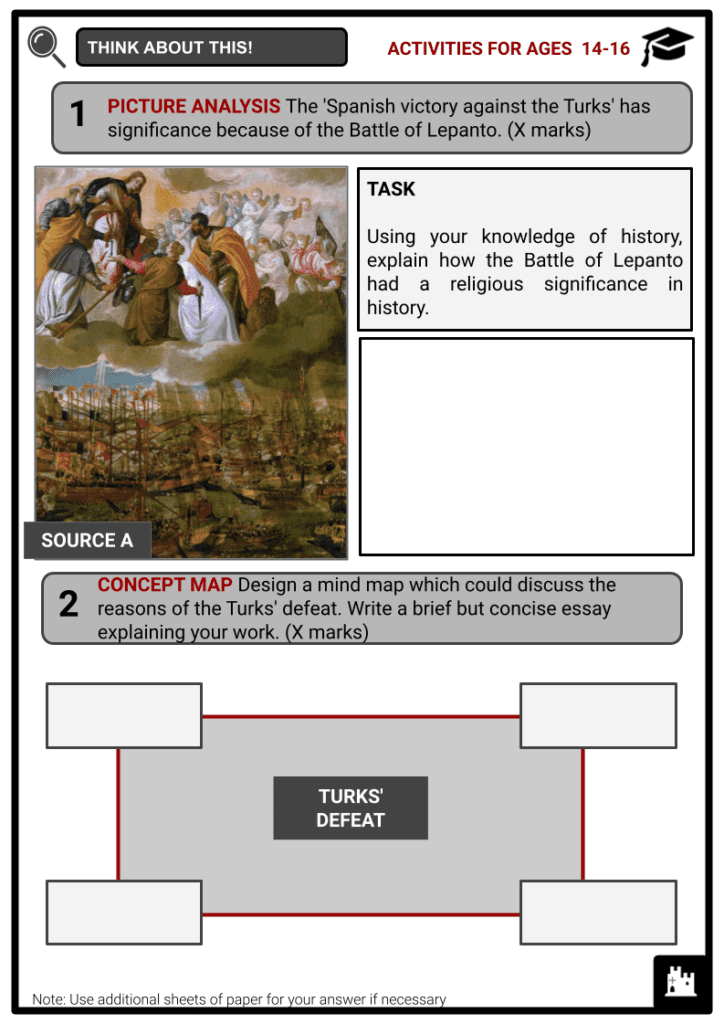

A fleet of ships gathered by the combined armies of Naples, Sardinia, Venice, the Papacy, Genoa, Savoy and the Knights Hospitallers engaged the fleet of the Ottoman Empire in a fierce naval conflict on 7 October 1571. The battle happened in Greece's western Gulf of Patras. Even though the Ottoman soldiers were outnumbered, the so-called 'Holy League' would prevail because of their superior weaponry. This triumph would severely hinder the Ottoman Empire's aspirations to control the Mediterranean.

Background of the Battle

- A brutal, terror-filled history spanning more than 1,300 years precedes what we see today. Today's conflict is much more secular than religious: it is a battle for legal and political structures, with hardly any discussion of religious dogma in the media. The Ottoman-Habsburg conflicts, in which the Battle of Lepanto essentially ended, and warfare between the Ottomans and the Republic of Venice, are placed within a larger historical perspective.

- Admiral Hayreddin Barbarossa led the Ottoman forces under Suleiman the Magnificent to maritime supremacy by defeating a combined fleet of the Holy League in 1538. In August 1571, Selim II, Suleiman's less talented son, was successful in retaking Cyprus from the Venetians. Although Selim's navy was destroyed at Lepanto, the Ottomans kept possessing Cyprus until 1878, when they turned it over to Great Britain.

- Because a pact between Venice and the Empire was in effect at the time, Selim's advisers cautioned him against conquering Cyprus. Because Cyprus was legitimately a part of the Empire — officially, Venice held the island as a tributary of the Sultan — Selim disregarded this.

- Selim initially asked that Venice give back the island before attacking. He also requested that Venice deal with the active pirates on the nearby seas. Don Juan de Austria, the half-brother of King Philip II of Spain and the illegitimate son of Emperor Charles V, expertly led the Holy League's fleet of 206 galleys and six galleasses (huge new galleys invented by Venetians that carried considerable armament). The safety of maritime trade in the Mediterranean Sea and the security of continental Europe were both gravely threatened by the Turkish fleet, which was seen as such by all alliance members.

- 12,920 sailors made up this Christian coalition fleet. Additionally, it carried nearly 28,000 combatants, including 10,000 highly skilled regular Spanish infantry, 7,000 German and Italian mercenaries, and 5,000 precious Venetian warriors.

- Additionally, Venetian rowers were primarily free citizens who could carry weaponry, enhancing their ship's fighting capability. In contrast, many of the galleys in other Holy League squadrons were rowed by enslaved people and prisoners. Enslaved people also argued a large portion of the Turkish fleets' galleys, frequently Christians who had been taken prisoner during earlier conquests and battles.

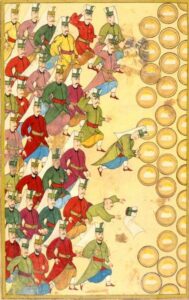

Detail of Tommaso Dolabella's artwork showing the Ottoman Navy (1632) - All combatants generally agreed that free rowers were superior. Still, due to rapidly rising costs, enslaved people, prisoners of war and convicts eventually supplanted them in all galley fleets during the 16th century, including those of Venice started in 1549. With the assistance of the corsairs Chulouk Bey of Alexandria and Uluj Ali, Ali Pasha could command an Ottoman army that included 222 war galleys, 56 galliots and a few smaller ships.

- The Turks had crews of skilful and knowledgeable sailors, but their elite corps of Janissaries suffered from some deficiencies. The Christians' numerical advantage in weapons and cannons on board their ships was significant and maybe decisive.

- According to estimates, the Turks only had 750 weapons with low ammo, compared to the Christians' 1,815 weapons. The Ottomans relied on their highly talented but ultimately inferior composite archers, while the Christians relied on their presumably more advanced arquebusiers and musketeers.

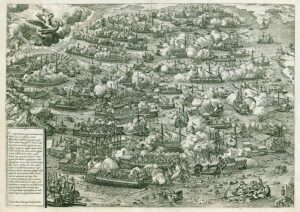

The Battle

- Before the Turkish fleet left them behind, the Left and Centre galleasses, which had been dragged a half mile forward of the Christian line, managed to sink two Turkish galleys and injure a few more. The Ottoman formations were also disturbed by their attacks.

- Doria discovered that Uluj Ali's galleys extended farther to the south than his own as the conflict got underway and turned south to avoid being outflanked. This indicated that he was acting even later. Uluj Ali ultimately outwitted him, turning around to attack the southern end of the Centre Division while taking advantage of the significant opening that Doria had created. The Turks attacked the galleasses when the war began because they believed them to be merchant supply ships.

- The incident was disastrous because it was estimated that the galleasses alone sank 70 Turkish Galleys with numerous cannons.

- The Christian fleet initially suffered in the north when Chulouk Bey used six galleys in an outflanking manoeuvre to get between the shore and the Christian North Division. Barbarigo was shot and killed by an arrow, but the Venetians held their ground after turning to face the danger. The appearance of a galleass saved the Christian North Division.

- After suffering significant damage, the Christian Centre managed to maintain its position with the assistance of the Reserve, while also doing substantial harm to the Muslim Centre. Doria was fighting with Uluj Ali's ships off the south coast, where she was getting the worst of it. In the meantime, Uluj Ali personally led 16 galleys in a swift assault on the Christian Centre, seizing six of them, including the Maltese Capitana, and killing all but three of the crew members.

HOLY LEAGUE

- John of Austria

- Agostino Barbarigo

- Giovanni Andrea Doria

OTTOMAN EMPIRE

- Sufi Ali Pasha

- Mahomet Sirocco

- Uluj Ali

- Although severely wounded by five arrows, its leader Pietro Giustiniani, before the Order of St John, was discovered alive in his hut. The conflict in the centre and Doria's south wing was turned by the Spanish reserves Juan de Cardona and lvaro de Bazan's intervention. Except for one of his captured subjects, Uluj Ali was forced to depart with 16 galleys and 24 galliots. Spanish tercios from three galleys and Turkish janissaries from seven galleys engaged in combat on the deck of the Sultana as the Ottoman Commander's ship was boarded.

- The Spanish were defeated twice with heavy losses, but with help from lvaro de Bazán's galley on their third try, they were successful. In defiance of Don Juan, Müezzenzade Ali Pasha was slain and beheaded.

- However, the Spanish flagships exhibition of his head on a pike significantly negatively impacted Turkish morale. Even though the Turks had lost the battle, troops of Janissaries continued to fight bravely.

- According to legend, the Janissaries eventually ran out of ammunition and began tossing oranges and lemons at their Christian foes, causing embarrassing hilarity among the general sorrow of battle. At around 4pm, the conflict came to an end. A total of 210 Turkish ships were lost, but 117 galleys, ten galliots and three fustas were captured and kept by the Christians in good enough shape.

Ottoman miniature painting depicting the Janissaries. - On the Christian side, 30 galleys had to be scuttled after suffering severe damage that required repairing 20 of them. The Turks only managed to keep one Venetian galley. All of their other spoils were abandoned and eventually taken back.

- When defeat was inevitable, Uluj Ali, who had taken the Maltese Knights' flagship, managed to remove most of his ships from the conflict. Despite having broken the tow on the Maltese flagship to escape, he continued to Constantinople, picking up additional Ottoman boats along the way, and eventually arrived with 87 ships. Sultan Selim II gave him the enormous Maltese flag in exchange for the honorary title 'klç' (Sword), and from that point on, Uluj was known as Klç Ali Pasha.

- While losing about 7,500 soldiers, sailors and rowers, the Holy League also managed to free roughly the same number of Christian prisoners. Around 25,000 Turks were killed, and at least 3,500 were taken.

Legacy of the Battle

- The battle is a 'rout or shattering defeat' in Turkish chronicles. This event gave half o f Christendom hope for 'the Turk's' demise because they saw this as the 'Sempiternal Enemy of the Christian'.

- Some Western historians consider it the greatest crucial naval battle in history, even though all but 30 of the Empire's ships and perhaps 30,000 soldiers were gone. However, despite the enormous triumph, the Holy League's division prohibited the winners from profiting from their victory. Arguments among the allies derailed plans to take the Dardanelles as a first step towards reclaiming Constantinople for Christendom. The Ottoman Empire reconstructed its navy and copied the effective Venetian galleasses with great effort. In addition to eight of the largest capital ships ever seen in the Mediterranean, more than 150 galleys and eight galleasses had been constructed by 1572.

- A new fleet of 250 ships, which included eight galleasses, were able to restore Ottoman naval dominance in the eastern Mediterranean in less than six months. The Ottoman possession of Cyprus was therefore officially recognised by the Venetians on 7 March 1573. The Turks had conquered Cyprus under Piyale Pasha on 3 August 1571 — just two months before the Battle of Lepanto — and had been ruled by them ever since.

- That same summer, the Ottoman navy wreaked havoc on the geographically exposed coasts of Sicily and southern Italy. An arm that has been severed cannot grow back. Still, a beard that has been shaved will grow even better for the shaver, according to a famous statement by a Turkish Grand Vizier:

"In taking Cyprus from you, we deprived you of an arm; in destroying our navy, you have just shaved our beard."

- Despite their assertions, the Ottoman losses were crucial from a strategic perspective. While it was relatively simple to replace the ships, it proved much more challenging to staff them because so many skilled sailors, rowers and soldiers had perished.

- The loss of the majority of the Empire's composite archers, which, in addition to ship rams and early firearms, were the Ottomans' primary embarked weapon, was particularly crucial. According to historian John Keegan, the Ottomans' losses in this highly skilled cadre of warriors were irreplaceable within a generation and symbolised 'the demise of a living culture'.

- In the end, it was also necessary to use a sizable number of prisoners to replace the enslaved Christians who had escaped. The Hafsid monarchy, which had been reinstated after Don Juan's armies recaptured Tunis from the Ottomans the previous year with the backing of Spain, was overthrown by the Ottomans in 1574.

- They restarted naval operations in the western Mediterranean because of their long-standing relationship with the French. The Ottoman conquests in Morocco, which had started under Süleyman the Magnificent, were finished in 1579 with the capture of Fez.

- Except for the strategically essential towns of Melilla and Ceuta, which Spain held, the whole Mediterranean coast from the Straits of Gibraltar to Greece came under Ottoman suzerainty after the formation of the Empire. However, the Ottoman navy's fighting capacity was severely diminished by the loss of so many of its seasoned sailors at Lepanto, as seen by the fact that they avoided conflicts with Christian navies in the years that followed.

- The Holy League's victory was significant historically because it signalled the end of Turkish dominance in the Mediterranean. The Turks had 80 ships sunk, 130 captured and 30,000 men killed (not counting the 12,000 Christian galleys enslaved people who were freed), while the Allies suffered losses of only 7,500 men and 17 galleys.

The Battle of Lepanto painted by Martin Rota - The Turks were frequently portrayed in European writing as a barbarian culture, destroying oppressors who had long oppressed their non-Muslim communities.

- However, wars like Lepanto and times of prolonged enmity and war are too easily defined as a clash of civilisations when reconstructing the tale of encounters and relations between the European and Ottoman realms.

- Some men were praised on both sides of the boundary, even when hostilities were being fought. For instance, Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire extended an invitation to Hayreddin Barbarossa, who had developed and trained the Ottoman navy to switch sides. Despite his refusal, this incident demonstrates that attitudes towards the 'other' were more nuanced than popular perception would have us believe.

- In 1534, Mulei Hassan, the deposed sultan of Tunis by Barbarossa, pleaded to Charles for assistance and was granted the right to reign as a Christian vassal. He didn't think twice about asking the Habsburgs for help against Suleiman's senior Admiral.