Download Bishops' Wars Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the Bishops' Wars to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Opposition to Charles I’s Church reforms

- The First Bishops’ War

- The Second Bishops’ War

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about the Bishops' Wars!

Fought in 1639 and 1640, the Bishops’ Wars were a pair of brief conflicts that occurred in England and Scotland. The wars broke out following Charles I’s attempts to impose uniform practices on the Church of England and the Kirk in 1637.

When the Kirk’s General Assembly refused to carry out the king’s reforms and removed bishops from the Church, Charles I saw no alternative to war. The wars ended in Royalist defeat and the signing of the Treaty of London in 1641, which confirmed Covenanter control of Scotland’s government and Church.

Opposition to Charles I’s Church reforms

- Following the 16th-century Protestant Reformation that brought about Scotland’s break with Rome, the Church of Scotland, or the Kirk, was formed. The Kirk adopted a Presbyterian structure and Calvinist doctrine, but the Reformation settlement was not formally ratified by the Crown.

- In 1567, James VI succeeded to the Scottish throne after his mother, Mary, Queen of Scots, abdicated the throne in favour of him.

- In 1572, the young king, who was brought up a Protestant, finally approved the religious settlement. This allowed Presbyterianism to dominate the Church.

- When Elizabeth I of England died in 1603, James VI inherited the English throne and was named James I of England.

- By this time, it was clear that the king believed that Presbyterianism was incompatible with a monarchy.

- Through his skilful manipulation of both Church and state, James VI and I gradually reintroduced parliamentary and then diocesan episcopacy in Scotland, limiting the independence of the Kirk.

- By the end of his reign, the Kirk had a full panel of bishops and archbishops, and General Assemblies met only at the king’s wishes.

- When James VI and I died in 1625, his second son and successor, Charles I, was crowned king of England and Scotland.

- He inherited a settlement in Scotland based on a balanced compromise between Calvinist doctrine and episcopal practice.

- Like James VI and I, who believed that a unified Church of Scotland and England was the first step in establishing a unified state, Charles I maintained this view and sought to implement this policy.

- However, the two Churches were very different in doctrine.

- Lacking the political judgement of his father, Charles I, with the assistance of the Archbishop of Canterbury, sought to modify the liturgical practice in Scotland to parallel that of England.

- He introduced the Prayer Book of 1637, a slightly modified version of the Anglican Book of Common Prayer.

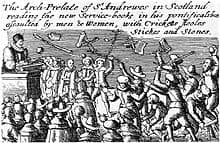

- Whilst the Prayer Book was devised by a panel of Scottish bishops, the king’s insistence that it be drawn up in secret and adopted without prior consultation resulted in widespread unrest.

- Amidst Charles I’s persistence to implement liturgical innovations, representatives from all sections of Scottish society agreed to a National Covenant in February 1638.

- The Covenant symbolised the Scottish resistance to liturgical reforms. The resistance gained popular support.

- Charles I agreed to a discussion but made it clear to the Royalists that he would refuse to make any concessions.

- When the Assembly became aware of this, it rejected the liturgical changes, removed bishops, who were seen as instruments of royal control, from the Kirk, and affirmed its right to meet annually.

- Charles I was then advised that there was no alternative to war.

- Following its introduction at St Giles Cathedral in Edinburgh in mid-1637, rioting broke out, believed to be set off by Jenny Geddes, and spread across Scotland.

Illustration of the 1637 riot over the Prayer Book

The First Bishops’ War

- Using his own financial resources, Charles I gathered a huge English army and planned on advancing on Edinburgh from the south. Additionally, Royalist troops would invade other parts of Scotland.

- The king’s plan was overly complex and the preparation of his troops were restrained by his lack of funds.

- Nevertheless, his huge English army, the vast majority of which were untrained, assembled at the border town of Berwick-upon-Tweed.

- Charles I also recruited foreign mercenaries from the Spanish Netherlands to compensate for his army’s lack of substantial weaponries and training.

- Meanwhile, the large Scottish army gathered a few miles away on the other side of the border.

- In May 1639, Charles I joined his troops at Berwick and announced that he would not invade Scotland, as long as the Covenanter army remained ten miles north of the border.

- The Scottish army advanced within the ten-mile limit, but fighting did not begin.

- By June, negotiations between the opposing parties started.

- On 18 June, Royalists and Covenanters fought at the Battle of the Brig of Dee south of Aberdeen, resulting in a Covenanter victory.

- On 19 June, the Pacification of Berwick was agreed, which stipulated that the king authorised a General Assembly at Edinburgh in August, to be followed by a meeting of the Scottish Parliament.

- Whilst both sides agreed to disband their armies, they remained suspicious and viewed the treaty as a truce.

- In an atmosphere of mutual mistrust, Charles I left Berwick and returned to London in July.

- The Kirk’s General Assembly met in August and confirmed the decisions taken at Glasgow, which were then ratified by the Scottish Parliament.

- When Charles I refused to ratify the decisions, Parliament continued to sit and passed acts which equalled a constitutional revolution.

- Preparations for another military confrontation continued.

- Convinced by his advisers to recall the English Parliament to aid him in financing a second war, Charles I issued writs in December 1639 for the first time since 1629.

- Furthermore, he also instructed his most capable adviser to ask the Parliament of Ireland for funds.

- In March 1640, despite violent opposition, the Irish Parliament approved a huge army to suppress the Covenanters.

- Meanwhile, when the Short Parliament convened in April, they demanded the king address grievances before they would approve subsidies.

- After just three weeks, Charles I dissolved the uncooperative Parliament and would have to rely on his own resources to fund the war.

The Second Bishops’ War

-

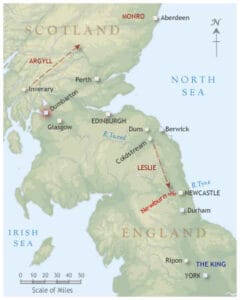

Map of the Second Bishops’ War By May and June 1640, the Covenanters readied for the defence of Scotland while a Scottish army, headed by the Earl of Argyll, was commissioned to pillage and burn the lands of Royalist clans in the Highlands. On the other hand, by early August 1640, the Royalist forces had assembled in Yorkshire and Northumberland, but the Irish army was not prepared to take part in the campaign against Scotland.

- The 20,000-strong Covenanter army gathered on the border with England.

- The English army in Yorkshire was awaiting the arrival of the king whilst the other in Northumberland focused on building up the defences of the border town of Berwick and appears to have ignored the mustering of the Covenanters.

- The Covenanter army then proceeded to mount a pre-emptive invasion of England.

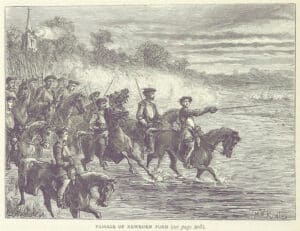

- Led by Alexander Leslie, the Covenanters bypassed the well-defended town of Berwick and marched straight for Newcastle.

- The Scots arrived at the outskirts of Newcastle and instead of attacking the strongly fortified northern approach to Newcastle, they marched west along the River Tyne to Newburn Ford, with the intention to secure control of the northern and southern banks of the Tyne and then to encircle Newcastle.

- At the Battle of Newburn, the English army, commanded by Lord Conway, guarded the ford, but the Scottish artillery completely dominated the English position.

- Under intense bombardment, the English troops deserted the earthworks and fled.

- The Scots then poured across the ford to take possession of the undefended river bank.

- When they reached Newcastle, they were surprised that Lord Conway and his army had withdrawn the garrison to Durham.

- The English defeat at Newburn Ford contributed to the collapse of the morale of the Yorkshire army.

- In September, Charles I summoned a Great Council of Peers at York, who almost unanimously advised the king to negotiate a truce with the Scots and to summon another Parliament in England.

- English and Scottish commissioners met at Ripon in October to negotiate a treaty.

- Signed on 14 October, the Treaty of Ripon led to the cessation of hostilities between the Royalists and the Covenanters while a permanent settlement was to be negotiated.

- In the meantime, the Scottish army was to occupy Northumberland and Durham, exacting an indemnity of £850 a day from the English government for its quarter.

- The Scottish government was also to be repaid for its expenses in prosecuting the war against England.

- In desperate need of money, Charles I was forced to summon the Long Parliament.

- Amidst civil unrest in London and the recent impeachment of his chief ministers, Charles I made a number of unexpected concessions at the Treaty of London, signed in August 1641:

- The resolutions of the Kirk’s General Assemblies that abolished episcopacy from the Scottish Church were ratified.

- The royal castles at Edinburgh and Dumbarton were to be used for defensive purposes only.

- No Scots would be censured or persecuted for signing the Covenant.

- The Scottish ‘incendiaries’ regarded as being responsible for creating the crisis were to be prosecuted in Scotland.

- Scottish goods and ships captured during the war would be returned.

- Publications against the Covenanters would be suppressed.

- The Scots would also receive the sum of £300,000 as recompense for the wars, which Parliament considered as ‘brotherly assistance’.

- The Bishops’ Wars and the concluding treaties therefore confirmed Covenanter control of government and the Kirk.

- Meanwhile, in England, Charles I’s royal power was continuously challenged by the Long Parliament. This would later lead to the English Civil Wars, occurring between 1641 and 1651.

Image Sources

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/52/Passage_of_Newburn_Ford.jpg/780px-Passage_of_Newburn_Ford.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a7/Riot_against_Anglican_prayer_book_1637.jpg/220px-Riot_against_Anglican_prayer_book_1637.jpg

- http://bcw-project.org/images/maps/bishops-war-2.jpg