Download Claudius Galen Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach Claudius Galen to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Table of Contents

Add a header to begin generating the table of contents

Summary

- Galen’s youth and early studies

- Life in Rome

- Galen’s work and intellectual profile

- Galen’s opinion on medical tradition

- Galen’s influence

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about Claudius Galen!

- Galen, born in Pergamum to Greek parents, saw himself as both a physician and philosopher. His contributions to medicine and philosophy became a major influence in Europe when he began as a court physician to Emperor Marcus Aurelius and the succeeding emperors in Rome. His views and findings on medicine, that was once thought of as absolute and complete, dominated Western medicine for thirteen centuries. This was the case until the Renaissance, when they began to be questioned, slowly and with great caution.

Galen’s youth and early studies

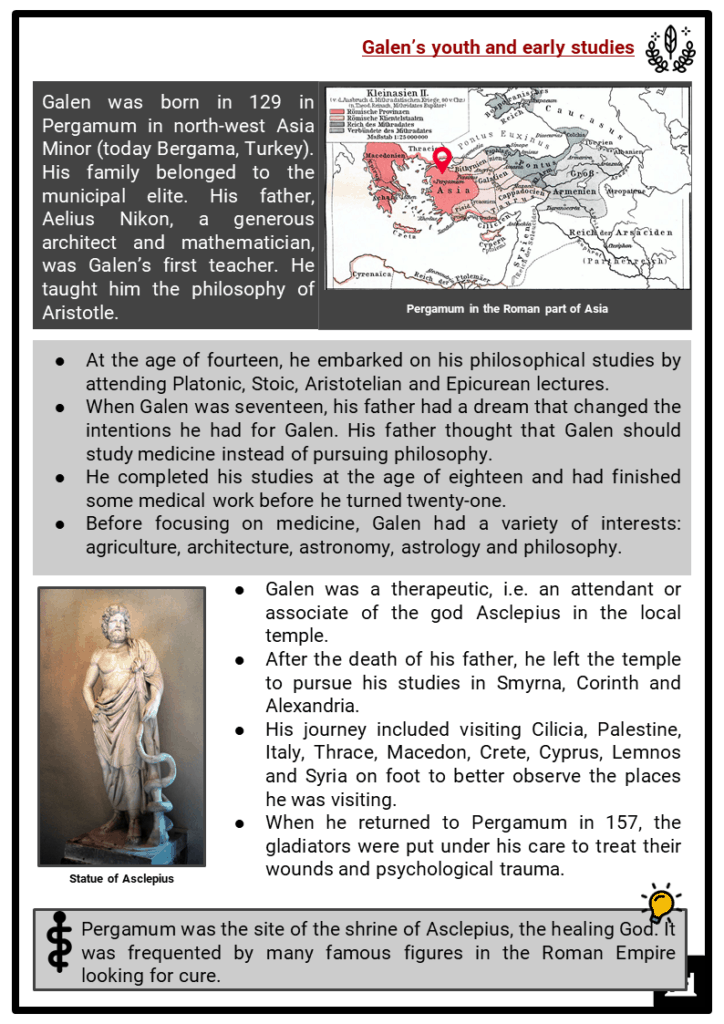

- Galen was born in 129 in Pergamum in north-west Asia Minor (today Bergama, Turkey). His family belonged to the municipal elite. His father, Aelius Nikon, a generous architect and mathematician, was Galen’s first teacher. He taught him the philosophy of Aristotle.

- At the age of fourteen, he embarked on his philosophical studies by attending Platonic, Stoic, Aristotelian and Epicurean lectures.

- When Galen was seventeen, his father had a dream that changed the intentions he had for Galen. His father thought that Galen should study medicine instead of pursuing philosophy.

- He completed his studies at the age of eighteen and had finished some medical work before he turned twenty-one.

- Before focusing on medicine, Galen had a variety of interests: agriculture, architecture, astronomy, astrology and philosophy.

- Galen was a therapeutic, i.e. an attendant or associate of the god Asclepius in the local temple.

- After the death of his father, he left the temple to pursue his studies in Smyrna, Corinth and Alexandria.

- His journey included visiting Cilicia, Palestine, Italy, Thrace, Macedon, Crete, Cyprus, Lemnos and Syria on foot to better observe the places he was visiting.

- When he returned to Pergamum in 157, the gladiators were put under his care to treat their wounds and psychological trauma.

- Pergamum was the site of the shrine of Asclepius, the healing God. It was frequented by many famous figures in the Roman Empire looking for cure.

Life in Rome

- In 162, at the age of thirty-three, he moved to Rome, bringing with him the new elements of Hippocrates’ medical science, which included the humoral theory and the origins of madness.

- In Rome, the Greek physician wrote and worked extensively, thus publicly demonstrating his knowledge of anatomy.

- In the competitive Roman environment, driven by a desire for affirmation, he began to challenge rivals in every field: from anatomical vivisections in front of an audience of intellectuals, to conferences well-attended by established doctors.

- The great success he obtained was double-edged, however. On the one hand, he gained a favourable reputation as an expert doctor, acquiring a vast clientele and the esteem of prominent personalities of the imperial circle. On the other, it aroused the envy and aversion of many rival colleagues.

- One of his patients was the consul Flavio Boeto, who introduced him to court where he became court physician to Emperor Marcus Aurelius.

- Later on, he also took care of Emperors Lucius Verus Commodus and Septimius Severus.

- Galen mainly spoke Greek, which in the philosophical environment of the time was more popular than Latin. In 166, he abruptly abandoned the capital to take refuge in Pergamum, probably due to the fear of a conspiracy by his rivals, or due to the manifestation in Rome of the first great epidemic.

- However, he was recalled in 168 by a letter from Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus who ordered him to reach the Aquileia camps to participate in the expedition against the Quadi and the Marcomanni. Galen spent the entire winter in the army.

- Yet, the epidemic continued to spread, and whilst claiming that he had received god Asclepius’s request in a dream, he finally succeeded in convincing Marcus Aurelius to allow him to return to Rome, where he could take care of Commodus’ health.

- Thus, in 169 he began a very productive period of his life. In fact, he was able to devote himself fully to his great literary production.

- He probably lived at court until the death of Marcus Aurelius in 180 and left the palace after the rise of Commodus, whom he considered to be the cruelest tyrant in history.

- Except for a brief return to Pergamum (166-169), Galen spent the rest of his life in the imperial court, writing and conducting experiments.

- He performed the vivisection of numerous animals to study the function of kidneys and the spinal cord.

- His favourite subjects were monkeys.

- According to his own testimony, he used twenty scribes to write down his words. Many of his works and manuscripts were however destroyed in 191, by the fire that broke out in the library of the Temple of Peace.

- The date of his death is conventionally fixed around the year 200. However, according to Al-Qifti’s work – the Tarikh al Hukama – written in 1249, Galen died in 216 in Sicily.

- He was buried in the province of Palermo (Italy), where Galen had stopped due to a serious illness while sailing back to Asia Minor.

- His first name, Claudius, was not documented before the Renaissance period, and such mistake is perhaps due to an incorrect decipherment of the expression Cl. Galenus present in the Latin codes: ‘Cl’ most likely meant ‘Clarissimus’.

Galen’s work and intellectual profile

- The abundance of autobiographical references in his works is not only vanity: by idealising his own autobiography, Galen depicted the ideal life and formation that a doctor should have.

- Ideal life and formation of a doctor

- A doctor should have in-depth knowledge of medical tradition, anatomy, the prognosis, and other demonstrative methods.

- A doctor is required to have an assiduous love of study, and contempt for worldly vanities.

- A physician must know the areas of philosophy that are essential to the doctor’s lifestyle (i.e. ethics, logic and physics).

- His biography is therefore proposed both as a model for disciples and as a criterion for evaluating the quality of doctors.

- Galen’s knowledge of medical science and philosophy, as well as his variety of interests and boundless literary production, makes him an exceptional case in the intellectual panorama of the 2nd century AD.

- Galen was, therefore, a doctor and a philosopher: illustrious patients such as the Emperor Marcus Aurelius considered him a professional philosopher who practised medicine as a marginal activity.

- In a paper entitled ‘The best doctor is also a philosopher’, he argued that one could not be a good doctor without knowing logic, physics and ethics.

- Emperor Marcus Aurelius described him as "Primum sane medicorum esse, philosophorum autem solum" (first among doctors and unique among philosophers).

- The vastness of his literary production reflects the variety of his interests: in fact, he wrote dozens of treatises on all aspects of medical knowledge, from epistemology to physiology and psychophysiology, from diagnostics to therapeutics and pharmacology.

- He composed a vast series of comments on the writings of Hippocrates as well as numerous polemical works against rival tendencies.

- Galen wrote a large number of philosophical treatises concerning logic, ethics, Plato, Aristotle, the Stoics, Epicurus, Favorinus, and others.

- Moreover, Galen wrote a series of books, some of considerable size, on literary criticism and linguistic erudition.

Galen’s opinion on medical tradition

- Galen’s attitude in this area was divided: on the one hand, stood Hippocratism, the humoral physio-pathology, clinical knowledge, prognostic and therapeutic expertise, indispensable for daily medical practice.

- On the other stood the Aristotelian thought and the great patrimony of the Alexandrian and Hellenistic anatomists, mainly Herophilos.

- According to Galen, the great problem of medicine was precisely in the loss of a unitary horizon caused by its division into rival schools (such as the philosophical ones) as opposed to the mathematical sciences which appeared much more united.

- Moreover, the dissent among the different traditions weakened medicine under the epistemological perspective, exposing it to the sceptics’ criticism.

- The School of Medicine is classified in three types: methodical, empirical, dogmatic.

- METHODICAL - The method of cure is not related to the knowledge of the cause of the disease.

- EMPIRICAL - The process includes testing by experience a hypothesis that had been advised by chance, and based on indefinitely many instances.

- DOGMATIC - The process consists of referring to a wide range of theoretical stances and inferring from signs and symptoms.

- These approaches reduced the cultural level of medicine, (which Galen would have liked to equal that of philosophy and other major sciences).

- Therefore, medicine was considered a simple manual technique.

- The simplistic theories of medicine argued that it only took six months to train a good doctor, and as a result, the art of medicine was granting access to a crowd of incompetents.

- Anatomy was actually more than a clinical practice since it enhanced medicine’s cultural dignity.

- It was also useful in the philosophical field since it taught how nature operates in every part of the body.

- By allowing to perfectly describe the relationship between the structures of the organs and their functions, anatomy constituted the scientific proof of the existence of an order and the providential structure of the world.

- Anatomy, therefore, could constitute the principle of a rigorous theology, and such knowledge was capable of giving medicine an overall cultural role.

- According to Galen, unifying medicine meant granting the profession

- homogeneity in the preparation of doctors,

- the reliability of therapies, and

- the expulsion of charlatans and incompetents.

- On the epistemological level, it meant building medical knowledge founded on coherent theories.

Galen’s Influence

- The authority of Galen dominated medicine until the 14th century.

- Most of the Greek works of Galen have been translated by Nestorian monks in the university and medical centre of Sasanid Jundishapur, in Persia.

- Muslim scholars soon translated his works into Arabic. Therefore, Galen’s works reached Western Europe in the form of a Latin translation from Arabic texts.

- Galen’s followers, believing that his findings were complete and absolute, considered further experiments unnecessary and did not make any advancement in the studies of physiology and anatomy for the next hundred years.

- In 1543, Andreas Vesalius, the Flemish physician, corrected Galenic anatomy and revolutionised the practice of medicine during the Renaissance.

Image sources:

[2.] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/c9/Galen-Pig-Vivisection.jpg