Cornish Rebellion 1497 Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the Cornish Rebellion 1497 to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Cause of the uprising

- Events of the uprising

- Outcomes of the uprising

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about the Cornish Rebellion 1497!

In 1496–97, Henry VII imposed a series of new policies that caused discontent among the people of Cornwall. The Cornish Rebellion, which sought the termination of the king’s war taxes, began in southern Cornwall and culminated in the Battle of Deptford Bridge near London in June 1497. While the rebellion also attracted the support of many people from Devon, Somerset and other English counties, the number of insurgents was later overwhelmed by the huge royal forces and the residents of London. The rebels failed to achieve their aims and their leaders were captured and executed. Cornwall continued to be burdened with high taxes until Henry VII redressed the Cornish grievances in 1508.

Cause of the uprising

- Henry VII successfully attained the English Crown upon the battlefield in 1485, concluding the Wars of the Roses. Given his weak claim to the throne, he faced various issues and therefore aimed to maintain a strong hold on the throne and pass on an unchallenged succession to his heir.

- To do this, Henry VII would have to:

- Maintain law and order and develop an effective government

- Take control of the nobility to prevent civil wars

- Strengthen the Crown’s control of England and foreign policy

- Improve the Crown’s financial strength

- In order to establish the Tudor dynasty and secure his position, the king ordered the detention of possible threats, rewarded his loyal supporters, and seized the lands and property of Yorkist enemies through the Acts of Attainder.

- Royal finances were one of the governmental priorities of Henry VII. While he initially lacked experience in financial administration, he recognised the importance of strong finances to secure his position. He enacted important changes in finances to raise revenues and to achieve financial stability.

Portrait of Henry VII - Having dealt with his enemies early in his reign, threats still existed as various Yorkist claimants to the throne made their moves.

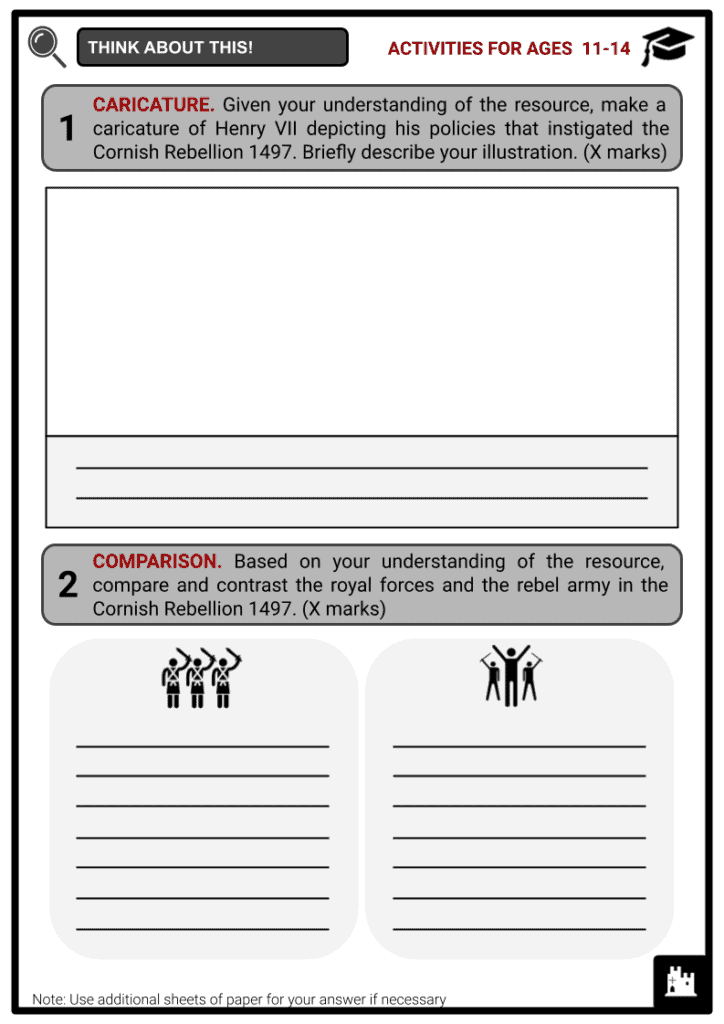

- Apart from these threats, non-dynastic rebellions such as the Yorkshire Rebellion and the Cornish Rebellion broke out during Henry VII’s rule. The principal reason for these rebellions was the king’s demands for money.

- During this period, Cornwall was a distinct region populated by Celtic peoples, similar to the Welsh and Bretons, and many of these people spoke Cornish rather than English.

- A series of actions by Henry VII in 1496–1497 resulted in the Cornish Rebellion:

- The king abolished Cornwall’s special privileges and set new tin mining laws.

- Owing to the significant economic impact of tin mining, Cornwall had established its own form of local governance, the Stannary Parliaments.

- The county enjoyed special privileges under the Stannary Law, one of the first incorporated laws in England. This included exemption from certain royal and local taxes.

- As a consequence, Cornwall developed a distinctive sense of independence and identity.

- However, in an effort to further secure the Tudor dynasty and undermine Cornish autonomy in 1496, Henry VII suspended the operation and privileges of the Cornish stannaries.

- The king demanded extremely high taxes from the Cornish to wage war against a pretender to the English throne.

- Henry VII felt threatened in 1496–97 with the invasion by James IV of Scotland and the pretender Perkin Warbeck.

- Warbeck started impersonating Richard, Duke of York, the younger of the Princes in the Tower, in 1491 in Ireland.

- His attempt to invade England in 1495 came to a defeat and the pretender was forced to flee to the court of the Scottish king, where he was offered men and a noble bride.

- These events prompted Henry VII to declare war against Scotland. He required funds for this campaign and so levied a forced loan, a double portion of fifteenths and tenths taxation and a special subsidy levy.

- The burden fell more heavily on Cornwall than most regions, especially in the collection of the forced loan.

- The king abolished Cornwall’s special privileges and set new tin mining laws.

- As Cornwall felt immediate hardships because of the king’s measures, the armed revolt of the people began.

Events of the uprising

- The rebellion started in southern Cornwall and ended at the Battle of Deptford Bridge near London on 17 June 1497.

- Beginning in the parish of St Keverne on the Lizard peninsula, the protest was instigated by the blacksmith Michael Joseph and the lawyer Thomas Flamank. It initially aimed to remove the chief advisers to the king found to be responsible for his taxation policies. It was participated in by two Members of Parliament.

- The riot quickly grew into a rebellion with as many as 15,000 people marching into Devon. It also attracted support in the form of provisions and recruits.

- The rebel army went from Somerset to Taunton, where they reportedly killed a tax collector. At Wells, they were joined by James Touchet, a member of the nobility with military experience. Touchet was welcomed as the leader of the rebellion. The army then proceeded towards London, marching via Salisbury and Winchester.

- Meanwhile, the king was occupied with the preparation for war against Scotland. Learning of the huge number and the proximity of the rebels to London, he decided to divert his main army of 8,000 men under Lord Daubeny to meet the rebels. There was also a general alarm among the residents of London, the majority of which took up arms and barricaded the walls of the city. On 14 June, a detachment of Lord Daubeny’s spearmen fought with the rebels near Guildford.

- After meeting the opposition, the rebel army chose to go south on the far side of London, believing that they would gain popular support from Kent. However, forces of Kentish men had been mobilised against them under loyalist nobles. Joseph was firm in preparing for battle, in contradiction to many who wanted to surrender as they only sought a change in the king’s chief advisers and taxation policies. This was followed by the desertion from the rebellion by the thousands.

- On 17 June, the Battle of Deptford Bridge, also referred to as the Battle of Blackheath, took place. As the rebel army approached London, they failed to gather new support. The king’s army of some 25,000 men outnumbered the 10,000-strong rebel army. Apart from being outnumbered, the insurgents lacked the supporting cavalry and artillery arms. The three battalions of the royal forces were deployed to surround the high ground of Blackheath where the rebel army had camped.

- The king’s battalion, under Lord Daubeny, attacked along the main road from London. The gunners and archers of the rebel army were able to inflict severe casualties on the company of spearmen but they were later driven off and killed.

- Lord Daubeny then took the onslaught up into the rebels’ main position on the heath. He was separated, surrounded by the enemy, and briefly captured. The rebels let him go unharmed.

- The rebels proved to be overwhelmingly outnumbered and poorly equipped. They were routed and their leaders Flamank, Joseph and Touchet were captured.

- Roughly a thousand rebels were killed in the rebellion, with the number of royal forces killed unknown.

Outcomes of the uprising

- When the battle was over, Henry VII went to the battleground, where he knighted the bravest of his troops. He then went back over London Bridge into the city and rewarded several others, including the mayor. An impromptu service of thanksgiving held at St Paul’s Cathedral was then attended by the king.

- On 27 June, Joseph and Flamank were executed at Tyburn. Henry VII accorded them the mercy of a quicker death following their sentence to be hanged, drawn and quartered.

- Meanwhile, Touchet, as a member of the nobility, was beheaded on 28 June at Tower Hill. The heads of the three rebel leaders were displayed on London Bridge.

- Cornwall continued to be burdened by monetary penalties as a result of the failure of the rebels to stop the taxes.

- Later in 1497, the pretender Warbeck travelled to Cornwall and attempted to take advantage of the recent unrest to claim the throne. Thousands of Cornish people joined his cause. This was often called the Second Cornish Rebellion. However, Warbeck once again did not succeed and was captured thereafter.

Commemorative plaque of the Cornish Rebellion - In 1508, Henry VII acted to redress Cornish grievances by reinstating the Stannary Parliaments.

- In 1997, Cornwall honoured the 500th anniversary of the rebellion by retracing the original route of the Cornish from St Keverne to Blackheath, London. Moreover, statues and plaques depicting the Cornish leaders were unveiled in commemoration. These reflected the importance of the rebellion in the establishment of Cornwall’s sense of identity and independence.

Image Sources

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/35/Old_map_of_Cornwall_-_001.jpg/795px-Old_map_of_Cornwall_-_001.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0d/Enrique_VII_de_Inglaterra%2C_por_un_artista_an%C3%B3nimo.jpg/800px-Enrique_VII_de_Inglaterra%2C_por_un_artista_an%C3%B3nimo.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/db/AnGofPlaqueBlackheath.jpg/220px-AnGofPlaqueBlackheath.jpg