Download English Reformation Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach English Reformation to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW

- The events that led to the English Reformation

- The main tenets of the English Reformation

- The impact of the English Reformation

KEY FACTS AND INFORMATION

Let’s find out more about the English Reformation!

- The English Reformation occurred following Henry VIII’s desire to divorce his wife Catherine of Aragon. Through this, the Act of Supremacy of 1534 was enacted which made the king head of the Church of England and cut out papal authority.

- Protestantism was welcomed in England after the death of Henry VIII and the ascension to the throne of Edward VI and subsequently Elizabeth I.

Theology of the Reformation

- Before delving into the English Reformation, it is necessary to understand the theological structure of Protestantism to draw a comparison with the type of reform that occurred in England during the reign of Henry VIII.

- Protestantism had its foundations in three fundamental principles.

- The doctrine of justification of faith alone, to the exclusion of good works and of any external sacramental action;

- The principle that the Scripture contains the Word of God which speaks directly to the soul and the conscience of the Christian and its supreme authority in matters of faith and discipline, to the exclusion of tradition and of any ecclesiastical hierarchy;

- The doctrine that the Church, which forms the mystical body of Christ, is the invisible society of the elect predestined to salvation.

- In essence, the Reformers claimed that these doctrines are taught in the Scripture and that they represent the genuine divine revelation which was altered and forgotten in the dogmatic and institutional degeneration that gave rise to the Roman Catholic system.

Overview of the Reformation in England

- In England, during the 16th century, reformation began when the Church of England separated from the Roman Catholic Church and the papal authority. Several factors were emphasised such as the continuous Protestant Reformation in Europe.

- In England, a strong resentment against the financial exploitation of the British Church and the people by the Roman Curia, and especially against the papal grants of British ecclesiastical benefices to foreigners, had long been widespread

- among all classes and had found expression in repeated attempts to curb those abuses and to restrict the authority and jurisdiction of the Church.

- Wycliffe’s revolutionary theories about the Church and the Papacy had gained a large following and though the movement which took its inspiration from his teaching (the Lollards) was severely repressed, it had not disappeared altogether.

- John Wycliffe (1320s – 1384) was an English theologian, priest, and a professor from the University of Oxford. He was influential and a forerunner to the Protestant Reformation due to his ideas. He criticised the luxurious life of the clergies. Furthermore, he was an advocate of the Bible translation into the common language. By 1382, he produced a translation known as Wycliffe's Bible.

- Another factor was that humanism imported into England from Italy found fertile ground. Lastly, the ideas and writings of the continental reformers had found their way to England and created a keen interest in the new doctrines among many of the intellectual classes.

- Nonetheless, the British revolt against the pope was not a consequence of the Reformers’ work and their theological considerations. Henry VIII had a strong and genuine Catholic faith: the monarch implemented methods of harsh repression against Protestant infiltrations in England and also wrote a treaty in 1521, the Sacraments, in which he refused Martin Luther and his ideas.

- When Henry VIII detached from the Church of Rome, England nonetheless remained a Catholic country (Hobbs 2000).

- Henry VIII considered his wife Catherine of Aragon an embarrassment since (I) she had not borne a male son; and (II) her marriage with the king was suspect. The pope rejected the king’s request to annul his marriage. However, Henry was already infatuated with Anne Boleyn and wished to take her as his new wife.

- When the pope threatened the English monarch with ex-communication, Henry answered with the Act of Supremacy (1534), which recognised him as the supreme head of the Church of England to the exclusion of the pope or any other ecclesiastical authority.

- Anyone refusing to take the ‘oath of supremacy’ to the king, among them the Bishop of Rochester John Fisher, and the ex-chancellor and thinker Sir Thomas More, were executed.

- Apart from the abolition of the papal supremacy over the Church and the suppression of monasteries and confiscation of their estates and possessions, Henry did not change the doctrines and the institutions of the Church. As Hobbs (2000) suggests, one of the reasons that may have pushed the king to take possession of the Church’s ‘money and land’ was the accumulation of wealth.

The Ten Articles

- In 1536, the Ten Articles represented the Church of England’s new faith, and rather than including the seven sacraments, it only presented three of them, i.e. baptism, penance and the Eucharist (Hobbs 2000). What had happened to the sacraments of confirmation, ordination, marriage and last rites? Simply, they were considered to be less important than the ones stated above.

- Below are the first five articles that relate to sacraments:

- That Holy Scriptures and the three Creeds are the basis and summary of the true Christian faith.

- That baptism conveys remission of sins and the regenerating grace of the Holy Spirit and is necessary for children as well as adults.

- That penance consists of contrition, confession and reformation, and is necessary to salvation.

- That the body and blood of Christ are present in the elements of the Eucharist.

- That justification is remission of sin and reconciliation to God by the merits of Christ, but good works are necessary.

- Moreover, the ten articles debate sacred images, pilgrimages, and bans ‘some holy days and saints’ days:

- That images are useful as remembrances but are not objects of worship.

- That saints are to be honoured as examples of life, and as furthering our prayers.

- That saints may be invoked as intercessors, and their holidays observed.

- That ceremonies are to be observed for the sake of their mystical signification, and as conducive to devotion.

- That prayers for the dead are good and useful, but the efficacy of papal pardon, and soul-masses offered at certain localities, is negatived.

The Institution of a Christian Man

- In 1537, the newborn Church of England formulated the ‘Institution of a Christian Man’ which intended to give further instructions on the new faith: it attempted to address the ‘question of purgatory and the status of the four missing sacraments in the Ten Articles’ (Hobbs 2000).

The Six Articles

- In the Six Articles (1539), no concessions were made concerning the celibacy of the clergy, the celebration of private masses, and the practice of confession. In the meanwhile, harsh measures were taken against those who professed Lutheran doctrines, many being executed and others fleeing to Protestant Germany and Switzerland.

- The articles read in the following way:

- First, that in the most blessed Sacrament of the Altar, by the strength and efficacy of Christ’s mighty word, it is spoken by the priest, is present, under the form of bread and wine, the natural body and blood of Our Saviour Jesu Christ, conceived of the Virgin Mary, and that after the consecration there remaineth no substance of bread and wine, nor any other substance but the substance of Christ, God and man;

- Secondly, that communion in both kinds is not necessary ad salutem, by the law of God, to all persons; and that it is to be believed, and not doubted of, but that in the flesh, under the form of the bread, is the very blood; and with the blood, under the form of the wine, is the very flesh; as well apart, as though they were both together.

- Thirdly, that priest after the order of priesthood received, as afore, may not marry, by the law of God.

- Fourthly, that vows of chastity or widowhood, by man or woman made to God advisedly, ought to be observed by the law of God; and that it exempts them from other liberties of Christian people, which without that they might enjoy.

- Fifthly, that it is meet and necessary that private masses be continued and admitted in this the King’s English Church and Congregation, as whereby good Christian people, ordering themselves accordingly, do receive both godly and goodly consolations and benefits; and it is agreeable also to God’s law.

- Sixthly, that auricular confession is expedient and necessary to be retained and continued, used and frequented in the Church of God.

Reformation After Henry VIII

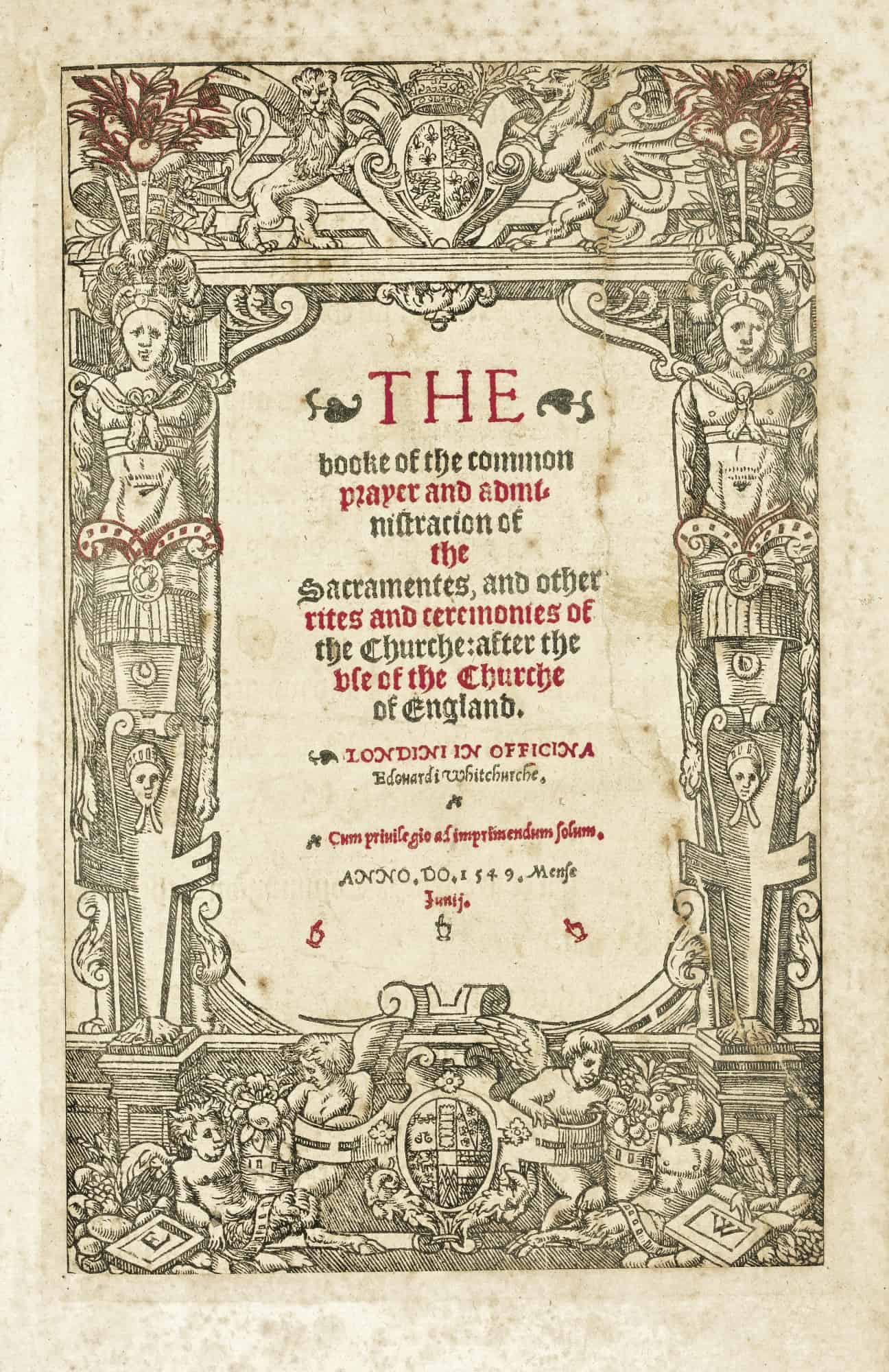

- During the reign of Edward VI and the regency of the Duke of Somerset, however, the articles of Henry VIII were abolished, and the Reformation had its beginnings in England with the adoption of the Book of Common Prayer (1549) and the formulation of Forty-two Articles of Faith (1552).

- The reign of Queen Mary (1553-1558) marked the restoration of Catholicism under the supervision of the Papal Legate, Cardinal Pole, but, against his advice, the restoration was accompanied by savage persecution of the Protestants, one of the first victims being Archbishop Cranmer of Canterbury.

- The accession of Elizabeth I in 1558 again turned the tables in favour of the reform. The oath of supremacy was re-established; the Articles of Edward VI were revised in 1563 as the Thirty-nine Articles, and the Book of Common Prayer became the normative doctrinal and liturgical code of the Episcopal Church of England; and savage persecution was now visited on the Catholics.

How the Doctrinal Change was Perceived in England

- Henry VIII’s revolt against Rome did not mar the introduction of the Reformation by Edward VI, and its restoration by Queen Elizabeth did not meet with any successful opposition from the English people.

- The majority of the clergy, high and low, adapted themselves more or less willingly to the new religious regime, and the British aristocracy, many members of which received in royal grants a good share of the confiscated monastic possessions, stood almost solidly behind the new order of things.

Image sources:

[1.] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/c6/Henry_VIII_National_Maritime_Museum.jpg

[2.] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/e1/Thomas_More%C2%B4s_farewell_to_his_daughter.jpg

[3.] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/78/Book_of_common_prayer_1549.jpg