Galileo Galilei Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Galileo Galilei to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Early Life

- Contribution to Science

- Conflict with the Church

- Death and Legacy

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about Galileo Galilei!

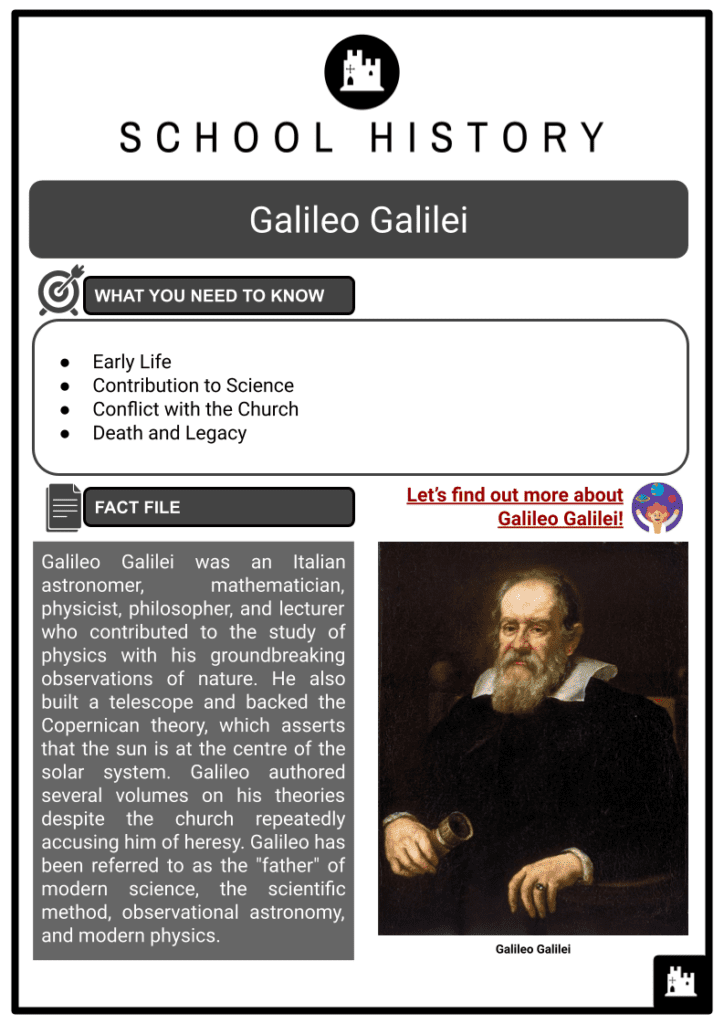

Galileo Galilei was an Italian astronomer, mathematician, physicist, philosopher, and lecturer who contributed to the study of physics with his groundbreaking observations of nature. He also built a telescope and backed the Copernican theory, which asserts that the sun is at the centre of the solar system. Galileo authored several volumes on his theories despite the church repeatedly accusing him of heresy. Galileo has been referred to as the "father" of modern science, the scientific method, observational astronomy, and modern physics.

EARLY LIFE

- Galileo was the first of six children born to Vincenzo Galilei, a lutenist, composer, and music theorist, and Giulia Ammannati, who wed in 1562, in Pisa, Italy (previously part of the Duchy of Florence). Galileo went on to become a skilled lutenist and would have picked up a skepticism for authority from his father at a young age.

- Galileo Galilei was raised by Muzio Tedaldi for two years after his family relocated to Florence when he was eight years old. Galileo studied under Jacopo Borghini in Florence after moving there with his family when he was ten years old. Between 1575 to 1578, he received education, specialising in logic, at the Vallombrosa Abbey, which is located approximately 30 km southeast of Florence.

- Galileo enrolled at the University of Pisa in 1583 to study medicine.

- He quickly developed a passion for physics and mathematics.

- He was exposed to the Aristotelian worldview while studying at Pisa.

- The Aristotelian worldview was the only one recognised by the Roman Catholic Church and the preeminent source of scientific knowledge at the time.

- Galileo initially endorsed the Aristotelian viewpoint.

- He planned to become a university professor.

- Galileo left the University of Pisa in 1585 without receiving a degree due to financial issues.

- After college, Galileo continued his studies in mathematics while working as a part-time instructor to support himself. He started his two-decade study on moving things around this period and wrote ‘The Little Balance’, which described the hydrostatic principles of weighing small amounts, earning him considerable notoriety. As a result, he was offered a teaching position at the University of Pisa in 1589.

- Galileo carried out falling object experiments while at the University of Pisa.

- He wrote the famous work ‘Du Motu (On Motion)’ which challenged Aristotelian notions of motion and falling objects.

- Galileo's strong opinions and attacks on Aristotle caused him to be marginalised by his peers.

- His agreement with the University of Pisa was not extended in 1592.

- He quickly found work teaching geometry, mechanics, and astronomy at the University of Padua.

- The timing of the assignment was favorable as Galileo was left in charge of raising his younger brother after his father's death in 1591.

CONTRIBUTION TO SCIENCE

TELESCOPE

- Galileo Galilei heard reports of a Dutch spectacle maker who had created a gadget that made far-off objects appear close while on vacation in Venice in 1609 (at first called the spyglass and later renamed the telescope). A patent had been asked for but had not yet been approved. The techniques were kept a secret because Holland would undoubtedly find great military use in them.

- Galileo Galilei was adamant on building his own spyglass.

- He had never really seen the Dutch spyglass, so for the first 24 frenetic hours of experimenting, he only relied on instinct and hearsay, and he constructed a three-power telescope.

- He carried a 10-power telescope to Venice after considerable polishing, where he wowed the Senate by showing it off.

- His pay was swiftly increased, and he received proclamations in his favour.

- Along with building the telescope and making a number of other mathematical and scientific breakthroughs, Galileo also built a hydrostatic balance in 1604 to measure tiny items. He also devised the universal rule of acceleration, which all objects in the cosmos followed, and improved his theories on motion and falling objects during the same year. He also came up with a basic thermometer.

DISCOVERY AND OBSERVATIONS

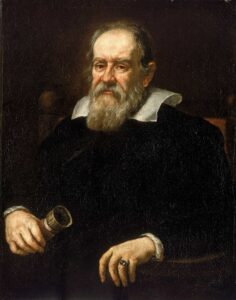

- Galileo Galilei might only have been a minor footnote in history if he had stopped here and gone on to become a wealthy and affluent man. Instead, a revolution was sparked when the scientist pointed his telescope towards the moon, which everyone at the time assumed to be a flawless, smooth, polished celestial orb.

- Galileo Galilei was amazed to see an uneven, rough, surface, full of holes and prominences. Many individuals believed Galileo Galilei was mistaken, including a mathematician who believed that even if Galileo had observed a rough surface on the moon, the moon must actually be entirely coated with smooth, translucent, invisible crystal.

- As the months went on, his telescopes got better. He discovered three tiny, brilliant stars close to Jupiter on 7 January 1610, using his 30-power telescope. Three of them were in a straight line; two were to the east and one was out to the west. The following evening, Galileo once more observed Jupiter and noticed that all three of the "stars" were still in a straight line but were now west of the planet.

- Galileo was forced to come to the unavoidable conclusion after weeks of observations that these tiny "stars" were actually tiny satellites orbiting Jupiter. The Earth might not be at the centre of the universe if there were satellites that didn't orbit the planet. Could it not be true that the sun is at the centre of the solar system, as proposed by Copernicus?

- In March 1610, amid a great deal of popular praise and excitement, Galileo Galilei published his discoveries in a little book named "The Starry Messenger," of which 550 copies were made. The majority of Galileo's papers, all of which were published in Tuscan, were only in Latin.

Diagram of the Moon

THERMOMETER

- Galileo did not create the straightforward glass-bulb thermometer known as a Galileo thermometer; rather, he understood that the temperature of a liquid affects the liquid's density. Modern thermometers are comparable to the thermoscope that Galileo created (or assisted with the creation of). The temperature of the liquid causes it to rise or fall in a glass tube within the thermoscope.

CONFLICT WITH THE CHURCH

- The Copernican hypothesis, which holds that the earth and planets rotate around the sun, was openly supported by Galileo after he constructed his telescope in 1609. However, the Aristotelian teaching and the established order established by the Catholic Church were both called into question by the Copernican hypothesis. In a letter to a pupil in 1613, Galileo argued that the Copernican hypothesis did not conflict with biblical texts since the Bible was written from an earthly perspective, and that science offered a more correct perspective.

- Following the letter's release to the public, Church Inquisition advisors declared Copernican doctrine to be heretical. Galileo received a directive not to "hold, teach, or defend in any form" the Copernican hypothesis in 1616. For seven years, Galileo followed the directive, partly out of convenience and partially because he was a devout Catholic.

- When Cardinal Maffeo Barberini, a close friend of Galileo, was elected Pope Urban VIII in 1623, he urged Galileo to publish his work on astronomy and permitted him to continue it—but only if it was impartial and did not support Copernican doctrine. Galileo was inspired to write ‘Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems’, which supported the hypothesis, in 1632.

- The response from the church was prompt, and Galileo was invited to Rome. From September 1632 until July 1633, Galileo was the subject of Inquisition proceedings. Galileo was generally treated with respect at this period and was never imprisoned.

- Galileo was ultimately coerced into admitting he had backed the Copernican hypothesis by threats of torture, although he still believed his remarks to be true in private.

- He was found guilty of heresy, and the rest of his life was spent under house imprisonment.

- He disobeyed orders not to have any visitors and not to have any of his works published outside of Italy.

- His study of forces and their effects on matter was translated into French and published there in 1634.

- A year later, copies of the Dialogue were also printed in Holland.

- Galileo composed ‘Two New Sciences’, which was published in Holland in 1638, when he was under house arrest.

- Galileo was ill and had lost his sight by this point.

- But eventually, the Church was unable to refute scientific reality.

- It ended the embargo on the majority of writings endorsing Copernican theory in 1758.

- The Vatican didn't completely abandon its objection to heliocentrism until 1835.

- Several popes recognised Galileo's outstanding contributions over the 20th century, and in 1992, Pope John Paul II expressed remorse over the way the Galileo matter had been handled.

DEATH AND LEGACY

- On 8 January 1642, Galileo Galilei passed away in Arcetri, Italy. When he passed away, he was 77 years old. In his latter years, Galileo had experienced a number of health problems, including kidney stones and heart illness, which most certainly contributed to his demise. Up until the time of his passing, he worked on several scientific initiatives despite his deteriorating health.

- With Galileo's passing, a great life that changed the course of history came to an end. His contributions to the disciplines of mathematics, physics, and astronomy are still honoured and studied today, making him one of the most significant personalities in the history of science. Numerous generations of scientists and academics have been inspired by the life and work of Galileo, and his impact has endured across the world.

Galileo’s Tomb - Galileo Galilei was a groundbreaking figure in the history of science, and his impact and inspiration may still be felt today. He received widespread acclaim for his work in the disciplines of mathematics, physics, and astronomy as well as for establishing the scientific method and the empirical approach to scientific research. The four biggest moons of Jupiter were discovered by Galileo, who also invented the first telescope and conducted significant astronomical studies that contributed to the development of the heliocentric theory of the solar system.

- In addition, he made substantial contributions to the disciplines of mathematics and physics, such as the invention of kinematics and the law of falling bodies. Galileo, who cleared the ground for the scientific revolution by challenging conventional Aristotelian ideas, had a profound impact on a great number of researchers and scientists, including Isaac Newton and Johannes Kepler. He is now regarded as the founder of modern science and one of the most significant individuals in the development of science. Future generations of scientists and philosophers are still inspired by him.