Glorious Revolution Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the Glorious Revolution to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Background of the Revolution

- James II of England

- William III of Orange

- The Bill of Rights and the Parliament

- Legacy of the Glorious Revolution

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about the Glorious Revolution!

Between 1688 and 1689, England saw the Glorious Revolution, famously known as the Bloodless Revolution and the Revolution of 1688. James II, a Catholic, was overthrown, and Mary, his Protestant daughter, and her Dutch husband, William of Orange, took James’ place. The revolution’s causes were multifaceted and comprised both political and theological considerations. The incident ultimately altered England’s system of government by giving Parliament more control over the Crown and sowing the seeds of democracy.

BACKGROUND OF THE REVOLUTION

- James was crowned king in 1685 with widespread support despite his Catholicism, as seen by the swift suppression of the Argyll and Monmouth Rebellions. Less than four years later, he was sent into exile. Modern historians contend that James was unaware of how heavily his kingdoms’ landed gentry — the vast majority of whom belonged to the Protestant Church of England and Church of Scotland — depended on him for support, even though this event was frequently perceived as being wholly an English phenomenon.

- Despite a willingness to accept his personal Catholicism, his supporters in England and Scotland were in the end alienated by his ‘tolerance’ policies and strategies for overcoming opposition. In Ireland, which had a majority of Catholics, they even caused unrest.

- James VI and I, who in 1603 had envisioned a centralised state governed by a monarch whose authority came from God, and whose Parliament’s only role was to obey, was the originator of the Stuarts’ political doctrine. The War of the Three Kingdoms was caused by disagreements over the monarch’s relationship with Parliament, which persisted even after the Stuart Restoration in 1660.

Charles I in Three Positions, a 1633 painting by Anthony van Dyck, is the monarch of the Three Kingdoms.

THE WAR OF THE THREE KINGDOMS

Between 1639 and 1651, England, Scotland and Ireland — three independent kingdoms ruled by the same king, Charles I — were the scene of several interrelated wars that included invasions, civil wars, and uprisings. The most famous of these is the English Civil War.

- Most individuals who supported James in 1685 in England and Scotland intended to keep the current political and religious structures, but this was different in Ireland. Although he was sure to have the backing of the Catholic majority, James was also well-liked by Irish Protestants since the Church of Ireland needed royal support to survive.

The Political Background in England

- James’s followers rejected his ‘tolerance’ ideas, which would have allowed Catholics to assume public office and participate in public life, even if they believed that hereditary succession was more significant than his Catholicism. Devout Anglicans, who claimed that the measures he proposed conflicted with his oath as king to defend the authority of the Church of England, spearheaded the opposition.

- In an era when oaths were essential to a healthy community, James was seen as breaking both his and others’ promises by insisting on Parliament’s acceptance of his conduct. Despite being ‘the most Loyal Parliament a Stuart ever had,’ Parliament refused to comply.

- Although most historians agree that James wanted to advance Catholicism rather than create an absolute monarchy, his obstinate and rigid response to criticism had the same effect.

- He governed by decree in November 1685 when the English and Scottish Parliaments failed to abolish the 1678 and 1681 Test Acts. It was strategically foolish to organise a ‘King’s party’ of Catholics, English Dissenters and dissident Scottish Presbyterians because it would have rewarded those who took part in the 1685 uprisings and marginalised his followers.

- It was likewise inappropriate to demand Catholic tolerance at this time. Following the 1598 Edict of Nantes revocation, which had granted French Protestants the freedom to practise their religion, by Louis XIV of France in October 1685, an estimated 200,000 to 400,000 people fled France over the following four years, with 40,000 of them settling in London.

Timeline of events: 1686 to 1688

- Most people who supported James in 1685 did so because they desired stability and the rule of law, which were regularly threatened by his behaviour.

- The premise of his attempt to rule by decree after suspending Parliament in November 1685 was uncontested. Still, the expansion of its reach raised serious concerns, especially when judges who disagreed with its application were fired.

- His political bumbling frequently made matters worse. The Ecclesiastical Commission of 1686, intended to punish the Church of England and include suspected Catholics like the Earl of Huntingdon, infuriated everyone.

- In April 1687, he ordered Magdalen College, Oxford, to nominate a Catholic sympathiser called Anthony Farmer as president. Still, because he was ineligible under the college rules, the fellows elected John Hough in his place.

- On 24 August 1688, writs for a general election were issued. The military’s expansion caused great concern, particularly in England and Scotland, where the Civil War left a lasting aversion to standing armies.

- In April 1688, he ordered his Declaration of Indulgence to be read in every church. When the Archbishop of Canterbury and six other bishops refused, they were charged with seditious libel and imprisoned in the Tower of London.

- Talbot had replaced Protestant officers in Ireland with Catholics, and James did the same in England.

- The acquittal of the Seven Bishops on 30 June undermined James’s political power, while the birth of James Francis Edward Stuart on 10 June raised the possibility of a Catholic monarchy.

JAMES II OF ENGLAND

- During the brief reign of King James II, which spanned from 6 February 1685 to 11 December 1688, England quickly discovered what sort of nation it had been in the past and what kind of nation it aspired to be in the future. The Divine Right of Kings and King James II’s ideas on Protestantism vs Catholicism would finally pave the way for a spectacular but bloodless revolution in 1688. In 1685, when King James II of England ascended to the throne, tensions between Catholics and Protestants were high, and the monarchy and the British Parliament also had a great deal of conflict.

- Around the time of James II’s assumption to the throne in 1685, the relationship between Catholics and Protestants in England became more strained. Being a Catholic himself, King James allowed freedom of religion, especially for the Catholics, and even favoured them to hold an office, like military positions. In March 1687, the King issued the controversial Royal Declaration of Indulgence, which suspended all laws concerning the punishment of Protestants who rejected the Church of England.

- In 1687 James II dissolved Parliament and attempted to establish a new one which would not oppose him with respect to the Divine Right of Kings, a doctrine of absolutism that he insisted on during his reign.

- At that time, James’s Protestant daughter, Mary II, was the only rightful person in the royal line of succession. However, this situation changed when the King had a son in 1688, whom he vowed to raise as a Catholic.

- For such reason, the Protestant population of England feared that this would result in a Catholic dynasty in the country, which eventually caused the revolution.

WILLIAM OF ORANGE

- In 1677, Mary II, James’s daughter, married her first cousin, Prince William III of Orange, a sovereign principality that is now under southern France.

- William played a crucial role in ousting James II and preventing his Catholic-driven rule. He had already planned to invade England but decided not to do so without firm inside support from England itself.

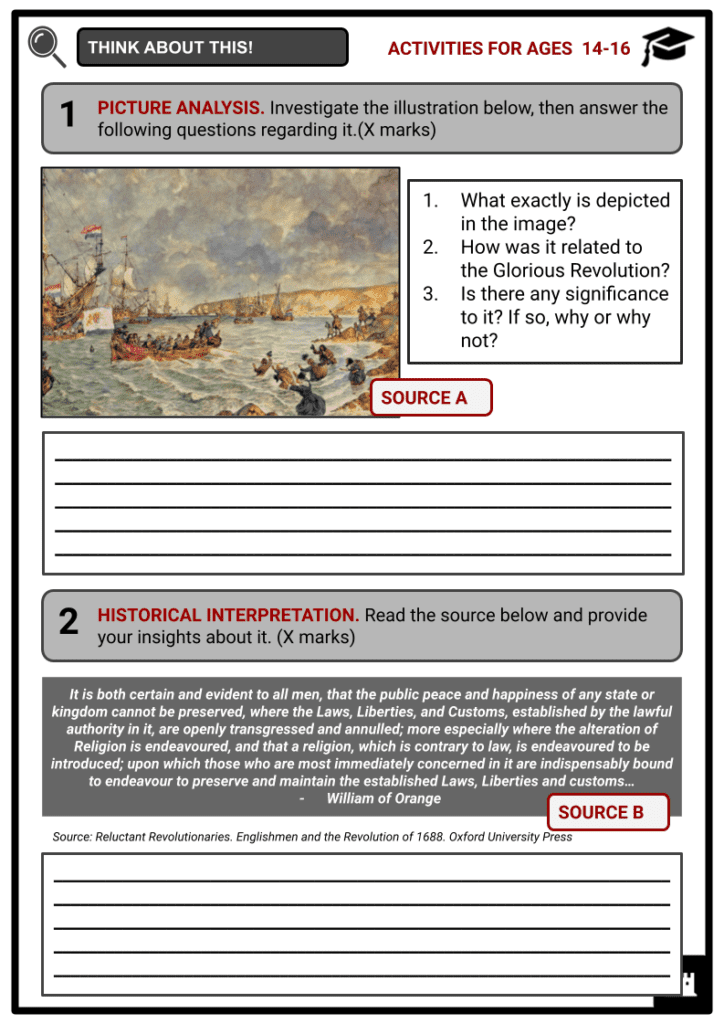

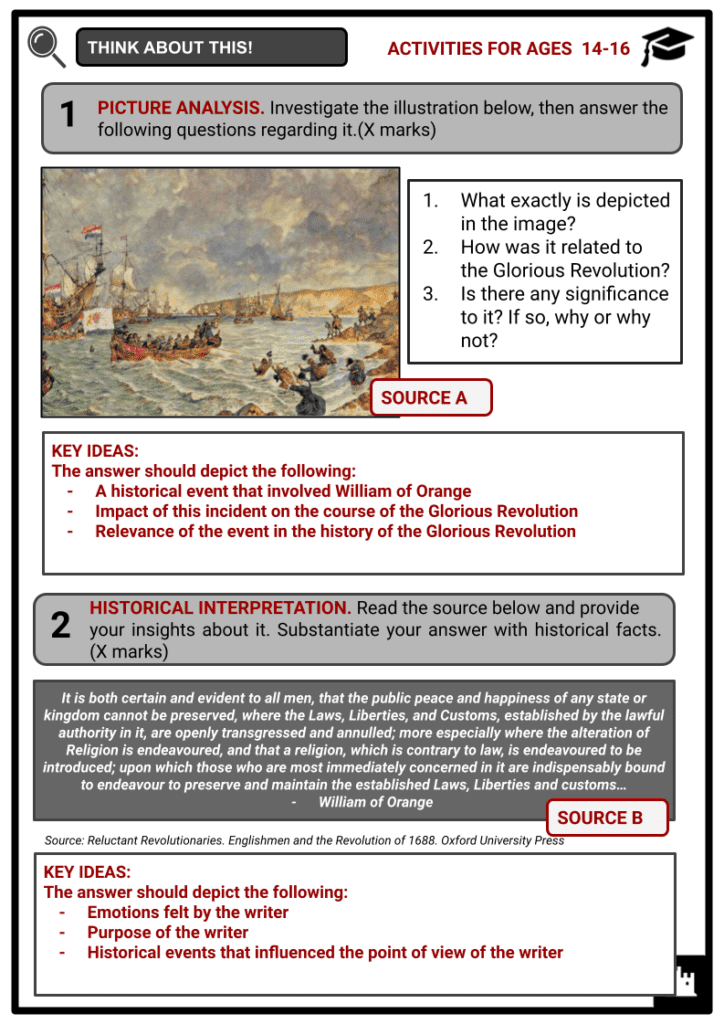

- Support came in April 1688 when seven of James’s peers wrote a letter to William as a pledge of allegiance to him to invade England. Following this, William III prepared a naval armada which landed in Torbay, Devon, in November 1688.

Painting of William and Mary on the ceiling of the Painted Hall by Sir James Thornhill - The King, aware of the invasion in the interim, prepared his men, who departed London to confront the advancing armies. However, several of James’s supporters — including some of his family — turned against him and joined with William.

- James II relocated to London on 23 November 1688 due to this setback and deteriorating health.

- James consented to a freely chosen Parliament and promised universal pardon to all rebels who intended to flee England.

- James successfully disbanded his armed force in December 1688 and escaped to France, where he eventually perished in exile in 1701.

THE BILL OF RIGHTS AND THE PARLIAMENT

- A split English Convention Parliament gathered in January 1689 to transfer the thrones of England, Scotland and Ireland.

- The Radical Whigs, a powerful political organisation whose members advocated a constitutional monarchy and were vocal opponents of James’s absolute monarchy, recommended that William III take the throne as an elected king, implying that his power would come from the people.

- Another political faction contended that Mary II should be Queen and William should be her regent.

- Parliament eventually reached a compromise and agreed to a joint monarchy with William III as King and James’s daughter, Mary II, as Queen.

- Furthermore, the compromise agreement also included that William and Mary should sign An Act Declaring the Rights and Liberties of the Subject and Settling the Succession of the Crown, more commonly known as the English Bill of Rights. They signed the bill in February 1689.

- The bill lays out specific constitutional criteria for the Crown to get the people’s agreement as represented in Parliament, most of which are based on the theories of political theorist John Locke.

- Along with limiting the monarch’s power, it created the rights of Parliament, including regular parliaments, free elections and freedom of speech.

- Additionally, it listed people’s freedoms, such as the right not to pay taxes charged without parliamentary authorisation and the ban on cruel and unusual punishment. Finally, it recorded and denounced several of James II of England’s transgressions.

- The Magna Carta attracted new attention in the 17th century. The English Parliament adopted the Petition of Rights, establishing several subjects’ privileges in 1628.

- The New Model Army Grandee and modest, leveller-influenced personalities debated a new constitution in the Putney Debates of 1647, during which the idea of long-term political parties took shape. The English Civil War pitted the King against an elected but oligarchic Parliament (1642–1651).

- During the Protectorate (1653–1659) and most of the 25 years of Charles II'’s English Restoration, the administration primarily frightened Parliament (1660–1689).

- However, it was able to restrain some of the executive excess, intrigue and generosity of the government, particularly the Cabal ministry, which signed a Secret Treaty of Dover that allied England to France in a potential war against frequent allies, the Netherlands.

- The rise in printed pamphlets and assistance from the City of London made this possible. It had already approved the Habeas Corpus Act in 1679, which tightened the rule prohibiting imprisonment without a valid reason or body of proof.

- The Bill of Rights 1689, an Act of Parliament, which obtained the Royal Assent in December 1689, enacted the Declaration of Rights.

- It is forbidden for regal authority to purport to suspend or repeal legislation without the approval of Parliament;

- It is unlawful to have the commission for ecclesiastical causes;

- Taxation without parliamentary authorisation is prohibited;

- The right to petition the monarch belongs to the people, and doing so is against the law;

- It is against the law to maintain a standing army during times of peace unless approved by Parliament;

- Protestants may possess weapons for self-defence appropriate to their circumstances and permitted by law.

LEGACY OF THE GLORIOUS REVOLUTION

- Many historians believe that the Glorious Revolution was a crucial turning point in Britain’s journey from an absolute to a constitutional monarchy. The monarchy in England would never again have complete control following this incident.

- The regent’s power was first defined, recorded and constrained by the Bill of Rights. In the years following the revolution, Parliament’s role and influence underwent a significant transformation.

- The 13 North American colonies were impacted by the incident as well. After King James was deposed, the colonists were temporarily exempt from stringent, anti-Puritan legislation. Once word of the revolution reached the Americans, various uprisings occurred, including the Boston Revolt, Leisler’s Rebellion in New York, and the Protestant Revolt in Maryland.

- Since the Glorious Revolution, Parliament’s authority in Britain has grown steadily while the monarchy’s hold on the country has diminished. Undoubtedly, this significant event played a role in creating the political environment and current government of the United Kingdom.

- The Glorious Revolution had a negative social and political impact on English Catholics. Catholics were prohibited from voting, holding elected office or holding commissioned military positions for more than a century.

- The revolution freed the Protestant Puritans in the American colonies from many onerous regulations imposed by Catholic King James II.

- Perhaps most significantly, the Glorious Revolution provided the foundation for constitutional law that established and defined governmental authority and set forth how rights were granted and curtailed.

- The constitutions of England, the US and many other Western countries all incorporate these principles for dividing powers and responsibilities among the clearly defined executive, legislative and judicial branches of government.