Kett's Rebellion Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Kett's Rebellion to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Background

- Account of the rebellion

- Aftermath of the rebellion

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about Kett's Rebellion!

During the reign of Edward VI of England, land enclosures turned out to be a burden to the villagers, pushing them to rise against the local landowners. Kett’s Rebellion took place in Norwich in July-August 1549. Robert Kett, who was one of the targets of the rising, decided to join and lead the peasants in destroying fences that had been put up by wealthy landowners, including his own. The rebel forces grew as they set off for Norwich, which eventually fell to them. The royal army under the command of the Earl of Warwick defeated them, leading to the deaths of thousands and the execution of Kett and hundreds of rebels.

Background

- During the early 1500s, an agricultural crisis emerged in England, resulting in outbreaks of unrest across the country. Kett's Rebellion in Norfolk was the most alarming of these.

- As the majority of the population depended on the land, many were affected by the crisis that resulted from land enclosure.

- A considerable number of farmers shifted from growing crops to raising sheep, which at the time became much profitable owing to the increase in demand for wool.

- Enclosure followed, with local landowners fencing arable land and turning it into pasture for sheep for their own use.

- The enclosing of common land that had been used by the villagers for hundreds of years left them with nowhere to graze their animals.

- Apart from this, the common people were burdened by the following:

- Inflation

- Unemployment

- Rising rents

- Declining wages

- Religious reforms

- Many people were angered by these difficulties, leading villagers to begin tearing down the fences that had been used to enclose the common land.

- As enclosure enabled landowners to gain great wealth by selling wool, peasants and yeoman farmers found it hard to survive with the lack of common land for farming and raising animals.

A medieval illustration of men harvesting - During the reign of Henry VIII, Thomas Crowell attempted to manage the problem brought about by enclosure by attempting to limit the number of sheep which owners were allowed to keep. However, this had little impact on the situation.

- In March 1549, an act was passed, imposing a poll tax upon sheep on the assumption that landowners would hardly convert their land from arable to pasture due to heavy taxation.

- Rebellion and riots began to take place all over the country. The young Edward VI was the reigning monarch at the time.

Account of the rebellion

- In April 1549, the Lord Protector, Duke of Somerset, issued a proclamation against enclosures, declaring that landlords would be forced to take down hedges and fences enclosing the land. This convinced rioters that they were acting legally.

- In June, spontaneous uprisings broke out in Devon and Cornwall.

- Fences built by the lord of the manor were torn down. These outbreaks were quickly put down.

- By July, a group of people set off to the villages of Morley St Botolph and Hethersett to tear down hedges and fences.

- Sir John Flowerdew, an unpopular local landowner, was one of the first targets of the rioters. He was able to bribe the rebels to leave his enclosures alone and instead attack those of Robert Kett at Wymondham.

- Robert Kett was a wealthy landowner, whose family had been farming in Norfolk. Unlike Flowerdew, he had been prominent among the parishioners for interfering when Wymondham Abbey was demolished. When the rioters arrived at his estates, he listened to their grievances and subsequently decided to join their cause.

- Kett joined the rioters in tearing down his own fences. After that, they went back to Hethersett to attack Flowerdew’s enclosures.

- With Kett now as their leader, the rebels set off for Norwich and soon, people from nearby towns and villages enlisted to their cause.

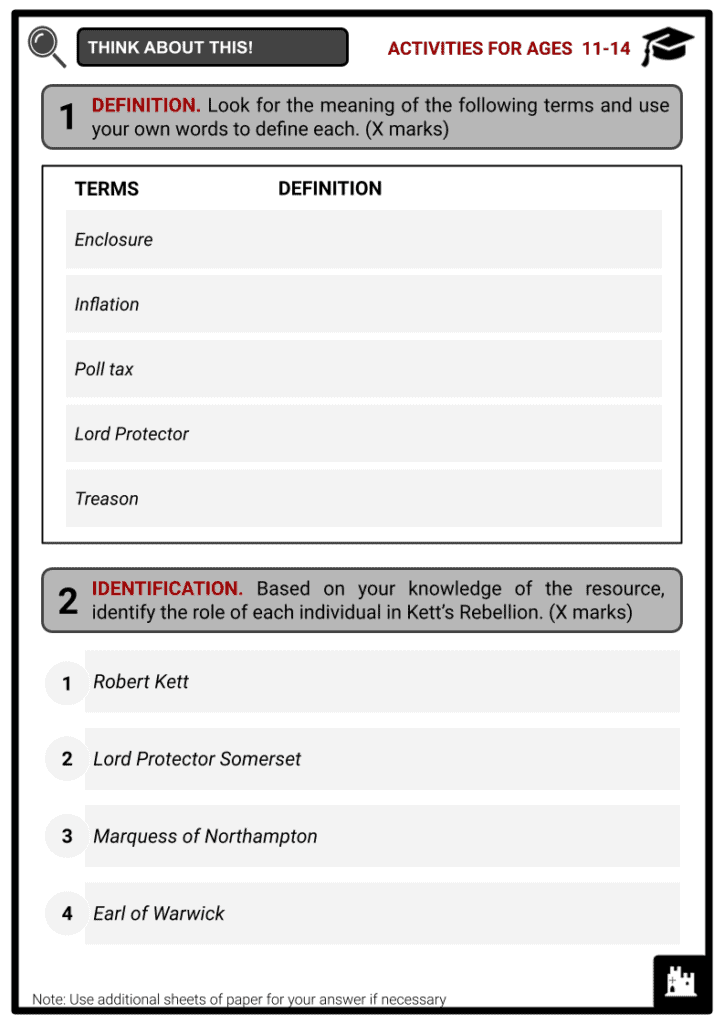

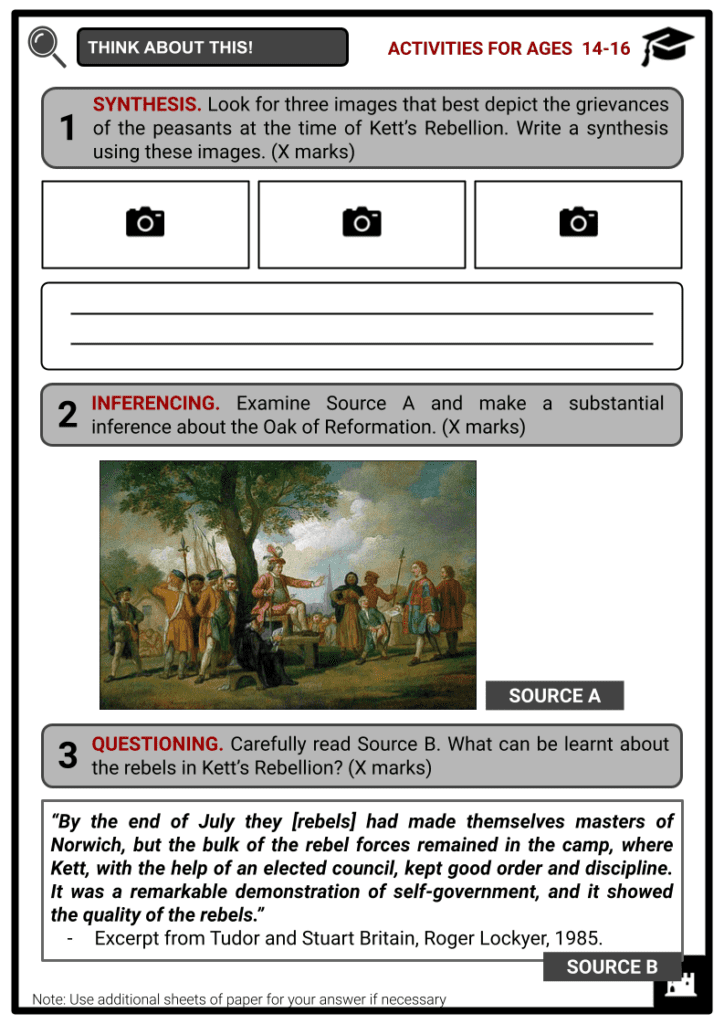

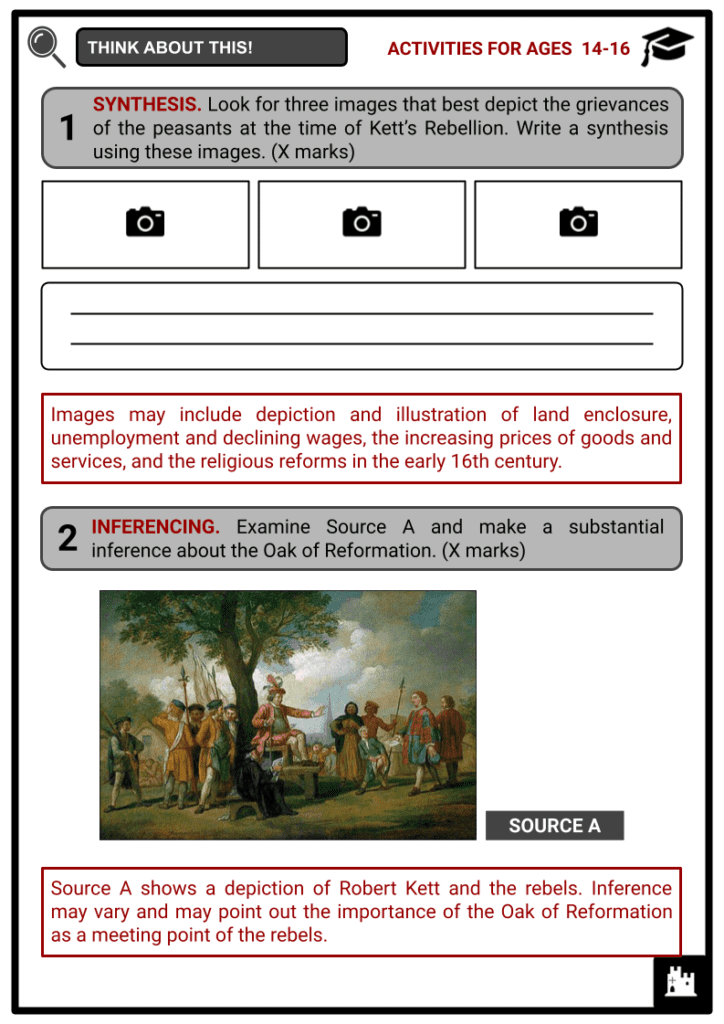

Norwich at the time of Kett’s Rebellion - With the rebels now numbered several thousands, the city authorities refused them entry to Norwich. As a result, the rebels camped at Mousehold Heath just outside the walls of the city. Known as the “Oak of Reformation”, an oak tree on the road between Wymondham and Hethersett became the meeting point of the rebels.

- Mousehold provided the rebels a vantage point overlooking Norwich, becoming their base for the succeeding weeks. Kett set up his headquarters in St Michael’s Chapel. He met with his council comprised of representatives from the Hundreds of Norfolk and one representative from Suffolk. The camp further swelled, with the number of the rebels rising to 16,000.

- Whilst in camp, Kett and the rebels drew up a list of 29 grievances: only one of these articles mentioned enclosures. They sent it to Lord Protector Somerset.

- By 21 July, a messenger from the king’s council arrived at Norwich from London bearing the council’s order that the rebels would not be allowed to enter the city. Furthermore, a pardon was offered if the gathering were to disperse. In response, Kett rejected the offer and began an attack on Bishopsgate Bridge.

- The messenger retreated into Norwich with the mayor. Meanwhile, the rebels charged down from Mousehold and began swimming the River Wensum. They were not stopped by the city defenders and Norwich quickly fell to the rebels. Another pardon was offered to the rebels which was again rejected. Several city officials were held in the rebel camp. Military supplies were taken by the rebels.

- To suppress the rebellion, the king’s council sent about 1,400 men under the leadership of the Marquess of Northampton. The royal army was initially successful in driving off the rebels but was soon beaten under Kett's command. With the loss of a senior commander, Northampton ordered his troops to retreat.

- A larger and stronger army of around 14,000 men under the command of the Earl of Warwick was then sent to Norwich. Warwick, an experienced and prominent leader, managed to enter the city on the 24th of August by attacking the St Stephen’s and Brazen gates. The rebels retreated through the city and set fire to houses in an attempt to slow the royal army’s advance.

A 19th-century depiction of Mousehold Heath - By afternoon, Warwick’s baggage train, which held all the artillery, entered the city, continuing through Tombland and straight down Bishopsgate Street towards the rebel army. A group of rebels tried to capture it.

- On 25 August, the rebels began an artillery attack on the walls around the northern area of the city and were able to gain control of it. With the north of the city again in rebel hands, Warwick responded with an attack.

- On 26 August, around 1,400 foreign mercenaries arrived in the city. This provided Warwick with a formidable army to suppress the rebels. When Kett and the rebels became aware of this, they left their camp at Mousehold that night for lower ground in preparation for battle.

- On 27 August, the opposing armies faced each other and the final battle began at Dussindale, a small valley outside the city. Although the rebels outnumbered the royal army, their lack of cavalry enabled their defeat by Warwick’s well-armed and trained troops. Thousands of rebels were killed, whilst the royal army lost some 250 men.

Aftermath of the rebellion

- On 28 August, around 30 to 300 rebels were hanged at the Oak of Reformation and outside the Magdalen Gate in addition to the 49 rebels executed by Warwick’s men a few days before. Meanwhile, a day after the final battle, Kett was captured a few miles from the site. He and his brother William Kett were then taken to the Tower of London to await trial for treason.

- Kett twice refused a pardon and was found guilty of treason. He was hanged at Norwich Castle on 7 December.

- On the same day, William was hanged from the west tower of Wymondham Abbey.

- Kett’s corpse was left hanging long after his death, to serve as a warning to the people of Norwich.

- Following the rebellion, Lord Protector Somerset, who was sympathetic to the rebel cause, found himself removed from power. He was criticised for the poor handling of the uprising.

- He was held briefly at the Tower of London, and deprived of a portion of his estates. He was restored to the council only to be sent to the Tower again in 1551. In 1552, he was executed for felony.

- Meanwhile, the Earl of Warwick became Somerset’s successor in early 1550.

- Enclosures continued to be unchecked for many years after the rebellion. As the price of wool continued to rise, more common land and arable fields were converted to sheep pasture.

- By the 19th century, Robert Kett began to be viewed as a folk hero. On the 400th anniversary of Kett’s Rebellion in 1949, the city of Norwich put up a plaque at the scene of the executions. In 1999, a memorial to Kett, who by then was considered a symbol of the struggle for basic human rights, was placed in Wymondham.

Image Sources

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/fb/A_group_of_dissenters_in_Norfolk_during_Robert_Kett%27s_rebellion_of_1549.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/61/Reeve_and_Serfs.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/thumb/e/ec/Norwich_at_the_time_of_Kett%27s_Rebellion.jpg/800px-Norwich_at_the_time_of_Kett%27s_Rebellion.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/ab/Mousehold_Heath%2C_Norwich%2C_by_John_Crome.jpg/1024px-Mousehold_Heath%2C_Norwich%2C_by_John_Crome.jpg