Nine Years' War Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the Nine Years' War to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Occurrence prior to the Nine Years’ War

- The War and the Nations and Empires Involve

- The Peace and Impact of the War

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about the Nine Years' War!

The Nine Years’ War (1688–1697), commonly referred to as the War of the Grand Alliance, was a war between France and a group of European nations that mostly consisted of the Holy Roman Empire (headed by the Habsburg monarchy), the Dutch Republic, England, Spain, Savoy, and Portugal. It was a power battle between Louis XIV of France and William III of Britain that developed because of French aggression in the Rhineland.

Occurrence prior to the Nine Years’ War

- Before the occurrence of the Nine Years’ War, there was a Franco-Dutch War happened around 1678–1687 when Louis XIV of France, who was at the height of his power, attempted to forcibly impose religious harmony in France as well as secure and enlarge his borders.

- Louis XIV of France had already achieved personal glory through the conquest of new lands, therefore he was no longer inclined to continue his open-ended militarist programme from 1672. Instead, to accomplish specific strategic goals along his borders, he would rely on France's undeniable military supremacy.

- A more mature Louis proclaimed the "Sun King," had switched from conquest to security by utilising threats, rather than open battle, to subdue his neighbours. He was aware that he had failed to accomplish decisive results against the Dutch.

- Around 1687–1688, the League of Augsburg had little military power that included the Empire and its allies in the form of the Holy League who were still busy fighting the Ottoman Turks in Hungary in that period.

- The dread of French reprisals made many of the small princes hesitant to take any action. Leopold I's advances against the Ottomans, however, were something Louis XIV was wary of.

Louis XIV of France - Louis XIV and his ministers had anticipated for a speedy settlement like the one obtained from the War of the Reunions, but by 1688 the circumstances had significantly changed.

- While William of Orange was quickly emerging as the head of a coalition of Protestant nations in the west and north, an Imperial army had destroyed Imre Thököly's insurrection in Hungary and eliminated the Turkish menace in the east.

- By crossing the Rhine that summer, Louis started a long war of attrition that was framed by the interests of the state, its defended borders, and the balance of power in Europe even if he had only intended to wage a brief defensive war.

The War & the Nations and Empires Involved

- From 1688 to 1697, the Nine Years’ War began to rise where British soldiers formed a European coalition to oppose French expansionism. At the same time, there was fierce warfare between James II's supporters and those of King William III in Scotland and Ireland.

- The War in Scotland and Ireland

- In 1688, after King William III gained the throne during the Glorious Revolution, he set out to fight the forces of his exiled adversary, James II, in Scotland and Ireland.

- After fleeing to France, James II appointed John Graham of Claverhouse, Viscount Dundee, as the leader of his soldiers in Scotland.

- Dundee assembled an army of Highlanders in the spring of 1689 to confront the troops of the newly installed Williamite authority.

- After months of unsure maneuvering, he attacked and routed General Hugh Mackay's government forces in the pass of Killiecrankie on 27th of July.

- Dundee, on the other hand, perished in the attack. Although the Jacobite army got reinforcements at Blair, his passing significantly decreased its efficacy.

King James II - On 18 August 1689, the Jacobites, also known as James' supporters, advanced further south and attacked Dunkeld. A single regiment, freshly created from a fanatical group of Covenanters known as Cameronians, held the town. The Jacobites were forced to retreat after a four-hour battle, and the clans split up.

- After an unsuccessful uprising in 1690, Mackay marched through the Highlands with 6,000 troops and started building Fort William at Inverlochy to restore order.

- In March 1689, James II arrived in Ireland. He hoped to use it as a base to retake the throne of England.

- In Ireland, the conflict that was raging throughout Europe was reflected in the makeup of the opposing forces. The Jacobite side was supported by large French contingents, while William's army was comprised of Irish, English, Dutch, Danish, and German soldiers.

- The Sieges and William’s Main Army

- Richard Talbot, Earl of Tyrconnel, succeeded in limiting Williamite support to the beleaguered towns of Londonderry and Enniskillen using the regular Irish battalions he had commanded with Catholics a few years previously. Up until Major-General Percy Kirke rescued the town in August 1689, Londonderry had been under siege for three months.

- The defenders stubbornly held on, but they lacked aggression and allowed themselves to be surrounded by fewer Jacobites. On the other hand, the Enniskillen defence mounted a valiant offencive throughout 1689, using the town as a base to engage the attackers. They frequently routed more powerful Jacobite forces and successfully defended the towns of Ballyshannon and Belleek, allowing them to receive supplies by ship.

- Under the vigorous leadership of Colonel Thomas Lloyd, his cavalry conducted many raids to replenish their supplies and throw the Jacobites off guard.

- A seasoned German general named Marshal Frederick Duke of Schomberg led William's main army as it arrived at Carrickfergus in August 1689. Schomberg was only able to hold a bridgehead due to a lack of supplies and the immaturity of many of his English soldiers. In the army's Dundalk fall camp, many of his soldiers perished.

- In order to take control of the fight the following June, William personally descended on Carrickfergus and brought with him seasoned reinforcements. James fled in front of him as he moved southward in opposition.

- At the Boyne and Aughrim

- On 1 July 1690, the Boyne River near the town of Drogheda was the site of an attempt by the Jacobites to hold a position. Despite having a large cavalry contingent, William's army outnumbered James' and lacked efficient artillery.

- Since the river could be bridged, William was able to outflank the Jacobite left and capture many of James' top warriors by using his numerical superiority. When the remaining Williamite soldiers overcame intense resistance and broke through the middle and right of the Jacobite position, James was compelled to retreat.

The death of Frederick, the 1st Duke of Schomberg at the Boyne - William suffered a leg injury in the conflict. The 75-year-old Duke of Schomberg, who served as his second in command, was slain while encouraging his troops during the battle.

- James escaped to France once more after losing. However, his army was able to extend the conflict for another 12 months.

- On 12 July 1691, at Aughrim, it was defeated in one of the deadliest battles ever fought on Irish territory, with about 7,000 men lost. As a result, the Irish Catholic Jacobites' opposition to William was effectively ended.

- To comply with the terms of the peace treaty that put an end to the Irish War of Independence, the town of Limerick resisted James' advances until October 1691.

- The War in Europe

- The greater European war began as a result of King Louis XIV's invasion of the Rhineland in October 1688. He wanted to undermine the dominance of the Holy Roman Empire, which was at the time fighting a bloody war with the Turks and increasing French influence in the German kingdoms. A coalition of France's adversaries in Europe armed itself in reaction.

- French rivalry was primarily with the Holy Roman Empire. The Habsburg family ruled it. Charles II, the Spanish Habsburg emperor, had a lifelong history of ill health and was in critical condition. Without a direct successor, Charles' territories would be inherited by either of his closest dynastic relatives, the Holy Roman Empire's Habsburgs or France's Bourbons.

- In light of the Spanish Habsburg line's impending extinction, part of the reason for the war in Europe was the competition for the position between France and the Empire.

- Grand Alliance and William’s Aim

- William assisted in the formation of the Grand Alliance, which included England, the Dutch Republic, Bavaria, Brandenburg, Saxony, the Holy Roman Empire, Spain, and Savoy when he seized the English crown. It aimed to thwart Louis XIV's future efforts to increase his dynastic and territorial claims in Western Europe.

- The new English king viewed the war as a means of weakening Louis XIV's position of power. In 1672, when the French invaded the Dutch Republic in which William was born, he had organised the resistance. He was also committed to preventing any further attacks.

- Victory in the battle would consequently protect his recently won kingdom, as the French posed a threat to William through their support of the exiled James II.

- War in the Low Countries

- The conflict also spread to the rival nations' foreign territories. During "King William's War," England and France battled alongside their native allies in the Americas. To seize control of the seas, the Anglo-Dutch warships also dealt the French a number of setbacks.

- As one protracted siege followed another, the conflict in the Spanish Netherlands — another territory Louis hoped to acquire — came to a standstill. Major battles were very infrequent and never conclusive enough to put an end to the conflict, despite French successes at Fleurus (1690), Steenkirk (1692), and Landen (1693).

- On 29 July 1693, William attacked the Duke of Luxembourg's French army at Landen, some 30 miles (48 km) east of Brussels, to prevent them from taking control of Brussels and Liege. This was one of the deadliest confrontations of the war.

- William was obliged to retire after a severe battle, but his army was able to do so with some order. Over 25,000 men were lost between the two armies' combined fatalities. Despite winning, the French army sustained such heavy losses that the Duke of Luxembourg was forced to give up his plans for Liege and Brussels.

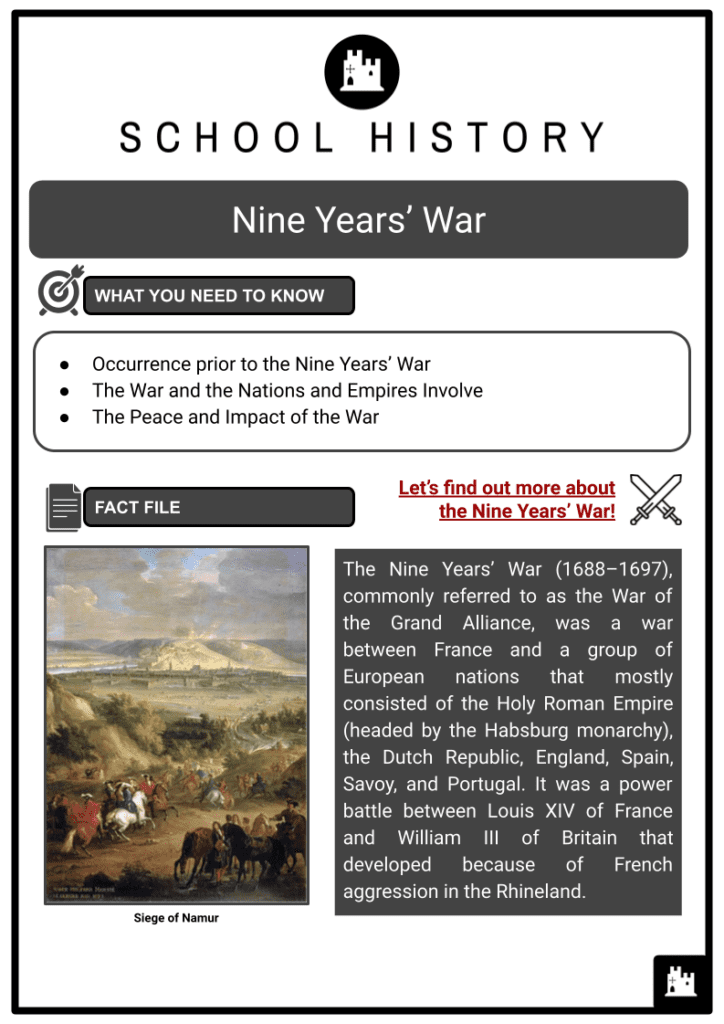

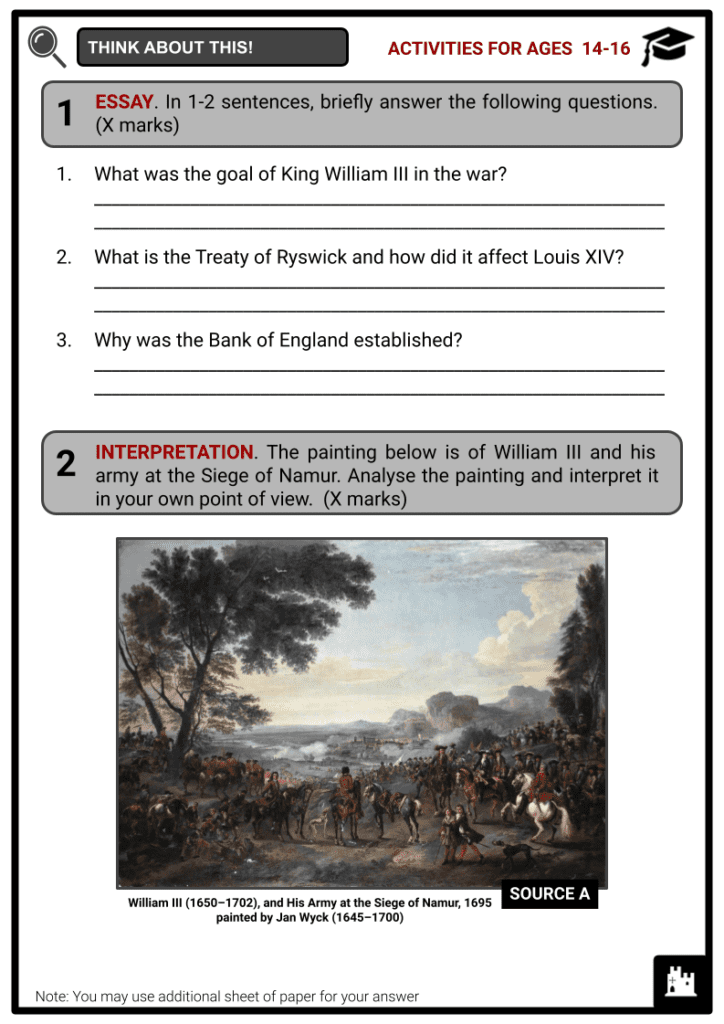

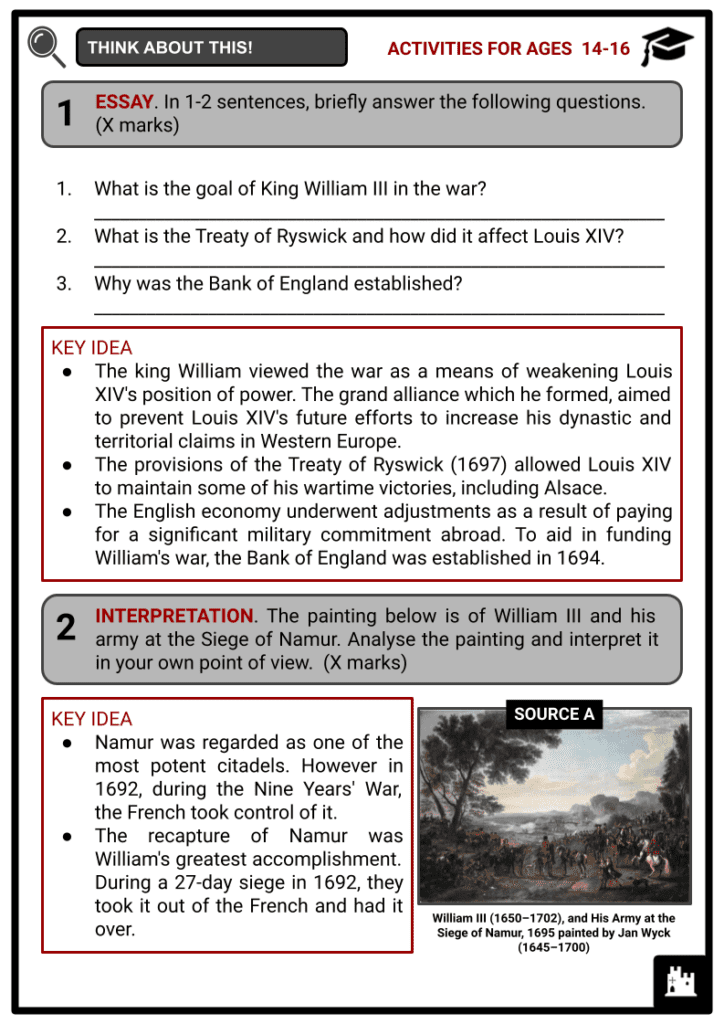

- The recapture of Namur, a city about 35 miles (56 km) southeast of Brussels, was William's greatest accomplishment. During a 27-day siege in 1692, the French had taken control of Namur. Vauban, the renowned military engineer of Louis XIV, then strengthened the city's defences.

King William III and his army at the Siege of Namur - Despite the fact that the citadel was largely regarded as invincible, William's allies besieged it in June 1695 and eventually took it back two months later. On 1 September, the citadel was overthrown after being stormed by the Royal Regiment of Ireland.

- In 1696, all of the battles that Louis XIV's army fought in were favourable to them however, his nation was experiencing an economic crisis.

The Peace and Impact of the War

- In the end, the French mostly won the battle. The extensive battle necessitated a significant increase in troop size. Over 56,000 British soldiers were stationed in the Netherlands by 1697. This time period is where several well-known British regiments got their start.

- Despite their greater military prowess, the French lacked the English and Dutch's financial resources. France was likewise plagued by famine by the middle of the 1690s. The conflict, however, also financially depleted the English and the Dutch. Additionally, everyone was eager for a resolution after Savoy quit the Grand Alliance.

- The provisions of the Treaty of Ryswick (1697) allowed Louis XIV to maintain some of his wartime victories, including Alsace. However, he was driven to abandon his conquests on the east bank of the Rhine and hand back Lorraine to its ruler.

- While the Dutch established a fortification system in the Spanish Netherlands to assist in safeguarding their borders, Louis also recognised William as the legitimate ruler of England.

- The treaty did not, however, address every problem that had led to the conflict. The most crucial issue in modern European politics—the destiny of Spain—remained unanswered. And Louis persisted in his resolve to enlarge his sphere of influence. The War of the Spanish Succession thus resumed fighting in 1701 as a result.

- The army of King William also had a completely different appearance from the ones used during the Civil War (1642–1651). Nearly all pikemen had vanished, and the majority of foot soldiers were now armed with muskets.

- The English economy underwent adjustments as a result of paying for a significant military commitment abroad. To aid in funding William's war, the Bank of England was established in 1694. The National Debt began when the shareholders of the Bank lent money to the government at interest.

Image Sources

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/38/Siege_of_Namur_%281692%29.JPG/300px-Siege_of_Namur_%281692%29.JPG

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/5/5f/Louis_XIV_of_France.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/99/James_II_by_Peter_Lely.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9f/William_III_at_the_Battle_of_the_Boyne.jpg/300px-William_III_at_the_Battle_of_the_Boyne.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/4e/Die_Belagerung_von_Namur_1695.jpg