St. Bartholomew's Day Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about St. Bartholomew's Day to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Definition of Terminologies

- Background of the Event

- Massacres

- Key Participants

- Reactions

- Conclusion

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about St. Bartholomew's Day!

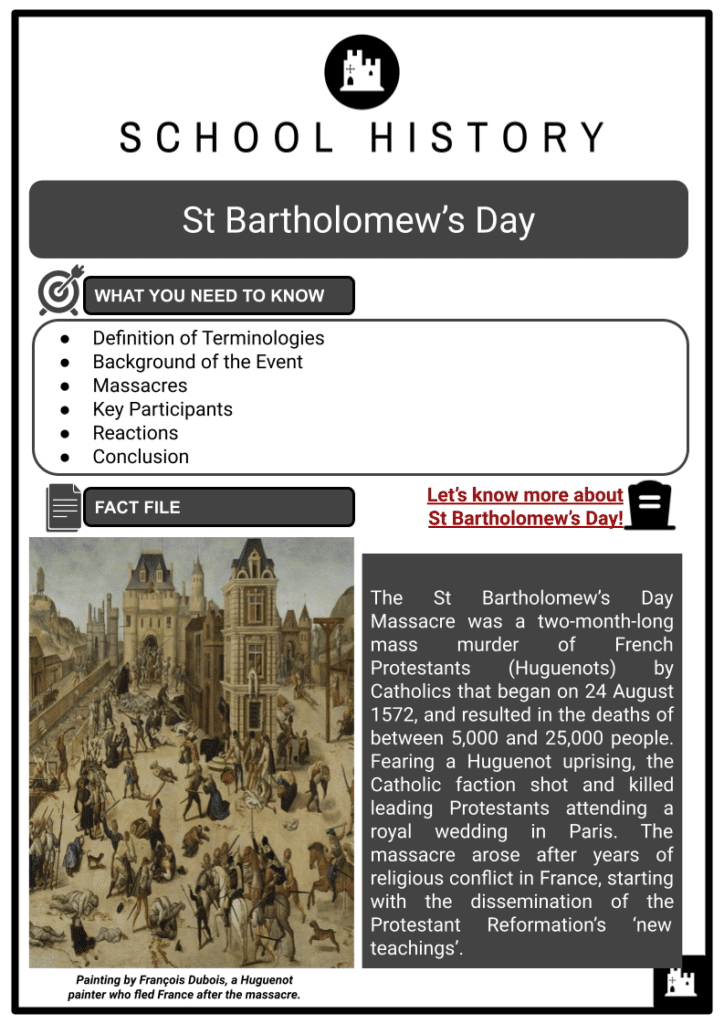

The St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre was a two-month-long mass murder of French Protestants (Huguenots) by Catholics that began on 24 August 1572, and resulted in the deaths of between 5,000 and 25,000 people. Fearing a Huguenot uprising, the Catholic faction shot and killed leading Protestants attending a royal wedding in Paris. The massacre arose after years of religious conflict in France, starting with the dissemination of the Protestant Reformation’s ‘new teachings’.

Definition of Terminologies

- The massacre began on the night of 23–24 August 1572, on the eve of the feast of St Bartholomew the Apostle, two days after Admiral Gaspard de Coligny, the military and political leader of the Huguenots, was assassinated. The slaughter of a team of Huguenot leaders, including Coligny, was ordered by King Charles IX, and it spread throughout Paris.

- The massacre lasted several weeks and spread to the countryside and other urban areas. The number of people killed in France during the massacre ranges from 5,000 to 30,000. In history, the massacre was considered a watershed moment in the French Wars of Religion. Because of the massacre, several prominent aristocratic leaders were killed and the Huguenot political movement was crippled. This unfortunate event led to the conversion of many rank-and-file members to Catholicism.

St Bartholomew (c.1611) by Peter Paul Rubens - Huguenots were French Protestants who followed the theologian John Calvin’s teachings in the 16th and 17th centuries.

- Huguenots fled the country in the 17th century after being persecuted by the French Catholic government during a violent period, establishing Huguenot settlements all over Europe, the United States and Africa.

- St Bartholomew is one of the Twelve Apostles, appearing sixth in the three Gospel lists (Matthew 10:3; Mark 3:18 and Luke 6:14), and seventh in the Acts list (1:13). Bartholomaios is an ancient Hebrew name that means ‘son of Talmai’.

Background of the Event

- Catherine de’ Medici claimed that the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre was unintentional. After all, she was initially involved in a plan to kill only one person rather than thousands. The St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre was the culmination of a series of events.

Peace of St Germain

- On 8 August 1570, the Peace of Saint-Germain-en-Laye was signed, bringing the Third War of Religion to a close. This essentially gave the Huguenots the same rights they had at the start of the war, as well as four ‘security towns’. Despite the fact that the Catholics had managed to win two major battles (Jarnac and Moncontour) during the war, the Huguenots had defended La Rochelle and seized possession of most of the south-west of France. Admiral Coligny had raised a new army in the south before marching up the Rhone to intimidate Paris. On 25 June, he won the war of Arnay-le-Duc, and the Royal Forces’ defeat persuaded Charles IX to make peace.

- Negotiations had been ongoing for the majority of 1570, so a new treaty was quickly agreed upon. Charles IX also agreed to compensate the German reuters who fought for the Huguenots, and to supply them with security towns (La Rochelle, Montauban, La Charité and Cognac) for two years.

- Huguenot leaders such as Condé and Coligny fled court in fear of their lives. Many of their followers were murdered, and the Edict of Saint-Maur revoked Huguenot freedom to worship in September.

Marriage of Henry III of Navarre and Margaret of Valois

- By 1570, Catherine de’ Medici was attempting to arrange a marriage between Margaret and the leading Huguenot, Henry de Bourbon of Navarre (French Calvinist Protestant). The Bourbons were the closest relatives to the reigning Valois family. They were also part of the French royal family, so it was hoped that this union would strengthen family ties and put an end to the French Wars of Religion between Catholics and Huguenots.

Henry of Navarre and Margaret of Valois - The marriage was not a love match, but rather a state affair intended to end more than ten years of religious civil wars in France.

- Margaret was a reluctant bride, and legend has it that when she did not respond to the question of marriage, her brother King Charles IX pushed her crown, causing her head to nod ‘yes’.

- The celebrations continued for three days, but despite the marriage’s intention to reconcile French Protestants (Huguenots) and Catholics, it triggered one of the worst and bloodiest massacres in French history.

- Thus began the ill-fated career of Margaret of Valois, also known as Queen Margot.

- Six days later (the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre), the Catholic faction assassinated many of the Huguenots gathered in Paris for the wedding. According to Margaret’s memoirs, ‘she saved the lives of several prominent Protestants during the massacre by keeping them in her rooms and refusing to admit the assassins’.

Assassination of Admiral Gaspard de Coligny

- On 22 August 1572, Admiral de Coligny was assassinated. Gaspard de Coligny, born into the powerful Châtillon family, was naturally at the King of France’s service. However, after being imprisoned during the siege of Saint Quentin, he converted to the Reformation and went on to become one of the Protestant party’s military commanders, fighting against the Crown and the Guise.

- The personality of Gaspard de Coligny predisposed him to Calvinism. He was serious and pious, and he imposed strict discipline on himself. He was sensitive to Calvin’s preaching and saw Catholicism’s spiritual deficiencies. The exhortations of his d’Andelot brother and his correspondence with Calvin persuaded him to convert to Protestantism. He only later came out in support of Protestantism.

- Calvinism (also known as the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, or Reformed Christianity) is a major Protestant denomination that adheres to the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice established by John Calvin and other Reformation-era theologians.

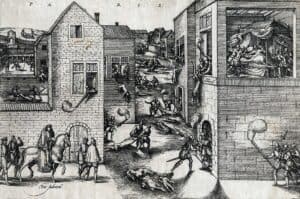

This popular print by Frans Hogenberg depicts Coligny’s attempted assassination on 22 August, and his murder on 24 August, respectively. - He persisted in his support for the Protestant cause. Sir de Maurevert shot at and wounded Coligny on 22 August 1572, at the end of a game of tennis, so that the king had him dragged inside. On the evening of 23 August, the King’s Council began the slaughter of Protestant leaders. Coligny was thrown out a window, cut up and displayed in various locations throughout Paris.

Massacres

Following the slaughter of Admiral Coligny, any Huguenot noblemen were massacred in the Louvre palace or on the streets of Paris. They were caught off guard at night and unable to defend themselves.

The massacre spread throughout Paris

- The massacre raged on for three days in Paris, but the king was powerless to stop it. The level of violence had reached an all-time high. The Catholics, identifiable by the white cross on their hats, attacked all Protestant homes.

- The streets were blood-red. In Paris, the number of victims was estimated to be around 4,000. The king stood up in parliament on 26 August and took credit for the massacre.

The massacre spread to the provinces

- As word spread, violence erupted throughout the provinces, with local St Bartholomew massacres taking place in La Charité, Meaux, Orléans, Lyon and other towns from August to September 1572. At least 10,000 people were killed in the provinces in total.

- Pope Gregory XIII reacted positively to the news, ordering thanksgiving masses and commissioning a special medal to commemorate the occasion.

Key Participants

- During the late 16th century, Margaret of Valois was Queen of France. She was the daughter of France’s King Henry II and the infamous Queen Catherine de’ Medici. Her relationship with her brothers Charles IX and Henry III was strained, and her father married her to Protestant Henry de Bourbon, her distant cousin and King of Navarre.

- Henry, the third son of Henry II and Catherine de’ Medici, was initially titled Duc d’Anjou. During the reign of his brother, Charles IX, he was given command of the royal army against the Huguenots and conquered two Huguenot leaders. Henry narrowly avoided death thanks to his wife’s assistance and his pledge to convert to Catholicism.

- From 1560 until his death in 1574, Charles IX reigned as King of France. During Charles’ reign, decades of conflict between Protestants and Catholics came to a head. Following the massacre of Vassy in 1562, civil and religious war erupted between the two parties. Under the influence of his mother, Catherine de’ Medici, King Charles IX of France ordered the assassination of Huguenot Protestant leaders in Paris, sparking a killing that resulted in the massacre of tens of thousands of Huguenots across France.

- Catherine de’ Medici was not destined to be queen. The ‘Florence orphan’ suffered more losses as a child than most people do in a lifetime. But fate intervened, and the ‘duchessina’, as she became known among Florentines, married into the French royal family. She had no idea she would one day become Queen of France. The origins of the assault on Coligny are unknown. But as a member of the court – the royal family, and the council – Catherine appears to have authorised not the massacre itself, but the death of the admiral and his main followers.

Reactions

- The massacre on St Bartholomew’s Day shocked Protestant Europe. It was an unprecedented event that did not fall within their contexts of reference.

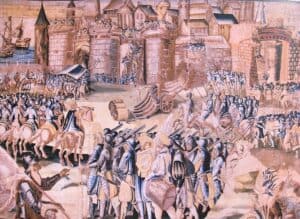

The Siege of La Rochelle (1572–1573) began soon after the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre. - Nonetheless, people in the Netherlands were used to hearing about religious wars – many sources had emphasised the mass killings of the conflict in their neighbouring country. Could one argue that chronicles in the Netherlands were predisposed to expect a massacre because of what happened in France in the 1560s ?

- The news of the massacres quickly spread throughout Europe, with official reactions reflecting the continent’s religious divisions.

- Catholic countries triumphantly celebrated the event. While Pope Gregory and his cardinals ordered the performance of a solemn Te Deum, Philip II reportedly laughed and danced around the room.

- Protestants in Swiss cities and Elizabethan England, on the other hand, were taken aback. Huguenot survivors were either too traumatised to speak or couldn’t remember what had happened.

- There are few testimonies from Catholics who did not take pride in the actions of their co-religionists. Others simply did not want to hear about the carnage.

- It was dangerous to know too much in these chaotic times: some locked themselves in their rooms with their ears taped shut.

- Nonetheless, travellers, Protestant refugees, and Paris correspondents quickly spread word of the massacre throughout the rest of Europe.

- Following the massacre on St Bartholomew’s Day, the French king was eager to control the spread of information and devised a complex strategy to do so.

- First, he dispatched ambassadors to Europe’s major courts, each with a unique story to tell. Catholic rulers were told that the French king wanted to restore religious unity in his kingdom, whereas Protestant rulers were told that the king only wanted to punish a few nobility rebels.

- Moreover, Charles found it important to differentiate between the ‘royal execution’ of Coligny and his lieutenants, and the widely known killings that had followed, and which had risen unexpectedly.

- This official royal version of the massacre’s story was distributed throughout France in the form of a pamphlet.

- It accused Coligny and other Protestant nobles of plotting against their princes and the state.

- In England, the French ambassador gave Elizabeth I a full explanation, denying that the massacre had any connection to religion: the French Huguenot nobles had been executed as defiant subjects.

- In contrast, the Pope was advised that the French king had taken decisive action against religious divisions in his kingdom. In the Netherlands, Catholic diarists accepted the story, being told to appease the Protestant rulers, while Protestants believed in the premeditated murder of religious dissenters.

Conclusion

- The St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre could not have occurred without the sharp religious distinctions that allowed for no compromise. As the ‘new teachings’ spread, the religious unity of the pre-Reformation period was replaced by a constantly repeating paradigm of ‘us’ vs ‘them’.

Catherine de’ Medici is in black. The scene from Dubois re-imagined. - The St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre was not the first time Europeans slaughtered each other in the name of religion, nor would it be the last, but it was the most dramatic and heinous at the time. Following the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, governments realised that they would have to take the religious beliefs of many other nations into careful consideration in their various associations. Not only were thousands of Protestants killed in France, but many more fled the country or converted to Catholicism, reducing the country’s Protestant population significantly.

- The massacre triggered the fourth conflict in the French Wars of Religion, which lasted until 1598, when the Edict of Nantes ended hostilities.

- This edict ended one chapter in Europe’s religious turmoil in the 16th and 17th centuries. But it did not end the conflict, as the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), fuelled by religious differences and regarded as one of the most deleterious wars in European history, would richly demonstrate.

Fast Facts

Event Name: St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre

Description: A three-month-long violent attack by Catholics on the Protestant minority that began in Paris and spread to other French cities.

Start Date: 24 August 1572

End Date: October 1572

Location: Began in Paris and spread throughout France