Download The Long Parliament Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about The Long Parliament to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Aftermath of the First Bishops’ War

- Assembly of the Long Parliament

- Timeline of the Long Parliament (1640-1660)

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about The Long Parliament!

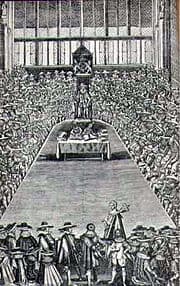

Following the short Parliament that sat for three weeks, Charles I was forced to convene Parliament again as he wanted to pass financial bills as a result of the costs of the Bishops' Wars. Lasting from 1640 until 1660, it was called the Long Parliament and could only be dissolved upon agreement of its members. Highly critical of Personal Rule, it passed several Acts and Ordinances that targeted the king’s prerogative rights. After clashing with the New Model Army in 1648, many of its members were excluded and were only reinstated in 1660. It dissolved itself in February 1660 before the elections for a new Parliament.

Aftermath of the First Bishops’ War

- Under the reign of James VI and I, Scotland and England were united under the same monarch and religion. During this time, much intercountry conflict fell away. However, conflict still remained between locals within the regions. This, once again, came down to Protestant-Catholic conflict. In Scotland, the Lowlands were predominantly Protestant, while the Highlands were predominantly Catholic.

- Fast forward to the reign of James VI and I’s son and heir, Charles I:

- Whilst his father compromised with religious tensions in England and Scotland, Charles I attempted to impose Anglicanism on the Presbyterian Scots.

- This led to the First Bishops’ War in 1639.

Charles I The First Bishops’ War

- What? Charles I wanted bishops to rule the Church, while the Scots wanted a Presbyterian system, where bishops did not rule.

- What happened? The Scots opposed the changes and voted to expel those in favour of the Anglican system. Charles I responded with military force between 1639 and 1640 and the English forces took control of Scotland. Because he had dissolved his Parliament and refused to convene it to gain finance for the campaign, he used his own resources.

- Impact? Charles I was left financially weak.

- Following the First Bishops’ War and the Treaty of Berwick, Charles I’s rule entered a period of financial and diplomatic distress.

- Because of his financial weakness, he was forced to call Parliament for the first time in 11 years.

- Parliament was summoned on 13 April 1640, during which the king asked for a subsidy of £180,000 to raise n 9,000-strong army to deal with future Scottish wars.

- The earls of Northumberland and Strafford, senior advisers to Charles, suggested he forfeit ship money in exchange for £650,000 (the war would actually cost £1 million, or £185 million in today’s money).

- Parliament saw the king’s need for money as an opportune time to pressure him into reforms.

- Member of the Parliament John Pym expressed his refusal of the House of Commons to grant subsidies unless royal abuses were addressed.

- However, it fell on deaf ears and Charles I dissolved Parliament after being in session for only three weeks.

- This became known as the Short Parliament.

Assembly of the Long Parliament

- Still intent on passing financial bills, Charles I issued writs in September 1640, summoning a Parliament to convene on 3 November. He intended it to pass financial bills. When Parliament first met in November, it became clear that its members, in both houses, were almost unanimous in their disapproval of the non-parliamentary policies of the Personal Rule.

- Whilst Parliament was highly critical of Charles I, direct attacks on the monarch were still regarded as unacceptable.

- Instead, the king’s counsellors were targeted, particularly Strafford. Strafford was impeached, arrested and sent to the Tower in November.

- John Finch and Archbishop William Laud were also impeached. Finch fled abroad and Laud joined Strafford in the Tower.

- With many people calling for radical reforms in the Church of England, Parliament was presented with the Root and Branch Petition in December 1640.

- Signed by 15,000 Londoners, it demanded Parliament to abolish episcopacy from the 'roots' and in all its 'branches'.

- It formed the basis of the Root and Branch Bill introduced in Parliament by Henry Vane and Oliver Cromwell in May 1641.

- Meanwhile, Strafford defended himself so well that his opponents were forced to adopt a more drastic measure.

- Pym moved a bill of attainder, declaring Strafford a traitor and condemning him to death without further trial.

- Increasing public pressure led Charles I to sign the death warrant on 10 May. Strafford was beheaded two days later.

Parliament further attacked the king’s prerogative rule:

- The Triennial Act ensured that Parliament met every three years and could not be dissolved without its own consent.

- The prerogative courts were abolished as they were seen as challenging the supremacy of the law.

- The collection of non-parliamentary taxation, such as ship money, was declared unlawful.

Between 1640 and 1641, the Long Parliament tore down the structure of Personal Rule and Charles I had to assent reluctantly to the weakening of his royal power.

Timeline of the Long Parliament (1640-1660)

- The Long Parliament received its name to distinguish it from the Short Parliament. It lasted from 1640 until 1660, when it was finally dissolved by its members in accordance to the Triennial Act.

- The Triennial Act was passed on 15 February 1641.

- Archbishop William Laud was imprisoned on 26 February 1641 whilst Strafford was executed on 12 May 1641.

- The Habeas Corpus Act 1640 was passed in July 1641. It abolished the Star Chamber that was created in the late 15th century.

- Ship money, or tax levied by the Crown on coastal cities and counties for naval defence, was declared illegal in August 1641.

- The Grand Remonstrance, a list of 204 grievances, was presented to Charles I by Parliament in December 1641. It called for the expulsion of all bishops from Parliament, a purge of officials, Parliament having a right of veto over Crown appointments, and an end to sale of land confiscated from Irish rebels. It divided Parliament into the Royalist camp, who supported the king, and the Parliamentarians.

-

Charles I’s attempt to arrest the Five Members of the Commons In January 1642, Charles I ordered the arrest of Edward Montagu, 2nd Earl of Manchester, and Five Members of the Commons, namely Pym, John Hampden, Denzil Holles, Arthur Haselrig and William Strode, on charges of high treason. The members who had been forewarned were able to escape.

- Charles I left London with his family and headed north to York in January 1642. He was accompanied by many Royalist members of the Commons and Lords. This guaranteed his opponents’ majorities in both houses. Parliament then passed the Clergy Act, which excluded bishops from the House of Lords. Charles I approved it since he was already gathering an army and retrieving all such concessions.

- Following the king’s refusal to enact the Militia Bill in March 1642, Parliament decreed that its own Parliamentary Ordinances were valid laws, even without royal assent. This allowed them to pass the Militia Ordinance, which granted them control of the Trained Bands.

- On 1 June 1642, members of the Lords and Commons sent a list known as the Nineteen Propositions to Charles I, who was now in York. The proposal suggested Parliament have a larger share of power, Parliamentary supervision of foreign policy, responsibility for the command of the militia, and making the king’s ministers accountable to Parliament.

- By mid-1642 the Parliamentarians and Royalists began to arm. Charles I gathered troops by issuing Commissions of Array, and Parliament called for volunteers for its militia. After failed negotiations to avert war, in August 1642 the king raised the royal standard, signalling the start of the First English Civil War.

- In 1645, Parliament, determined to fight to the end, passed the Self-denying Ordinance that led to the formation of the New Model Army under the command of Fairfax and Cromwell. This army effectively put the Royalists on the verge of defeat by early 1646. The war ended with victory for the Parliamentarian alliance and Charles I in custody.

- In May 1648, the Second English Civil War ignited. Charles I continued to refuse significant concessions. Whilst Parliament was in favour of negotiating with the king, Cromwell and the New Model Army opposed any further talks. Cromwell was already taking action to consolidate power.

- In December 1648, Pride’s Purge took place, in which the New Model Army under the command of Colonel Thomas Pride forcibly removed anyone who refused to support them. This amounted to about half of the MPs. Those who remained became known as the Rump Parliament.

- The Rump Parliament was responsible for arranging for the trial and execution of Charles I on 30 January 1649 and the setting up of the Commonwealth of England in 1649. However, it was forcibly disbanded by Cromwell when it became a threat to his huge and expensive army. The Barebones Parliament succeeded it, and then the First, Second and Third Protectorate Parliament.

- On 3 September 1658, Oliver Cromwell died. His son, Richard, succeeded him, but did not have the same power base in Parliament. Since he had never served in the army, he lost control of the Major-Generals. Consequently, just eight months later, he was forced to resign and the Protectorate came to a sudden end.

- The Rump Parliament was summoned again and convened on 7 May 1659. After five months in power, it was once again forcibly disbanded due to clashes with the Army. An unelected Committee of Safety briefly ruled until the Rump was again restored in December 1659 with the support of the Navy.

- When General George Monck arrived in London in February 1660 and found the Rump unwilling to cooperate with his plan, he reinstated the excluded members of the Long Parliament to prepare legislation for a new Parliament.

- The Long Parliament dissolved itself on 16 March 1660 before the elections for a new Parliament.

Image Sources

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Long_Parliament

- https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw01221/King-Charles-I?LinkID=mp00840&role=sit&rNo=6

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/89/Attempted_Arrest_of_the_Five_members_by_Charles_West_Cope.jpg/260px-Attempted_Arrest_of_the_Five_members_by_Charles_West_Cope.jpg