Treaty of Tordesillas Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about the Treaty of Tordesillas to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Prior to the Treaty

- Signing and Terms of the Treaty

- Demarcation Line

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about the Treaty of Tordesillas!

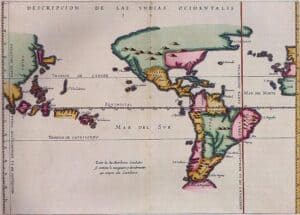

The Treaty of Tordesillas (the present-day Spanish province of Valladolid) was an agreement between Spain and Portugal to divide the so-called New World outside of the European continent into two spheres of influence. Signed on 7 June 1494, this created a demarcation or imaginary line that demonstrates the divide. The vertical line cuts through the Atlantic Ocean, granting the American continent to Spain, while leaving the African west coast and anything beyond the southern tip of the Cape Peninsula, known as the Cape of Good Hope, to Portugal. The treaty made Spain and Portugal global empires.

Prior to the Treaty

- In 1452, a series of papal bulls, official letters released by the pope of the Catholic Church, tried to define the partition of Atlantic territories, which had been a source of conflict between the Spanish and Portuguese empires. At the time, the lands were either newly discovered or had yet to be discovered.

- It was only during the Treaty of Alcáçovas-Toledo in 1479-1480 when the said papal bulls were confirmed and approved, settling navigation and conquest rights in the Atlantic Ocean. So by 1481, through the papal bull Aeterni Regis (“Of the eternal king”), the Castilian kingdom and Canary Islands were granted to Spain. Meanwhile, the Fez kingdom, the islands of Madeira, Porto Santo, Azores, and Cape Verde, and all lands south of the Canary Islands were given to Portugal.

- But the treaty was tested when Italian navigator Christopher Columbus, whose sea voyages were sponsored by Spain, arrived at undiscovered lands in Asia in 1492. These lands became known as the “New World.”

A painting entitled 'Landing of Columbus at the Island of Guanahaní, West Indies' by John Vanderlyn, circa 1846. - Portugal was quick to assert that the newly discovered territories were under the empire’s sphere of influence, citing the papal bulls of 1455, 1456, and 1479. The Spanish monarchs contested the claim, and new papal bulls were released. The new papal letters, issued on 3-4 May 1493 by Pope Alexander VI, a close companion of the Spanish King, highly favoured Spain.

- The papal bull Inter caetera declared that all lands west and south of the Azores or Cape Verde Islands must be granted to the Spanish empire. All land east of the line, by default, should have been given to Portugal. But the papal bulls did not specify which territories should belong to the Portuguese, preventing the empire from claiming any newly discovered areas.

- On 25 September 1493, another papal decree called Dudum siquidem granted Spain all lands in the Indian continent, which was clearly situated east of the line.

Signing and Terms of the Treaty

- Knowing that the papal bulls of Alexander VI highly disadvantaged his empire, especially in terms of expansion efforts in India, Portuguese King John II initiated a negotiation with Spanish monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella. He sought to move the line to the west in order for Portugal to claim new territories east of the line.

- Portugal had only navigated the African eastern coast by 1493. As a result, the Treaty of Tordesillas was signed on 7 June 1494. But the monarchs of the two kingdoms took time before formally ratifying it. Spain upheld the treaty on 2 July 1494. Portugal followed suit on 5 September 1494. The decision granted Spain the lands to the west and Portugal the lands to the east.

An illustration of the division of the non-Christian world between Castile and Portugal - 1494 Tordesillas meridian (purple) and the 1529 Zaragoza antimeridian (green). - Decades later, the other territories were partitioned through the Treaty of Saragossa, formalised on 22 April 1529, which declared the anti-meridian or the 180th meridian to the demarcation line mentioned in the Treaty of Tordesillas. The original copies of both treaties can be found in Spain’s Archivo General de Indias and in Portugal’s Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo.

- Nonetheless, the terms of the Treaty of Tordesillas were vaguely enforced. For instance, when Portugal expanded from Brazil across the meridian, Spain did not complain. When the King of Spain ruled both Spain and Portugal from 1580 to 1640, the treaty was largely ignored. By 1750, it was overtaken by the Treaty of Madrid, leaving already-occupied lands in South America to Portugal, although Spain quickly disputed the new treaty.

- Despite the loose implementation, the treaty managed to identify approximate spheres of influence, particularly in North Africa. Spain conquered the city of Melilla which bordered Morocco and the territories across from the Canary Islands, while Portugal took control of all lands west and south of Melilla.

Demarcation Line

- The line of demarcation declared in the Treaty of Tordesillas did not actually specify the territories the line was supposed to divide. No specific degrees, lengths, or islands were mentioned, other than the fact that the demarcation line stretched from the Cape Verde Islands.

- The treaty said that such matters would be discussed through a joint voyage, which never happened. Specific degrees can be measured through a ratio of marine leagues to degrees which can be used for any sized Earth. Alternatively, it can be determined through specific marine leagues applied to the Earth’s real size.

- In 1495, Jaume Ferrer de Blanes, as requested by the Spanish monarchs, was the first to determine the actual distance of the demarcation line. Ferrer said that the line was 18° west of Fogo, the most central island of the Cape Verde Islands, with a longitude of 24°25’W of Greenwich. Thus, he placed the demarcation line at 42°25’W on his sphere. At the time, Ferrer’s sphere was 21.1 percent larger than the modern sphere.

- A pole-to-pole line known as the southern line that travels through the Cape Verde Islands was depicted on Juan de la Cosa's map from 1500. It was suggested that this might be a representation of the Tordesillas Treaty.

- Meanwhile, Henry Harrisse, who mapped the geographic representations of the so-called New World, stated that the demarcation line, on the modern sphere, was at 42°30’W.

- Following Ferdinand Magellan’s circumnavigation in 1519-1522 and his discovery of the Moluccas, known as the Spice Islands, the demarcation line became hotly contested. This led to the signing of the aforesaid Treaty of Saragossa in 1529.

An illustration of the first circumnavigation of the world by Ferdinand Magellan and Juan Sebastián Elcano which occurred from 1519 to 1522. - To claim the Moluccas, Portugal had to pay 350,000 ducats of gold to Spain. The anti-meridian was also established to prevent Spanish navigators from occupying the Moluccas. The anti-meridian was around 300 leagues or 17° to the east of the Spice Islands, which cut through the Las Velas and Santo Thome islands.

- It must be cleared, however, that the Treaty of Saragossa did not create an equal demarcation line. So the result was that the two unequal hemispheres: Portugal’s part was about 191°, and Spain’s part was about 169°, with a variation of ±4° since the Tordesillas line’s location remained vague.

Image Sources

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Map_of_Meridian_Line_set_under_the_Treaty_of_Tordesillas.jpg

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Landing_of_Columbus_(2).jpg

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Spain_and_Portugal.png

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Magellan_Elcano_Circumnavigation-es.svg