William of Orange Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about William of Orange to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Early Years

- A Journey to Stadtholdership

- A Journey to Become King of England, Ireland and Scotland

- The Reign of William III and Mary II

- William III’s Sole Reign

- Death and Legacy

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about William of Orange!

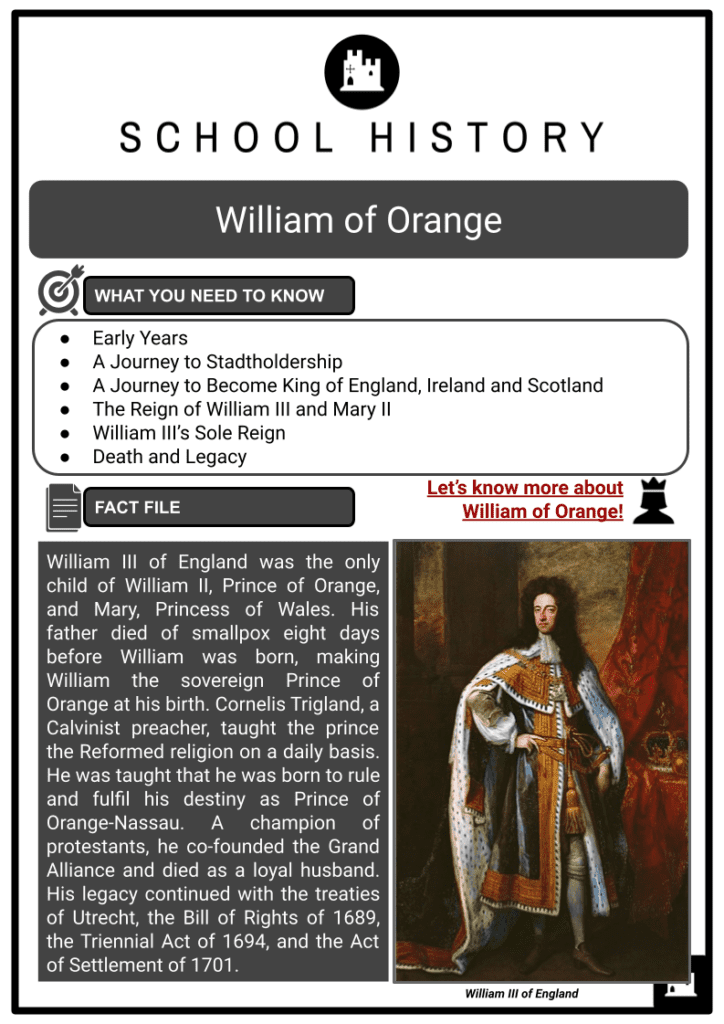

William III of England was the only child of William II, Prince of Orange, and Mary, Princess of Wales. His father died of smallpox eight days before William was born, making William the sovereign Prince of Orange at his birth. Cornelis Trigland, a Calvinist preacher, taught the prince the Reformed religion on a daily basis. He was taught that he was born to rule and fulfil his destiny as Prince of Orange-Nassau. A champion of protestants, he co-founded the Grand Alliance and died as a loyal husband. His legacy continued with the treaties of Utrecht, the Bill of Rights of 1689, the Triennial Act of 1694, and the Act of Settlement of 1701.

Early Years

- On 4 November 1650, William III was born in The Hague, Dutch Republic. He was the only son of William II, Prince of Orange, who from 14 March 1647 until his death three years later served as the stadtholder of the United Provinces of the Netherlands. His mother was King Charles I of England, Scotland and Ireland’s eldest daughter, as well as the sister of King Charles II and King James II and VII.

- At birth, he was the sovereign Prince of Orange due to his father’s death eight days before he was born. William’s mother showed little interest in her son, and kept herself away from Dutch society on purpose. The prince was taught on a daily basis about the Reformed religion by the Calvinist preacher Cornelis Trigland. He was taught that he was destined to rule and fulfil his destiny as the Prince of the House of Orange-Nassau.

Painting showing William II, Prince of Orange, and Mary, Princess Royal - After his mother’s death, the controversy over his guardianship started to spark an issue between his family supporters and the Republicans in the Netherlands. However, the Second Anglo-Dutch War elevated William’s position in the Dutch government, making him a ‘Child of State’ or ward of the government.

- The Second Anglo-Dutch War, also known as the Second Dutch War, was a conflict between England and the Dutch Republic, fought primarily for control of the seas and trade routes, as England sought to end Dutch dominance of world trade during a period of intense European commercial rivalry, but also because of political tensions.

A Journey to Stadtholdership

- Oliver Cromwell and the States General of the United Netherlands made a treaty at Westminster in April 1654 to end the First Anglo-Dutch War. This treaty was accompanied by an act to exclude William III, Prince of Orange, from the office of Stadtholder. This act was known as the Act of Seclusion (1654).

- As William continued to age, the Republicans, led by Johan de Witt and the Orange family supporters, continued to struggle for the stadtholder of William. In 1670, William obtained permission to travel to England to urge Charles II to pay back the debt owed by the House of Stuart to his family (the House of Orange). However, Charles was unable to pay. To appease the situation, Charles II showed William the secret Treaty of Dover between England and France.

- Meanwhile, in January 1672, William wrote a secret letter to Charles, asking his uncle to take advantage of the situation by exerting pressure on the States to appoint William as Stadtholder. In exchange, William would ally the Republic with England and serve Charles’s interests to the extent of his honour and loyalty. However, Charles ignored the proposal and proceeded with his war plans with his French ally.

During the English Civil War, Oliver Cromwell served as Commander-in-Chief of the Parliament of England’s armies against King Charles I. - The Franco-Dutch War and the Third-Anglo-Dutch War crippled public trust in the Republicans of the Netherlands and sought to instill William as Stadtholder.

- Charles II, through a special envoy, met William in Nieuwerbrug and presented Charles’s proposal. This proposal contained William’s surrender to England and France, as well as Charles’s promise to make him Sovereign Prince of Holland rather than Stadtholder. William refused the proposal.

- On 15 August, William published a letter from Charles II, stating that the English king had declared war because of the De Witt faction’s ‘aggression’. This enraged the people. Johann and his brother Cornelius De Witt were brutally murdered by Orangist civil militia on 20 August. William fought on against the English and French invaders, allying himself with Spain and Brandenburg. The Anglo-French fleet was defeated three times by Lieutenant-Admiral Michiel de Ruyter. As a consequence, they forced Charles to end England’s involvement through the Treaty of Westminster of 1674.

A Journey to Become King of England, Ireland and Scotland

- In 1677, William married his cousin Mary II, the eldest daughter of James II (VII of Scotland). Mary’s father did not favour the marriage but was pressured by his brother, King Charles II. William saw that this marriage would leverage the possibility of his succession to Charles’s kingdom. Charles, on the other hand, viewed this as leverage in negotiations relating to war.

- William’s proclamation as King of England leveraged the political status of the Netherlands. Louis XIV of France sought peace with the Dutch Republic. But the conflict with the French was still present. William was weary of Louis XIV’s ambitions of dominance in Europe.

- In 1854, the Southern Netherlands and Germany were reunited, and the Edict of Nantes was rescinded.

- France’s annexations in the Southern Netherlands and Germany and the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 resulted in a surge of Huguenot refugees to the Republic of the Netherlands. As a consequence, William III joined the League of Augsburg in 1686.

- In 1680, Charles II’s reign enacted The Exclusion Bill. This bill declared the exclusion of his brother James II from the throne due to his Catholicism.

- Huguenots were French Protestants who followed the theologian John Calvin’s teachings in the 16th and 17th centuries. Huguenots fled the country in the 17th century after being persecuted by the French Catholic government during a violent period, establishing Huguenot settlements all over Europe, the United States and Africa.

Mary II, Queen of England, Ireland and Scotland - On the other hand, William’s marriage to Mary II placed him in a strong position as a candidate for the English throne if James II (his father-in-law and uncle) would be excluded because of his Catholicism. After James II inherited the throne from Charles II in 1685, William approached him about joining the League of Augsburg.

- In 1687, James II declared unequivocally that he would not join the anti-French alliance. In November, William addressed the English public in an open letter about James’s pro-Catholic and religious tolerance policies. This event stirred the public up and incited English politicians to urge an armed invasion of England.

- In June 1688, Mary of Modena (James II’s wife) gave birth to a son named James Francis Edward Stuart. The birth of an heir would threaten Mary II (William’s wife), who was first in line to the English throne.

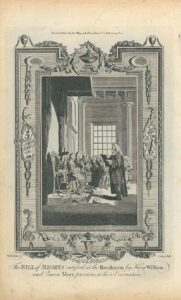

- This also raised the prospect of having a continuing Roman Catholic monarchy. The trial of the seven bishops and the Declaration of Indulgence threatened the Anglican Church. On 30 June 1688, the same day the bishops were acquitted, a group of political figures known as the ‘Immortal Seven’ sent William a formal invitation, informing him that his intentions to invade England were public knowledge. On 5 November 1688, William invaded England. He proclaimed that he would maintain the liberty of England and the Protestant religion.

- William, with his vast army, intimidated James’s supporters. A number of supporters, notably Lord Churchill of Eyemouth, switched sides upon his arrival. James attempted to resist William at first, but realised that his efforts would be futile. James attempted to escape but was captured by William. William permitted James to leave the country for France because he did not want James to be a martyr for the Roman Catholic cause. In 1689, Parliament passed the Bill of Rights. This bill deemed that James had abdicated the government of the realm by attempting to flee, thereby leaving the throne vacant.

- On 11 April 1689, the Bishop of London, Henry Compton, crowned William III and Mary II together at Westminster Abbey. On the same day, Mary and William were offered the Scottish crown. They accepted on 11 May 1689.

The Reign of William III and Mary II

- William lobbied for the Toleration Act of 1689, which guaranteed religious tolerance to Protestant nonconformists. It did not, however, go as far as he wished in terms of religious liberty for Roman Catholics, non-trinitarians, and those of non-Christian faiths.

- The Bill of Rights, one of the most important constitutional documents in English history, was passed in December 1689. The act, which affirmed and acknowledged many clauses of the previous Declaration of Rights, placed restrictions on the prerogative powers.

- It stated that the sovereign could not, among other things, suspend laws passed by Parliament, levy taxes without parliamentary consent, violate the right to petition, raise a standing army during peacetime without parliamentary consent, deny Protestant subjects the right to bear arms, interfere excessively with parliamentary elections, punish members of either House of Parliament for anything said during debates, impose excessive bail, or inflict cruel and unusual punishment.

- Although the majority of the English recognised William and Mary as sovereigns, a substantial minority refused to recognise their claim to the throne. Instead, they believed in the divine right of kings. Over the next 57 years, Jacobites pushed for James and his heirs’ restoration.

- William’s reputation in Scotland suffered further damage when he refused English aid to the Darien scheme, a Scottish colony that failed miserably (1698–1700).

- Parliamentary factions were present in William III’s reign. William favoured the Whig faction because he needed to continue funding his war against France. The Whig faction was responsible for the establishment of the Bank of England. His decision to grant a Royal Charter to the Bank of England was seen as his most important economic legacy. It laid the financial groundwork for the English takeover of the Dutch Republic and the Bank of Amsterdam’s central role in global commerce in the 18th century.

- William’s involvement in the Nine Years’ War against France caused his absence from England. While William was away fighting, his wife, Mary II, ruled the realm but followed his advice.

- The 1695 Siege of Namur, also known as the Second Siege of Namur, occurred between 2 July and 4 September 1695 during the Nine Years’ War. Its capture by the French in 1692 and recapture by the Grand Alliance in 1695 are widely regarded as pivotal events in the war. The second siege is widely regarded as William III’s most significant military success.

- The League of Augsburg, the alliance which William joined against France, became the Grand Alliance. The Grand Alliance fared poorly in the battle against France. Mary II died of smallpox on 28 December 1694, leaving William III to rule alone. William was devastated by his wife’s death. Even after he converted to Anglicanism, William’s fame in England fell during his single reign.

William III’s Sole Reign

- In line with the Treaty of Rijswijk, the Nine Years’ War between William III and Louis XIV of France ended. Louis XIV of France recognised William III as the King of England. He accepted that he would not give further assistance to his cousin, James II.

- However, the succession of the Spanish throne alarmed William III because the king of Spain, Charles II, was invalid and had no heir. William feared that the succession of the Spanish throne would shake the balance of power in Europe because the king’s closest relatives were Louis XIV of France and King Leopold I of the Holy Roman Empire.

Charles II of Spain - To resolve this tension, William III and Louis XIV signed the First Partition Treaty that concluded that Joseph Ferdinand of Bavaria, son of Maximilian II Emanuel, Elector of Bavaria, and Maria Antonia of Austria, daughter of Leopold I, would inherit the Spanish throne.

- This tension continued when Joseph Ferdinand died of smallpox in 1699. There was an attempt to amend based on the Second Partition treaty, but in the end Louis XIV ignored the partition when Charles II of Spain granted it to Philip V, grandson of Louis XIV, when he inherited the Spanish throne. Louis also supported the succession of James Francis Stuart, son of the former king of England, James II.

- Conflict with the throne continued to exist as William III failed to produce an heir with his late wife, Mary II. The passage of the Act of Settlement in 1701 prevented the inheritance of James II’s line on the English throne. The English throne succession pointed to Anne, Mary II’s sister, to William’s future marriage, and finally to Sophia of Hanover.

An 18th-century engraving based on a drawing by Samuel Wale of the Bill of Rights being presented to William III and Mary II

Death and Legacy

- The famous British statesman Winston Churchill once said that the fall of William III into a mole’s burrow ‘opened the door to a troop of lurking foes.’ His fall was thought to have been planned by the Jacobites, and this event broke William’s collarbone. William died of pneumonia in 1702.

- William remains the only member of the Dutch House of Orange, to, by any account, have ruled England. His legacy highlights his opposition to the domination of France in the European region.

- William’s reign outcome resulted in the end of the conflict between Parliament and the English monarch since the reign of James I in 1603. The conflict between these opposing forces led to the English Civil War and the Glorious Revolution in England. Conjecture about the conflict led to the passage of the Bill of Rights in 1689, the Triennial Act in 1694, and the Act of Settlement in 1701.

- The passage of these bills cemented the power of Parliament over the monarchs. These bills allow the people to uphold basic civil rights, seek the consent of the people, limit the power of the monarch, and clarify who will be the next to inherit the throne.

Image Sources

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_III_of_England

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oliver_Cromwell#/media/File:Oliver_Cromwell_by_Samuel_Cooper.jpg

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_II_of_England#:~:text=Mary%20II%20(30%20April%201662,his%20first%20wife%20Anne%20Hyde.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_II_of_Spain#/media/File:King_Charles_II_of_Spain_by_John_Closterman.jpg

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bill_of_Rights_1689#/media/File:Samuel_Wale,_The_Bill_of_Rights_Ratified_at_the_Revolution_by_King_William,_