Download Women and Medicine Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Women and Medicine to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Table of Contents

Add a header to begin generating the table of contents

Summary

- Ancient Medicine

- Medieval Medicine

- Early Modern to Modern Medicine

- Notable women in medicine

- Notable women’s medical schools and hospitals

- Other influential women in medicine

- Women in medicine today

Key Facts And Information

Let’s know more about Women in Medicine!

- Since antiquity, women have practised medicine. From herbal remedies to midwifery, women played their natural role as caregivers in ancient times. With the professionalisation of modern medicine and the dominance of men in the field, remarkable women introduced practices that innovated the medical world.

- In British history, women were only allowed to attend medical schools in the late 19th century. Women pioneers in medicine included Elizabeth Blackwell, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and Florence Nightingale.

Ancient Medicine

- In many traditional societies, women served as caregivers, particularly in childbirth. It was not until recent times that men started assisting in childbirth. At the time, ‘wise women’ or even ‘witches’ were skilled in healing.

- The story of Agnodice is said to be the origin of women in Western medicine. Agnodice or Agnodike was a well-constructed myth about the first female physician in ancient Athens.

- In his Fabulae, Roman Gaius Julius Hyginus mentioned that Agnodice, disguised as a man, studied medicine under Herophilus, and secretly worked as a physician in Athens.

- Due to her popularity, rival physicians accused her of seducing women in Athens. Agnodice was tried and her true identity was revealed. As a result, she was charged as a fraud physician. However, the women of Athens argued that she used effective treatments. Agnodice was acquitted, and Athens revoked its law against women in medicine.

- One of the earliest records of women in Western medicine was a Greek physician named Metrodora. She was known to be the author of the oldest medical text written by a woman, On the Diseases and Cures of Women.

- Influenced by the works of Hippocrates, Metrodora’s writings covered gynaecology, hysteria and other areas. The treaties did not cover obstetrics or surgery.

- In contrast to Metrodora, Aspasia, the Physician of Athens, included obstetrics and gynaecology. Highly influenced by Byzantine surgeons and physicians, Aspasia included surgical techniques for varicoceles, hemorrhoids and hydroceles in her writings. She also practised preventive medicine for pregnant women and a birthing technique to ease delivery.

- Merit-Ptah served as the first female chief physician of a pharaoh’s court around 2700 BCE in ancient Egypt. Another female physician named Peseshet also served as ‘lady overseer of female physicians’ in around 2500 BCE.

- Evidence suggests the existence of a medical school at the Temple of Neith in Lower Egypt that a woman ran in 3000 BCE.

- Despite the lack of official records, it was believed that Queens Hatshepsut, Tiye and Nefertiti encouraged women to pursue medicine. However, evidence suggests that most women in medicine served as wet nurses and midwives.

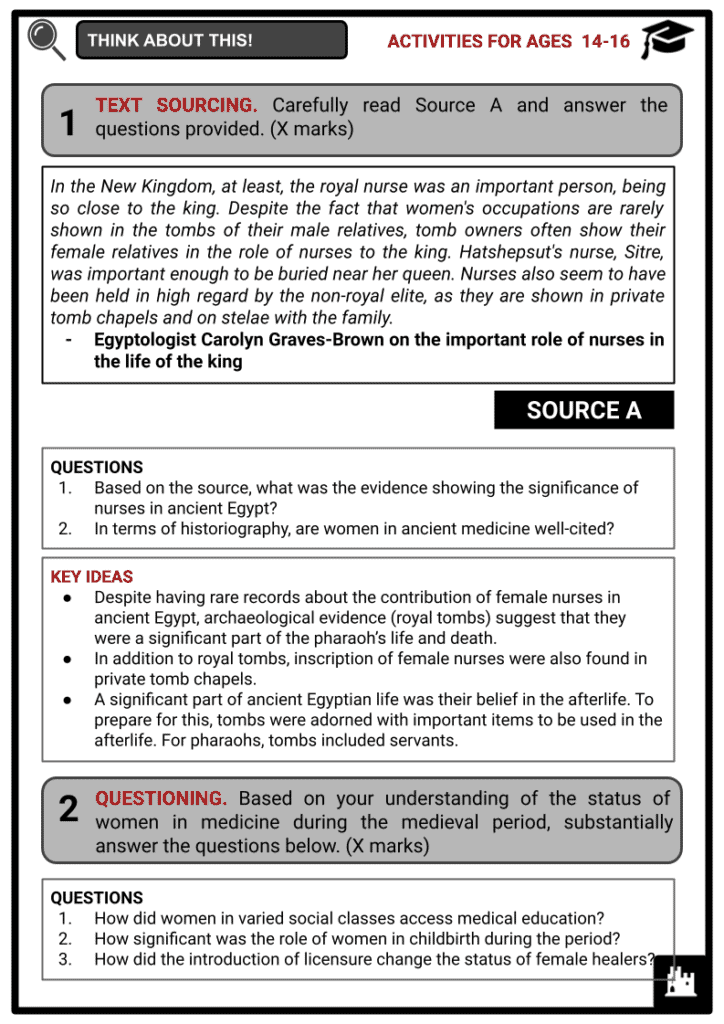

Medieval Medicine

- During the medieval period, women were educated in convents. Many served as herbalists, midwives, nurses and barber-surgeons. Between the 13th and 15th centuries, 24 women were described as ‘surgeons’ in Naples, Italy, and there were another 15 female medical practitioners in Frankfurt, Germany. In rural areas, women practised healing arts and midwifery.

- In the 13th century, universities for medicine were established but excluded women from advanced medical education. Furthermore, when the healing field required clerical vows, which excluded women, male physicians dominated the field.

- A nun and a healer, Hilgard produced scientific-medical texts, including the Liber simplices medicine and the Liber Compositae medicinae.

- Due to women’s ineligibility, many practising healers were accused of being ‘witches’ by clerical and civil authorities.

- During the medieval period, guilds became common among barber-surgeons who skipped getting licensed.

- It was a typical practice for barber-surgeons to allow their wives and daughters to be members of their guilds. In 1286, records showed that Katherine la surgeine of London was a member of a guild. She was the daughter of Thomas the surgeon and sister of William the surgeon.

- In the medieval period, about one-third of female medical practitioners were midwives. At the time, midwives, who were only women, assisted women through childbirth.

- In 1390, Italian physician Dorotea Bucca was the chair of philosophy and medicine at the University of Bologna, a position she held for over 40 years.

- Only a few records showed the need for female assistance in the Islamic world. Male medical practitioners typically called for female help when treating female patients, particularly if the procedure required touching the genitalia. In such cases, male practitioners were required to look for a female practitioner or a eunuch physician.

- Similar to the West, childbirth was taken care of by midwives.

- In ancient Chinese tradition, women were forbidden from getting an education. During the Ming Dynasty in China, Tan Yunxian became known as one of the few women to practise medicine.

- Tan Yunxian was born into a family of doctors. Her grandparents tutored her to learn Chinese medicine. At the time, male medical practitioners were prohibited from touching female patients. This limitation led Tan Yunxian to treat female-related disorders such as menstrual irregularities, miscarriages, barrenness and postpartum fatigue.

- At the age of 50, Tan Yunxian wrote The Sayings of a Female Doctor, including 31 in-depth case studies of her female patients. Amongst her prescriptions were herbal medication and moxibustion.

Early Modern to Modern Medicine

- During the reign of Henry VIII, the specialisation of the healthcare profession began when the king granted a charter to the Company of Barber-Surgeons. However, women were prohibited from this profession.

- In the 16th century, while male physicians were trained in universities, the training of midwives faced criticism. Those who were not licensed were accused of practising witchcraft. Many were labelled as ‘witch-healers’. Midwifery schools opened in Spain, Italy and Holland despite the backlash.

- In the 18th century, King Louis XV of France commissioned Angelique du Coudray to train men and women with proper childbirth care.

Notable women in Medicine

- Martha Ballard (1735-1812) was an American healer and midwife. Between 1785 and 1812, Ballard kept a diary that contained 812 entries of childbirth records. Without formal medical training, she used herbs to treat illnesses such as coughs and aching limbs.

- Elizabeth Blackwell (1821-1910) was the first female British physician recorded in the Medical Register of the General Medical Council.

- Educated in a medical school in the US, Blackwell founded the New York Infirmary for Women and Children. Her achievement broke the ‘glass ceiling’ that women in medicine faced. At the hospital, Blackwell hired women as physicians and faculty.

- During the American Civil War, she aided in nursing efforts for the Union Army. However, her efforts faced resistance from the male-dominated United States Sanitary Commission. In response, Elizabeth and her sister organised the Woman’s Central Relief Association, or WCRA.

- In 1874, Blackwell established the London School of Medicine for Women.

- Elizabeth Garrett Anderson (1836-1917) was the first English woman to qualify as a physician and surgeon in Britain.

- Garrett struggled to obtain a licence in 1865. From serving as a surgical nurse, she battled to be eligible by studying with private tutors. In 1865, Garrett was the first woman in Britain to pass the Society of Apothecaries exam and practise medicine. After acing the exam, the Society of Apothecaries amended its regulations prohibiting privately tutored women from participating.

- In 1876, the Medical Act allowed British medical authorities to license qualified applicants regardless of their sex.

- Despite her licence, Garrett was refused a medical post in hospitals. To practise her education, Garrett opened her clinic at Upper Berkeley Street in late 1865. The following year, she opened the St Mary’s Dispensary for Women and Children at Seymour Place. In 1870, Garrett obtained a medical degree at the University of Sorbonne in Paris.

- By 1873, Garrett became a member of the British Medical Association. Aside from her influential contributions to medicine, Garrett was also an active suffragist.

- Sophia Jex-Blake (1840-1912) was an English physician, feminist, teacher and the first practising female doctor in Scotland. She founded some of the first medical schools for women, one in London and one in Edinburgh. After several hardships to enter medical school, she was admitted to the University of Edinburgh in 1869. It was the first university in Britain to admit women at the time.

- Florence Nightingale (1820-1910), nicknamed the Lady with the Lamp, was an English social reformer, statistician and founder of modern nursing. Her observations at Scutari Hospital in Turkey during the Crimean War gave way to reforms in patient care and hospitals both in Great Britain and, before long, all around the world. After the war, Nightingale’s statistical work and books laid the foundations for professional nursing in Great Britain.

- Marie Curie (1867-1934) was a Polish and naturalised-French physicist and chemist who conducted research regarding radioactivity, which made her known as the ‘Mother of Physics’. She was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize and the first and only woman to win it twice (she won both the 1903 Nobel Prize for Physics and the 1911 Nobel Prize for Chemistry). Curie was also the first woman to become a professor at the University of Paris (in 1906) and the first woman awarded a PhD in research science in Europe.

Notable Women’s Medical Schools and Hospitals

- When women were prohibited from attending medical schools, they sought to establish their own. Below are some of the most historical women’s medical schools.

- Boston Female Medical College founded in 1848 (New England Female Medical College)

- Female Medical College of Pennsylvania founded in 1850 (Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania

- London School of Medicine for Women founded in 1874

- Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women founded in 1886

- Female Medical University founded in 1897 (First Pavlov State Medical University of St Petersburg)

- Woman’s Hospital of Philadelphia founded in 1861

- New England Hospital for Women and Children founded in 1862

- New Hospital for Women founded in the 1870s

- South London Hospital for Women and Children founded in 1912

Other Influential Women in Medicine

- Marie Durocher (1809-1893) was the first female doctor in the Americas.

- Rebecca Lee crumpler (1831-1895) was the first African-American female physician in the US.

- Lucy Hobbs Taylor (1833-1910) was the first female dentist in the US.

- Madeleine Bres (1839-1925) was the first female medical doctor in France.

- France Hoggan (1843-1927) was the first female doctor in Wales.

- In 1947, Gerty Cori (1896-1957) became the first woman to win a Nobel Prize for her works in medicine and physiology.

- Virginia Apgar (1909-1974) became famous for her invention of the Apgar score. It was a test administered to newborn babies. Apgar was also the first woman to acquire a full professor rank at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons.

- Rosalind Franklin (1920-1958) was known for her contributions to the understanding of DNA structure (double helix) through X-ray photographs.

- Clara Barton (1821-1912) was an independent nurse during the Civil War and founder of the American Red Cross.

- Francoise Barre-Sinoussi (1947-) is regarded for her discovery of HIV as the cause of AIDS in 2008.

- Patricia S Goldman-Rakic (1937-2003) was a pioneer of brain research and memory functions. Her studies led to the understanding of schizophrenia, Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s.

Women in Medicine Today

- From 25 female doctors in England and Wales in 1881, the number increased to 495 in 1911. Following the Education Act of 1918 and the Sex Disqualification Act of 1919, women had greater access to medical education.

- When the First World War broke out in 1914, labour shortages in varied fields, including medicine, were filled by women on the home front. By 1915, a few London hospitals began to train women. Until 1944, medical schools only accepted a ‘reasonable’ proportion of women.

- Despite women’s significant contributions during the Second World War, women in the workplace still had restrictions. For example, married or pregnant women were not allowed to work under the marriage bars.

- In the 1960s, the need for more British trained doctors increased the number of accepted female doctors. By the 1970s, the application system for medical school was standardised and based on exam results rather than quota and gender. As a result, more women were encouraged to attend medical schools.

- According to the NHS Information Centre and Health and Social Care Information in 2013, women account for over half of the medical workforce in the UK.

- According to the World Health Organization, in the early 2000s about 40% of physicians in Europe were women. In 2002, about 37% of physicians in England were female.

- In 2017, about 90% of the nursing profession in the UK were women.

- In 2020, out of 300,000 registered doctors in the UK, 140,509 were women.