Chartism Worksheets

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Chartism to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Summary

- Chartism Movement

- Causes of Chartism

- People’s Charter of 1838

- Chartist Leaders

- Three National Petition

Key Facts And Information

Let’s find out more about Chartism!

Chartism was the first most significant national British movement from 1838 to 1848, led by the working class calling for democracy and to expand their voting privileges. It grew due to political disappointments, economic difficulties, and the failure of the 1832 Reform Act, which only granted voting rights to property owners.

The movement tried to unite its supporters and intimidate its opponents by showing how strong public opinion was at mass meetings and through petitions to Parliament.

Causes of Chartism

The principles presented in Chartism had been the core of radical demands for so many years. In fact, the British working classes had been battling for their rights as a reaction to societal and economic issues ever since the 1770s, but their voices weren’t heard.

Reform Act 1832

- The origin of the movement can be attributed to the Representation of the People Act in 1832, most commonly known as ‘Reform Act 1832’ or ‘Great Reform Act’.

- Qualifications were lowered to allow many smaller property owners to vote for the first time. It included the extension of suffrage to small landowners, tenant farmers, shopkeepers, and those who paid a rent of over £10.

Image depicting commemoration of the passing of the act - The act increased the percentage of eligible voters in England, Wales and Scotland. However, it still failed to extend the right to vote to those who did not possess property.

- Since working class leaders had campaigned alongside the middle class for a broader franchise, they felt betrayed by the outcome, which deliberately excluded working class men from voting.

Poverty, Exclusion & Injustice

- Britain entered a period of depression in the late 1830s, with the working classes suffering the most.

- In addition to often horrible factory conditions, they faced the possibility of unemployment and the scarce poor relief. The electoral system only included the richest and were open to corruption.

John Collins, a spokesman for the Birmingham Political Union during a time of tremendous political crisis, canvassed a street in Birmingham to determine how much the working classes’ comforts had improved. He found only one family living in reasonable comfort. The majority of them were unemployed and in terrible shape.

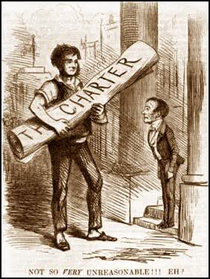

The Corn Law

- The Corn Law that was imposed from 1815-1846 to protect the British farmers from foreign imports of grain kept corn, wheat and bread prices at a high level.

- The lower classes saw living expenses increase and had far less disposable income. The majority of the population had no authority over government taxes and spending, no voice over the price of bread, and no part in industry profits.

Image depicting the outcome of the Corn Law - The Chartist movement believed that by gaining the right to vote, they would be able to elect Members of Parliament who truly represented working men and their interests and who would seek to remove the Corn Law and other legislation that favoured the wealthy at the expense of the poor.

The Napoleonic War and the blockade Britain imposed to prevent foreign goods from entering put British farmers and landowners in a highly favourable position in terms of the high price of home-grown cereals. These landowners were determined to prevent the price of corn and other cereals from dropping. They leveraged their position in Parliament and their right to vote to pass the ‘Corn Laws’.

The Poor Law

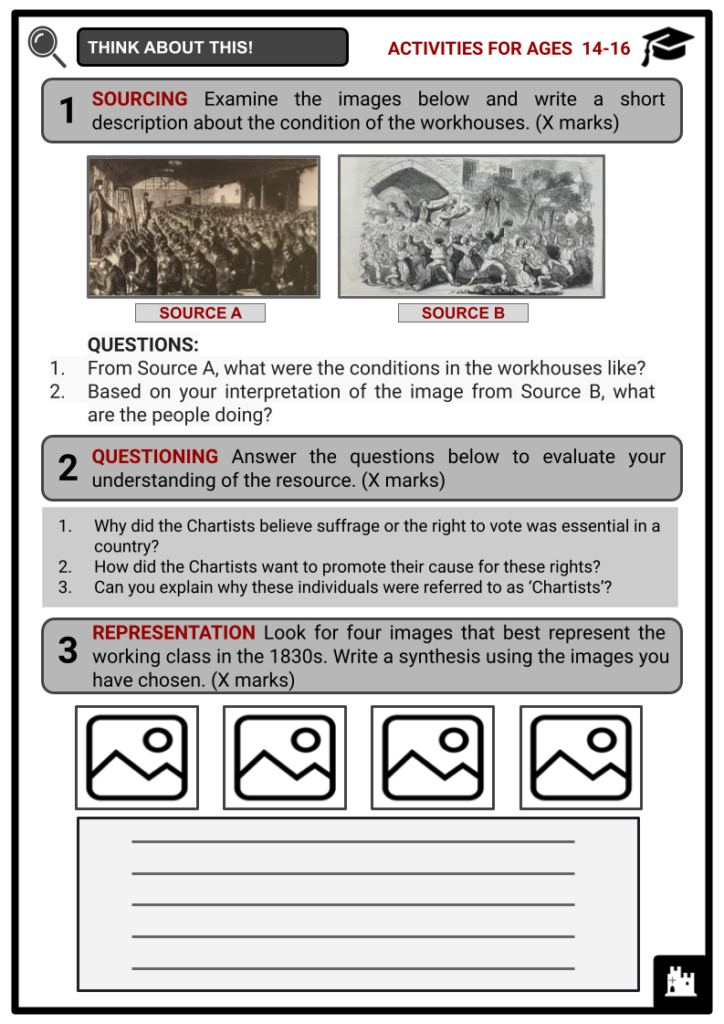

- The actions of the Whig government appeared to exclude and fuel the flames of the disenfranchised, especially after the 1834 Poor Law Amendment, which took away assistance for the working class and forced the poor into workhouses.

- The paupers believed they were treated much worse than slaves with terrible conditions, long hours, forced child labour, malnutrition and neglect.

The Poor Law - A law developed in 16th-century England that provides relief for the poor, sick and aged and provides allowances to workers who earned less than what was considered a subsistence level. Because of this, spending on public aid went up so much that in 1834, a new Poor Law was passed. It was based on a harsh principle that saw being poor among able-bodied workers as a moral flaw. The new law supplied no relief for the able-bodied poor other than workhouse employment, intending to encourage workers to seek employment rather than charity.

People’s Charter of 1838

- As opposition grew in the late 1830s, Chartism as a movement began to emerge as the need for universal male suffrage was seen as necessary to initiate change.

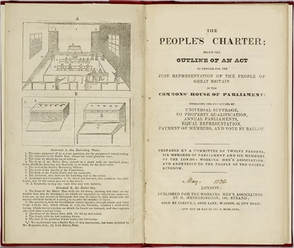

- In May 1838, radical William Lovett of the London Working Men’s Club drafted a charter of political objectives outlining six main demands known as the People’s Charter, which gave its name to the Chartist movement.

- It rapidly gathered support from industrial workers in the north of England, Wales and Scotland.

The People’s Charter - Published by the London Working Men’s Association - The Six Points

- Universal Suffrage - A vote for every man over 21 years of age, unconvicted of crime and of sound mind, in the election of the representatives

- Vote by Ballot - A secret ballot to protect the elector by preventing threat, bribery and influencing a man to vote against his own will or judgement

- Members of the Parliament do not have to own property

- Payment of Members of Parliament

- Equal voting constituencies - The country should be split into equal electoral districts, each with an equal number of people and one representative in Parliament

- Annual Parliaments

- In 1838, a series of large-scale gatherings were held in Birmingham, Glasgow and the north of England to establish the Chartism movement, and the Chartist message rapidly spread across the country.

- The Charter became one of the most famous political manifestos of 19th-century Britain despite the fact that none of these demands were original.

- It was supported by travelling orators and the radical press, particularly The Northern Star, which was created in 1837 by the future Chartist leader Feargus O’Connor.

Chartist Leaders

- Many factors held such a diverse movement as Chartism together, giving what often appeared to be highly localised activity a national structure and goal.

- The movement had several leaders who spoke at massive open-air gatherings across the nation, spreading the Chartist message and building support for the movement.

William Lovett

William Lovett

- A self-educated man in economics and politics and a cabinet maker who formed the London Working Men’s Association.

- Lovett’s moderation made it challenging for him to collaborate with the more militant Chartist leader Feargus O’Connor, hence, his position was limited in Chartism.

- He was arrested following Chartist protests in Birmingham while the convention was in progress and convicted to one year in Warwick jail.

John Collins

- He was the first member of the working class to be elected to the Birmingham Political Union council representing the middle class.

- In the early years of the movement, he was significantly responsible for bringing together English and Scottish radical forces through his speaking tour as a prominent Union orator.

Thomas Attwood

- His Birmingham Political Union offered significant support and supplied Chartism’s core tactic of a national petition.

- He claimed victory for the 1832 Reform Act, which expanded the vote to the middle class.

- He became the first representative for Birmingham, England and his solution for the problems of the working class was currency reform.

Feargus O’Connor

- The owner of The Northern Star.

- He was very well known as the leader of the Chartist movement due to his fierce oratory and platform antics.

- In 1837, O’Connor's newspaper, The Northern Star, was first published. It sold 50,000 copies per week at its peak in 1839. It provided propaganda and unity to the growing movement, which gathered in a series of mass meetings held between May and September 1838 in Glasgow, Birmingham, Manchester and other cities.

- It was known that O’Connor had ties to radical groups that supported reform by whatever means necessary, including violence.

Francis Place

- He was a radical British reformer known for his successful campaign for the repeal in 1824 of the anti-union Combination Acts.

- He was a journeyman tailor and his shop in London became a gathering spot for radicals of like mind.

- He assisted William Lovett in drafting The People’s Charter.

Henry Hetherington

- Hetherington used his newspapers to advocate for the right of the working people to vote.

- He believed that newspaper and pamphlet publication was crucial to the political education of the working class people.

- Hetherington published several radical publications in the 1830s, including The Penny Papers (1830), The Radical (1831) and The Poor Man’s Guardian (1833).

John Frost

- Frost was involved in militant Chartist activities and was the leader of the Newport rising on 4 November 1839, in which soldiers killed about 20 Chartists.

- He was convicted of high treason on 16 January 1840, where he received a death sentence, which was reduced to lifelong exile in Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania).

- William Lovett, Thomas Attwood, Henry Hetherington and Francis Place favoured promoting moderate reforms through peaceful methods, whilst Feargus O’Connor, Bronterre O'Brien and Julian Harney, among others, appeared to encourage more aggressive tactics.

- Regional and craft distinctions and personality conflicts among its leaders hampered the movement from the beginning.

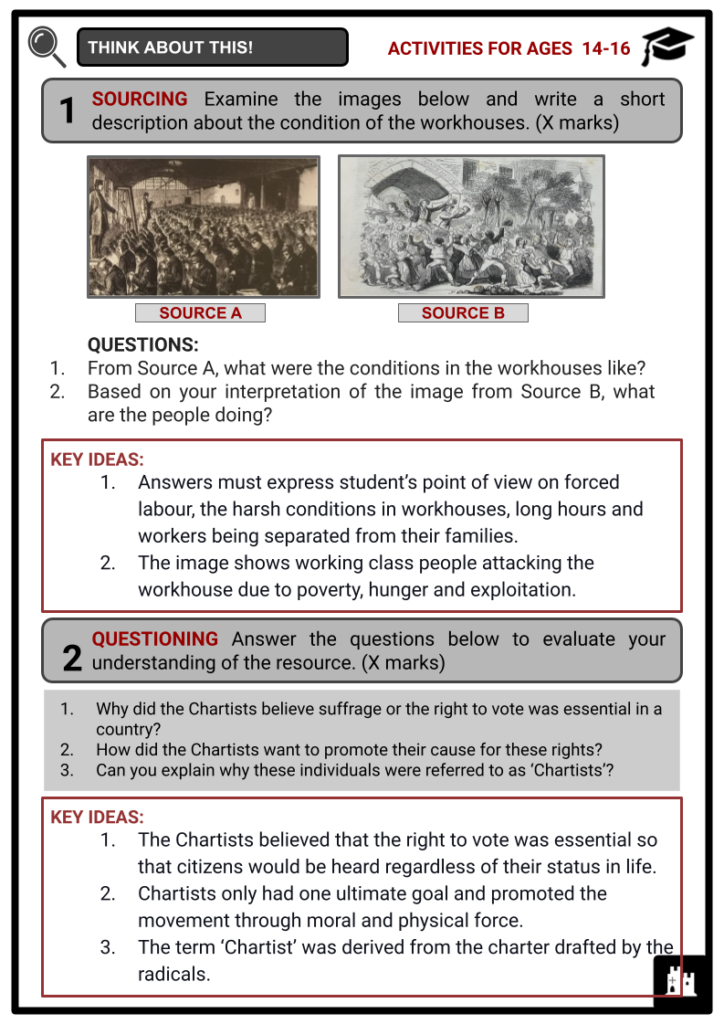

Moral Force

- Chartists such as William Lovett believed that organising public meetings, distributing pamphlets and newspapers, and submitting petitions to the government would persuade those in authority to reform the electoral system.

- However, many people believed that election reform could not be achieved only through applying ‘moral force’.

- Nevertheless, his moderate approach in demanding political reform through a peaceful method gained him the respect of local community leaders.

Physical Force

- All members agreed on the ultimate aim of Chartism, but there were significant disagreements over the means to attain it. ‘Physical force' Chartists, such as Feargus O’Connor, urged the use of violence if the six points of the Charter were not granted through peaceful means.

- Under his forceful leadership, the campaign attained national significance.

- National and local chartists were incarcerated in an effort to destabilise the movement whenever Chartism became threatening in 1838, 1842 and 1848

- Some were imprisoned under severe conditions, including Feargus O’Connor and 58 other Chartist leaders and trade unionists tried in Lancaster after the 1842 national strike.

- Others were sent to Australia and some inmates died in prison due to the harsh conditions.

- Following the introduction of the People’s Charter, the movement organised a National Convention in London, mirroring the structure of Parliament by referring to the delegates as Member of Convention.

Three National Petition

Chartism’s focal points were massive petitioning campaigns in 1839, 1842 and 1848.

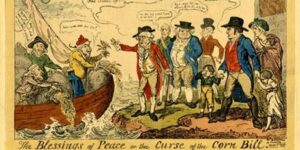

The First Petition in 1839

- On 4 February 1839, a general convention was held to discuss the petition. The primary function of the meeting was to prepare and deliver the National Petition to Parliament. In June 1839, the Chartists presented the petition to the House of Commons signed by 1.3 million working people.

- The majority of the Members of the Parliament strongly rejected the petition.

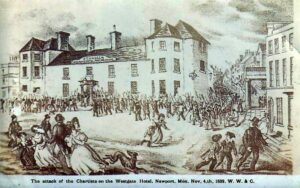

Image depicting the Newport Uprising of 1839 - The dismissal of the petition provoked an uprising led by John Frost, resulting in outbreaks of violence and many arrests in Westgate Hotel, Newport, which took place on 4 November 1839.

- The Chartists were swiftly crushed by armed soldiers waiting at the hotel and were forced to retreat.

- The principal leaders were banished to Australia, and nearly every other Chartist leader was arrested and sentenced to a short prison term.

The Second Petition in 1842

- In early May 1842, the Chartists presented the second petition, known as the greatest Chartist petition, with over three million signatures, to the House of Commons. However, Parliament still did not yield to the Chartists’ demands.

- The rejection occurred during a period of severe economic depression in 1842. So, inevitably, outbreaks of violence and waves of strikes unfolded in response to wage reductions imposed by employers.

- The strike prompted the government to request the assistance of the military to suppress the outrage of the people.

- Its second failure and the economic recovery after 1842 hit Chartism hard. The Chartists decided to pursue other alternatives, such as launching a National Land Company to purchase shares and land, but it was forced to close due to financial instability.

- The Northern Star commented on the injustice of the rulers falling on deaf ears to the 3 million people who signed the petition.

- The Northern Star, owned by Feargus O’Connor, was the best-selling provincial newspaper in Britain, with a circulation of 50,000. It was often bought by groups of Chartists and read aloud, prompting much political discussion and debate.

- It became the official publication of the Chartist movement. It supplied the movement with a vital source of communication, national unity, and continuity and aided O’Connor’s ascent to the top of the Chartist leadership.

The Third Petition in 1848

- The poor harvests beginning in 1846 and an economic crisis in 1847 resulted in the last major surge of Chartism in 1848. The gathering of signatures for a third petition began when meetings resumed.

- A huge meeting was held at Kennington Common in South London on 10 April 1848, followed by a procession to Westminster to present the People’s Charter to the House of Commons.

- There was a large police and military involvement, but the meeting was peaceful, with a crowd estimated at 150,000.

- With nearly six million signatures, the petition was reportedly claimed to be the largest one. However, Parliament examined the petition and found that some signatures were fake and duplicated and rejected it. The petition was defeated heavily again.

Chartism Legacy

- After 1848, the Chartists had exhausted every method available, including petitions, strikes, economic boycotts, and revolution, but with little success.

- Chartism was a popular 19th-century working class movement, despite the fact that it failed to achieve its objectives. Chartism encompassed much more than the People’s Charter.

- It increased awareness and stirred up a large number of working men and women, enabling them to declare their right to be treated as equal citizens.

- It also gave people a chance to learn how to organise and speak in public.

- Moreover, even though the Charter was not enacted, the movement had a huge political impact, immediately placing the ‘Condition of England Question’ on the 1840s political agenda.

- During the lifetime of the Chartist movement, they could not secure the vote for all working men, although its victory took longer than the Chartists had anticipated: five of the six goals of the Chartists had been granted by 1918; only the demand for annual parliamentary elections remained unfulfilled.

- Chartism also contributed to developing a lasting political culture in which later left-wing ideologies might flourish.

- Thomas Carlyle came up with the phrase ‘Condition of England Question’ in 1839 to describe the position of the English working class during the Industrial Revolution.

- He voiced his sympathy for England’s poor and industrial class and called for more deep transformation.

Image Sources

- https://www.londonremembers.com/subjects/chartists

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reform_Act_1832#/media/File:Detail_House_of_Commons.JPG

- https://committees.parliament.uk/committee/326/petitions-committee/news/99040/petitions-and-the-corn-laws/

- https://www.chartistcollins.com/peoples-charter-text.html

- https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/Chartist-Movement/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Newport_Rising